With the home video boom in the early 80s, anime found itself a venue with which to get a bit experimental. Quickly the format became a place for creators to build passion projects or un-TV-friendly projects in, many of these being incredibly niche titles or animation showcases. The infamous Birth OVA, for example, was horribly mismanaged and with a baffling script, but became a landmark production just for the showcase of Yoshinori Kanada and his cohorts creating a completely over-the-top animation experience. The OVA also became a place where young creators could show off in as grand a fashion as possible. The three-episode Fight! Iczer-One was the first project for a very young Masami Obari, whose extensive key animation work on the OVA led to the now-iconic “Obari punch” referenced in hundreds of later series. The higher production values due to less constrained schedules and the lower risk meant that OVAs became the premiere stage for some of the bigger shifts in the industry during the 80s.

Perhaps the undisputed king of the 80’s OVA, however, was Mamoru Oshii, soon-to-be director of Ghost In The Shell. Directing literally the first OVA ever with Dallos, before making the arthouse Angel’s Egg with character designer Yoshitaka Amano and the mech show Patlabor, Oshii’s directorial contributions in the market are memorable for a reason. However, his final OVA is talked about much less in the popular sphere than the others, despite having an enormous impact on contemporary anime as we know it.

Gosenzo-sama Banbanzai! (roughly “Long Live the Ancestors!”) is a strange tale about a young girl who, one day, appears at the door of the Yomota family, claiming to be the granddaughter of the teenage son Inumaru, and has traveled back in time to meet him. The family experience heavy tensions, as the mother is determined to reveal Maroko’s true nature with the help of a private detective, while the father and Inumaru take out a loan and move into a new home; Inumaru attempts (in vain) to woo Maroko, while a “time patroller” chases them in an attempt to stop Maroko. The script itself is, for the time, completely eccentric, taking on the form of an elaborate stage play in which the characters are actors, and many conventions of staging and framing are adapted from this. The metaphors are as blunt as humanly possible – for example, when Inumaru is forced to work to pay off a debt, he’s chained by leash and collar to the establishment he works at – and almost all the dialogue is delivered directly to the audience, either via monologue or musical sequence, complete with spotlights and set dimming.

Unfortunately, very little actual discussion exists about Gosenzo-sama in English, especially around it’s technical innovations, because of its lack of Western release and the fact that it is largely overshadowed by being a niche OVA, and so most, if not all, discussion centres around the story elements. However, in Japan, it’s considered a milestone of animation, and impactful enough on the industry that it brought about a big change in the way that animators approached realism.

Released in the same year with one of the most popular character designers of the 1980s, Haruhiko Mikimoto’s designs for Gundam 0080: War In The Pocket.

While Disney could get away with using their production time to draw a considerable amount of keyframes at a high framerate, the anime industry wasn’t so lucky, churning out anime on ridiculously tight schedules by frequently undertrained staff. In order to achieve realism many, if not all, studios relied on detailed character drawings and a limited number of keyframes, leaving in-betweens to do much of the heavy lifting for smooth motion. The complex and detailed character designs meant that animating people moving was a slow process, leaving most shots as static “lip-flapping”, and even when they did move, while it was often a smooth motion, it often lacked weight or looked stilted. It wasn’t uncommon, especially until the early 1980s, to see keyframes evenly spaced apart. The main problem with this approach was that the “important” key-frames would be easily discernable from the in-betweens. The 1988 Akira, for example, was a landmark production with a huge budget, and boasted incredibly smooth animation as a result, but the keyframes were a big factor in limiting the realism of the movie’s motion, as they often stuck out as stopping points in the arc of an object’s trajectory.

Which leads us to Gosenzo-sama Banbanzai!. There are a number of young animators on this project who would go on to become icons of the industry; Shinya Ohira and Shinji Hashimoto, both young animators who previously worked on Akira; Mitsuo Iso, another young animator who was previously one of many animation directors on Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack; alongside other names like Tatsuyuki Tanaka, Takeshi Honda, Kazuchika Kise, Osamu Tanabe, Masahito Yamashita, and Norio Matsumoto. The more veteran Satoru Utsunomiya would bring them all together in his first job as an animation director and character designer on an anime, with some assistance on animation direction by Shinji’s older brother, Koichi Hashimoto.

