January 20, 2019

Jason Patton

Jason R. Patton, Ph.D.; Jean Baptiste Ammirati, Ph.D., University of Chile National Seismological Center; Ross Stein, Ph.D.; Volkan Sevilgen, M.Sc.

“It is clear to many of us that the Coquimbo region has an unusual, increasing seismicity that may be preparing the area for a very large earthquake near the end of the present century.”

Raul Madariaga, Ecole Normale Superieure (Paris) and Universidad de Chile (Santiago)

An earthquake located just beneath the subduction zone of the Peru-Chile Trench strongly shook Coquimbo and La Serena, and was felt up to 400 km away in Santiago. This quake struck just north of the edge of the M=8.3 Illapel megathrust earthquake, which launched a destructive tsunami in 2015.

Deep earthquake was felt broadly

On 20 January 2019 there was an M=6.7 earthquake along the convergent plate boundary on the west coast of Chile, about the same size as the 1994 Northridge quake in southern California or about the size of an earthquake that might hit the San Francisco Bay area In northern CA. The earthquake was quite deep (53 km, or about 33 miles), so was not as damaging as those CA examples. However, it was broadly felt with over 800 USGS Did You Feel It reports at the time we write this article.

Reports from the USGS Did You Feel It website survey

For most earthquakes that have a potential to damage people, buildings, or infrastructure, the U.S. Geological Survey prepares an estimate of these types of damage. The PAGER alert is based on the strength of measured and modeled shaking (explained in greater detail here). For this M=6.7 earthquake PAGER assigns a 43% chance that there will be between 10 and 100 fatalities, and a 53% chance that there will be economic losses between $10 and $100 million (USD).

The largest city near the earthquake, Coquimbo, was hit by a tsunami in 2015 when the adjacent section of the subduction zone ruptured. Below is a photo taken following the 2015 M=8.3 earthquake and tsunami. There are over 300,000 people in Coquimbo and the nearby city of La Serena that likely experienced strong to severe shaking intensity from the M=6.7 event. We were quite surprised that the M=6.7 actually caused as much damage as it has, especially in comparison with the 2015 M=8.3 earthquake, which shook less despite being about 300 times larger.

The Chilean Navy (SHOA) alert system worked very well yesterday. The SHOA tsunami alert that was withdrawn about 30 min after the earthquake, once it was clear that this was not a subduction event. During that half hour, several thousand people followed instructions and took evacuation routes until told to return. This is a valuable test-run of tsunami warnings, and a credit to Chile.

Plate motions: locked or slipping?

The deep marine trench offshore the west coast of Chile is formed by a subduction zone where the Nazca plate is shoved beneath the South America plate. This megathrust fault has a variety of material properties and structures that appear to control where the plates are locked, and so accumulating stress towards the next large earthquake, and where they are slipping ‘aseismically’ past each other, and so with a low likelihood of hosting a great quake.

Below is a map that shows the location of plate boundaries in the region. The majority of high hazard is associated with the subduction zone fault.

Seismic hazard for South America (Rhea et al., 2010). The numbers (“80”) indicate the rate at which the Nazca Plate is subducting beneath South America. 80 mm/yr = 3 in/yr.

Are you in earthquake country? Do you know what the earthquake hazards are where you live, work, or play? Temblor uses a model like the USGS model to forecast the chance that an area may have an earthquake. Learn more about your temblor earthquake score here.

These locked zones are generally where megathrust earthquakes nucleate. In Chile, below a depth of about 50 km (~30 miles) the plate interface is not locked (Gardi et al., 2017), so megathrust fault earthquakes are generally shallower than this depth. Earthquakes deeper than this generally occur within the Nazca plate slab, called ‘slab’ earthquakes because they lie are within the subducting slab. Often these slab earthquakes are extensional, as was the 20 January 2019 M=6.7 quake.

Cross section of the subduction zone that forms the Chile Trench.

Below is an aftershock map prepared by Jean-Baptise Ammirati at the University of Chile and the Chilean National Seismic Network.

We have added the arrows to suggest that the aftershock alignment hints at a west-dipping tensional fault.

Earthquake history along the Peru-Chile trench

Much of the megathrust has slipped during earthquakes in the 20th and 21st centuries. The historic record of earthquakes is shown in the figure below. The vertical lines represent the size and extent of the earthquake. The largest earthquake ever recorded by seismometers was the 1960 M=9.5 Chile shock that caused widespread damage, triggered landslides, and generated a trans-oceanic tsunami that destroyed the built environment and caused casualties in Hawaii, Japan, and the west coast of the USA (e.g. Crescent City).

