Category Archives: adventure

12 Best Places in China to Visit

The amazing places in China are practically endless. China is a vast country with distinctive regions, culture, food, and even languages. You could travel for a lifetime and never run out of fun things to do in China.

For me, it hasn’t been nearly a lifetime, but I did live in China for three and a half years, from 2020-2023. (During the pandemic, yes, but that’s another story.)

I spent more than six months of that time traveling, and I was fortunate enough to explore many fascinating places in China.

Besides week-long stops in cities like Beijing and Hong Kong, I took three extended, multi-month trips: one in Yunnan Province, one in Sichuan Province, and another, my first, to a bunch of different destinations in China.

- The Best Places in China to Visit

- 1. Beijing

- 2. The Great Wall of China

- 3. Xian

- 4. Xingping (near Yangshuo)

- 5. Zhangjiajie

- 6. Hong Kong

- 7. Macau

- 8. Guangzhou

- 9. Kaiping

- 10. Shanghai

- 11. Yunnan

- 12. Sichuan

- How to Plan a Trip to China

- Where to Stay in China

- Best China Tours

- Suggested China Itineraries

The Best Places in China to Visit

With so many spectacular places in China to visit, it can be hard to decide where to go. Nature or culture? Big cities or small towns?

This list of the best places in China are my favorites from my 3 1/2 years of living and traveling in the country.

I visited all of these places in China myself. I walked the streets, got lost, and found cool things I’ve never seen in other articles online. All the photos in this article are mine.

I recommend some tours in China, which are a good option for saving time and avoiding hassles. Although all of these places in China can be experienced on your own, and traveling in China is mostly easy, taking a China tour can show you aspects of the country you may never see otherwise.

Because I lived in China during the pandemic, this list lacks some other popular places in China. Remote and exotic Tibet and Xinjiang were closed to foreigners the entire time I was living in China. Others, like Huangshan and Xiamen, I wanted to check out but never ended up getting to. Maybe some day.

If you have any questions about how to travel to China, see the sections at the end, or leave me a message in the comments.

1. Beijing

Beijing deserves all of its praise. The city is home to the richest repository of Han Chinese culture, China’s dominant ethnicity, which comprises 92% of the population.

Not merely the political and cultural center of the country, Beijing is also responsible for the common language. Potonghua, the standard language of China that’s used nationwide, is actually the Beijing dialect of Mandarin, brought to official status during the Republican Era of the early 20th century.

Beijing is a massive metropolis containing some of the most important historical sites in the country, but it never feels overwhelmingly big. Instead of crowded skyscrapers, the center of town is occupied by two mostly open-air attractions: Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City, one of the largest palaces in the world.

- See the main Beijing attractions on this highly-rated and affordable private China walking tour: Tian’anmen Square and Forbidden City Walking Tour

Both are huge but quite spacious, and they’re surrounded by museums and walkable neighborhoods, with the modern central business district a short metro or Didi ride away.

Beijing is also renowned for its old neighborhoods based around alleyways called hutong. Although many got torn down in the previous decades, they’re still all over the city, including right next to the Forbidden City on several sides.

Some hutong are touristy, like Nanluoguxiang, and some are hip, like Wudaoying, but chances are there will be an everyday hutong located within walking distance of your hotel. With no souvenir shops or coffeehouses, just real-life residences, those hutong are really fun to stroll around — put away the smartphone and camera, and simply wander.

- A great way to experience the hutong of Beijing is on a China tour with a tuk tuk: Beijing Hutong Food and Beer Tour by Tuk Tuk

In case you’re wondering, Beijing and nearly everywhere else in China is extremely safe, with street muggings effectively nonexistent.

Finally, when talking about Beijing, you can’t forget the food. Not only do you have local cuisine, with Beijing duck and innumerable other dishes, but there’s also delicious food from all over China available in many different kinds of restaurants in Beijing.

The Great Wall passes by Beijing to the north, and several sections of the wall are within easy day-trip distance. When you visit Beijing, you’ll visit the Great Wall too.

2. The Great Wall of China

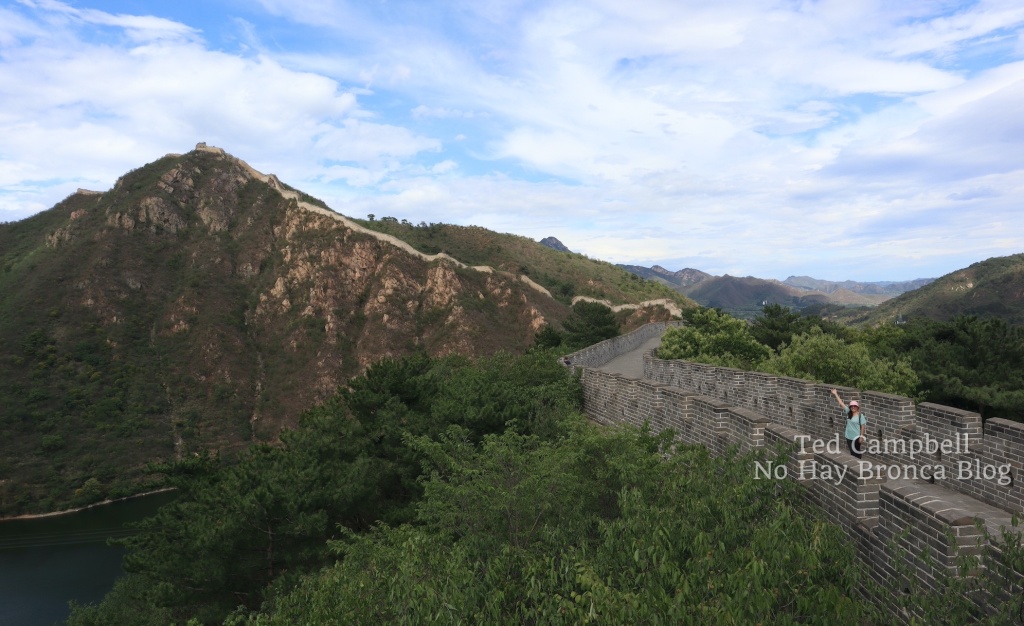

The Great Wall of China is more than a wall — it’s a wall passing through dramatic mountain scenery, sometimes hanging off the edge of cliffs.

It’s not enough to merely glimpse the wall rising and falling over this rugged scenery — you get to walk on it too. And if you’re not up for walking, you can take a cable car in the Badaling and Mutianyu sections of the wall.

In Chinese, the Great Wall of China is the Long Wall, a name recently adopted to cover the entire structure, which was previously known by many different names.

It’s not one contiguous structure at all, but a series of many walls. In some places in China, there are three different walls, all lined up in a row.

Therefore, there are many places in China to see the Great Wall. Most travelers go to one of the major restored parts near Beijing: Badaling, Mutianyu, Jinshanling and Simatai.

Years ago I went to Badaling, one of the most developed sections of the Great Wall of China. It was a nice experience, but when I returned I wanted to go to a less popular spot.

Before my last trip to Beijing, a friend recommended Huanghuacheng, which is often called the Water Wall. A large reservoir lies under the wall, and at several points the wall goes into it and under water. You can walk on the wall or on a trail along the reservoirs, and you may have it all to yourself.

We stayed the night before and after our day at the Great Wall in a nice guesthouse in the peaceful village outside the park. The wild, unrestored parts of Huanghuacheng are no longer accessible, but it’s still a great place to spend a full day exploring.

If you don’t have the time to spend several days getting to the Great Wall of China, you can save time and planning by taking a tour from Beijing. Here are some well-reviewed Great Wall tours. All you have to do is choose the section you prefer.

- Mutianyu Great Wall Bus Transfer with Options: Not a tour, but a hassle-free bus transfer taking you to one of the prettier parts of the wall.

- Private Mutianyu Great Wall Trip with English-Speaking Driver: Also takes you to Mutianyu, this time with private transportation.

- Private Great Wall Hiking Tour: Across The Border of 3 China Provinces: Hikers who visit China will want to check out this Great Wall tour, which includes a 3-4 hour hike at the Sanjiebei section of the Great Wall.

- Wild Great Wall Huanghuacheng Half Day Tour: This China tour from Beijing takes you to the section of wall I most recently visited. If you don’t have three days to spare going there on your own, then this is an excellent choice.