Satoru Utsunomiya’s character designs for Gosenzo-sama Banbanzai!

Perhaps the most immediately striking aspect of the show’s appearance, before even getting to it in motion, is how completely unorthodox the character designs actually are. In the 1980s character design was dominated almost entirely by names like Haruhiko Mikimoto and Yasuhiko Yoshikazu, who, along with many imitators, gave the industry a somewhat homogenous look that focused on detailed hair and clothing and softened facial features. By contrast, the exaggerated and highly simplified designs in Gosenzo-sama are a world apart. Characters are created, almost literally, out of basic shapes and lines – to the point that elbow and knee joints, heads and wrists have distinctive lines delineating where the joint is. The line count compared to the standard anime of the time is next to nothing, meaning for the animators that it would be considerably faster to animate as they didn’t have to worry about tons of moving parts. Also of note; the show’s opening animation, a depiction of TV static with abstract shapes appearing to house the credits, was all hand-drawn (yes, even the static), done entirely by one animator, Kooji Nanke.

Where Gosenzo-sama really stands out, however, and where Utsunomiya’s influence had the most far-reaching effect, was in the animation itself. The first major change was that there was a shift in focus from in-betweens to keyframes. Rather than drawing a few crucial keyframes and filling in the gaps, the animators on Gosenzo-sama were instead tasked with drawing considerably more keyframes, with a reduced emphasis on in-betweens. By making many more points at which the motion could be controlled, rather than just a start and end point, the motion can be manipulated into far more realistic movement. In a 2000 interview with WEB Style, Utsunomiya puts it like this: “If you animated as you would on a normal TV anime and only increased the number of in-betweens, if they were in service of unrealistic movement then it would look smooth, but not real. [Yasuo] Otsuka-san and [Hayao] Miyazaki-san drew Castle of Cagliostro on threes, right? If you have animators capable of conceptualising realistic movement, then you can achieve realism with threes.”

Paired with this new approach was a larger focus on joint dynamics and accurate physics, portraying an accurate motion instead of an accurate form. For example, the show made correct usage of cast shadows, which had previously been an afterthought in anime and only roughly approximated, and rarely appeared on the character model itself. Gosenzo-sama made extensive use of accurately portrayed shadows in order to heighten the level of realism. The show even reintroduced smears and squash-and-stretch to anime – something that had been largely put aside by the studios of the time because of the over-reliance on good-looking drawings.

Episode 4’s musical segment, animated by Satoru Utsunomiya himself.

The low-budget but incredibly high-quality and realistic animation came as a huge shock to many in the industry, leading the show’s impact to be known, appropriately, by the nickname “Gosenzo-sama shock”. Some of the aforementioned animators on the show, previously already sought-after as young talent, began taking on the lessons of Utsunomiya’s approach and adding their own spin, quickly becoming some of the most influential animators of the 1990s. Rather than a massive shift, however, it was more of a breaking of limitation – where Japanese animation was previously held back by some preconceived notions that affected the quality of animation, Utsunomiya’s approach acted as a push in the right direction, prompting artists to take what they were already good at and apply it much more to their work.

Shinya Ohira and Shinji Hashimoto, two names now ubiquitous with each other but who had already begun a partnership of sorts, were contracted by the OVA company AIC to do animation direction for the first episode of The Hakkenden in 1991. At the same time, Utsunomiya moved to working on Koji Morimoto’s movie Peek The Whale as animation director alongside another industry legend, Toshiyuki Inoue. This moment immediately proceeding the show is probably the best indication of the impact that Gosenzo-sama had on its animators. Hashimoto and Ohira’s animation direction is heavily reminiscent of Utsunomiya’s, especially noticable in close-ups during talking sequences, where characters mouths will deform much in the same way, and the general conception of movement still shows some noticeable hallmarks. A few years later, Shinya Ohira would direct Episode 10 of The Hakkenden, collaborating with Masaaki Yuasa as animation director in an early iteration on the loose, expressionist style that both they and Hashimoto would eventually become famous for, but which contained its roots in the influence that Satoru Utsunomiya had on Ohira.