In 1922 there was an M=8.5 earthquake in the region of today’s M=6.7 quake (Ruiz and Madariaga, 2018). According to Dr. Raul Madariaga, this 1922 event was a subduction zone earthquake that generated a trans-oceanic tsunami which caused damage in Japan and launched a 9m (30 feet) wave just north or Coquimbo, Chile. There has not been a large earthquake in the area of the 1922 earthquake in almost a century, a time longer than average when compared to the rest of the subduction zone. Nevertheless, there was a 129-year pause between the 1877 and 2005 events to the north.

Also remarkable is the apparent northward progression of great quakes with time from the 1922 event, to 1946, 1966, 1995, 2007, and 2014, for a distance of 1200 km (11° of latitude).

Historic earthquake record (on the left) coincides with the map of the megathrust showing an estimate of where the fault is stuck and where it may be freely slipping. The M=6.7 earthquake epicenter is located near the blue star. Slab earthquakes are labeled with a gray star (e.g. 1997 discussed below).

The nearby 1997 sequence started from the north and advanced to the south during the

month of July 1997, until it produced the 15 October Punitaqui 1997 earthquake. Seismologists will monitor this event to see if there is any seismic migration, which is rare.

Geologists use GPS data, remote sensing data, and physical measurements of the Earth to monitor how the Earth deforms during the earthquake cycle. The observations can be “inverted” to estimate where the fault is locked and where it is slipping. The figure above shows an interpretation of where the subduction zone fault is locked, and where it may be slipping. Note how the M=6.7 earthquake struck in an area where the megathrust may be freely slipping.

What does it mean?

The historic record of earthquakes along the subduction zone makes clear that the absence of megathrust earthquakes for almost a century at the location of the M=6.7 event is unusually long. While it is possible that the Coquimbo portion of the megathrust is not fully locked, it would be prudent for those living along the coast of Chile would to practice their earthquake drills and prepare their homes and finances to withstand effects from a future large earthquake.

Stay tuned to the latest news about earthquake, tsunami, landslide, liquefaction, and other natural hazards by signing up for our free email service here.

Citation: Patton J.R., Ammirati J.B. ,Stein R.S., Sevilgen V., 2019, Strong shaking from central coastal Chile earthquake: What does it reveal about the next megathrust shock?, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.012

References

Beck, S., Barrientos, S., Kausel, E., and Reyes, M., 1998. Source Characteristics of Historic Earthquakes along the Central Chile Subduction Zone in Journal of South American Earth Sciences, v. 11, no. 2, p. 115-129, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-9811(98)00005-4

Gardi, A., A. Lemoine, R. Madariaga, and J. Campos (2006), Modeling of stress transfer in the Coquimbo region of central Chile, J. Geophys. Res., 111, B04307, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JB003440

Métois, M., Vigny, C., and Socquet, A., 2016. Interseismic Coupling, Megathrust Earthquakes and Seismic Swarms Along the Chilean Subduction Zone (38°–18°S) in Pure Applied Geophysics, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-016-1280-5

Rhea, S., Hayes, G., Villaseñor, A., Furlong, K.P., Tarr, A.C., and Benz, H.M., 2010. Seismicity of the earth 1900–2007, Nazca Plate and South America: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010–1083-E, 1 sheet, scale 1:12,000,000.

Ruiz, S. and Madariaga, R., 2018. Historical and recent large megathrust earthquakes in Chile in Tectonophysics, v. 733, p. 37-56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2018.01.015

Learn more about the plate tectonics in this region here.

See the full article here .

five-ways-keep-your-child-safe-school-shootings

Please help promote STEM in your local schools.

![]()

Stem Education Coalition

![]()

Earthquake Network project

Earthquake Network is a research project which aims at developing and maintaining a crowdsourced smartphone-based earthquake warning system at a global level. Smartphones made available by the population are used to detect the earthquake waves using the on-board accelerometers. When an earthquake is detected, an earthquake warning is issued in order to alert the population not yet reached by the damaging waves of the earthquake.

The project started on January 1, 2013 with the release of the homonymous Android application Earthquake Network. The author of the research project and developer of the smartphone application is Francesco Finazzi of the University of Bergamo, Italy.

Get the app in the Google Play store.