3. Xian

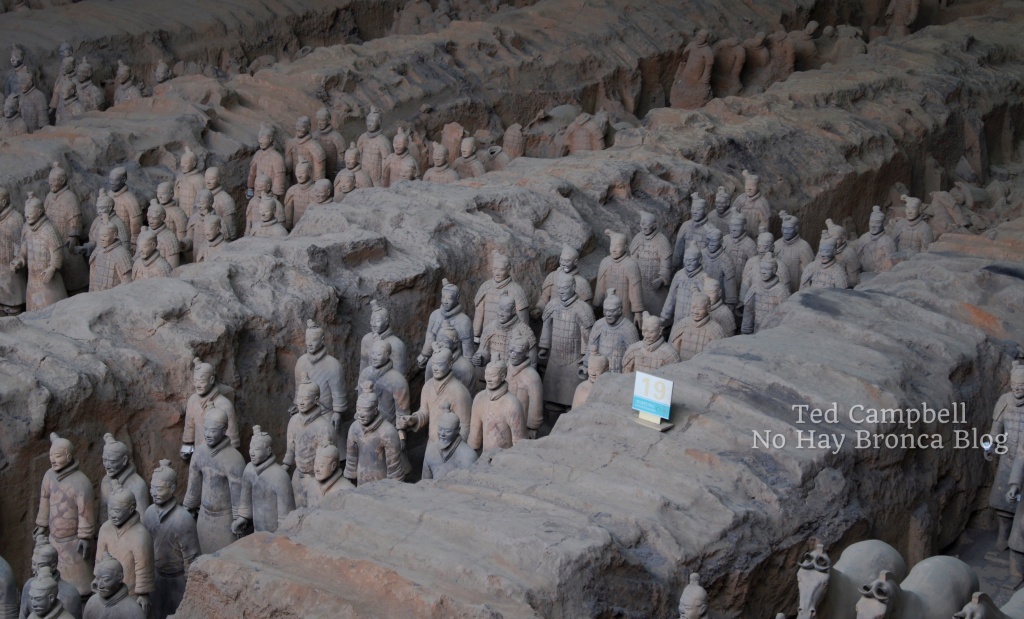

Located in north-central China, Xian (officially written as Xi’an) is best known for the Terracotta Warriors, a 2000+ year-old army of more than 8000 life-sized sculptures of soldiers, horses, and chariots. This monumental discovery was only made in 1974 and excavations are ongoing.

But there’s so much more to experience in Xian, a charming, easily-navigable mid-sized Chinese city. In 202 BC, Xian became the capital of the first dynasty of imperial China, and it’s played an important role in Chinese history and culture ever since.

Along with seeing the Terracotta Warriors, one of the best things to do in Xian is to walk the entire city wall. This 14-km trek through gates and past watchtowers gives sweeping views of the city, with dense traditional neighborhoods, leafy parks, large temple complexes, and remnants of the old city moat below.

Xian has some of the best food in China as well. The city has a large Muslim district, and in it you’ll find busy local restaurants serving local cuisine such as spicy noodles, lamb soup with pita crumbled in, and rojiamo, the Chinese hamburger.

- Explore this fascinating Xian neighborhood when you visit China on a Xi’an Muslim Quarter Night Market Foodie Walking Tour.

In Xian, come for the Terracotta Warriors, and stay for everything else. I spent over a week there and didn’t exhaust all the possibilities of what to do in Xian.

- Many China tours go to the Terracotta Warriors. This is the best one I could find: Customized Private Day Tour of Terracotta Warriors and Xi’an

4. Xingping (near Yangshuo)

China has some of the most striking mountain ranges imaginable, and the tall, rounded, steep karst mountains of Guangxi Province in southern China are some of the most iconic.

Guilin, the largest city in the area, is best known to the Chinese, while most foreigners think of the nearby town of Yangshuo first. Both are fantastic, although Yangshuo is probably a better choice for most international travelers.

The peaks in Yangshuo are denser and closer to town, and it’s also easier to get to the Yulong River, a stunning spot for a boat, bicycle, or motorbike ride through the mountains.

- Get to the best areas for cycling in Yangshuo without getting lost on this bicycle tour: Private Bike Tour: Yangshuo Countryside

Although it used to be this way, don’t expect a laid-back backpacker’s paradise in Yangshuo anymore: It’s now quite busy and firmly devoted to domestic Chinese tourism, though not nearly to the extent of Guilin.

Xingping, a small town on the Li River between Guilin and Yangshuo, is by far my favorite place in the area. It’s definitely touristy, but it’s also much smaller and is an ancient town full of historic buildings.

The view from the river in Xingping is so lovely that it’s even been featured on the RMB 20 bill.

If you like hiking, then Xingping is definitely your spot, with three good trails that go up into the mountains and a long walking path by the river. You also can hike or take a boat to Yucun, the next village over, and hear the story of how Bill Clinton and family dropped by in 1998.

In Xingping, it’s easy to get information about hikes in the area from any hotel. There are plenty of places to stay, including hostels with an international vibe (rare in China) and this really nice guesthouse, where I stayed for an extended visit in 2020.

Finally, another great thing about Xingping is how easy it is to get to. The Yangshuo high-speed railway station is right next to Xingping, while the town of Yangshuo is actually about an hour farther down the road.

- If you do go to Guilin, you can see all the sights on this China tour, which includes Reed Flute Cave, Xianggong Hill, and a Li River cruise: Guilin: Classic Private Full–Day Tour

I want to make a special mention of the Longji Rice Terraces, which are close to Guilin, in the opposite direction of Yangshuo. With slope after slope of rice terraces in every direction, they’re one of the most beautiful places in China I’ve seen. You can stay in a small guesthouse and hike all around them.

- If you don’t want to get hopelessly confused taking public transportation to Longji (like I did) when you travel in China, you can check out this Longji Rice Terraces & Minority Villages Private Day Tour

5. Zhangjiajie

Speaking of cool mountains, Zhangjiajie in the central province of Hunan should be at the top of every nature lover’s list of where to go in China.

Commonly known as Zhangjiajie (the name of the nearest city), Wulingyuan National Park has the kind of otherworldly, jaw-dropping scenery that could only exist in China.

Best known for valleys of tall, precariously-balanced stone pillars, Zhangjiajie also has dense jungle full of monkeys and giant salamanders.

The park has several cable cars and a super-high elevator, but it’s covered in trails too, making it great for hiking. The cable cars and elevator draw most of the tourists, so you may have the trails all to yourself.

The entry ticket for Zhangiajie is for three days, and you’ll need all three to fully appreciate the park. That’s how big it is.

In China and elsewhere in Asia (Angkor Wat for instance), multi-day tickets mean there’s enough in the park to justify spending each day there. Unless you’re really pressed for time, it would be a shame to only spend one day in Zhangjiajie.

Also, three days means insurance against bad weather. It was so cloudy on my first day in Zhangjiajie that I couldn’t see anything from the lookouts. I can’t imagine how disappointing it would have been to leave the following day.

Don’t limit your time to only three days, though. Down the road from Wulingyuan National Park, Tianmen Mountain is bulky mass of cliffs crossed by hiking trails and glass-bottom skywalks.

The name Tianmen, “Heaven’s Gate,” refers to a large natural arch with the 999-step Chinese Stairway to Heaven below. I suggest you walk down the stairs, not up them.

- You don’t need a tour for Zhangjiajie unless you’re pressed for time when you visit China. In that case, you’ll want to make the most of it. This China tour isn’t cheap, but it covers everything you need to see in Zhangjiajie (and includes all entrance tickets): Private Trip of Zhangjiajie National Park and Glass Bridge

6. Hong Kong

Hong Kong isn’t only one of the best cities in China, but one of the best cities in the world. Where else can you take a boat trip to an island, climb a mountain, eat first rate Cantonese food, and see a Black Sabbath cover band, all in the same day?

You must cross a border to go to mainland China from Hong Kong, and it has a different currency, but Hong Kong is officially part of China, which is why it’s on my list of best places in China to visit (along with Macau).

I can’t say enough good things about Hong Kong. Its multicultural vibe and wide variety of neighborhoods and landscapes make it unlike anywhere else in China.

And, making it even better, Hong Kong is a great place to look for international flights for flying to China. Coming from North America or Europe, you might find that a flight to Hong Kong is a lot cheaper than direct to a mainland city like Beijing or Shanghai.

As a worldwide tourist hub, Hong Kong has all kinds of interesting tours available. Here are some of the cooler Hong Kong tours I found:

- Enjoy a light show from Victoria Harbour on the Victoria Harbour Night or Symphony of Lights Cruise

- Experience the best of Hong Kong — sightseeing, food, history — with this popular Hong Kong Tour – Landmarks Visit

- Looking for something different from a Hong Kong tour? Check out this Dark Side of Hong Kong Walking Tour

7. Macau

Macau is close to Hong Kong, just across the Pearl River Estuary, and it has a similar colonial history. But it’s a mistake to assume these two cities are anything alike.

For one, Macau is much smaller. Confined to two smallish islands, which were once several more until extensive land reclamation projects combined them, Macau is easy to navigate and get around.

Until you begin exploring the Historic Centre of Macau, that is. Macau’s old downtown core is a maze of twisting streets and narrow alleyways, somehow all leading to the hilltop Ruins of Saint Paul’s, the facade of a 17th-century church which includes Chinese characters, guardian lions, and other Asian touches.

Most of the buildings in central Macau are mid-century Chinese-style apartment buildings with decaying metal-bar “pigeon cage” porches built impossibly close to one another. But then, you turn a corner and suddenly see a stately old building from the colonial Portuguese days.

All this means that Macau is great for walking, and when you get tired of the urban labyrinth, you can head out to Taipa and Coloane on the larger southern island for charming fishing villages, nice hiking trails and a few sandy beaches.

