Eduardo Sacheri: ‘In the Argentina of 1975 different sectors saw violence as a very legitimate tool’

In his latest novel, the Argentine writer delves into the turbulent years before the last coup d’état

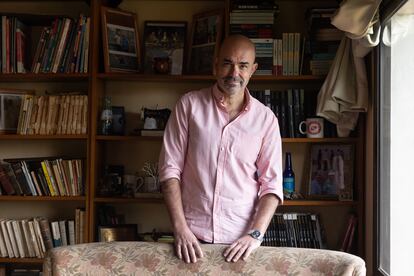

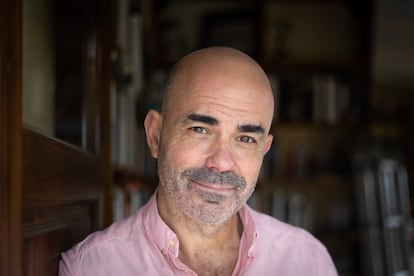

One day in 1974, the phone rang at the Sacheri family home, in the western suburbs of Buenos Aires. Eduardo Sacheri (Castelar, 1967) was six years old when he saw his father answer and then collapse in the kitchen. “Seeing him devastated, crying, not understanding what had happened, was an overwhelming image for me,” says the writer during an interview with EL PAÍS held at his home. On the living room table is a copy of Nosotros dos en la tormenta (Us two in the storm, no English translation yet), his latest novel, dedicated to his father and to that one time he saw him cry. “I think that what one writes, just as it has rational motors, it also has emotional motors. And without a doubt, looking into in that period was a way for me to try to understand those tears,” he admits.

Through that call, the political violence suffered in Argentina of the early 1970s, still in democracy, reached a young Eduardo who dreamed of being a player for the Independiente soccer club. At 55, he is still passionate about his team (he even took part in the collection organized by the influencer Santiago Maratea to save it from bankruptcy), but he succeeded with the pen instead of the ball.

His literary debut, The Secret in Their Eyes, was made into a film by Juan José Campanella. Argentina won its second Oscar with that adaptation. Seven more novels followed, as well as short story collections and a couple of film scripts. Nosotros dos en la tormenta delves into those turbulent years that Argentines prefer not to talk about. This work of fiction, the result of several years of research, is an icebreaker that seeks to end that silence.

Question. As a result of the film Argentina, 1985, there was much talk about that country that had just recovered democracy, happy and full of optimism. How would you describe the pre-coup Argentina in which the novel is set?

Answer. The Argentina of 1975 was very turbulent, very confrontational. Different sectors saw violence as a very legitimate tool to come to power or to exercise power. Different sectors – not only the guerrillas – used violence. In the government of Isabel Perón, Minister López Rega, who was her right hand, made an absolutely illegal use of power. The dictatorship that followed was the end of that way of managing. On the other hand, the Argentina of 1985 is an Argentina that has decided to say no to violence. It is no coincidence that President [Raúl] Alfonsín ordered to send the dictators to trial, but also the leadership of the [guerrilla movement] Montoneros.

Q. The trials against the repressors advanced, but those against the guerrillas did not. What happened?

A. We would have to take a look at the 1990s and [Carlos] Menem, the next civilian president, who pardoned both. Menem pardoned everyone with the idea of a clean slate, but in the 2000s, Kirchnerism decided to back down partially regarding those pardons. This partial reversal marks a break with the consensus of the 1980s regarding the repudiation of non-military violence of the 1970s. This continues to be the case, a rather controversial matter.

Q. Why? It is striking how, in a country that looks back so much, people hardly talk about the political violence of the 1970s. The topic is almost a taboo.

A. Maybe that’s the thing. I answer as a history teacher [he works in a high school]. We study history because what we want to understand is the present, not the past. And I think that our tendency to use historical arguments to validate current positions has to do with our deep political disagreements. As for not talking about the pre-coup 1970s, I think one of the reasons is to try not to legitimize the discourses that defend the dictatorship, which they do by pointing towards the deep divisiveness of the past.

Q. Is there self-censorship so as not to be treated as a fascists or denialists?

A. Undoubtedly, the fascists and the denialists take their view to extremes, so we just abstain to stay out of trouble. It is also uncomfortable in the case of Peronism. Montoneros was a Peronist movement, and it was the victim of a very strong illegal repression by the Peronist government throughout 1974 and 1975. It is uncomfortable for the inner memory. As a history teacher I don’t agree with discomfort silencing us. If the most elaborate, thoughtful and well-supported discourses keep quiet, the discursive space gets filled with those primitive and tasteless discourses. Public discussion is like power: it is always exercised, it always gets filled.

Q. Are cracks beginning to appear in that Argentine consensus of “dictatorship, never again”? I am thinking about the denialist discourse of Deputy Victoria Villarruel [from the far-right party La Libertad Avanza].

A. I think so, but I have an even broader position in favor of freedom of expression. It may hurt, but I know that you can’t keep people from talking about things, you can’t keep people from stating outrageous things. Doing so may be reassuring today, but it is detrimental for the future because those notions find forms of expression. That is why I believe that the best thought-out discourses have to face the political discussion.

From his childhood memories, Sacheri also mentions the forbidden books that his parents, both dentists, kept on the highest shelves of the family home. “During nap time, I used to climb those shelves. That restlessness hasn’t left me, I’m still attracted by uncomfortable things, the sacred bothers me, I mean when we make the profane sacred, like that attempt to sacralize the silences that we were talking about earlier,” he says.

He still lives in Castelar, not too far from his childhood home. To get to his studio one needs to go out into the garden and up some stairs. There, the books on the shelves are arranged by Argentine, Latin American and world literature. On the wall hangs a photograph of Ricardo Bochini, the greatest idol of the Independiente, as well as puzzles that the writer put together with his youngest daughter. His latest novel is also a puzzle, where the different voices — of guerrillas, family members and their victims — are pieces of a complex and multifaceted universe.

Q. How did you choose the characters?

A. They could have been a couple of militants from Montoneros or the ERP (the People’s Revolutionary Army, a guerilla with a Marxist-Leninist orientation), but I chose one of each, who would be friends and who would also show their differences, which were mostly theoretical. The novel can be read from whatever sympathy you have. What’s happening is that people who have a very critical position regarding the armed organizations like the novel because they read it from the side of the victims. And others, who have a much more empathetic position with those organizations, read it from those two guys.

Q. The two friends see violence as a tool to change the world. Are there collective dreams left in young people?

A. We live in a time of more sectoral dreams. I think about gender identities, for example, to name one, very strong among my teenage students. It is political, because it has to do with the public arena, even if it has nothing to do with a more egalitarian transformation in the distribution of goods.

Q. This year marks 40 years of democracy in Argentina. What achievements would you highlight?

A. The greatest achievements have to do with our cultural modernization. Argentina in 1983 did not have a divorce law; that was one of Alfonsín’s great struggles. Of course, not all areas modernized at the same speed; the legalization of abortion is super recent. But at the level of respect, freedom of expression and creative freedom, those things have become very well established. The consensus on democracy also worked out quite well. We vote every two years, and with all the turbulence that occurred, it is something that hasn’t stopped in 40 years. In the previous 40 years there are six coups d’état, and comparing seems important to me.

Q. What about the outstanding debts?

A. I think the biggest debt comes from the side of socioeconomic development. It is a terrible debt, and if we can’t solve it, it will end up hurting the achievements.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition