INSIDE

The first five years ANMF’s National Policy Research Unit reflects how research is integral to members and the community

International recruitment Can it be tackled ethically amid a global workforce shortage?

Attention to climate change The responsibility of nurses and midwives to take action and improve health outcomes

ANMF PRIORITIES 2023 A PUBLICATION OF THE AUSTRALIAN NURSING AND MIDWIFERY FEDERATION VOLUME 27, NO.10 JAN–MAR 2023

When they put their trust in you, it’s vital to have information you can trust )

Be up to date with the 2023 AMH Book or Online

We are constantly improving and updating the AMH. Here are some examples of the recent changes that may interest you:

• COVID-19 updates, including more detail on COVID-19 vaccines and the oral treatments molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir with ritonavir

• new monographs, eg eptinezumab for migraine prevention, diroximel fumarate for MS

• revised therapeutic information, eg for psoriasis, heart failure, stroke

• many new and revised drug interactions, eg aspirin + NSAIDs

There is a summary of key changes, including all new and deleted drugs, in every edition. The 2023 AMH is available in hard copy, online or available as an APP download to PC’s, Surface Pros and Mac computers for of ine use with Ctrl F search capability. To access full content a subscription is required.

For more information go to www.amh.net.au

Butler ANMF Federal Secretary

Butler ANMF Federal Secretary

The start of a new year often permits us to press the reset button, whether it’s setting new intentions, learning from the past or growing on the back of our achievements.

For the ANMF, the New Year is an opportunity to reflect on our wins, plan how to build on our successes and strategise where our focus is needed during 2023.

Towards the end of last year, we finally saw landmark legislation ensuring a registered nurse on-site and on duty 24/7 in all aged care facilities. The legislation also requires care providers to be more transparent and accountable regarding their use of taxpayer funding.

Further, the Government made a commitment to mandate the number of care minutes residents receive as part of its $3.9 billion aged care reform package.

While last November, the ANMF and HSU also secured an interim 15% pay rise for aged care workers through the Fair Work Commission.

These reforms will significantly strengthen the sector and will start to address much of the chronic understaffing.

The ANMF will work with key stakeholders to ensure these legislated changes will be applied when they are due to be implemented during 2023/4.

The union will also advocate for reducing public hospital admissions from aged care by increasing and embedding Residential In Reach (RIR) teams in public health services to meet local demand.

Further, the ANMF will push to mandate skill mix percentages or RN/EN/PCA care minutes and will lobby for better career pathways into and within aged care, including expanding the NPs role in aged care via a national plan.

Chronic staff shortages exacerbated by the pressures of COVID-19 over the past two years have created significant issues impacting all sectors.

Nurses and midwives across the board have reported feeling overwhelmed, anxious and exhausted, under the extreme conditions they work in day to day.

Many have reported the need for safe workloads, minimum staff ratios and skills mix, paid overtime, wage increases and safe working environments.

The ANMF is advocating to improve these essential conditions and will push for nurses and midwives to work to their full scope of practice, including the introduction of innovative models of care to reduce the burden.

Importantly, we will be working on effective recruitment and retention practices of nurses, midwives and qualified care workers to help further reduce the strain of the system in crisis.

This includes working with the government, alongside the Council of Deans of Nursing and Midwifery (Australia and New Zealand), the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA), the Australian and Nursing Midwifery Accreditation Council (ANMAC) and other peak nursing bodies on strategies to grow our nursing, midwifery and care worker workforce and ensure a sustainable pipeline for the future.

Industrial relations reform will make up a significant part of the ANMF’s work this year.

This includes creating less burdensome threshold requirements for taking protected industrial action; advocating for permanent employment and only limited use of fixed-term contracts, and keeping pressure on employers to comply with flexible working arrangement obligations rather than relying on casual work arrangements.

These priorities are just a few the ANMF will pursue during 2023. To read about these and others in detail, turn to this issue’s feature on page 8.

After many challenges, highs and lows over the past 12 months, the ANMF is ready and eager to advocate for better conditions for all our members. Working as a collective, we are unstoppable and will achieve the critical outcomes necessary to provide the care Australians deserve.

Importantly, we will be working on effective recruitment and retention practices of nurses, midwives and qualified care workers to help further reduce the strain of the system in crisis.

EDITORIAL Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 1

Annie

ANMF FEDERAL & ANMJ

Level 1, 365 Queen Street, Melbourne Vic 3000 anmffederal@anmf.org.au

To contact ANMJ: anmj@anmf.org.au

FEDERAL SECRETARY

FEDERAL ASSISTANT SECRETARY

ACT

NT

SA

OFFICE ADDRESS 2/53 Dundas Court, Phillip ACT 2606

POSTAL ADDRESS PO Box 4, Woden ACT 2606 Ph: 02 6282 9455 Fax: 02 6282 8447 anmfact@anmfact.org.au

OFFICE ADDRESS

16 Caryota Court, Coconut Grove NT 0810

POSTAL ADDRESS PO Box 42533, Casuarina NT 0811 Ph: 08 8920 0700 Fax: 08 8985 5930 info@anmfnt.org.au

OFFICE ADDRESS

191 Torrens Road, Ridleyton SA 5008

POSTAL ADDRESS

PO Box 861 Regency Park BC SA 5942 Ph: 08 8334 1900 Fax: 08 8334 1901 enquiry@anmfsa.org.au

OFFICE ADDRESS

535 Elizabeth Street, Melbourne Vic 3000

POSTAL ADDRESS PO Box 12600, A’Beckett Street, Melbourne Vic 8006 Ph: 03 9275 9333 / Fax: 03 9275 9344 MEMBER ASSISTANCE anmfvic.asn.au/memberassistance

OFFICE ADDRESS

50 O’Dea Avenue, Waterloo NSW 2017 Ph: 1300 367 962 Fax: 02 9662 1414 gensec@nswnma.asn.au

OFFICE ADDRESS

106 Victoria Street West End Qld 4101

POSTAL ADDRESS GPO Box 1289 Brisbane Qld 4001 Phone 07 3840 1444 Fax 07 3844 9387 qnmu@qnmu.org.au

TAS

OFFICE ADDRESS

182 Macquarie Street Hobart Tas 7000 Ph: 03 6223 6777 Fax: 03 6224 0229

Direct information 1800 001 241 toll free enquiries@anmftas.org.au

OFFICE ADDRESS 260 Pier Street, Perth WA 6000

POSTAL ADDRESS PO Box 8240 Perth BC WA 6849 Ph: 08 6218 9444 Fax: 08 9218 9455 1800 199 145 (toll free) anf@anfwa.asn.au

BRANCH SECRETARY

Matthew Daniel

BRANCH SECRETARY

Cath Hatcher

BRANCH SECRETARY Elizabeth Dabars

VIC

BRANCH SECRETARY Lisa Fitzpatrick

NSW

BRANCH SECRETARY

Shaye Candish

QLD BRANCH SECRETARY Beth Mohle

BRANCH SECRETARY Emily Shepherd

WA BRANCH SECRETARY Janet Reah

Annie Butler

Lori-Anne Sharp DIRECTORY

Front cover

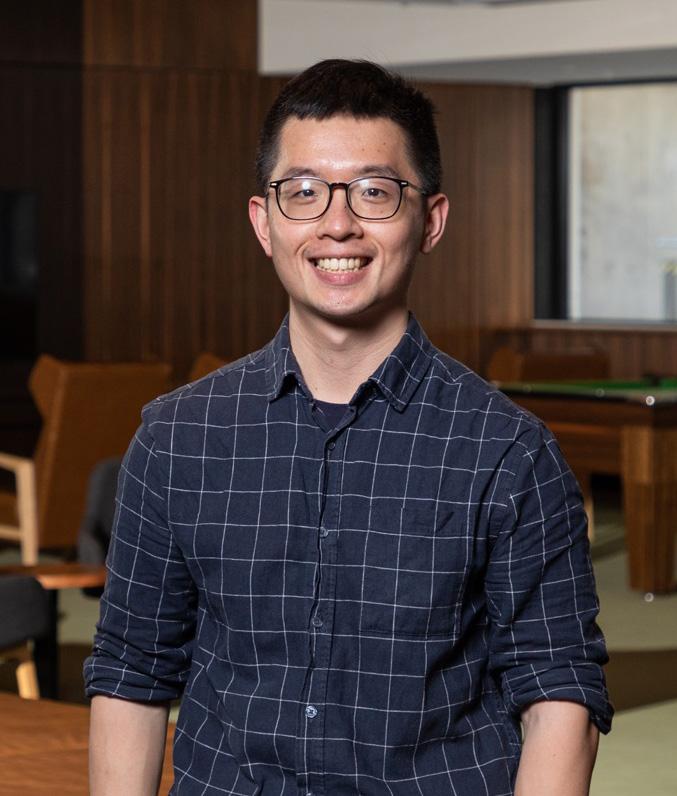

Advanced Practice Nurse Alison Wong, ED Nurse Practitioner Stuart Smith and Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner Juliane Samara

Image by Lydia Downe

Image by Lydia Downe

Editorial

Editor: Kathryn Anderson Journalist: Robert Fedele Journalist: Natalie Dragon Production Manager: Cathy Fasciale Level 1, 365 Queen Street, Melbourne Vic 3000 anmj@anmf.org.au

Advertising Heidi Hosking heidi@anmf.org.au 0499 310 144

Design and production

Graphic Designer: Erika Budiman instagram.com/pixels_and_paper_studio

Printing: IVE Group Distribution: D&D Mailing Services

The Australian Nursing & Midwifery Journal is delivered free quarterly to members of ANMF Branches other than New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia and ACT. Subscription rates are available via anmjadmin@anmf.org.au. Nurses and midwives who wish to join the ANMF should contact their state or territory branch. The statements or opinions expressed in the journal reflect the view of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the Australian Nursing & Midwifery Federation unless this is so stated. Although all accepted advertising material is expected to conform to the ANMF’s ethical standards, such acceptance does not imply endorsement. All rights reserved. Material in the Australian Nursing & Midwifery Journal is copyright and may be reprinted only by arrangement with the Australian Nursing & Midwifery Journal

Note: ANMJ is indexed in the cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature and the international nursing index ISSN 2202-7114 Online: ISSN 2207-1512

Moving state?