And don’t forget the casinos. Built on a flat expanse of reclaimed land, these huge structures rival Las Vegas in size and audacity (gondolas on a system of indoor canals in the Venetian, a full-size Big Ben outside the Londoner, etc.)

It’s Vegas without the party, though, and 90% of the tables are baccarat, with very few for blackjack, poker, or roulette. Table minimums are really high, too. Therefore, most ordinary tourists will probably prefer Macau’s less risky delights.

- It’s easy to visit Macau from Hong Kong, and if you want to maximize your time and minimize your planning, you can do so on this One-Day Macau City Tour from Hong Kong

8. Guangzhou

As much as I love historic Beijing and dynamic Hong Kong, Guangzhou is my favorite city in China.

Guangzhou is Canton, so it’s ground zero for all things Cantonese: culture, language, and of course food.

I lived in Guangzhou for six months and spent a lot of time exploring the city. It’s a sprawling megalopolis home to many unique neighborhoods, all very walkable.

Three large neighborhoods are chief among them: ultra-modern Tianhe, bustling central Yuexiu, and well-restored, traditional Liwan.

It takes at least a day to properly see each, meaning Guangzhou is three (or more) cities in one. Add in all the other surrounding attractions, and you could easily spend a week in Guangzhou and have plenty left for your next visit.

- A night cruise on the Pearl River is one of the top things to do in Guangzhou. Book it here with this Guangzhou tour: Pearl River Night Cruise with Private Transfers in Guangzhou

Guangzhou has a good location too, about an hour (by subway and high-speed train) from Shenzhen, which in turn is on the border with Hong Kong. City lovers could make an excellent China trip of exploring Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou in a week or longer.

Actually, if you can stand to miss the top attractions in China — Beijing, the Terracotta Warriors, and the panda reserves — an excellent alternative itinerary for hitting some of the best places in China would be to take the high-speed train from Hong Kong to Guangzhou and then onward to Xingping (Yangshuo), #3 on this list of places in China to visit.

And while in Guangzhou, if you have time, take a side trip to…

9. Kaiping

About an hour south of Guangzhou is Kaiping, one of the lesser-known places in China to visit.

The top Kaiping attraction is the Diaolou, early 20th-century homes built by returning overseas Chinese. Most are blocky, fortified towers with beautiful ornamentation inside and out.

The history of how these came to be is too complicated to get into here, but know that visiting the Kaiping Diaolou involves learning a lot about the interesting, turbulent history of modern China.

Thanks to a free bus connecting several villages of Diaolou in the suburbs of Kaiping, visiting them is easy. And because most Diaolou are still functioning residences, and many are adjacent to ancient rural villages, this trip also serves as a glimpse into life in rural China. (There’s no website for the bus — just show up at one of the villages and you’ll find it.)

Kaiping itself is a small-sized everyday Chinese city, but to me, that’s part of its appeal. It’s a prosaic and gritty view of the country you’d never get if you confined your China trip to only Hong Kong or Guangzhou.

For a cinematic look at the Kaiping Diaolou, check out the excellent and supremely-popular Chinese action/comedy/Western Let the Bullets Fly, which was filmed in the area.

- Don’t have three days to experience Kaiping while you visit China? You can get there and back in one day with this well-reviewed China tour from Guangzhou: Kaiping Private Day Tour From Guangzhou

10. Shanghai

China’s second city doesn’t quite have the concentration of history and culture that Beijing has, but Shanghai is undoubtably an excellent destination in its own right.

Although it’s second to Beijing in terms of cultural, political, and historical significance, Shanghai is China’s largest city — by a lot. At about 22 million, its population is nearly twice that of Beijing, the second most populous in the country.

Central Shanghai is cut in half by the wide Huangpu River. One side has the Bund, an elevated path along the river, with large colonial era buildings behind it. Behind the Bund are broad shopping streets and block after block of the singular Shanghai-style shikumen communal housing.

Farther on are other novel Shanghai neighborhoods to wander around, such as the faithfully-recreated old-China pedestrian streets surrounding Yu Garden and the historic French Concession.

- Visit all the best Shanghai neighborhoods on this Shanghai: 8-Hour Private City Tour

- More into food than sightseeing? When you travel to China, this Shanghai tour is for you: Shanghai: 3-Hour Local Food Tasting Tour

- Another great option is to explore Shanghai by bicycle: Shanghai Half-Day Bicycle City Tour

The other side of the Huangpu contains the structures of Shanghai’s instantly-recognizable skyline, including the Oriental Pearl Tower and the Shanghai Tower, the third tallest building in the world. Naturally both have an observation deck for you to ascend.

Getting out of the city center is also rewarding in Shanghai. Yes, there’s Shanghai Disneyland, but there are also numerous water towns to choose from as well.

Water towns are old communities built around canals, and there are more than a dozen noteworthy ones around Shanghai.

A great choice for a day trip from Shanghai is Suzhou, which besides the canals and narrow alleyways of a water town is home to some of the most famous classical gardens in all of China.

- See Suzhou and a water town on this popular day trip from Shanghai: Su Zhou and Zhou Zhuang Water Village Day Tour

11. Yunnan

For my final two best places to go in China, I’m putting in whole provinces.

I spent about six weeks each in Yunnan and Sichuan on separate trips. If you’re looking for some real adventure in China and have longer than a month to travel, I suggest flying into a major city and then heading right to one of these provinces.

Located at the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, Yunnan and Sichuan are so jam-packed with natural beauty and history — sometimes both in one destination — that I’d quadruple the length of this article if I included them individually.

So, instead, I’ll list some of the top destinations in Yunnan and Sichuan to explore when you travel to China. Some of the best places to visit in Yunnan are:

- Kunming: On the shore of a large lake, the capital of Yunnan Province has historic neighborhoods and a fantastic mountainous area, Xishan, with trails and temples carved into cliffs.

- Shilin (Stone Forest): Near Kunming is this bizarre landscape unlike anywhere else in China, although similar landforms do exist in other parts of the world. Many people see it on a day trip from Kunming, but you could stay a night or two in order to have more time in the park and surrounding areas.

- Dali: It’s a beautiful ancient town next to a big lake with a tall snowy mountain backdrop behind. There are great hikes in the mountains and nice walks along the lake.

- Lijiang: Possibly the prettiest and most interesting ancient town in China, Lijiang is a maze of winding cobblestone streets and well-restored courtyard houses.

- Tiger Leaping Gorge: Near Lijiang, the Tiger Leaping Gorge is where the Jinsha River runs behind the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain. The best way to experience it is with a two-day hike on the upper trail.

- Shangri-La: A few hours north of Lijiang and Tiger Leaping Gorge is the town of Shangri-La. The old Tibetan town was mostly destroyed by a fire is 2014, but it’s been so tastefully restored that you’ll never notice. Some buildings were spared by the fire, including this traditional guesthouse, one of my favorite places to stay in China. While in Shangri-La, don’t miss the massive Ganden Sumtsenling Monastery, the closest you’ll get to the Potala Palace if you can’t make it to actual Tibet.

- Xishuangbanna: Near the Laos and Myanmar borders, Xishuangbanna is Southeast Asia with Chinese characteristics. In town, enjoy the expansive night market; outside of town, choose from a hilltop Buddhist temple, big botanical gardens, and a wild elephant sanctuary.

There’s a lot more to see in the province; these are the major destinations in Yunnan. As I mentioned, check back on this blog for a complete article about travel in Yunnan.

12. Sichuan

Yunnan and Sichuan both have incredible natural areas and lots of culture.

I spent about six weeks traveling in each, and I got the impression that Yunnan is much more traveled by international visitors than Sichuan. There was far less English spoken (and written) in Sichuan, and my wife and I were stared and pointed at by locals more often in Sichuan than in Yunnan.

Traveling in Sichuan was a little more challenging, but as with all places in China, it’s not really that difficult.

Some of the best places in Sichuan are:

- Chengdu: Sichuan’s capital city has well-restored ancient towns, busy city-center outdoor shopping districts, world-class museums, and some of the best food in China. And don’t miss the fabulous Sichuan Opera.

- Panda reserves: Start with the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, which has hundreds of giant pandas and red pandas. Then, venture into the countryside for other reserves, such as the Dujiangyan Panda Base, called Panda Paradise in Chinese.

- Dujiangyan: It’s a large, charming ancient town next to one of the world’s oldest irrigation systems. Close by are two excellent hikes on Qingchen and Qingchen Hou mountains.

- Siguniangshan: In cultural Tibet, you can hike to the foot of 6,250-meter (20,000-foot) Mount Siguniang or though the forest valley below.

- Jiuzhaigou National Park: This is one of the most beautiful national parks in China, and not for the mountains (which are pretty), but for the multicolored lakes and terraced waterfalls between them. One day is not enough to fully take in Jiuzhaigou.

- Leshan: Surrounded by ancient temples, the 233-foot, 6th-century Leshan Giant Buddha gazes over a lazy river from his cliffside seat.

- Emeishan: You have many hikes to choose from on this large sacred mountain, including a two-day trek from the bottom to the top, staying the night in a Buddhist temple on the way.

- Bamboo seas: There are several large bamboo forests in Sichuan province. I visited one right outside of Chongqing called Tea Mountain, named for the tea plantations outside the bamboo.

Chongqing isn’t part of Sichuan Province anymore, though it used to be, and it’s easy to get to by high-speed train from Chengdu.

Built over the high banks of the confluence of the Yangtze and Jialing rivers, Chongqing is part ordinary Chinese big city and part city from a parallel universe, where subway trains pass through apartment buildings and timeworn caves converted to tourist complexes resemble the bathhouse in Spirited Away.

Simply put, yes, Chongqing is worth a stop when you visit China.

Please check back on this blog for a complete article about traveling in Sichuan.

How to Plan a Trip to China

After you’ve considered the many places that you’d like to visit, the next step is to make a definite plan to travel to China.

First, think about flying to China. I suggest looking for international flights to Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Check the prices and connections. You may want to fly into one city and out of another.

From those cities, you can fly to anywhere else in China. You can also take the train to just about anywhere as well, but if it’s far away, flying might be cheaper. Check both as you plan your China trip.

One of the best resources for finding flights (and hotels, trains, and more) in China is trip.com. You can also fly to China by checking booking.com.

You can use trip.com for trains in China, but they charge a small fee, which will add up if you’re doing a lot of train travel.

The Chinese website for buying train tickets directly is 12306.cn. After your first purchase, you’ll have to go to a station ticket counter to confirm your identity, although there’s talk of this requirement being taken away. If this is too complicated, then just use trip.com for train travel in China.

Also necessary for traveling in China is the app Didi, the Chinese Uber.

Planes, trains and Didi: That’s about it. Unless you take a tour or go somewhere remote, you may never get on a bus in China.

Where to Stay in China

In my experience, the two best websites for finding hotels in China are trip.com and booking.com.

When I’m looking for hotels in China, I always check both. I find that trip.com usually has better options for China — it’s a Hong Kong company, after all — but sometimes I encounter a better deal on booking.

If you’re overwhelmed by all the accommodation options, you can rely on a few common hotel chains in China that are almost always cheap and clean. In multiple cities I’ve stayed in Lavande, Ibis, Campanile, and Holiday Inn Express and have never been let down.

Outside of major cities, some major higher-end chains, like Hyatt, might be surprisingly affordable, so check them too.

Note that hotels in China need special permission from the government to accept foreigners, and often the very cheapest hotels don’t have that permission. If you’re using trip.com or booking.com, don’t worry about it, because those apps won’t let you make the reservation as a foreigner anyway.

There aren’t many hostels in China, although you might find them in major cities. Airbnb does have a presence in China and is worth looking at for certain areas. If you can’t find a hotel you like, check airbnb.

Best China Tours

I don’t recommend you sign up for a tour for your whole time in China. Tour groups in China are notoriously large, noisy and rushed. They include very little free time and only go to the most popular destinations. It wouldn’t be fun to be stuck in one of these groups for your entire China vacation in a country that, despite some difficulties, is generally easy to travel in.

There are, however, two very good reasons to take a China tour: to save time and to avoid confusion. Also, tours in China can be very affordable and will almost always save you money.

I say, if you want to take a tour in China, take a day tour. The ones I recommend in this article all have good reviews and go to cool places.

Here are some of the more interesting China tours I found:

- Hike the Great Wall of China on this Private Great Wall Hiking Tour: Across The Border of 3 China Provinces

- See two of the top attractions in Sichuan on the Chengdu: Giant Panda Research Base & Leshan Buddha Day Tour

- Get up close with the pandas on this Dujiangyan Panda Volunteering Experience with Lunch

- Kunming: Stone Forest Private Day Tour: Get to the Stone Forest and back from Kunming easily on this Yunnan tour.

- This Jiuzhaigou tour is expensive, no doubt about it, but if you want to see what may be the most beautiful natural area in China (and Huanglong National Park too) in the most efficient and stress-free way possible, then check out this Private 4-Day Jiuzhaigou and Huanglong National Parks Tour from Chengdu

- 7 Days Lhasa to Kathmandu Overland Small Group Tour: This China tour gives you the complete Tibet experience in only one week.

Suggested China Itineraries

You’d need a minimum of six months to properly see every place on this list of best places in China. Assuming you have less time than that, at least a week and up to a month, I’ve created some possible itineraries for your China trip.

Because of the ease and relative low cost of air travel in China, you can really make any plan you want. You can fly to China and then fly to three or four different places in China in far away parts of the country for very reasonable prices.

If you’d like to keep things simple (and cheap) by visiting destinations in China that are close to each other, here are my suggestions:

- Best of China: Beijing and the Great Wall (1 week). With extra time, you could add a trip to Xian or Shanghai (2-3 weeks).

- Best of Southern China: Hong Kong and Guangzhou (1-2 weeks). With extra time (2-3 weeks), stop in Shenzhen on the way between them, and take in some beautiful natural areas using the high-speed train from Guangzhou north to Xingping and Yangshuo or south to Kaiping, Zhuhai and Macau.

- Mad Mountains in China: If you really love nature but only have about two weeks, this one’s for you. Travel to Zhangjiajie (1 week: 3 days for the park, plus a day in Tianmen Mountain and travel time between them) and Xingping/Yangshou (minimum 1 week). If you have a little more time, you can start and end your China vacation in a big city like Beijing or Hong Kong.

- Yunnan Adventure: Visit some or all of the places in Yunnan I listed above. You’ll need a month or longer to see them all. It took me six weeks.

- Sichuan Adventure: Like for Yunnan, look at the places in Sichuan and choose your favorites, basing your trip in Chengdu. This trip is a little harder than in Yunnan, since the destinations are more scattered about and it’s somewhat less traveled by foreigners than Yunnan.

Thanks for reading this article about my favorite places in China. Any questions, please write in the comments below, and check back for future articles that will go more in-depth about some of these wonderful places in China.

This page contains affiliate links, which means I earn a small commission if you purchase something after clicking a link on this site. I receive this commission at no additional cost to you.

Hiking an Underground River in Mexico

An underground river – I didn’t know such a thing existed. But ok, it made sense. A river underground, right? Want to hike it? Sure, why not?

I imagined a winding tube starting from a modest crack in the earth, like an old-time mine shaft cut through rock. I imagined crouching and crawling, like when my middle school buddies and I explored a city sewer. My friend Pedro, who invited me, said it would take about six hours. Alright, let’s do it.

I definitely didn’t imagine a fast-flowing, waist-deep stream entering a huge vertical hole wider than the tunnel for a two-lane mountain highway. I didn’t expect to spend more than eight hours underground, to finally emerge at sunset from an equally large hole on the other side of a mountain. And I didn’t expect that, before all of this, we’d hike for two hours and then climb down a steep canyon cliff on a flimsy steel staircase just to get to the cave entrance.

About 150 kilometers southwest of Mexico City in central Mexico, the Chontalcoatlán River begins on the high slopes of the inactive Nevado de Toluca volcano. It travels though parched, desolate highlands of thick shrubs, scraggly trees, and tall cactus.

Above ground, it looks like a typical mountain stream. Cold clear water flows over submerged boulders and rocks, twisting and turning at the bottom of a dry valley so deep that you’d never see it unless you peered down from a bridge.

This large region of the Sierra Madre del Sur mountain range is neither cool plateau nor steaming valley, but something in between, a subtropical land of sand, sandstone, and tiny communities of concrete and sweat. These are the hidden corners of Mexico, far from cities or even proper towns. These are the corners that hide underground rivers.

The word Chontalcoatlán is a mouthful, so it’s often abbreviated to La Chonta. It’s named after the Chontal tribe, one of the many indigenous groups of central Mexico with distinct customs and languages. Currently fewer than 200 native speakers of Chontal remain, most living far away in the southern state of Oaxaca.

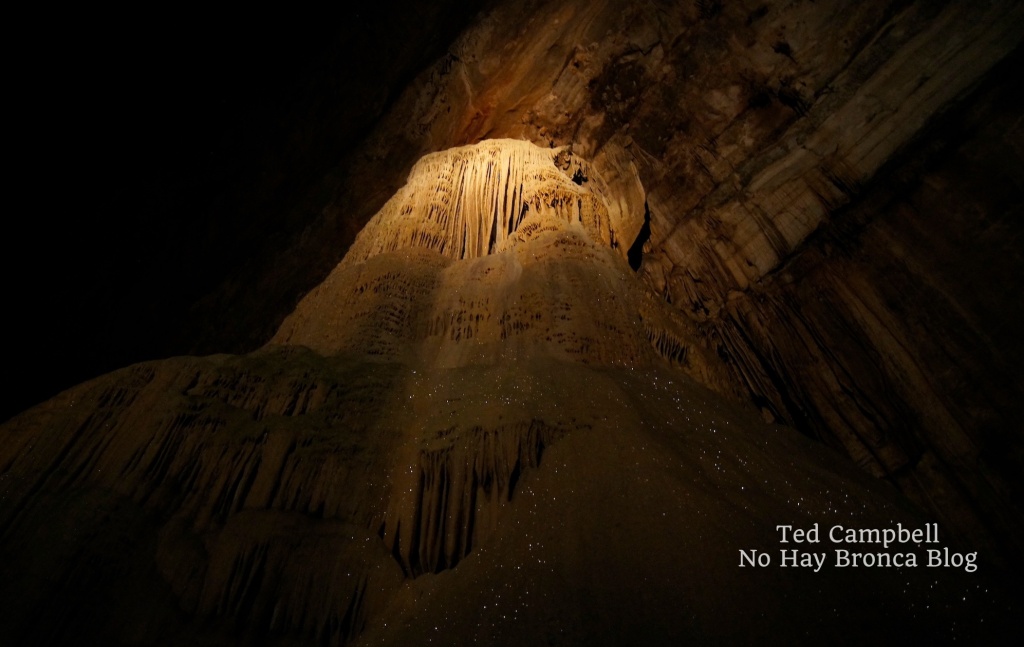

We began the adventure at the Grutas de Cacahuamilpa — the Cacahuamilpa Caves — a national park with chambers as big as soccer stadiums. A concrete footpath takes visitors deep underground into one of the largest cave systems in the world, so large and labyrinthine that native people hid in them after the Spanish conquest.

If you’d like to visit the Cacahuamilpa Caves in Mexico, you can take a cave tour from Mexico City, a cave tour from Taxco, or a cave tour from Acapulco.

Below the entrance to Cacahuamilpa’s cave passage is where the Chonta river exits the mountain, returning to daylight. At this same point another underground river, San Jeronimo, flows out of an equally large hole and joins the Chonta to form the Amacuazac River. It then makes the long trip to the Pacific Ocean.

These two holes are called Dos Bocas (Two Mouths), and they’re easily reached by hiking down the valley from the entrance to the Cacahuamilpa Caves.

At 12 km, the hike through the underground portion of San Jeronimo is not only longer but also much more treacherous than the eight kilometers La Chonta spends below ground. San Jeronimo is for experts only. Pedro told me that some sections of the underground river have whirlpools that can suck you down into who-knows-what below, lifejacket and all.

Seven of us would hike La Chonta today: Pedro, three of his co-workers — our leader Carlos and two others — and Carlos’s teenage son and his son’s friend.

Pedro and a few of the others had done the hike before, but Carlos was our leader because he’d done the hike almost every year for the past 20 years. His first time was with a high school group.

After breakfast in the small market at the entrance to the Cacahuamilpa Caves National Park, Carlos hired a pickup truck to take us to the trailhead high in the mountains. We would exit the underground river at Dos Bocas right next to Cacahuamilpa, but first we’d need to get to the opening of the cave, by truck and then on foot. I knew the highway well, having ridden it on my bicycle many times, but I’d never noticed the small turnoff about 15 minutes by car from the caves.

We hiked for about two hours, first along a mountain ridge though a forest of leafless trees and shrubs. It was dry season — the reason we were going in February. The hike is impossible during the summer rainy season when the river and rapids are high.

Carlos and his friends chose early February to beat groups of students and boy scouts who leave their garbage inside, which the summer rains eventually wash away every year. At one point in the cave I saw a car tire stretched and jammed down to the bottom of a long, pointy piece of rock, a testament to how powerful the river is during rainy season.

I wore a swimming suit, a quick-dry t-shirt, a lifejacket, and stiff-soled hiking boots. I was glad for the boots many times that day, even though one of them eventually fell apart. A few people in our group had tennis shoes, and I often saw them wince as they bashed their feet on submerged rocks. Even with hiking boots, my feet and ankles were brutalized by the end of the day.

I also carried a small backpack that held two headlamps, two sandwiches, and a bottle of water. Slung to the backpack was an old bicycle helmet that I’d wear once in the cave.

We crossed the high ridge of the mountain range and began to descend. The trail got steeper as it curved downward, with large stones in the path among the sand. The trail entered the morning shade of the valley and suddenly the trees were full of green. Soon we were crawling over boulders and gripping branches for support. The trail ended at a cliff. A thick metal cord, lightly rusted with age, was bolted to a rock above the cliff.

Carlos climbed down first, disappearing below the rocky ledge. Then one by one we went down. I was the second to last. The metal cord held firm and there were plenty of footholds.

As I stepped down the cliff, Carlos came into view below. He wasn’t on the valley floor, but on a narrow ridge above another cliff. From here an old metal ladder began that was much longer than the cord. Halfway down it too went out of sight under the cliff.

The ladder shook and shifted as I climbed down it. A few rungs were missing, broken away. While placing hand below hand, foot below foot, I thought about Pedro above me, waiting until I got to the bottom before he started climbing down.

I thought about the large group we’d passed earlier on the trail. They’d climb down next, all ten or so of them, one after another. And after them more groups would come during the two or three months of continuing dry season.

They’d all make it down. The ladder would hold. And with that, I landed. My feet were firm on the rocky riverbank. For the first time I had a clear view of the humungous hole and thought, wow.

The opening to the underground river was a vertical crater rimmed in white with sheer cliffs above. You could see that, instead of continuing on between the mountains, the forces of water that had formed this deep valley — I’d call it a canyon or gorge if it weren’t so covered in shrubs and trees — hit a dead end here. Somehow the crater was hollowed out, sucking water into it like the drain on a locker room floor.

We sat under the high cliffs and had an early lunch before entering. The chamber at the opening was large as an airplane hanger, with calm water below that flowed into total darkness.

The shakiness I felt from climbing down the adder finally left me. I half-expected to jump right in the water and start floating downstream, but instead we walked on the sandy banks, climbing over boulders strewn about. It didn’t take long until the faint light from the big hole behind us finally disappeared and the only light was from our headlamps and flashlights.

When we came to impassable cliffs, we’d wade across the underground river to the other side, initially going no deeper than our thighs. The water was cold. When the current ran quickly, we’d all hold hands as we stumbled across.

Carlos was always in the lead, picking the best route. He told me later that nothing was as he remembered it. The two powerful earthquakes that shook central Mexico in the fall of 2017 had moved everything around.

(I finally got around to posting this story in 2023 but did this hike in 2018.)

The cavern walls and ceiling were covered with intricate limestone structures. Delicate ridges of sparkling mini-crystals dripped like melted cheese frozen to stone. False turns in stagnant pools of water had thick films of brown and green that released a rotten stench as we waded through them. We stopped at one point and turned off our flashlights. The darkness was complete—you couldn’t see your hands in front of your face.

After several hours of this we reached a chamber so big that the flashlight beams vanished overhead. We stood on a wide gravel beach. Next to the cavern wall was a foot-tall statue of the Virgin Mary in a metal cage, decorated with colorful plastic flowers and surrounded by the remains of burnt candles. The metal cage was deeply rusted and the statue was coated in black soot from the candles.

Nearby on the rock was a large plaque in recognition of one of the underground river’s early explorers, who’d recently died of old age, not in the cavern as I first assumed. By how worn it was, the plaque looked ancient, but it had been erected only five years earlier.

Carlos said there were interesting places to explore here. We walked across the gravel and scrambled up some boulders. We took off our lifejackets and backpacks, leaving them on the rocks. A rope hung down from a cliff. We took turns climbing up into the dark unknown.

At the top of the cliff was a flat platform of smooth stone. The ceiling was still far above and out of flashlight range, even though we’d already climbed higher than a two-story building. We walked around a corner to an area enclosed in high walls of jagged stone. Pointy, delicate stalactites hung from above. Carlos shone his headlamp down to where the cavern wall met the floor, into a hole no bigger than the opening of a washing machine.

“We can climb in there,” he said, getting on his knees. He adjusted his headlamp and crawled in headfirst, slithering like an iguana, his boots dangling behind as he pushed himself into the hole.

His son went next. Then me. The ground was heavy mud that protected my elbows and knees from the hard rock, although they were unavoidably scratched a few times. Occasionally I could lift my head and look around, but in most parts the rock was so close that my chin dipped into the mud below and my helmet banged against the rock above.

The tiny tunnel went up, then to the side, then down, then up again. One downward section was a steep slide headfirst into the mud. It was more open at the bottom, and I could get up on my knees. Carlos’s son sat there with the mud above his hips, eyes wide, breathing hard—clearly terrified.

“I’m going back,” he said. He called down the cave to his father, “I’m going back.” I couldn’t hear Carlos’s muffled reply. His son squeezed passed me and scrambled up the rock I’d just slid down.

That’s when I felt it—the closeness of the walls, the staleness of the air, the feeling of being utterly trapped and helpless. If I panicked, then I’d be truly trapped—there was no rushing out of this cave. The only way out was a slow, patient crawl through even tighter rock, following Carlos’s son. I took a deep breath of the muddy air, reminding myself that panic was the only enemy. Or another earthquake…

It was warm, at least. I wasn’t shivering for the first time since getting into the underground river hours ago. Calm, I told myself, be calm. At that moment Pedro came down the slide and splashed into the mud next to me.

“I’m going back,” I said. “Ok,” he replied. He squeezed past me toward Carlos deeper in the cave.