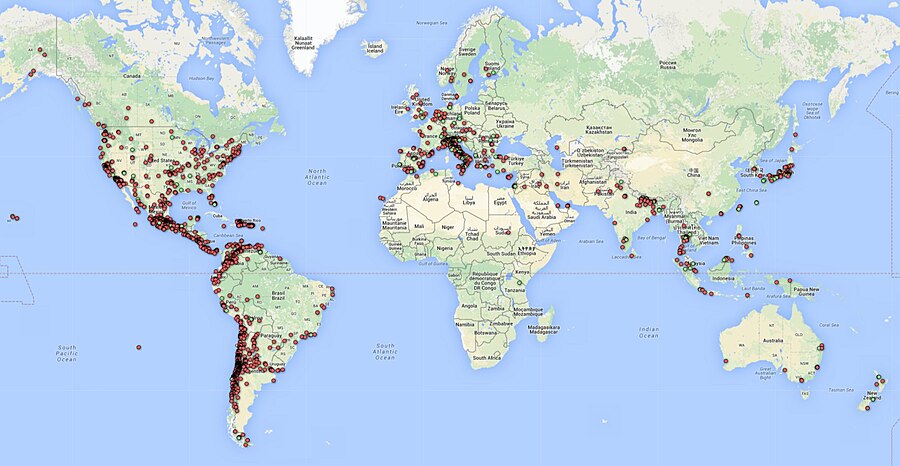

Smartphone network spatial distribution (green and red dots) on December 4, 2015

Meet The Quake-Catcher Network

The Quake-Catcher Network is a collaborative initiative for developing the world’s largest, low-cost strong-motion seismic network by utilizing sensors in and attached to internet-connected computers. With your help, the Quake-Catcher Network can provide better understanding of earthquakes, give early warning to schools, emergency response systems, and others. The Quake-Catcher Network also provides educational software designed to help teach about earthquakes and earthquake hazards.

After almost eight years at Stanford, and a year at CalTech, the QCN project is moving to the University of Southern California Dept. of Earth Sciences. QCN will be sponsored by the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) and the Southern California Earthquake Center (SCEC).

The Quake-Catcher Network is a distributed computing network that links volunteer hosted computers into a real-time motion sensing network. QCN is one of many scientific computing projects that runs on the world-renowned distributed computing platform Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC).

The volunteer computers monitor vibrational sensors called MEMS accelerometers, and digitally transmit “triggers” to QCN’s servers whenever strong new motions are observed. QCN’s servers sift through these signals, and determine which ones represent earthquakes, and which ones represent cultural noise (like doors slamming, or trucks driving by).

There are two categories of sensors used by QCN: 1) internal mobile device sensors, and 2) external USB sensors.

Mobile Devices: MEMS sensors are often included in laptops, games, cell phones, and other electronic devices for hardware protection, navigation, and game control. When these devices are still and connected to QCN, QCN software monitors the internal accelerometer for strong new shaking. Unfortunately, these devices are rarely secured to the floor, so they may bounce around when a large earthquake occurs. While this is less than ideal for characterizing the regional ground shaking, many such sensors can still provide useful information about earthquake locations and magnitudes.

USB Sensors: MEMS sensors can be mounted to the floor and connected to a desktop computer via a USB cable. These sensors have several advantages over mobile device sensors. 1) By mounting them to the floor, they measure more reliable shaking than mobile devices. 2) These sensors typically have lower noise and better resolution of 3D motion. 3) Desktops are often left on and do not move. 4) The USB sensor is physically removed from the game, phone, or laptop, so human interaction with the device doesn’t reduce the sensors’ performance. 5) USB sensors can be aligned to North, so we know what direction the horizontal “X” and “Y” axes correspond to.

If you are a science teacher at a K-12 school, please apply for a free USB sensor and accompanying QCN software. QCN has been able to purchase sensors to donate to schools in need. If you are interested in donating to the program or requesting a sensor, click here.

BOINC is a leader in the field(s) of Distributed Computing, Grid Computing and Citizen Cyberscience.BOINC is more properly the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing, developed at UC Berkeley.

Earthquake safety is a responsibility shared by billions worldwide. The Quake-Catcher Network (QCN) provides software so that individuals can join together to improve earthquake monitoring, earthquake awareness, and the science of earthquakes. The Quake-Catcher Network (QCN) links existing networked laptops and desktops in hopes to form the worlds largest strong-motion seismic network.

