Every day at 08:00, 78-year-old Darcy Dias da Cunha arrives at his local cemetery. It’s on the top of a hill, and as the sun continues to rise, he looks out over the small city of Brumadinho.

Darcy Dias da Cunha and his dog

Overhead, the deafening sound of helicopter rotor blades fills the air. Rescue workers are being ferried out to the mud that lies like a rust-red scar through the valley. They will not cease their search for bodies until dusk.

Darcy, a father of 12, has spent every day at the cemetery since the dam collapsed. Here he sits, waiting for the call that will tell him the body of his 27-year-old daughter Rosaria, a mother of two, has been found beneath the thick, toxic mud.

“I'm just waiting for her to arrive," he says. “I know the morgue will call the cemetery as soon as they identify her.”

Darcy's daughter Rosaria

A month on from the collapse, 171 people have been confirmed dead, but the recovery operation continues to search for the bodies of another 141 people - all reported missing by their families.

In this tight-knit Catholic city, where almost everyone either worked at the mine or knew someone who did, the community is still in shock.

Dozens of matching funeral wreaths are visible across the city, all paid for by the company that owns the mine

When Darcy and his wife Helena Sansao heard that their daughter was among the missing, they got in to a friend’s car and drove for two hours to the nearest large hospital in Belo Horizonte. It’s the capital city of the state of Minas Gerais, which directly translates as “general mines”.

Rosaria wasn’t there, but the couple - like many others who had rushed to the hospital - were asked to provide DNA samples.

So far, more than 530 samples have been collected from those searching for missing family members.

When the dam was breached, a tidal wave of red sludge surged through the valley with such force, that everything in its way was crushed.

The force tore bodies apart.

Due to the number of casualties, Atenaguos Moreira de Jesus only discovered his friend had died on the day of his burial

In the cemetery, gravedigger 63-year-old Atenaguos Moreira de Jesus explains that one of the hardest parts of his job is supporting families when body parts rather than whole bodies have been recovered.

“My job is to dig holes. But now the biggest hole is in my heart,” he says. “With all the love I have, this is the last thing I can do for my friends.

“I worry about the ones who won't be able to bury their relatives. I won't be able to do my job. It’s as if I have failed.”

Darcy looks on as other families come to bury their dead. Sheltering from the warm summer rains, punctuated by thunder, a snaking procession of black umbrellas follows the pace set by a pandeiro, a Brazilian drum.

But Darcy continues to wait. He says this is where he feels closest to God and most able to cope with news about his daughter, when and if it comes.

“I want to carry her coffin,” he says. “I'm still strong. I do not want to die before doing this.”

It was lunchtime on 25 January.

Every day, along with a couple of hundred other employees of Vale, the huge Brazilian company that owns the mine, Rosaria bought her lunch from the canteen. She worked in the administration office which was just five minutes by shuttle bus from both the dam and the canteen.

But by 12:28 local time, everything was destroyed.