I looked at the soles of Pedro’s boots slipping out of sight, then in the other direction up the slide toward the exit, then back at the hole where Pedro’s boots had been. Ah, what the hell, I thought, and followed him.

We crawled about twice as deep again to another chamber, this one as spacious as the bathroom on a Greyhound bus. Carlos was waiting for us there. He pointed to where the cave continued on the high opposite side of the chamber. It would be the tightest squeeze yet.

“After about two hours, it reaches an underground lake,” Carlos said.

“You’ve been to the lake?” I asked.

“Sure, many times.” He pointed to a crude clay sculpture of a man with a large erect penis on one side of the chamber. “My friends made that the first time I came down here, when I was in high school.”

“Two hours?” I asked.

“Yes, about two hours. We can’t go now, not enough time. We can do it next time.”

“Two hours in a tunnel like this one we just went through?”

“Most of it’s even smaller,” he answered.

An underground lake. Where? Why? How? It wasn’t part of the river, it was just there. What an incredible sight. I imagined spending two more hours in this tight passage with its tight air. Would I make it? That was a question for another day.

We turned around and started crawling out. The claustrophobia stayed with me, lingering on, but at least I knew where I was headed.

Squeezing into the cold air felt like being born, or more accurately, considering all the mud, defecated.

We were coated from head to toe. The ones who hadn’t gone in the hole stood around rubbing their hands together for warmth. Two hopped up and down, shaking off drops of water. They’d been waiting all the while we crept deeper underground and were still soaking wet. Using the rope, we climbed down the cliff and rinsed off in some rapids.

We spent the next hours scrambling over tall rocks on the riverbank, trekking over gravel mini-beaches, and wading across the underground river when necessary. Now it was often deep enough that we finally went in up to our lifejackets, but we could usually still touch bottom. The cavern turned and twisted with the river, sometimes opening into high chambers, but never anything close to as large as the one where we’d stopped.

All of a sudden, an eerie glow appeared downstream. It grew larger as we approached. We took a turn and there it was, a massive hole in the earth far above the biggest chamber yet.

This was the second entrance to La Chonta, an opening called the Hoyanco del Chanchuyo (Chanchuyo’s pothole), aka la Ventana (window) or Claraboya (skylight). At roughly the halfway point of the underground river, this is a common entrance for explorers with less time or ambition than us.

It’s also a popular rock climbing spot because of the many routes on the high side of the hole. From the river it looked like the passageway from the underworld back to the living world.

Thick beams of sunlight shone into the open cavern. Here the underground river ran around big boulders and though sections of fast rapids. We sat on a section of rocks not coated with swallow droppings, ate our remaining food, and rested for about 30 minutes, while watching two people carefully scramble down the slopes from above.

Once we started hiking again, full from the food but cold from the inactivity, it didn’t take long for all the light from the hole to vanish, after only a few twists and turns. The cave was narrower here, about as big around as a subway tunnel. The smaller space meant fewer gravelly banks, bigger boulders, and deeper water. So during these final three or four hours we spent much more time in the water. It was usually deep enough that we had to swim.

To protect our knees from submerged boulders, we held our feet in front of us as we floated downstream, paddling with our hands. It was cold but a nice change from constantly slipping and scrambling in boots heavy with sand and water. Near the end I was so exhausted that the freezing water felt like a wonderful feather bed all around me. The cold became a comfort.

In some sections, there was no riverbank at all, just sheer walls on both sides. I often held Pedro’s hand through these. He couldn’t swim, although he floated in a lifejacket well enough. But when the current picked up, or when we started bumping into underwater rocks, the motion would flip him over, submerging his head. He’d struggle to float on his back again, splashing in the black water.

Each time I could see the fatigue in his eyes, along with something else—not fear, more like dread. But then, each time, his eyes would meet mine, his face would break into a smile, and he’d lift his hand and give me a thumbs-up.

Another light appeared before us. The exit, finally. Bats and swallows swarmed overhead. Warm fresh air flowed into the hole. Peering over the boulders, I saw the green of trees and shrubs. Green meant life, and life meant escape.

We pulled ourselves out of the water, panting and dripping in the half-light. Carlos scrambled over piles of stone on both sides, looking for a route out, and announced that we’d have to float out. The routes he remembered were gone.

So we floated down the rapids, first under the high cavern roof and then under the big blue sky, with tall overgrown valley walls on both sides. The water was a muddy brown, and it seemed even colder in the open air. We reached a sandy bank and looked to our left at another hole, equally large—the exit for the San Jeronimo River. We’d made it.

The sun began to set by the time we’d knocked the sand from our boots and poured the water out of our backpacks. The concrete path from the river up to the national park entrance was steep and long, but easy compared to everything else we’d hiked that day. The ground was solid, at least, and dry. By now, the sole of one of my boots had come loose. It flopped loudly with a slurping sound of water as I hiked uphill.

It was dark when we made it to the empty parking lot, where we changed clothes in a bathroom. We began the long drive back home, with a stop for tacos of course.

Hiking a subterranean river wasn’t what I expected. Besides excitement and adventure, there was awe, fear, and exhilaration unlike anything I’d ever experienced. In the tightest tunnel, it was a rush of claustrophobia, and in the biggest chamber, it was a reminder of the ant-like insignificance of the individual human.

It was also a lot of fun. And a big part of that fun—a big part of that awe—was the glimpse into the deep, dark, mysterious world below us. Once you get that glimpse, it’s unforgettable.

IF YOU WANT TO GO

Unless you’re fortunate enough to be invited by friendly and experienced locals, like I was, you’ll need to find a guide. Don’t attempt the trip by yourself. You’ll get lost, if not in the underground river then on the hike to get there.

The trail to the entrance of the underground river has many others branching off from it, and of course the underground river itself moves through total darkness with countless possible routes and dead ends.

If you find a guide and are going into the underground river, wear hiking boots. You may end up ruining your boots like I did, but that’s better than ruining your feet.

Whatever you bring, pack it in several waterproof cases. If you bring a camera, carry it in a hard case, or risk it being bashed on the rocks, like your knees and elbows.

The time to hike through the underground river is the dry season in spring, particularly March and April.

The nearest town is Taxco, which is one of the most beautiful small towns in Mexico. Its colonial-era buildings, all painted white, are scattered over mountain slopes and connected by twisting cobblestone streets and narrow alleys.

Taxco isn’t far from Mexico City and it’s a good place to inquire about the Chonta hike. If nothing else, from Taxco you can easily visit the Grutas de Cacahuamilpa National Park and its enormous, impressive chambers. Be sure to hike down the valley to check out Dos Bocas, where the two rivers flow out of the mountain.

Recommended Mexico Cave Tours

There are many caves in Mexico you can explore. Please note that these Mexico cave tours don’t go through the underground river that I described in the story above, but a few of them go to the Grutas de Cacahuamilpa National Park, which has some of the best caves in Mexico.

You can take a Cacahuamilpa cave tour from Mexico City, Taxco, or Acapulco.

The easiest and most affordable way to get to Cacahuamilpa is from Taxco. Click here for more information about this Mexico cave tour.

You can also do a Cacahuamilpa cave tour from Mexico City. On this 11-hour trip, you’ll explore Taxco after spending some time in the Cacahuamilpa caves.

A third option to visit Cacahuamilpa is from Acapulco. This 7-hour Mexico cave tour also takes you to some interesting attractions in Taxco.

Perhaps the most famous caves in Mexico are the Tolantongo Caves. Tolantongo aren’t only caves, but also hot springs. Click here for information about a Mexico cave tour to the Tolantongo Caves.

Chiapas also has some of the best caves in Mexico. If you’re in San Cristobal de las Casas, check out this Mexico cave tour to three places: Arcotete, Mamut & Rancho Nuevo.

Finally, some of the best Mexico caves are the cenotes of the Mayan Riviera. Scuba diving in cenotes is absolutely one of coolest things I’ve done in Mexico, right up there with the underground river hike I described in the story above. Click here for a good cenote tour that also stops at the Mayan ruins of Tulum.

This page contains affiliate links, which means I earn a small commission if you purchase something after clicking a link on this site. I receive this commission at no additional cost to you.

Hiking Mexico City’s Iztaccíhuatl Volcano

Unless you’re looking out an airplane window, you might not notice that Mexico City is surrounded by mountains, including the second and third highest in the country. But when you escape the dense neighborhoods of this mega-metropolis, you can see the steep slopes and sometimes snow-capped peaks off in the distance.

At least ten national parks lie within driving distance of the city, meaning ziplines, ATM rentals, horses, old ruined convents, waterfalls, caves, and hiking trails crossing expanses of pine forest. You might even see animals like white-tailed deer, weasels, the tiny teporingo rabbit, long-tailed wood partridges, horned lizards, tarantulas, and rattlesnakes.

The two biggest mountains near Mexico City are actually volcanos, one active and the other long dormant. Active Popocatépetl has a classic cone with a wisp of smoke coming from the crater, while Iztaccíhuatl has a rocky, jagged peak that gives few clues to its volcanic origins.