Transfer your ANMF membership

If you are a financial member of the ANMF, QNMU or NSWNMA, you can transfer your membership by phoning your union branch. Don’t take risks with your ANMF membership – transfer to the appropriate branch for total union cover. It is important for members to consider that nurses who do not transfer their membership are probably not covered by professional indemnity insurance.

ANMJ is printed on A2 Gloss Finesse, PEFC accredited paper. The journal is also wrapped in biowrap, a degradable wrap.

The ANMJ acknowledges the Traditional Owners and Custodians of this nation. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We celebrate the stories, culture and traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders of all communities. We acknowledge their continuing connection to the land, water and culture, and recognise their valuable contributions to society.

FEATURE 8

CLINICAL

16 Seeing the opportunity: Increasing the potential for eye donation 32 A clinical pathway for management of

related behaviours in RACFs FOCUS 43 Undergraduate nursing & midwifery students and graduate transition to practice

REGULAR COLUMNS 1 Editorial 2 Directory 4 News Bites 6 Lori-Anne 14 James 20 Environment 23 Legal 24 International 28 Research 30 Professional 31 Working Life 34 Industrial 36 Reflection 38 Issues 39 Research & Policy 40 Viewpoint 56 Healthy Eating

ANMF Priorities 2023

UPDATES

dementia

8

VOLUME

@ANMJAUSTRALIA ANMJ.ORG.AU

JAN–MAR 2023

27, NO.10

CONTENTS

Night owls beware: Bedtime procrastination impacts wellbeing

Bedtime procrastination correlates with increased daytime fatigue, shorter sleep duration and lower sleep quality.

New national centre on women’s mental health

A new national centre that addresses women’s mental health throughout all life stages has been launched.

The HER Centre for Women’s Health, based at Monash University, conducts research, treats women and improves awareness about women’s mental health issues occurring at all ages.

Women experience nearly twice as much depression as men, four times as much anxiety and 12 times the rate of eating disorders. Their mental illness involves a complex interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors, of which the causes of, and best treatments for, conditions such as depression, anxiety, trauma disorders, addictions, and self-harm are different to men’s.

HER Centre Director and Head of the Department of Psychiatry at Monash University, Professor Jayashri Kulkarni said for too long women’s mental health problems had been underdiagnosed and, in some cases, unrecognised.

“What we now know is, and science has told us, that many women of all ages are living with mental illnesses that may be related to female hormones and/or other parts of their biology.

According to CQUniversity (CQU) research, bedtime procrastination is prevalent with more than 50% of adults indicating they go to bed later than intended three or more days a week.

“Bedtime procrastination is the intentional delay of going to bed, without any external circumstances causing the delay - such as children, pets, or being on call for work,” CQU PhD candidate Vanessa Hill said.

“Many people procrastinate their bedtime from time to time, though for some people this is a regular occurrence that has a severe impact on their daily wellbeing. The results show that higher bedtime procrastination is correlated with shorter sleep duration, lower sleep quality and increased daytime fatigue.”

Higher bedtime procrastination correlated with lower selfcontrol and evening chronotype (night owls).

Bedtime procrastination is a growing area of research, with 55% of articles included in the systematic review published in 2020-2021.

“These results are an important first step for scientists to develop interventions to promote adequate sleep for people who have bedtime procrastination problems. For others who want to improve their overall health, this research shows that procrastinating bedtime could have a negative impact on their sleep,” Ms Hill said.

The study, ‘Go to bed! A systematic review and meta-analysis of bedtime procrastination correlates and sleep outcomes’ is published in Sleep Medicine Reviews

“A woman can experience pre-menstrual or menopause-related depression that is as serious as any other type of depression. Yet it can be easily written off as part of a ‘normal’ hormonal cycle. At its worst, such conditions can lead to serious mental illness or even suicide, without the true cause being identified.”

Environmental factors that impact many women and can contribute to mental ill health include experiencing violence, power imbalance, lower wages, and negative cultural expectations. Researchers in HER Centre are currently working on hormonebased treatments for women with menopausal depression. Clinical trials are also underway that are treating women with new forms of oestrogen, while educating health professionals about the need for them and their worth.

Visit: monash.edu/medicine/her-centre

NEWS BITES 4 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10

HER Centre Australia launch Jo Stanley (L) with Director Jayashri Kulkarni

NEW FUNDING TO ADDRESS INSTITUTIONAL RACISM IN AUSTRALIA’S HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

A new National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Synergy Grant of $5 million over five years will help to reform the delivery of hospital care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by addressing implicit bias and institutional racism within Australian hospitals.

Associate Professor and Waljen woman Tamara Mackean from the Guunumanaa (Heal) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program at The George Institute will lead the collaboration between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous researchers. The grant will look to understand and address the complex dynamics of racism, implicit bias and colonisation which

significantly impact the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and families.

“This project is focused on structural reform as a necessary part of healing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and families who have suffered ongoing trauma and injustice within the health system,” Associate Professor Mackean said.

The team will “bring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge of health and healing alongside Western biomedical knowledge to produce new meaning based on mutual respect,” Associate Professor Mackean said.

10 minutes of aerobic exercise with exposure therapy reduces PTSD symptoms

A short burst of aerobic exercise could promote a molecule in the brain that is crucial for learning to feel safe, according to a new study.

Exposure therapy is one of the leading treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), yet, up to half of all patients don’t respond to it.

But now, a study led by UNSW Sydney psychologists has found that augmenting the therapy with 10 minutes of aerobic exercise has led to patients reporting greater reduction to PTSD symptom severity six months after the nine-week treatment ended.

In the first known single-blind randomised control trial of its kind, researchers in Sydney recruited 130 adults with clinically diagnosed PTSD and assigned them to two groups. People in both groups received nine 90-minute exposure therapy sessions. At the end of each session, one group was put through 10 minutes of aerobic exercises, while members of the control group were given 10 minutes of passive stretching.

Findings, published in The Lancet Psychiatry, showed people in the aerobic exercise group on average reported lower severity of PTSD symptoms – as measured on the CAPS-2 scale – than those who had their exposure therapy augmented by stretching exercises at the six-month follow-up.

The goal of exposure therapy in treating PTSD is extinction learning, where a patient learns to equate something that up until now they have associated with trauma, with a feeling of safety.

Of note, there were no clear differences between the two groups one week after the treatment program ended, suggesting the benefits take time to develop.

More people seeking care at emergency departments, report shows

Public emergency departments (EDs) across Australia saw the highest number of patient presentations in 2020-21, a new report by the Australasian College of Emergency Medicine (ACEM) has revealed.

The finding was one of many in State of Emergency 2022 (SOE22) an inaugural annual report consisting of data from Australian public major, metropolitan, and regional hospitals.

The report shows that demand for emergency care has risen by 14% since 2016-17 – despite the population only growing by 5% – and that patients needing hospital admission were stuck waiting five hours longer than safe recommended targets for a bed, or an average wait of almost 13 hours.

According to ACEM, the data suggests the pressures were not caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and have instead been steadily increasing for years.

The report provides detailed insights into how many people present to EDs for mental health support, the busiest time and day in EDs, how long people are waiting for care, or a bed, and how many people give up and leave before even receiving treatment.

It also makes recommendations for strategic nationwide approaches to reduce pressures on EDs and the broader health system.

“EDs in every state and territory in Australia are in a state of emergency. There have never been more people requiring acute healthcare, people have never had such complex health needs, and people have never had to wait so long for urgently needed care,” ACEM President Dr Clare Skinner said.

Associate Professor Tamara Mackean

Photo:The George Institute for Global Health

NEWS BITES Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 5

Sharp ANMF Federal Assistant Secretary

More cake this festive season?

As we start a fresh year, I am continuing my long-standing tradition by sharing one of my favourite recipes in the Jan-Mar issue of the ANMJ.

If you have read my columns over the years, you may have gathered I have a passion for cooking and delight in sharing food with family, friends and colleagues. What you may not know is that I also love gardening and like nothing more than growing and sharing fresh produce from the backyard veggie patch.

At a recent social gathering, The Honourable Nicola Roxon (now chair of HESTA -Industry Super Fund) brought her delicious rhubarb and cinnamon cake.

Because I have an abundance of rhubarb growing in my garden, Nicola graciously shared her recipe with me.

The cake I baked was just as delectable as Nicola’s and was greatly enjoyed by family and friends. If you get the time to try it, I promise it will not disappoint.

Nicola’s rhubarb and cinnamon cake

INGREDIENTS

Batter

80g butter

300g brown sugar

2 eggs

1 tsp vanilla

300g flour

1 tsp bicarbonate soda

500g rhubarb stalks, sliced into 1 cm pieces, or add apple or pear to bulk up if needed

METHOD

250g full cream sour cream or thick yoghurt

Grated lemon zest

Topping

80g brown sugar 1 tsp cinnamon

1. Preheat oven to 180�C. Grease and line a deep rectangular cake tin (approximately 33 x 23 cm).

2. Cream together the butter and brown sugar.

3. Add the eggs and vanilla, and then fold in the sifted flour and bicarbonate soda.

4. Stir in the sour cream and zest, and once combined add the rhubarb pieces.

5. In a small bowl, mix together the brown sugar and cinnamon for the topping.

6. Pour the batter into the cake tin and finally, sprinkle the topping over the top of the batter.

7. Bake for at least 50–60 minutes. Test with a skewer, and continue to bake until skewer comes out cleanly.

8. Best served with crème fraiche or vanilla ice cream.

There is nothing like using ingredients you have grown yourself and always so much easier when you have it at the back doorstep, avoiding that last minute rush to the shops for ingredients. This year to my delight, my love, nurturing and hard work in the garden paid off, resulting in a bumper crop of rhubarb perfect for this cake.

After tasting the cake, my family and friends agreed my efforts at growing rhubarb was well worth it.

Nicola has kindly allowed me to share her rhubarb and cinnamon cake with you. I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

Lori-Anne

instagram.com/pixels_and_paper_studio LORI -ANNE 6 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10

Food styling and photo by Erika Budiman ©

Move to Maltofer®

Maltofer ® restores iron levels with significantly less constipation and better treatment compliance than ferrous sulfate.1–3

Maltofer® contains iron as iron polymaltose. For more information visit maltofer.com.au *In a study comparing iron polymaltose with ferrous sulfate in iron deficient pregnant patients. n=80.

References: 1. Ortiz R et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24:1–6. 2. Toblli JE & Brignoli R. Arzneimittelforschung 2007;57:431–38. 3. Jacobs P et al. Hematology 2000;5:77–83. Healthcare professionals should review the full product information before recommending, which is available from Vifor Pharma on request.

Maltofer is for the treatment of iron deficiency in adults and adolescents where the use of ferrous iron supplements is not tolerated, or otherwise inappropriate. For the prevention of iron deficiency in adults and adolescents determined by a medical practitioner to be at high-risk, where the use of ferrous iron supplements is not tolerated, or otherwise inappropriate. If you have iron deficiency, your doctor will advise you whether an oral iron treatment is required.

Maltofer® is a registered trademark of Vifor Pharma used under licence by Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd. For medical and product enquiries, contact Vifor Pharma Medical Information on 1800 202 674. For sales and distribution enquiries, contact Aspen Pharmacare customer service on 1300 659 646. AU-MAL-1900004. ASPHCH1150/ANMJ. Date of preparation August 2019.

Fewer pregnant women experience constipation with Maltofer ®1* Maltofer® 2% of patients Ferrous sulfate 23% of patients IS THEIR IRON CAUSING CONSTIPATION? Up to 54% of patients studied did not complete their full course of ferrous sulfate as prescribed.1*

ANMF PRIORITIES 2023

On the back of a positive 2022 with action to start improving conditions in our health, aged care and welfare sectors, the ANMF is determined to work on a list of priorities over 2023 that will support the professions and the health systems they work in. ROBERT FEDELE and NATALIE DRAGON report.

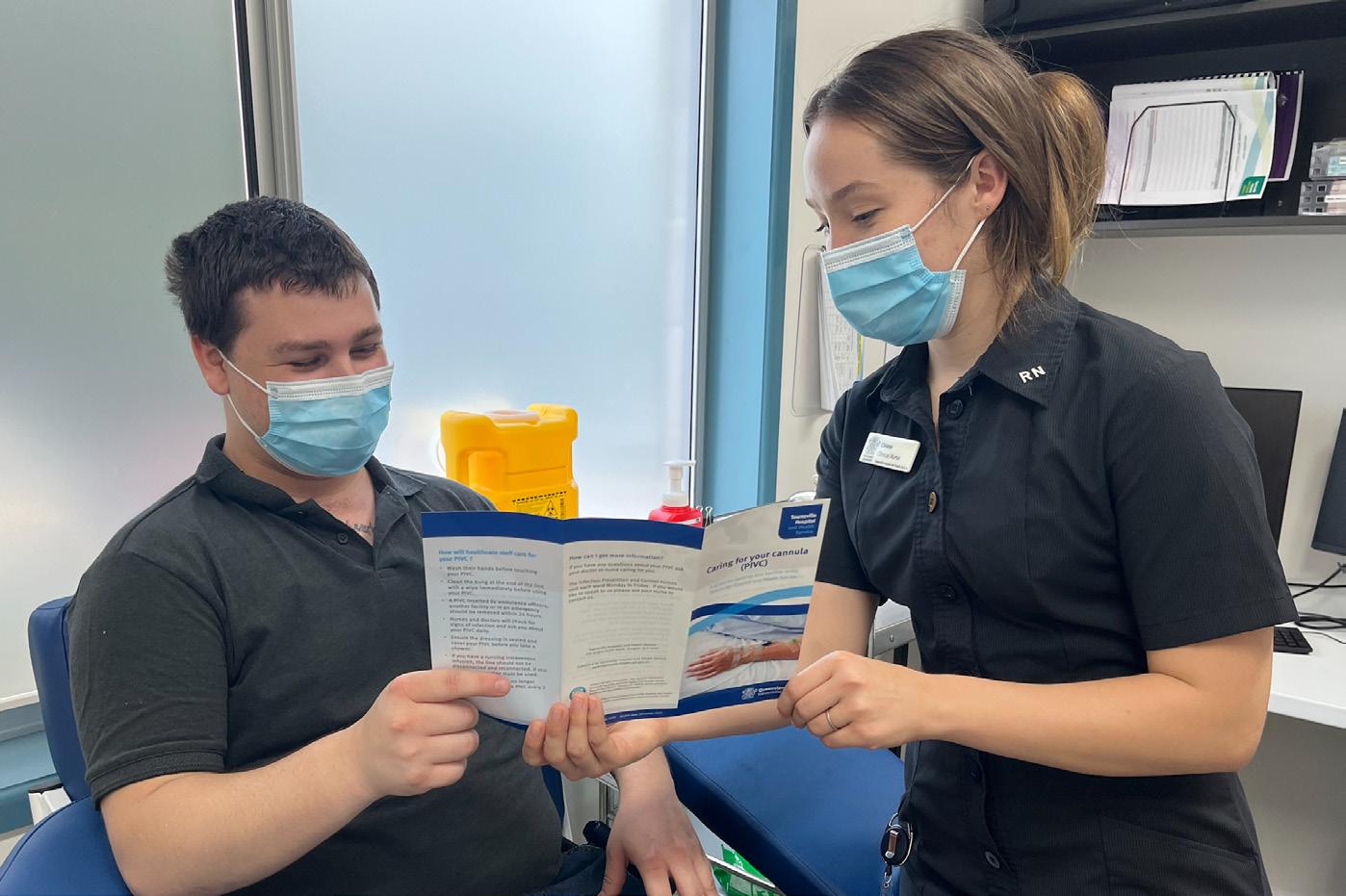

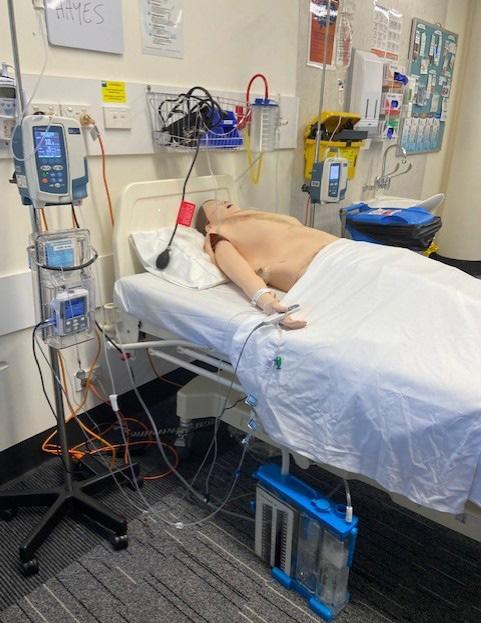

Advanced Practice Nurse Alison Wong, ED Nurse Practitioner Stuart Smith and Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner Juliane Samara lobbying politicians in Canberra last October.

Photo: Lydia Downe

Advanced Practice Nurse Alison Wong, ED Nurse Practitioner Stuart Smith and Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner Juliane Samara lobbying politicians in Canberra last October.

Photo: Lydia Downe

FEATURE

Gender equity

Australia is one of the few developed nations that does not actively set targets for gender equality. Yet, Australian women experience inequality in many areas of their working and social lives, including disparate wages, poverty, discrimination and gender-based violence.

Recent statistics show that the Australian gender pay gap is currently at 17.2%, which means females only earn 83 cents for every dollar earned by males.

Post-COVID, Australia has further slid down the rankings in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index to 50TH , down from 44TH in 2020 and 15TH when the index first launched. Australia is lagging in ‘economic participation and opportunity’ in women’s labour force participation rate, wage equality and earned income.

The Government’s plan for boosting wages in female-dominated industries will go some way to improving gender equity. The recent landmark Aged Care Work Value case has seen the Fair Work Commission grant a 15% wage increase for nurses and care workers in the sector as a “first step” towards securing better wages. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has indicated that more stages would follow, including closing the gender pay gap.

The Secure Jobs, Better Pay Bill is critical in giving nurses and aged care workers access to a collective bargaining system that allows for wage growth increasing gender equity across

workplaces. The introduction of a statutory equal remuneration principle is also aimed to reduce barriers to pay equity claims.

The ANMF is advocating for greater flexibility in the workplace for nurses, midwives, and personal care workers, many of whom are women juggling multiple work and caring responsibilities.

“We want to see genuine access to flexible work arrangements. The threshold for employers to refuse a flexible working arrangement and the factors on which this is based, should be reviewed and recalibrated to a modern workforce. Our members report reducing their hours, moving to casual positions, or even resigning due to being denied flexible work arrangements,” said ANMF Federal Secretary Annie Butler.

“We want to see better opportunities to balance work with personal responsibilities – our working hours and workplace conditions were set in a very different domestic context to what we have today.”

This includes a reduction of ordinary working hours from 38 to 32 on the negotiating table.

There is a lack of national policy to redress the reduced earning capacity during a woman’s lifetime. Women continue to earn less than men do and are more likely to be engaged in casual and part-time work, which are also contributing factors to the gender gap in retirement savings. Many women are currently living their final years in poverty –with the next generation of women also at risk. Superannuation reforms have been welcomed including the removal of the $450 per month superannuation guarantee (SG) eligibility threshold. The SG rate will also increase from 10.5% to 12% by 2025.

The ANMF will advocate for further super reform, including mandatory superannuation requirements on all periods of parental leave, the introduction of a benchmark on retirement adequacy that doesn’t disadvantage women, and a fair share of super tax concessions for women.

Promisingly, supporting women’s workforce participation and advancing gender equality were highlighted in the Albanese Government’s first Budget. Several provisions were made for better-paid parental leave entitlements, access to childcare, paid family domestic violence leave, all which contribute to closing gender inequity.

Federal Labor has also committed to implement in full the recommendations of the Respect@Work report into sexual harassment in Australian workplaces. After years of tireless advocacy and campaigning by the ANMF, the ACTU and the broader union welcomed the introduction of 10-days paid FDV leave.

The ANMF in 2023 will continue to call for a national plan on gender equality.

FEATURE Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 9

“We want to see better opportunities to balance work with personal responsibilities – our working hours and workplace conditions were set in a very different domestic context to what we have today.”

Improving equity in access to healthcare

Every Australian deserves access to quality and affordable healthcare, no matter who they are, or where they live. Yet, that’s not always the case.

The ANMF is calling for a range of measures to achieve health equity, including the review of health funding models, greater use of nurse-run clinics and nurse-led models of care, improving the capacity of the health system in rural and remote areas to meet community needs, and exploring digital telehealth opportunities, especially in rural and remote, and within nurse-led clinics.

According to ANMF Federal Secretary Annie Butler, a member of the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce, funding models should be reviewed so that they reflect the provision of healthcare, rather than activity, by providing incentives for outcomes such as improved health.

“The Taskforce is principally about improving primary healthcare,” Ms Butler explained.

“What we need to do in that space to ensure equal access for everybody and better outcomes for everybody.”

A key area of opportunity lies in giving nurse practitioners, and eligible midwives, expanded access to the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and removing barriers that prevent them from working to, and

extending and developing, their full scope of practice.

To achieve better integration between primary care, acute care, and aged care, Ms Butler says the ANMF is advocating for the expansion of models such as nurse-led clinics in primary healthcare, Queensland’s successful Nurse Navigators, and Canberra’s community-based nurse-led Walk-in Centres. Further, the ANMF would also like to see Urgent Care Centres, announced by the Labor Party, expanded beyond the first 50, and a commitment given to include nurse-led and multi-disciplinary options.

“The evidence consistently demonstrates that nurse-led models of care improve access to care, increase patient satisfaction and deliver better health outcomes,” Ms Butler said.

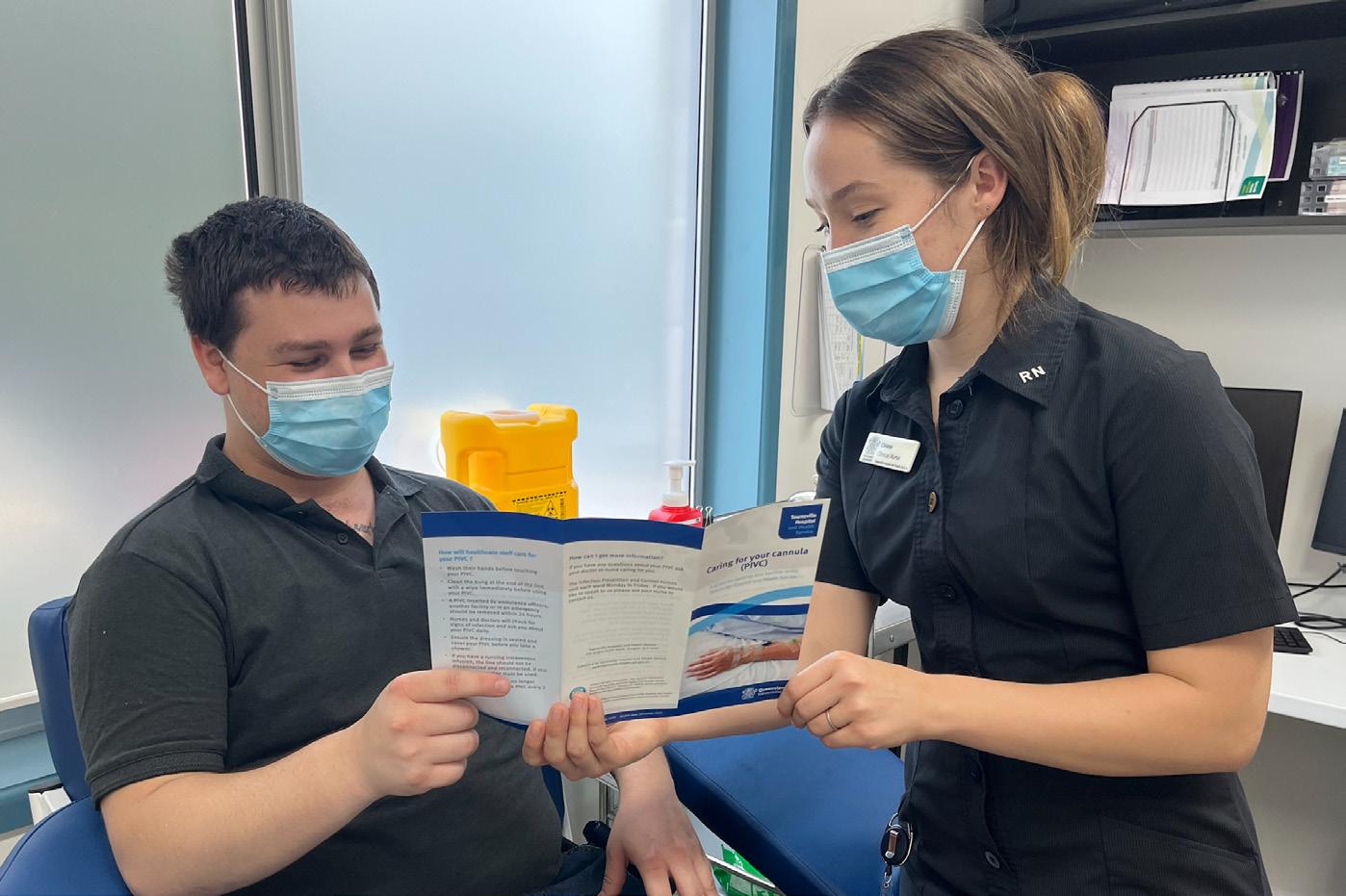

Advanced Practice Nurse Rachel Backhouse, who works across Canberra’s nurse-led Walk-in Centres, believes the communitybased model could be expanded nationally to improve access to healthcare.

Many patients access the centres because they are unable to see a GP, with one centre last year seeing 306 patients in a day, many

who would have otherwise presented to an Emergency Department and clogged up the hospital system.

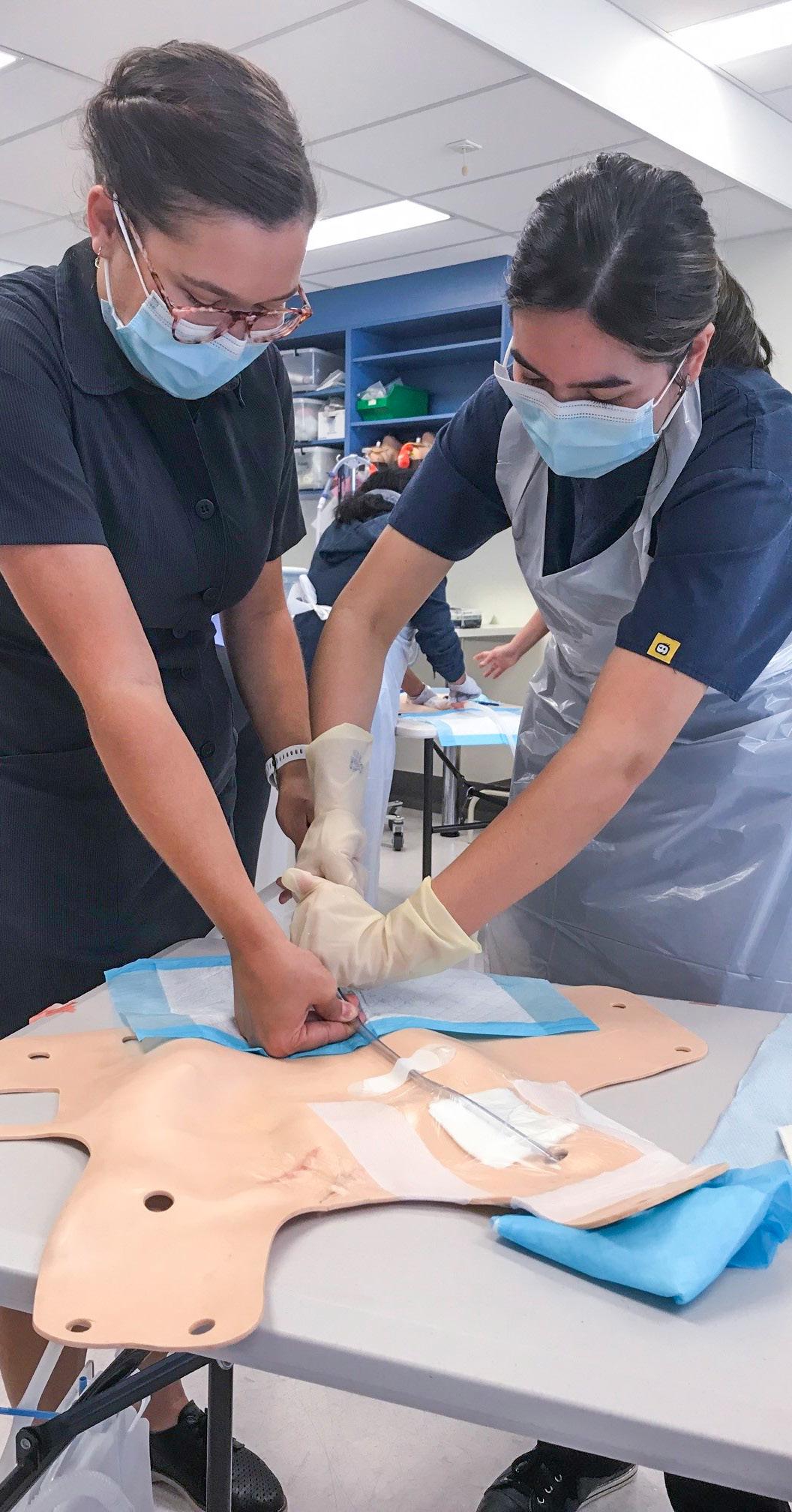

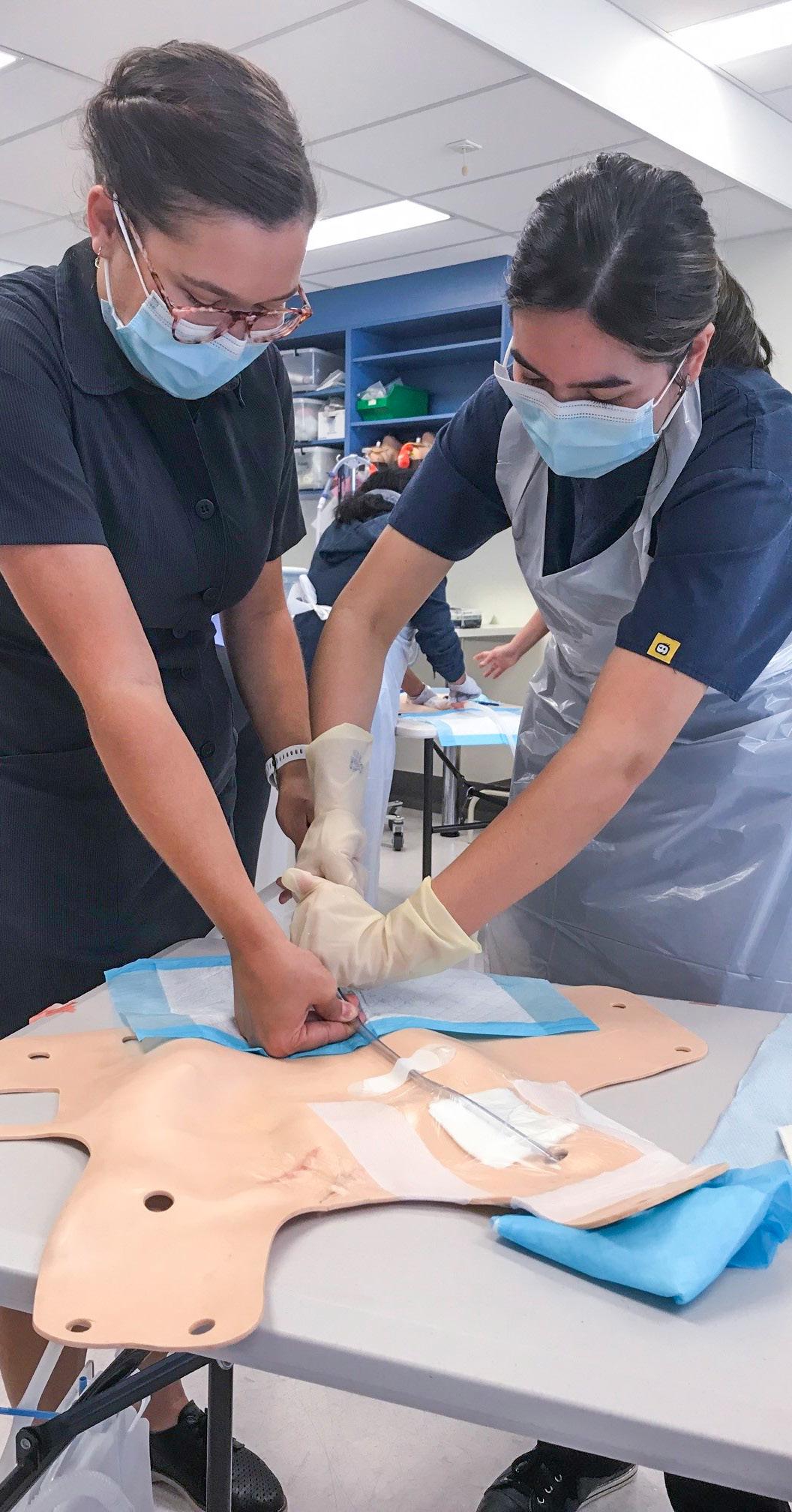

Nurses deliver care including ordering blood tests and X-Rays, and suturing. Nurse practitioners working in the clinics can also prescribe.

“We suture, we put casts on, we do a lot of things and we work with a lot of GPs as well. There’s a lot of work out there but we need to look at how we’re addressing primary healthcare in Australia because the emergency departments are just getting inundated with patients,” said Rachel, as part of a delegation of ANMF members who converged on Parliament House in Canberra last year to lobby politicians.

Extending and developing scope of practice for NPs will form one of the ANMF’s priorities in 2023.

Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner Juliane Samara, who works across 29 aged care facilities throughout the ACT, believes NPs can make a bigger difference in residential aged care and across the wider health system.

“We’re not a replacement workforce. We don’t replace doctors; we never want to replace doctors. We want to work as multidisciplinary teams. Nurses do that inherently and we do it well,” she said.

“The best models that I see are where everybody in the team is an equal member of that team. There’s no hierarchy but everybody knows what their role is and everybody knows that they can talk to each other, refer to each other and work together when there’s a need.”

FEATURE 10 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10

“What we need to do in that space to ensure equal access for everybody and better outcomes for everybody.”

Aged care reform

After years of declining quality in care and neglect for elderly Australians, the Albanese Government acted on its election promises by commencing long-overdue aged care reform.

Landmark legislation, spearheaded by the Aged Care Amendment (Implementing Care Reform) Bill 2022, passed into law on 27 October 2022, will require aged care providers to have a registered nurse on site, and on duty, 24/7, from 1 July 2023. Aged care providers will also need to be more transparent and accountable regarding their use of taxpayer funding, including regularly publishing financial information on what they spend on care, nursing, food, maintenance, cleaning, and profits.

In its 2022-23 Budget last October, the Albanese Government, which labelled workforce its biggest priority, unveiled a $3.9 billion package of aged care reforms. They included a commitment to mandate the number of care minutes residents receive – beginning with 200 care minutes, including 40 from registered nurses, from 1 October 2023, and 215 care minutes, including 44 from RNs, from 1 October 2024.

ANMF Federal Secretary Annie Butler said the start of aged care reform offered renewed hope for members working in the sector.

“While implementation of these crucial reforms will take some time, ANMF members and aged care workers across the country will finally see the first real steps

towards actually fixing the aged care sector,” Ms Butler said.

“The implementation of a 24 hour RN presence and mandated minimum staffing laws will help address the chronic understaffing in the aged care sector.”

Other legislative improvements introduced last year included a Star Rating System to help older Australians compare residential aged care services; an enforceable Code of Conduct for aged care providers and workers; strengthening governance by placing new reporting requirements on providers; and extension of the Serious Incident Response Scheme (SIRS).

At Parliament House to witness passing of landmark RN 24/7 legislation, Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner Juliane Samara said having nurses around the clock in aged care was vital.

“People don’t stop dying and getting sick just because the roster finishes at 10 o’clock at night. They [residents] deserve and need registered nurses to be there to assess, treat and manage whatever symptoms they’ve got, around-the-clock,” she said.

“RN 24/7 will allow a range of facilities that function through a loophole in the system

at the moment to deliver a higher, safer, quality of care,” added NSW aged care RN Glen O’Driscoll.

Meanwhile, other budget measures included a new national registration scheme for personal care workers, costing $3.6 billion, home care administration and management fees capped and exit fees abolished, and a dedicated Aged Care Complaints Commissioner.

In 2023, another key priority for the ANMF will involve reducing public hospital admissions from aged care by increasing and embedding Residential In Reach (RIR) teams, including dementia specialists and nurses with psych-geriatric expertise, in public health services to meet local demand. The union also wants to expand the role of NPs in aged care, via a national plan.

More broadly, the ANMF is advocating for better career pathways into, and within, aged care. This includes funding transition programs that give early career nurses an opportunity to undertake post-graduate studies in gerontology, and supporting better skill mix and retention in the sector.

In a historic win, the ANMF’s aged care case for improved wages in the sector made inroads, with aged care workers securing an interim 15% pay rise after the Fair Work Commission (FWC) handed down its decision on the Work Value Case last November.

In summarising its decision, the FWC said the increase was “plainly justified by work value reasons”, supporting the ANMF’s claims that the work of aged care workers had never been properly valued and is in fact significantly undervalued.

FEATURE Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 11

“While implementation of these crucial reforms will take some time, ANMF members and aged care workers across the country will finally see the first real steps towards actually fixing the aged care sector.”

Industrial relations reform

In late October, the Albanese Government took action to finally get wages moving, improve working conditions and achieve gender-equality across workplaces, with the introduction of its industrial relations legislation, the Secure Jobs, Better Pay Bill passed into law in December.

The Bill modernises Australia’s bargaining system, including better options for multi-employer bargaining rather than only enterprise bargaining. For example, unions could negotiate one pay deal across multiple employers in sectors such as aged care, with the more uniformed agreement shifting the power back to workers and increasing the ability to win fair pay rises.

“Our existing bargaining system is outdated and unfair and severely disadvantages workers in smaller, care industries – nurses and carers working in aged care simply have no power,” ANMF Federal Secretary Annie Butler said.

“Many of our members have been ‘lockedout’ under the existing bargaining system and haven’t had a proper wage rise in years,

with their conditions deteriorating to the point where more and more workers have abandoned their profession, leaving nursing homes dangerously understaffed.”

In Canberra to watch the Bill being introduced, NSW aged care registered nurse Glen O’Driscoll said it would help assist in recruiting and retaining staff.

“A casualised workforce has very little clout, very little security to tenure and very little benefits that a full-time employee gets. If this bargaining agreement can address those issues, that’s a plus, because it will assist retention in the industry and stop the exodus of skilled workers from our floor.”

Key focus areas the ANMF will lobby for industrial relations reform include creating

less burdensome threshold requirements for taking protected industrial action; advocating for permanent employment and only limited use of fixed term contracts; and keeping pressure on employers to comply with flexible working arrangement obligations rather than relying on casual work arrangements.

Importantly, the Secure Jobs, Better Pay Bill also introduced significant reforms to address the gender pay gap and discrimination.

The Fair Work Act will include an explicit prohibition on the sexual harassment of workers, prospective workers or a person conducting a business in connection with work. Meanwhile, the Fair Work Commission will be bolstered with two new expert panels, on pay equity, and the care and community sector, to help determine equal remuneration cases and certain award cases.

“This Bill is a step towards ending the wage crisis that working people have been battling through for a decade,”

ACTU Secretary Sally McManus said.

“This Bill will continue the work of making workplaces safer for women and making it easier for women to access and re-enter the workforce.”

FEATURE 12 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10

“Our existing bargaining system is outdated and unfair and severely disadvantages workers in smaller, care industries – nurses and carers working in aged care simply have no power.”