Below, the QCN Quake Catcher Network map

ShakeAlert: An Earthquake Early Warning System for the West Coast of the United States

The U. S. Geological Survey (USGS) along with a coalition of State and university partners is developing and testing an earthquake early warning (EEW) system called ShakeAlert for the west coast of the United States. Long term funding must be secured before the system can begin sending general public notifications, however, some limited pilot projects are active and more are being developed. The USGS has set the goal of beginning limited public notifications in 2018.

Watch a video describing how ShakeAlert works in English or Spanish.

The primary project partners include:

United States Geological Survey

California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (CalOES)

California Geological Survey

California Institute of Technology

University of California Berkeley

University of Washington

University of Oregon

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

The Earthquake Threat

Earthquakes pose a national challenge because more than 143 million Americans live in areas of significant seismic risk across 39 states. Most of our Nation’s earthquake risk is concentrated on the West Coast of the United States. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has estimated the average annualized loss from earthquakes, nationwide, to be $5.3 billion, with 77 percent of that figure ($4.1 billion) coming from California, Washington, and Oregon, and 66 percent ($3.5 billion) from California alone. In the next 30 years, California has a 99.7 percent chance of a magnitude 6.7 or larger earthquake and the Pacific Northwest has a 10 percent chance of a magnitude 8 to 9 megathrust earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone.

Part of the Solution

Today, the technology exists to detect earthquakes, so quickly, that an alert can reach some areas before strong shaking arrives. The purpose of the ShakeAlert system is to identify and characterize an earthquake a few seconds after it begins, calculate the likely intensity of ground shaking that will result, and deliver warnings to people and infrastructure in harm’s way. This can be done by detecting the first energy to radiate from an earthquake, the P-wave energy, which rarely causes damage. Using P-wave information, we first estimate the location and the magnitude of the earthquake. Then, the anticipated ground shaking across the region to be affected is estimated and a warning is provided to local populations. The method can provide warning before the S-wave arrives, bringing the strong shaking that usually causes most of the damage.

Studies of earthquake early warning methods in California have shown that the warning time would range from a few seconds to a few tens of seconds. ShakeAlert can give enough time to slow trains and taxiing planes, to prevent cars from entering bridges and tunnels, to move away from dangerous machines or chemicals in work environments and to take cover under a desk, or to automatically shut down and isolate industrial systems. Taking such actions before shaking starts can reduce damage and casualties during an earthquake. It can also prevent cascading failures in the aftermath of an event. For example, isolating utilities before shaking starts can reduce the number of fire initiations.

System Goal

The USGS will issue public warnings of potentially damaging earthquakes and provide warning parameter data to government agencies and private users on a region-by-region basis, as soon as the ShakeAlert system, its products, and its parametric data meet minimum quality and reliability standards in those geographic regions. The USGS has set the goal of beginning limited public notifications in 2018. Product availability will expand geographically via ANSS regional seismic networks, such that ShakeAlert products and warnings become available for all regions with dense seismic instrumentation.

Current Status

The West Coast ShakeAlert system is being developed by expanding and upgrading the infrastructure of regional seismic networks that are part of the Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS); the California Integrated Seismic Network (CISN) is made up of the Southern California Seismic Network, SCSN) and the Northern California Seismic System, NCSS and the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network (PNSN). This enables the USGS and ANSS to leverage their substantial investment in sensor networks, data telemetry systems, data processing centers, and software for earthquake monitoring activities residing in these network centers. The ShakeAlert system has been sending live alerts to “beta” users in California since January of 2012 and in the Pacific Northwest since February of 2015.

In February of 2016 the USGS, along with its partners, rolled-out the next-generation ShakeAlert early warning test system in California joined by Oregon and Washington in April 2017. This West Coast-wide “production prototype” has been designed for redundant, reliable operations. The system includes geographically distributed servers, and allows for automatic fail-over if connection is lost.

This next-generation system will not yet support public warnings but does allow selected early adopters to develop and deploy pilot implementations that take protective actions triggered by the ShakeAlert notifications in areas with sufficient sensor coverage.

Authorities

The USGS will develop and operate the ShakeAlert system, and issue public notifications under collaborative authorities with FEMA, as part of the National Earthquake Hazard Reduction Program, as enacted by the Earthquake Hazards Reduction Act of 1977, 42 U.S.C. §§ 7704 SEC. 2.

For More Information

Robert de Groot, ShakeAlert National Coordinator for Communication, Education, and Outreach

rdegroot@usgs.gov

626-583-7225