These two pre-Hispanic names are quite a mouthful, so they’re usually abbreviated as Popo and Izta (pronounced EES-ta). Popo is off-limits to hiking because of regular activity; significant eruptions happened most recently in 2000 and 2005, and it ejects long columns of smoke nearly every day. So the spot for hiking is on Izta, an arduous, high-altitude hike that’s only for the experienced.

Looking to hike Izta volcano on a tour from Mexico City? Check out this Iztaccihuatl volcano hiking small group tour.

To hike in Izta-Popo National Park on a full-day, private tour from Puebla, check out this full-day hike in Izta-Popo National Park.

The volcanos were revered as gods by the native Mexica, along with neighboring peak Tlaloc, named after the rain god once believed to reside in the mountain. The ruins of an ancient shrine are on the summit of Mount Tlaloc, where sacrifices of children occurred for the sake of summoning the indispensable water from the sky.

In the Nahuatl language, Popocatépetl means “mountain that steams,” as it’s been active for as long as it’s had the name. Iztaccíhuatl means “white woman” because, like many mountains in the world, people have identified the features of a reclining body in its crags and cliffs. Its many peaks are named after the white woman’s body parts, including her feet, knees, belly button, chest, and head.

Created in 1935, Iztaccíhuatl-Popocatépetl Zoquiapan National Park comprises the two volcanos and the broad saddle between them, which runs along the border of the State of Mexico, which surrounds Mexico City on three sides, and the state of Puebla to the east.

This was our destination for a Saturday of hiking. My wife and I left at five-thirty in the cold morning to begin the drive from Toluca, a mid-sized city on the opposite side of Mexico City from the national park.

Mexico City normally has some of the worst traffic in the world, but driving in the sparse early-morning weekend traffic was easy. The sun rose, beaming orange and yellow through car-exhaust haze, as we changed from multilane highways to inner-city avenues and back again, following directions to the village of Amecameca at the foot of the mountain slopes.

Leaving the highway, we drove past tamal sellers on their yellow tricycle carts, pickup trucks overflowing with pineapples and prickly pears for sale, and stray dogs sleeping in the street, who woke and scurried away always at the last second. Convoluted onramps and unmarked intersections led to a narrow two-lane road on a steady incline lined with squat concrete buildings in various degrees of disrepair. The town’s density subsided, the uphill became steeper, and suddenly we were flanked by open fields of mud and grass, with towering thick-trunked fir and cedar trees all around.

This was the road to the national park, its black asphalt alternately gleaming from morning dew or covered in fallen pine needles. Hand-painted signs hung from trees, advertising private nature parks for ziplines and horseback riding, rustic taco restaurants, and stands for pulque, a pungent white alcoholic drink homebrewed from the heart of the enormous maguey, the largest agave in Mexico. Many magueys grew on the high banks of the road, their broad leaves ending in sharp points, with every tenth or so plant sprouting an asparagus-like seed pod twice as tall as a human on tiptoes.

Sharp turns and big potholes made for slow driving, but thanks to nearly no traffic, we pulled into the parking lot at the entrance to Izta-Popo National Park at exactly eight o’clock.

We parked in front of the national park office, a steep-roofed stone and concrete building with weather-beaten steps leading to the entrance. Towering behind was the black, angry cone of Popo. A thin cord of smoke rose from its wide crater.

A tall rectangular monument stood between the road and the office. It held a large bronze plaque showing Spanish conquistadors in their armor and pointy curving helmets. The one in the middle sat upon a horse—Hernan Cortes, the notorious conqueror of Mexico.

The white sign before the plaque read “Paso de Cortes”—Cortes’s Pass, named for his journey over it in 1519 after leaving Cholula, the important pre-Hispanic city on the other side of the mountains from Mexico City, where he and his men had slaughtered between 5,000 and 6,000 people. Aided and encouraged by their new allies the Tlaxcalans, and wanting to set an example for other native groups, Cortes and his relatively small band of Spaniards gathered the city’s wealthy residents in a field before the central pyramid, and with crossbows and swords murdered as many as they could. Then they turned to the mountains, to make the final push toward the irresistible riches of Tenochtitlan, the island city of temples and markets that’s now the central part of Mexico City.

Legend has it that some of his men climbed Popo to collect sulfur for gunpowder for their canons and muskets. Then they descended into the Valley of Mexico, and the rest is history—the defeat of the Aztecs and the earliest beginnings of New Spain, later reduced to Mexico.

I imagined that little had changed in the 500 years following that fateful journey, at least not on the pass itself. The country, however, had changed practically beyond recognition, and in large measure because of Cortes’s crossing from one world into another, first from the Old World to the New, and later on the march toward death and destruction in Tenochtitlan, after leaving death and destruction behind in Cholula.

Today, pre-Hispanic Mexico may manifest as an excavated pyramid, a village with a Nahuatl name, a meal of tortillas and crickets, or even as the white alcoholic beverage pulque. But beneath these superficialities, ancient customs and beliefs persist, if remarkably transformed. Catholic saints replaced gods of nature, the Virgin of Guadalupe replaced the goddess Tonantzin, and Spanish replaced Nahuatl and hundreds of other native languages.

Now, I walked in Gore-Tex hiking boots where conquistadors once walked in boots of steel, and before them, centuries of indigenous wanderers in their huaraches, broad sandals originally woven from agave fibers, now made from leather or plastic.

Only five other vehicles were there, all pickup trucks, and one with a group of hikers standing nearby who appeared to be leaving. It was a relief—we chose to leave early not only to beat traffic and maximize our time hiking, but also to avoid crowds. The volcano nearest to Toluca, where we often hiked, typically had a long line of cars crawling toward its high-altitude parking areas, especially on weekends and after fresh snow draped its broad crater in white. I’d assumed today would be worse—it was much closer to Mexico City and its millions of potential hikers.

“No, it’s not so bad as there,” said the guard inside the park building. He was a stout man with jet-black hair and a bushy mustache, wearing a faded olive-green uniform with fraying hems and missing patches.

“Why?” I asked.

“Izta’s too difficult. It’s too high, and steep. People know it’s not easy.”

“Yes,” I said. “I read online that you need a guide.”

“One of us can take you up if you want. Or we can find someone.”

“But it’s not necessary?”

His response was a shrug.

I said, “In the Nevado de Toluca, you can drive right up to the edge of the crater, and then walk over the top and to the lakes inside the crater. There’re always many people.”

“Have you been there?”

“Yes, many times. I live in Toluca, you know.”

If you want to reach the summit of the Nevado de Toluca volcano with experienced professionals, check out this guided hike.

“Oh, I see.” He’d evidently taken me for a tourist, surely because of my appalling Spanish pronunciation. “So you go there often?”

“Very often. This is our first time here, though.”

He glanced at my hiking boots. “You want to climb Izta then?”

“Maybe not all the way to the top, but yes, we’d like to hike the trail.”

“You chose a good day. It hasn’t rained for weeks. There’s no snow up there, only the glacier.”

“You climb it?”

“Not as often as Popo.”

“Really?”

“But you can’t go up Popo. It’s closed, and dangerous.”

“Why?”

“Poison gases, the chance of an eruption. You won’t have to worry about that on Izta. Just follow the trail, up up up.”

“Sounds great. How do we get there?”

“Drive past the gate and then keep driving straight to La Joya. That’s the parking lot at the bottom of the mountain.”

“Ok.”

“Register on this form first. The fee is 57 pesos.”

“There are two of us,” I said. I filled out the form, just simple information about who I was, where I was from, and where I’d be hiking today, and paid the fee for two people.

“Enjoy it,” he said. “And come back here before you leave, so we know you’re still alive.”

I laughed. “I will.”

By now my wife had strapped on her boots and was hopping up and down in the clear thin air, rubbing her hands together. We got back in the car and drove across the mountain saddle, through a vast rolling expanse of tall yellow grass broken up by bunchy Hartweg’s pine and the Christmas-tree shape of Oyamel fir trees. The two peaks occasionally came into view high on either side, Popo behind and Izta in front, one a smooth cone and one a broad rocky crown.

A steep descent down a bumpy section of the dirt road took us to the La Joya parking lot, which had more than 10 cars already parked there. A cluster of tents was set up behind a row of crumbling cinderblock structures, where people sat at long tables eating breakfast. Ladies in winter coats and hats stood by charcoal fires cooking quesadillas and gorditas (an oval mass of corn meal with beans, meat, or vegetables inside) on flat grills called comals, and served coffee or atole (a hot rice drink) in Styrofoam cups.

We paused at the trailhead at the end of the parking lot to check a large map. A little beyond the parking lot was a small clearing on the side of a slope with benches and picnic tables. There was no wind to rustle the grass or tree branches, and above was a deep blue sky with only a few wisps of cloud.

From here the trail was quite steep and continued on the slope below a ridge. Boulders the size of coffee tables filled the trail, with thick, waist-high bushes and underbrush of a deep green all around. When in the shade, the trail was full of black puddles of frozen mud. A closer look revealed countless tiny beetles crawling in the black dirt between the puddles, each no larger than the head of a pin, and of a red so striking that they seemed to glow with a light of their own.