Nursing, midwifery and care worker workforce

Globally there is a shortage of nurses and midwives. The pandemic has exacerbated health workforce shortages worldwide with many countries ill equipped and struggling to maintain adequate health service provision.

The Australian Department of Health forecast a national nursing shortage of about 85,000 nurses by 2025, growing to 123,000 nurses by 2030, in a detailed report on Australia’s future health workforce published back in 2014.

A broad range of factors influence the supply including the number of new graduates; the number of overseas nurses entering the Australian workforce; retention and workplace issues; and recruitment, along with the image of nursing.

For the past three years, nurses and midwives had been called to action like never before, ANMF Federal Secretary Annie Butler said.

“Many have reported feeling overwhelmed, anxious and exhausted. Anecdotally while many have left the profession altogether others have chosen to stay but have reduced their hours to cope.

“Lack of effective recruitment and retention of nurses and qualified care workers will only put further strain on a system at breaking point.”

A raft of recent measures including the Aged Care Bill, IR reforms, and flexible working arrangements may help to mitigate the exodus of those leaving the professions with better pay and improved conditions in sectors such as aged care. In addition, the government’s cost of living measures include for greater flexibility around paid parental leave and increased financial support for early childcare and education to support families.

The ANMF is working with government, alongside the Council of Deans of Nursing and Midwifery (Australia and New Zealand), the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA), the Australian and Nursing Midwifery Accreditation Council (ANMAC) and other peak nursing bodies on strategies to grow our nursing, midwifery and care worker workforce and ensure a sustainable pipeline for the future. Proposed strategies include fully funded or subsidised undergraduate and postgraduate education and scholarships, reintroduction of HECS exemption, and an increase in the number of undergraduate places for both nursing and midwifery along with increased

funding and support for re-entry and return to practice programs.

“We need solutions to retain our current skilled workforce while we plan for how to recruit the next generation of nurses and midwives,” Ms Butler said.

Nurses and midwives have identified safe workloads, minimum staff ratios and skills mix, being paid overtime, wage increases and safe working conditions as key retention issues. Along with improved work satisfaction and being able to work to full scope of practice, in innovative models of care, and the ability to deliver high quality care.

The ANMF will continue to advocate for national ratios with federal health funding linked to minimum staffing requirements in all state and territory public health programs.

Mental health resources, adequate staff support and support programs for new nurses and midwives have also been highlighted as priority areas by members. The ANMF has welcomed the Albanese Government’s commitment to establish the National Nurse and Midwife Health Service which will provide health and wellbeing support for nurses and midwives across the country.

Supporting the development for a sustainable and experienced rural and remote workforce and greater efforts in our First Nations health workforce are also priorities for the ANMF in 2023.

FEATURE Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 13

“Lack of effective recruitment and retention of nurses and qualified care workers will only put further strain on a system at breaking point.”

James Lloyd ANMF Federal Vice President

Student to RN – Our future

A successful student-to-graduate transition is critical in healthcare.

In this post-Covid world, healthcare workers, particularly nurses, midwives, and carers, are in high demand. But the last three pandemic years have resulted in a considerable increase in burnout, hence the need for a new workforce to be trained to meet this requirement. This new workforce will encounter immediate and extensive demands of an overstressed hospital system. So how can student RNs and midwives transition successfully to the workforce and lessen their chances of burnout and disillusionment?

Many years ago, at the start of my nursing career, I remembered the notion of “Eating our young”, coined by Judith Meissner in a 1986 article where she described the hostility new nurses faced at the hands of more experienced colleagues. The author even uses the term “a kind of a genocide” and “insidious cannibalism” to describe how we were treating our young (‘young’ meaning all new nurses and midwives, not an aged-based description) and its effect on our professions. This was a generation ago.

Nursing and midwifery were lifting slowly out of the ‘command and control’ system of the past. How we treated our young, denying their previous life experiences, skills they already earned, and taking initiative was frowned upon. Judith Meissner ended her article by stating, “If they are not nurtured as they develop, professional extinction beckons”.

Numerous studies have shown that limited support, unprofessional workplace behaviours, high workloads, and assigning responsibilities beyond their skills hamper the successful transition and integration of our student nurses and midwives. In a post-Covid world, there is a significant workforce shortage in nursing and midwifery professions. Our graduates transitioning to the workplace are being asked to work beyond their capacity. We are asking them to grow up quickly. The luxury of a smooth and steady transition from University/TAFE to the workplace is being truncated with the current demands.

Many students, prior to their graduate year, have external demands such as working to support themselves or having family responsibilities. These external stressors can result in decreased resilience before entering the new workplace. With external baggage, their early experiences in their graduate year will impact their level of satisfaction and could influence long-term career intentions.

What factors can influence a new graduate nurse’s transition into practice?

Teaching resilience – During the orientation of new graduates, resilience - a key ingredient of successmust be taught. Resilience is the ability to bounce back from adversity. It is a necessary skill for coping with life’s inevitable obstacles and one of the key

ingredients to any successful career. It is built by creating supportive work environments, developing a sense of belonging, having goals, celebrating successes, and having a good work-life balance. Building resilience in our graduates will ensure they have every chance of having a long and satisfying career in nursing or midwifery.

Creating a healthy work-life balance – A healthy work-life balance is crucial to a successful career. Generally, work has proven to be good for mental and physical health and wellbeing. But a poor work-life balance can cause stress and burnout. So as employers, mentors, and friends of new graduates, we need to encourage them to develop a rich and fulfilling life outside of work. This is a constant rebalancing act, and the equilibrium always shifts with life’s challenges.

Mentoring – Research indicates that effective mentoring is key to a graduate’s transition to the workplace. A good mentor must be objective and analytical and offer emotional support. A negative experience (for either the mentor or mentee) can have a detrimental effect on the relationship, such as suppressed student learning or the mentor unwilling to accept new students. The student-mentor bond is crucial to the new graduate’s successful transition and long-term stay in the profession.

Supporting emotional wellbeing – Finally, in my experience, the support of the emotional wellbeing of the new graduate is crucial. The new graduate needs to transition to a new workplace, develop new relationships, battle carer’s fatigue, cope with new stressors, work unfamiliar hours, and still take care of the emotional wellbeing of themselves and others (eg. family and partners) outside work. This convergence of competing stressors can challenge even those with a high emotional reserve. As mentors, role models and work colleagues, we need to look for the signs of burnout in our new grads. When seen, step in - open a conversation, ask if they need any help, listen, reassure, validate their feelings and concerns, encourage them to seek external professional help, and support without judgement.

This modern workplace can be a reality shock. Our new graduate nurses are entering a work environment characterised by nursing staff shortages, increasing patient acuity, Covid-19, and limited access to clinical support. A positive workplace environment makes a job more fulfilling and for a graduate, this is even more important, as it facilitates a more effective transition. In contrast, negative early experiences impact new graduate nurses’ satisfaction levels and can influence long-term career intentions.

Let’s empower our new graduates.

JAMES 14 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10

Nurse & Midwife Support

o ers free, confidential and 24/7 health and wellbeing support to nurses, midwives and students across Australia.

Seeing the opportunity: Increasing the potential for eye donation

By Hayley M Hall and Sofia Karageorge

Corneal transplants can restore sight for people in the community, yet there is an imbalance in supply and demand.1 Worldwide, a staggering 12.7 million people are waiting on a corneal transplant. Annually, approximately 185,000 corneal transplants occur from 284,000 donated corneas; equating to only one in 70 transplants successfully received.1 In 2020, 2,277 Australians received corneal transplants from 1,318 donors.2

Palliative Care Units (PCU) inherently have a high death rate annually and staff often overlook these patients as potential eye donors.3 Palliative care patients in a ward-based setting are not suitable for solid organ donation; however, many patients are eligible to be eye donors.4,5 Facilitating the donation opportunity can fulfil a patient’s desire to help others in the community, acknowledge their registration status

on the Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR), their preferences outlined on their Advanced Care Directive and provide purpose for their families.4 Families who support eye donation can consent to whole eye or corneal donation. Whole eye donation includes the cornea, which restores sight and the sclera, which is used for surgical reconstruction in patients who have suffered from eye trauma or disease,

including glaucoma.2 Each eye tissue donor can potentially transform the lives of up to 10 people in the community.6

OVERVIEW

A quality improvement project was initiated in a 24-bed PCU in an outer-metropolitan 671-bed tertiary hospital. In 2017 the PCU had 553 deaths; however, only 11 eye donations occurred. While the hospital had two Donation Specialist Nursing Coordinators (DSNC) based in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), eye donation was rarely considered for the PCU patients. Despite common misconceptions amongst healthcare professionals and the community, many patients who die in the PCU can donate their eyes.3 Whilst there are exclusion criteria, cancer and advanced age are not automatic exclusions.5 Corneal retrievals can occur up to 24 hours post death allowing staff adequate time to gain consent and alert the Lions Eye Donation Service (LEDS) with enough time for the one-hour retrieval process to occur.5

BACKGROUND

Exploration of eye donation was assumed to be standard practice for end-of-life care (EOLC) patients in the PCU; however, it was not initiated by staff. Despite having prepacked forms for completion by the bedside nurse when a patient died, including eye donation consent paperwork. There was no ward procedure for eye donation; instead,

16 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 CLINICAL UPDATE

it would predominantly occur if the family or patient raised the subject. A gap in this process was identified when a new nursing team member commenced on the PCU.

PROJECT OUTLINE

Two senior PCU nurses decided to reconsider the existing procedures. They became the Clinical Leads for eye donation in the palliative care setting. If a patient died in the ICU, staff would routinely refer to the DSNCs to check the AODR and screen the patients for organ, eye and tissue donation. While patients dying in the PCU would not be suitable for solid organ donation, many meet the criteria for eye donation.5,7 Unfortunately, a majority of potential inhospital donors are never considered for eye donation.8 Minimal donations occurred in the PCU as ward staff had limited knowledge about the eligibility criteria and the process of facilitating a donation. For eye donation to become a routine part of EOLC, education and support of the nursing staff are crucial.7

METHOD

Prior to the provision of education, the Clinical Leads sent out a survey to the PCU nursing staff to establish gaps in knowledge and attitudes to eye donation. The survey identified the following barriers to eye donation: a lack of knowledge regarding the donation process, misconceptions on eligibility and exclusion criteria, low confidence levels in conducting the donation conversation and

staff perception that raising eye donation with grieving families is inappropriate. Whilst the two Clinical Leads had basic knowledge surrounding the donation process. They set out to undertake further training and education to build knowledge and develop communication skills before implementing any new procedures.