Mitsuo Iso’s beach scene from Episode 4.

Perhaps the most important name attached to Gosenzo-sama, however, is Mitsuo Iso. As one of the, if not the best animator of the 1990s, Iso made a name for himself with an incredibly strong conceptualisation for realism. While he did have scenes previously that showcased his ability (like his work on the famous opening scenes of War In The Pocket in that same year), Gosenzo-sama is the first project where his distinctive style shines through, with his standout segment being a long scene in Episode 4. Compared to other animators on the project, Iso seemed to have come to a different conclusion as to how to use Utsunomiya’s ideas, and his scenes are comparatively much more lively and intense than everyone else’s, making considerably more use of a high drawing count. As his career would continue Iso would evolve this even further, creating what eventually became known as “full-limited” animation – drawing every single frame as a keyframe, but still skipping over every other frame as you would in limited. Iso’s advanced conceptualisation of motion would, ironically, greatly influence Satoru Utsunomiya in return.

By 1995 the entire industry had practically caught on to the ideas and many high-profile animators were now frequent users of the techniques. When Mamoru Oshii directed his most famous work, Ghost In The Shell, the contemporary realistic school of animation had fully emerged and were heavily represented on this project. This is also the project where Mitsuo Iso created one of his most celebrated scenes, the battle with the tank robot. From here he would only go on to animate more iconic scenes; most notably, contributing key animation to several episodes of Neon Genesis Evangelion as well as directing an episode, before animating by far his most popular sequence, a large chunk Asuka’s fight in End of Eva.

Between them Utsunomiya, Iso, Ohira and Hashimoto would become major influences on various styles and schools of animation, and all still continue to work and influence others to this day. The modern web-gen animators, the people who made their name posting their animation work on the internet, owe much to Satoru Utsunomiya and co. for allowing their current, keyframe-intensive style to emerge – in fact, it was Utsunomiya himself who helped this school of animation break into the industry, being an early major proponent of digital animation and giving several of them an early spotlight, as well as helping to discovering young talent like Ken’ichi Kutsuna.

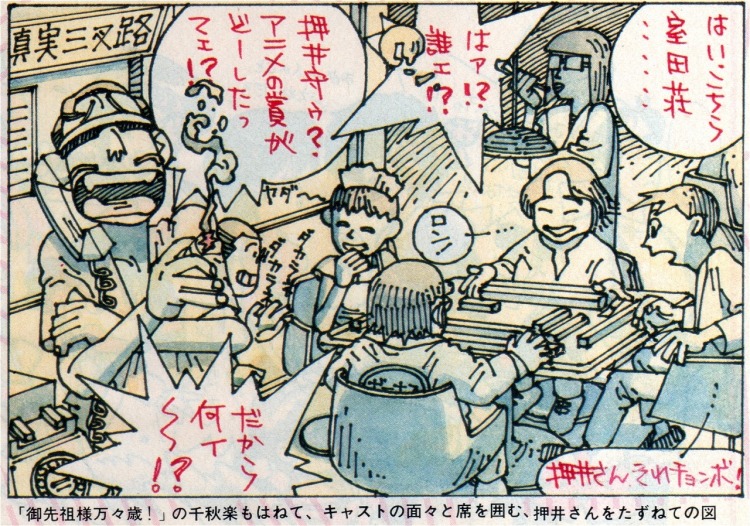

While it may not be apparent at first how influential and important Gosenzo-sama‘s influence was on anime as a whole, seeing as much of it occurred behind the scenes, it’s an important legacy to remember, especially as it occurred right as the industry first began to break out internationally. Despite being largely overshadowed by the gigantic Akira just a year before, and largely ignored in the West, the changes in the production process that the show introduced still exist as a core aspect of the anime pipeline today, and many Japanese fans still consider it an important milestone in the history of anime. Currently the show is locked away in Studio Pierrot’s vaults, with the last official release being a Japanese DVD from 2000, never officially translated into English. As the show approaches it’s 30th anniversary in 2019, maybe it’s time this piece of history had another moment in the spotlight.

Satoru Utsunomiya illustration appearing in a 1990 issue of Animage.

You must be logged in to post a comment.