Small mice darted under the rocks, upon which finger-length grey lizards lay in the sun. A few times we spotted larger, fuzzier forms than mice, which we hoped was the small, short-eared teporingo rabbit, elusive and rumored to have gone extinct, or at least vanished from all but the highest volcanic regions of central Mexico, far away from the threat of poachers and packs of stray dogs.

From here we could see the Nevado de Toluca volcano to the west, the one I’d discussed with the guard earlier, across Mexico City and the less dramatic mountain range on the other side of the Valley of Mexico. Its broad crater was unmistakable, shining white in the sunlight.

The trail and the ridge met at a point below a much larger slope of scree at the base of the bulk of the mountain. We sat for a break, watching lizards hunt flies in patches of tall grass poking from between smooth weather-rounded stones.

The huge cone of Popo had disappeared behind the ridge during this first leg of the hike. Now that we were atop the ridge, it was back in view. The sun’s glare made it black as Mordor, but a more careful look showed alternating lines of green and grey-black ridges spreading downward from the crater.

Suddenly there was an eruption, silent but with a massive expulsion of grey smoke. It expanded away from the crater, its rolling motion resembling waves on a beach. It didn’t take long for this smoke to become a long horizontal line in the sky far above the regular clouds.

Several more eruptions occurred as we continued hiking, above the treeline now. Besides occasional tufts of grass, the only vegetation was a dry, colorless flower scattered among the grass and scree, the Rosa de Nieve—Snow Rose—which only grows on the slopes of the volcanos surrounding Mexico City.

The trail was pure rocks and gravel and went straight up, no switchbacks, at a more than 45-degree angle. There were many more hikers now, sometimes families wearing street clothes, and sometimes small groups wearing unnecessary gear like helmets and full rainsuits. I could only imagine how hot they must have been. Now that late morning was coming on, the air was still chilly, but the uphill hiking had made me strip down to my quick-dry t-shirt, although I still wore wool gloves and a winter hat.

We paused to drink some water. A man wearing rain gear with the hood up, a headlamp with the light turned on, a helmet, and chaps over his boots stopped to tell us, “You shouldn’t drink water.”

“What?” I asked, noticing the large ice axe hanging from his enormous backpack. After weeks of sunny weather there was no ice to climb, of course, only a relatively flat glacier far above.

“It’s bad because of the elevation. You should be drinking suero,” he replied, referring to a saline solution found in pharmacies that Mexicans drink when they are sick or hung over. Then he turned and resumed hiking.

Ok, I thought, a drink like that, or even Gatorade, would surely absorb more quickly, but water is bad? It was frustrating to hear, especially in a country with one of the highest rates of diabetes in the world. I’ve met countless Mexicans, in fact, who say they never drink water at all. Mexicans call it “natural water,” to distinguish it from the sugar water flavored with ground-up fruit, also called “water,” that people drink every day with lunch.

We quickly passed the man as he slowly panted up the trail, looking miserable under his hot, heavy gear. From there, the trail followed several sharp ridges on a steady rise into the high alpine area. The next saddle was at the ankles of the white woman, with the sheer cliffs of her feet behind.

Now that we’d reached the white woman’s body, we had views to the east. Beyond a broad flat expanse containing the cities of Cholula and Puebla were clear views of Mexico’s two other famous volcanos. The first was La Malinche, named after Cortes’s native interpreter and mistress. Today, she is also a symbol of betrayal, and indeed the word malinchista is used to describe people more interested in the ideas and fashions of the outside world, especially the U.S. or Europe, than those of Mexico. The volcano itself is another long but non-technical hike, which my wife I had done a month earlier.

Iztaccihuatl isn’t the only volcano worth hiking near Puebla and Mexico City. Check out this tour for hiking the huge volcano La Malinche.

The second volcano, its massive cone a distant triangle on the horizon, was the largest mountain in Mexico and the third highest in North America: the Pico de Orizaba, also known by its Nahautl name Citlaltépetl, which means “Star Mountain”. From this angle, La Malinche and Citlaltépetl appeared as if in a row, and in fact from the nearby peak Mount Tlaloc, every year in early February the two volcanos form a perfect line with the rising sun.

After this was a final section of sandy trail, followed by a rocky section going nearly straight up, which required scrambling over cliffs and boulders. It wasn’t too exposed, however, and there were plenty of hand and footholds.

The trail, marked by cairns and spray-painted circles on the rock, led to a broad rounded peak. From the top, the highest parts of Izta were finally in view, the imposing peaks towering high above. It was clear that the hours of hard scrambling we’d just accomplished were nothing compared to what was ahead. But first, there was a steep descent to a narrow ridge, where an aluminum shelter like a tall greenhouse sat encircled by tents. This was Shelter 19 (Refugio 19), also known as the Shelter of the Group of 100, the last chance for survival for anyone caught on the mountain during one of its frequent violent storms.

About 20 hikers stood around, drinking coffee or even beer. They’d started the previous day, or perhaps the night before. Many people join organized groups for the hike up Izta, which often leave late at night in order to arrive at the top in the morning or early afternoon. Like other hikers we’d passed, many wore helmets, but they didn’t carry ropes. I suspected that the helmets were more about making the clients feel like they were doing something important than about fulfilling a necessary safety requirement.

It was a jagged, uneven landscape all around the shelter. Every remotely flat space was occupied by a tent. Beyond was a nearly vertical climb of loose gravel, by far the most difficult part of the day. We ascended by shoving our boots and fingers into the earth and pulling ourselves upward, quite difficult now that we were above 4,700 meters (15,420 feet). The air was thin and we breathed in short, strenuous bursts.

By now the trail was nearly empty of hikers. One man passed us quickly, dressed in shorts and tennis shoes like he was out for run, with no backpack. When we eventually got above the gravel and reentered broken cliffs and tall boulders, we saw him standing by a tall metal cross, a memorial to 11 students from Guadalajara who’d died near here in 1968 after getting caught in a bad storm.

He asked how far we were planning to go. “All the way to the top?” he asked.

“I don’t think so,” I answered.

“Good idea. It’s already afternoon, and the top’s still far away.”

“And you?”

“I’ll go as far as I can. But look at the sky. It’ll probably rain soon.”

He was right. Heavy clouds were moving in rapidly, nearly covering Popo off in the distance. The long line of smoke from the morning’s eruptions had fully mixed in with the clouds, now little more than a black blur among all the white.

“Also,” he continued, “notice that no one has come down for a while. It’s just us up here.”

“Well,” I said, “We’ll get to the top of this part, and from there decide.”

“Yeah! That’s the attitude! You can do it!” With this he started climbing rapidly, hoisting himself over boulders and sprinting through the gaps between them.

His bursts of sprinting couldn’t have lasted long, though, because for the next hour it was a pure scramble up the slope of broken cliffs. Now we were much more exposed, and I avoided looking behind and down into profound chasm below us. It made me dizzy, and I felt that if I leaned too far back, I would tumble into oblivion.

The cliffs became a narrow rocky trail up a slope, and soon we came to a peak. This was the first knee, which at 5,034 meters (16,515 feet) above sea level is the least high of the six major peaks that form the crown of Izta. There was a destroyed mass of metal there, which we later learned was the ruins of the Luis Mendez Hut, a former shelter that had been devastated in a particularly powerful storm.

The view was spectacular. Below us, visible during the brief moments the clouds separated, were the twisting ridges and crags we’d hiked over, with the green expanse of the mountain saddle below and the enormous mass of Popo beyond. On the opposite side was a crater, where streaks of light brown, yellow, and pink led to a small circle at the bottom. The next mountain peaks were in sight farther above, tall and rocky, reached by long narrow ridges. I could see my breath, and when I removed my gloves my fingertips were already white.

The highest peak, found at the end of the trail, is the chest (or breast) at an elevation of 5,230 meters (17,160 feet). The next two closest to us, the second knee and then Mount Venus, appeared to be at least half an hour away. Beyond Mount Venus was a glacier, and then there were several other peaks to cross before the trail reached the chest. We realized that reaching it today was out of the question, as it would probably be dark by the time we could finish the hike down to La Joya.

The trail runner was nowhere in sight, but we did see a group of hikers slowly returning along the ridge from Mount Venus. We watched them as we ate our sandwiches, and decided that we probably had enough time to go there and back, to take a look at the glacier.

The trail leaving the first knee to reach the ridge followed an extremely steep section covered in shadow. Snow lined the trail, which was otherwise coated in slippery mud. About halfway down, as we gingerly lowered ourselves through this mud, I caught a glimpse of the impossibly steep, rocky funnel below. One wrong move, one slip, and we would slide down that funnel like Boba Fett in Return of the Jedi.

This meant that, combined with the exhaustion of a whole day hiking and the light-headedness brought on by the high altitude, we were both badly shaken when we made it to the relative safety of the ridge. Standing there watching the group move so slowly ahead, we decided that we’d gone far enough. After catching our breath and allowing our hearts to stop racing, we turned around and, after quickly re-summiting the first knee, began a long descent.