The Clinical Leads sought education opportunities by connecting with DonateLife Victoria (DLV) staff based in the ICU and attending an education session and tour of the Lions Eye Donation Service (LEDS). DonateLife conducted formal training sessions, which the Clinical Leads attended. These included ‘Introductory Donation Awareness Training’ followed by ‘Core Family Donation Conversation’ workshop and ‘Practical Family Donation Conversation Workshop’.9 This knowledge enabled them to educate and up-skill ward staff, making the offering of eye donation standard practice on the ward.

The Clinical Leads conducted a staff inservice, which provided an overview of eye donation and addressed the perceived barriers from the survey. Given that the eye donation consent paperwork had been easily accessible and never used, the Clinical Leads implemented a new procedure to prompt staff to consider eye donation for every patient. With the information provided by LEDS 7 and guidance from the DLV staff, the Clinical Leads developed a screening tool to enable staff to

quickly determine a patient’s eligibility to donate their eyes and establish whether they were a registered donor. Nurses complete the screening tool for every patient on admission to the PCU. Once the goal of admission progresses to EOLC nurses request LEDS or DLV staff to conduct a register check. Donor register status was then reflected on the screening tool and the ward handover sheet. The screening tool was also valuable for highlighting a patient’s objection to organ and tissue donation. Patients’ organ and tissue donation preferences are often outlined in their Advance Care Directive or on the AODR.

The Clinical Leads provided 1:1 staff training to each nursing staff member. Topics covered include how to interpret and utilise the screening tool, identification of a registered donor and the timing and process of the donation conversation.

Instructions on completing the mandatory paperwork required for eye retrieval and donation to proceed were also part of the training. The staff survey also identified that most staff did not feel comfortable raising eye donation with families due to lack of experience and feeling it is insensitive to raise following a patient’s death.

Nurses were invited to observe donation conversations conducted by Clinical Leads to provide exposure to and alleviate any misconceptions around aggression or distress from families during these discussions. A key message taken from the DonateLife training

Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 17 CLINICAL UPDATE

relayed to staff is that alerting families to the possibility of donation offers them an opportunity rather than trying to take something from them.9 At times, the LEDS conducted corneal retrievals on the ward, and nurses were encouraged to watch the procedure to eliminate any stigma attached to the retrieval process. Better understanding this empowered staff to confidently answer questions that patients or their families may ask. It also provided an opportunity for questions directed at the LEDS staff member undertaking the retrieval. Understanding how the corneal retrieval process works and the benefits experienced by the recipients enables staff to understand and support the process. The evidence suggests that explaining the benefits of corneal donation to the families of potential eye donors increased the consent rate and should be included in training.11

RESULTS

The initial focus of the quality improvement project in early 2018 included the Clinical Leads raising awareness of eye donation on the PCU via provision of education. The screening tool was implemented once there was basic knowledge around the eye donation process. Following the introduction of the screening tool and 1:1 education, there was a marked increase in the number of donation conversations occurring on the ward.

January – June 2018:

The Clinical Leads conducted ward inservices to raise awareness about donation and collected data on 206 patients who had died from 1 January 2018 to 30 June 2018. Half of these patients met the eligibility criteria

for eye donation. Out of 103 potential eye donors, staff approached nine families; two families declined, and seven consented to eye donation. Staff missed 91% of potential donors.

July – December 2018:

The Clinical Leads introduced the screening tool, and it was completed for every patient on admission. Clinical Leads collected data on the 351 patients who had died from 1 July 2018 to 31 December 2018. Of these, 128 patients met the eligibility criteria for eye donation. Fifty-one percent of potential eye donors were missed (40% reduction). Forty percent were offered eye donation by staff; 34 families declined and 28 consented to eye donation.

January – December 2019:

The screening tool was now a routine part of the ward admission procedure. All nursing staff had received 1:1 training from the Clinical Leads with an opportunity to observe or conduct a donation conversation. The Clinical Leads collected data on the 646 patients who had died between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019 and 183 met the eligibility criteria for eye donation. The screening tool reduced the missed potential donors to only 10%, 90% of those eligible were offered eye donation by staff; 81 families declined, and 83 families consented to eye donation.

2020 – 2021:

In 2020, there was a 13% decrease in eye donors nationally compared to 2019 due to service interruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected staffing levels and allowance of visitors on the ward.11,12

Despite the national trend, the PCU remained consistent throughout 2020 and 2021, with 88% of eligible patients offered eye donation in 2020, leading to 67 consents and 83% in 2021, resulting in 58 consents.

Over the lifespan of the project, 87% of identified registered donors consented to donation. The screening tool provided a place for nursing staff to document any comments made by the family when the donation conversation occurred. Of the recorded comments when a family declined, 19% stated it was because they “had never discussed donation with the patient”. Conversely, 24% had spoken with their relative and knew it was something they didn’t want. When raising via telephone, 52% consented.

Data was collected on 2,436 deaths since the beginning of the project. Of these 1,544, 60% were medically unsuitable. Of the 992 eligible patients, 212 (21%) were not

800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Deaths 2018 2019 2020 2021 Offered donation Missed potential donors 2018 2019 2020 2021 Eligible Offered donation PCU EYE DONATION STATS POST SCREENING TOOL AND STAFF 1:1 EDUCATION MISSED POTENTIAL DONORS VS DONATION OFFERED Missed potential donors Consented Declined CLINICAL UPDATE 18 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10

offered donations due to the LEDS being unable to accept because of time constraints, excess supply, decreased capacity during holiday periods, and cancellation of elective surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic.

DISCUSSION

Undoubtedly staff education and the implementation of the screening tool reduced the missed potential eye donors. The Clinical Leads considered the correct timing of the donation conversation and whether it was more ethical to speak about donation when the patient was still alive, providing the opportunity to be involved. As solid organ donation is extremely time sensitive, it is clinically imperative to conduct the donation conversation while the patient is alive, although acknowledging that in most situations, the patient would be unresponsive and unable to participate. The Clinical Leads agreed that admission to the PCU already brings big emotions for patients and their families. Nursing staff feared that raising the topic of donation pre-death could be considered pre-emptive and be ill-received. However, the choice of conversation timing is a limitation, as many families mentioned being unsure what their relative would want as a reason for declining donation. Knowing a patient’s status on the AODR can help families decide whether to support eye donation.13 Requesting donor register checks before raising eye donation with families was beneficial as families are made aware of any preferences expressed by the patient before they died. Periodically staff stated they could not raise eye donation at the time of the patient’s death for reasons such as relatives departing immediately or not attending the ward. Some families are exceptionally distressed, making it difficult to conduct any formal conversations. The Clinical Leads found that raising eye donation via a phone call to the senior available next of kin (SANOK) after death yielded positive consent rates. It is possible that when asked in person, relatives may have felt pressure to make an immediate decision. In contrast, a donation conversation via telephone allows for a decision to be made in a space they felt comfortable and receive it at a time when their emotions were less heightened.14

A common misconception highlighted in the staff survey was the belief that certain religions prohibited donation. Comments documented on the screening tool where families had declined eye donation, citing religious beliefs as the reason for declining, also reflected this misconception. As a result, a religious resource folder was compiled with statements of support for the donation process from heads of major religions, which were obtained from DonateLife resources.15 This was a useful tool for families who were conflicted on what the stance of the religion may be on donation.

LIMITATIONS

This was a single-site quality improvement project. While the program worked exceptionally well on this PCU, an identical model may not be suitable in other settings for reasons including the increased service demands and resourcing implications for the health service if there was a significant increase in donors.

While staff overlooked some potential donors due to human error, the most common reason documented for not raising donation was family aggression. Stressors created by the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in these incidences occurring more frequently.12,16

CONCLUSION

A simple change in practice has resulted in widespread benefits. Staff have described a sense of fulfilment gained by offering the donation opportunity to families during a sad time. We hope there are also benefits for the families involved who generously consented to eye donation. Educating staff to consider all patients for donation has resulted in a decrease in missed potential donors and an increased number of corneal donors and therefore transplants received by community members. To date 302 families from the PCU have consented to eye donation and have restored sight in approximately 503 recipients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the DSNCs based at Austin Health over the project’s lifespan for their overwhelming encouragement and guidance –Katheryn Hall, Ciara McGuigan, Sarah O’Connor, Clare Healy and Mikaela Henry. The LEDS staff who have always been generous with their knowledge – Dr Prema Finn, Adrienne Mackey, Gavin de Loree, and Prue Armstrong. They would also like to acknowledge the support of their Nurse Unit Manager, Hilary Hodgson and the PCU staff who have embraced this addition to the care they provide. Approval was obtained by the Austin Health ethics committee to evaluate this process. This research did not receive any funding. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS

Hayley M Hall RN Grad Dip Palliative Care is an Associate Nurse Unit Manager on the Palliative Care Unit, Austin Health

Sofia Karageorge RN is an Associate Nurse Unit Manager on the Palliative Care Unit, Austin Health

REFERENCES

1. Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M, Acquart S, Cognasse F, et al. Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2016 Feb 1;134(2):167.

2. Eye tissue donation: Why become an eye donor? | CERA [Internet]. cera.org.au. 2020 [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: cera.org. au/lions-eye-donation-service/why-becomean-eye-donor/

3. Gillon S, Hurlow A, Rayment C, Zacharias H, Lennard R. Obstacles to corneal donation amongst hospice inpatients: A questionnaire survey of multi-disciplinary team member’s attitudes, knowledge, practice and experience. Palliative Medicine. 2011 9 September;26(7):939–46.

4. Eye and tissue donation awareness [Internet]. DonateLife. [cited 2022 Sep 24]. Available from: donatelife.gov.au/get-involved/eyeand-tissue-donation-awareness#Raisingawareness

5. Roach R, Broadbent AM. Eye Donation in Sydney Metropolitan Palliative Care Units. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010 Feb;13(2):121–3.

6. Williams L. Eye Donation Explained [Internet]. LifeSource. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 1]. Available from: life-source.org/latest/eyedonation-explained

7. Identification and referral of eye donors [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 23]. Available from: cera.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/ Hospital-Referral-Flowsheet.pdf

8. Dutch MJ, Denahy AF. Distribution of potential eye and tissue donors within an Australian teaching hospital. Cell and Tissue Banking. 2017 11 December;19(3):323–31.

9. Professional training [Internet]. DonateLife. Available from: donatelife.gov.au/forhealthcare-workers/professional-training

10. Philpot SJ, Aranha S, Pilcher DV, Bailey M. Randomised, Double Blind, Controlled Trial of the Provision of Information about the Benefits of Organ Donation during a Family Donation Conversation. Herrero JI, editor. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2016 Jun 20 [cited 2019 Dec 5];11(6):e0155778. Available from: ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pmc/articles/PMC4913899/

11. 2020 Australian Donation and Transplantation Activity Report 2020 Australian Donation and Transplantation Activity Report [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: donatelife.gov.au/sites/ default/files/2021-05/2020_australian_ donation_and_transplantation_activity_ report.pdf

12. Ahmed O, Brockmeier D, Lee K, Chapman WC, Doyle MB. Organ Donation during the Covid 19 pandemic. American Journal of Transplantation. 2020 13 July.

13. Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Krouse J, Howard RJ. Family initiated discussions about organ donation at the time of death. Clinical Transplantation. 2010 Jul;24(4):493–9.

14. Ting DSJ, Potts J, Jones M, Lawther T, Armitage WJ, Figueiredo FC. Impact of telephone consent and potential for eye donation in the UK: the Newcastle Eye Centre study. Eye (London, England) [Internet]. 2016 Mar 1 [cited 2020 Oct 29];30(3):342–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26514245/

15. Community resource library [Internet]. DonateLife. Available from: donatelife.gov.au/ get-involved/community-resource-library

16. Heckemann B, Hahn S, Halfens RJG, Richter D, Schols JMGA. Patient and visitor aggression in health care: A survey exploring organisational safety culture and team efficacy. Journal of Nursing Management. 2019 29 May;27(5):1039–46.

CLINICAL UPDATE Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 19

SAVE our planet PROTECT our health

THE CLIMATE CRISIS IS HERE. BUT THERE IS STILL TIME TO AVERT DISASTER IF WE TAKE ACTION NOW

The climate crisis predicted to happen sometime in the future has arrived. The fallout is evident, with poorer health, and wellbeing outcomes and environmental changes that sustains life. Science informs us if we continue along this trajectory, the impacts will get worse.

We can still mitigate climate change through sustainable practices which will reduce the burden on healthcare, and ensure a healthy plant.

Nurses and midwives, can be key players in change and make a significant difference by influencing the community to a more sustainable way of living.

The ANMJ wants to help all nurses and midwives achieve this goal for a sustainable future.

GLOBAL WARMING: HEALTH IS AT RISK BUT IS HEALTHCARE CONTRIBUTING TO THE PROBLEM?

Human-induced climate change is the most significant, most pervasive threat to the natural environment and societies the world has ever experienced, according to a report to the General Assembly in October last year. “The overall effect of inadequate actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is creating a human rights catastrophe, and the costs of these climate change related disasters are enormous,” says Ian Fry, Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change in the report.

To date, the planet has warmed more than 1.2°C compared with pre-industrial levels, resulting in profound and rapidly worsening health effects on every continent.1

IMPACT ON HEALTH AND HEALTHCARE

Planet warming is resulting in worsening health effects, health risks and the distribution of many infectious diseases. Heatwaves, for example, resulted in at least 350 deaths alone between 2000 and 2018 in Australia. As heatwaves increase in frequency and intensity more deaths are likely, with projected trends suggesting a potential increase of 10–50 additional heatwave days by the end of this century.2

Other extremes, such as fire, flood or drought, as well as high levels of pollution, can affect food security and access to supplies, including those necessary in healthcare.

Additionally, pollutants can be responsible for respiratory problems such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), asthma, bronchiolitis, lung cancer, cardiovascular events, central nervous system dysfunctions, and cutaneous diseases.1

WHAT IS GLOBAL WARMING

The United Nations, state global warming is caused by greenhouse gas emissions blanketing Earth. The gases trap the sun’s heat and holds it in the atmosphere, creating a greenhouse effect. As the world is warming faster than at any point in recorded history, warmer temperatures are changing weather patterns and disrupting the normal balance of nature over time.

20 Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 ENVIRONMENT & HEALTHCARE

THE CAUSES

It’s widely known that electricity and heat production, agriculture, forestry, other land use, transportation and buildings are leading contributors through burning fossil fuels such as gas, petrol, oil, and coal to gases. Collectively they add an additional 9.1 billion tonnes of carbon to the air each year.3

Not so well known is that healthcare makes up 7% of Australia’s total emissions4 and globally 4.4% of emissions 5

Researchers say the most significant culprits of healthcare emissions are hospitals and the pharmaceutical industry, making up two-thirds of the carbon footprint.4 Ninety percent of the carbon footprint stems from indirect CO2 emissions due to purchases between multiple economic sectors that feed into the healthcare sector. The healthcare industry also produces millions of tonnes of waste, ending in landfills and adding to the carbon emissions in the atmosphere.3

As climate change progressively impacts the determinants of health, community and social structures, so too does the pressure on already burdened health services. As healthcare itself contributes to the collective carbon footprint, this sits at odds with the mission of healthcare professionals to increase the duration and quality of patients’ lives.4

Maiek et al.4 says for healthcare to reduce its carbon footprint there needs to be carbonefficient procedures, including greater public health measures, to lower the impact of healthcare services on the environment.

GOVERNMENT’S RESPONSE

Until recently, there had been little momentum on reducing healthcare emissions despite Australia’s peak Climate and Health Alliance (CAHA) strongly advocating for government action on sustainable healthcare. Since the Albanese Government took power in 2022, there have been promising signs of a shift.

According to CAHA, this includes the Government committing to Australia’s firstever national plan on climate and health and working towards sustainable healthcare with state and territory governments.

Additionally, Health Minister Mark Butler confirmed climate change as a health priority for the first time in the Australian Parliament. There are also moves to address our plastic pandemic.

CAN NURSES AND MIDWIVES INFLUENCE CHANGE?

“Absolutely,” says Ros Morgan, ANMF’s (Vic Branch) Environmental Health Officer. Ros argues it’s crucial nurses and midwives

work towards reducing the adverse health and environmental impact of climate change and the sustainability of the healthcare system.

“Taking action will improve healthcare delivery and generate cost savings,” says Ros.

Nurses and midwives represent a large proportion of the healthcare workforce and are positioned as spokespeople and advocates.

“We are trusted, visible and connected with community. Nurses and midwives can be effective bearers of the ethical story and immediate context of climate change impacts.”

As individuals, Ros says nurses and midwives can lead by example, reducing emissions in their personal and professional lives.

“The things that we do as individuals add up and can lead to changed expectation, demand and cultural shift. Ultimately, we can be part of system change.”

Ros stresses business as usual is not good enough as it gives us a trajectory well beyond what is liveable.

“Direct patient care is a valued part of our role, but we also contribute to best practice, quality improvement and system performance. We are the experts in our own area. We see the waste, the loss, and the opportunities. We are integral to consultative process and in delivering improved outcomes.”

*Read this story at anmj.org.au to view references

THE FACTS

Healthcare makes up 7% of Australia’s total emissions

Hospitals and the pharmaceutical industry make up twothirds of healthcare’s carbon footprint

90% of healthcare’s carbon footprint stems from indirect CO2 emissions from purchases between multiple economic sectors that feed into the sector.

The healthcare industry produces millions of tonnes of waste, ending in landfills and adding to the carbon emissions in the atmosphere.

NEXT ISSUE

Find out why hospitals and healthcare create green gas emissions and how you can be the change to save healthcare and the planet

Learn more and get involved

The Climate and Health Alliance are made up of 100+ health sector organisations and 200+ individuals leading action on climate to protect our health. They provide resources and advocacy on climate. caha.org.au

ANMF (Vic Branch) provide resources on their website. They also provide CPD and courses designed to strengthen advocacy and leadership around climate mitigation and environmentally sustainable workplace practice. The Branch runs an annual health and sustainability conference and has a green nurses and midwives facebook page that anyone can join. While information is directed to Victorian nurses and midwives, much of the content can be applied in other states and territories. For more information go to: anmfvic.asn.au/

HealthEnvironmentalSustainability

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare has drafted a Sustainable Healthcare Module that is undergoing public consultation. Have your say what’s important to you. safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/ nsqhs-standards/sustainable-healthcare-module

& HEALTHCARE Jan–Mar 2023 Volume 27, No. 10 21

ENVIRONMENT

Sustainability in health champion

Meet OR nurse Sarina Henderson, a dedicated advocate for sustainable environmental practices at her work place at Melbourne’s St Vincent’s Hospital.

Sarina believes that nurses and midwives as healthcare professionals have a responsibility not only for the immediate care of their patients but also their future through protecting the planet of environmental impacts that affect health.

Sarina says one way nurses and midwives can do their bit is through recycling.

“Recycling can and does impact climate change by reducing the amounts going to landfill will therefore reduce emissions.”

Sarina has established a recycling bin in her staffroom, the collection of rigid plastic in the theatres and the collection of diathermy cables.

“Our recycling streams include paper, cardboard, rigid plastic, PVC, kimguard, aluminium, diathermy cables, batteries, polystyrene, and little blue towels (sterile cloth towels that come with sterile gowns to dry hands on).

“We also have a recycling bin in our staffroom and collect bottle lids, oral medication blister packs and stationery (pens and markers).”

Sarina says interest in sustainability in the department is spreading.

“There are now staff volunteering to help dispose of products at recycling collection points outside the workplace.”

She also has other staff members helping her with spreading the recycling message and finding ways to reduce and reuse supplies and equipment.

The team have come up with innovative ways to constantly remind staff to think about waste and the impact it has on the environment.