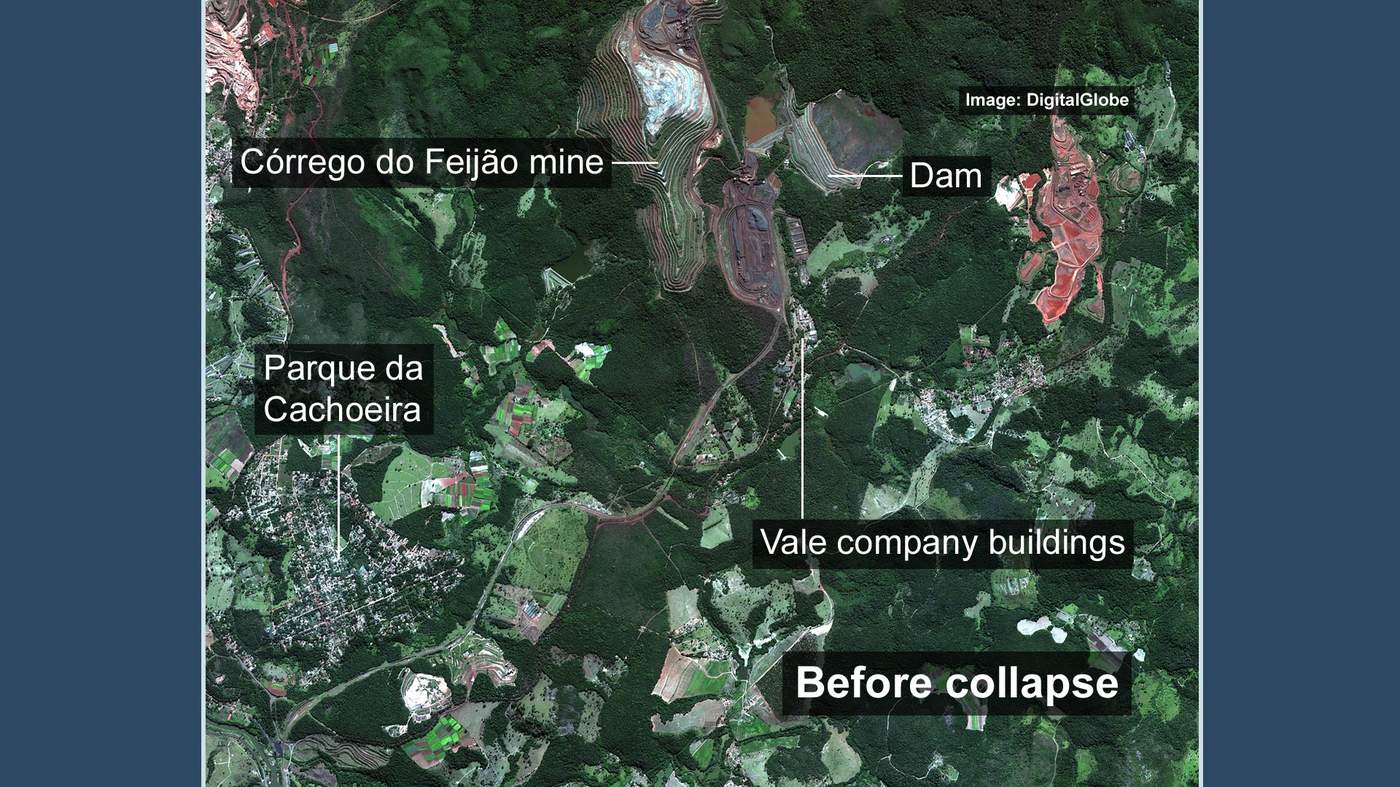

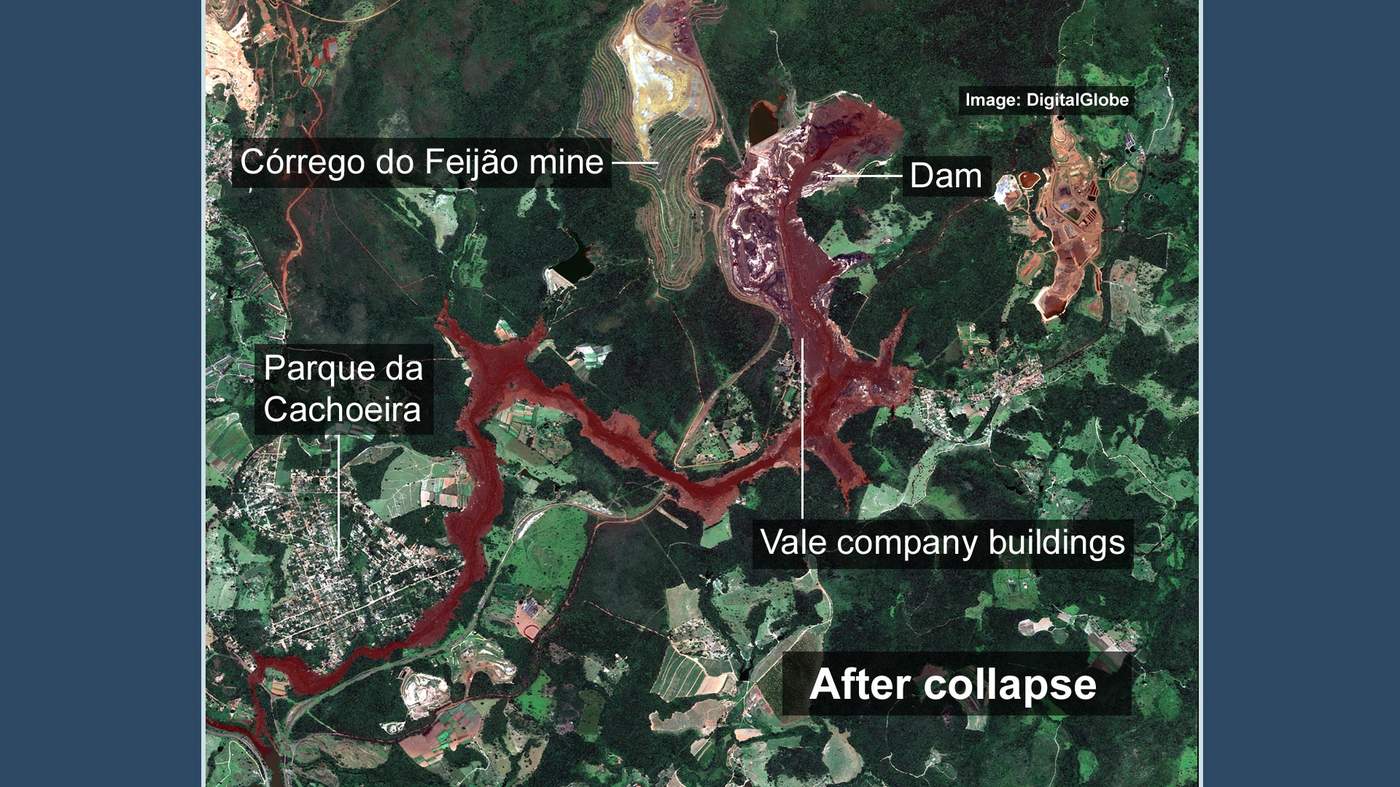

The 86m (282ft) high mining dam close to the city of Brumadinho had collapsed.

Within 90 seconds, the staff canteen and offices, as well as dozens of heavy vehicles were engulfed by mud.

Ana Paula da Silva Mota was a heavy-duty truck driver at the mine. She was proud of her job, transporting more than 90 tonnes of iron ore at a time in her 11m-long truck, from the mine to the train wagons.

She was inside her truck, just 550m from the dam when it broke.

"I was facing the dam. I think I was one of the first people to see [the torrent], I couldn’t believe it," says Ana Paula.

At first she couldn’t comprehend what was happening.

"I thought there had been an explosion at the mine," she says.

But only moments later she realised that the dam had burst.

"We thought this dam was dry,” she says. “From above, it looked like a soccer field. It was hard, solid, not made of mud. No-one could have imagined that it looked like that underneath."

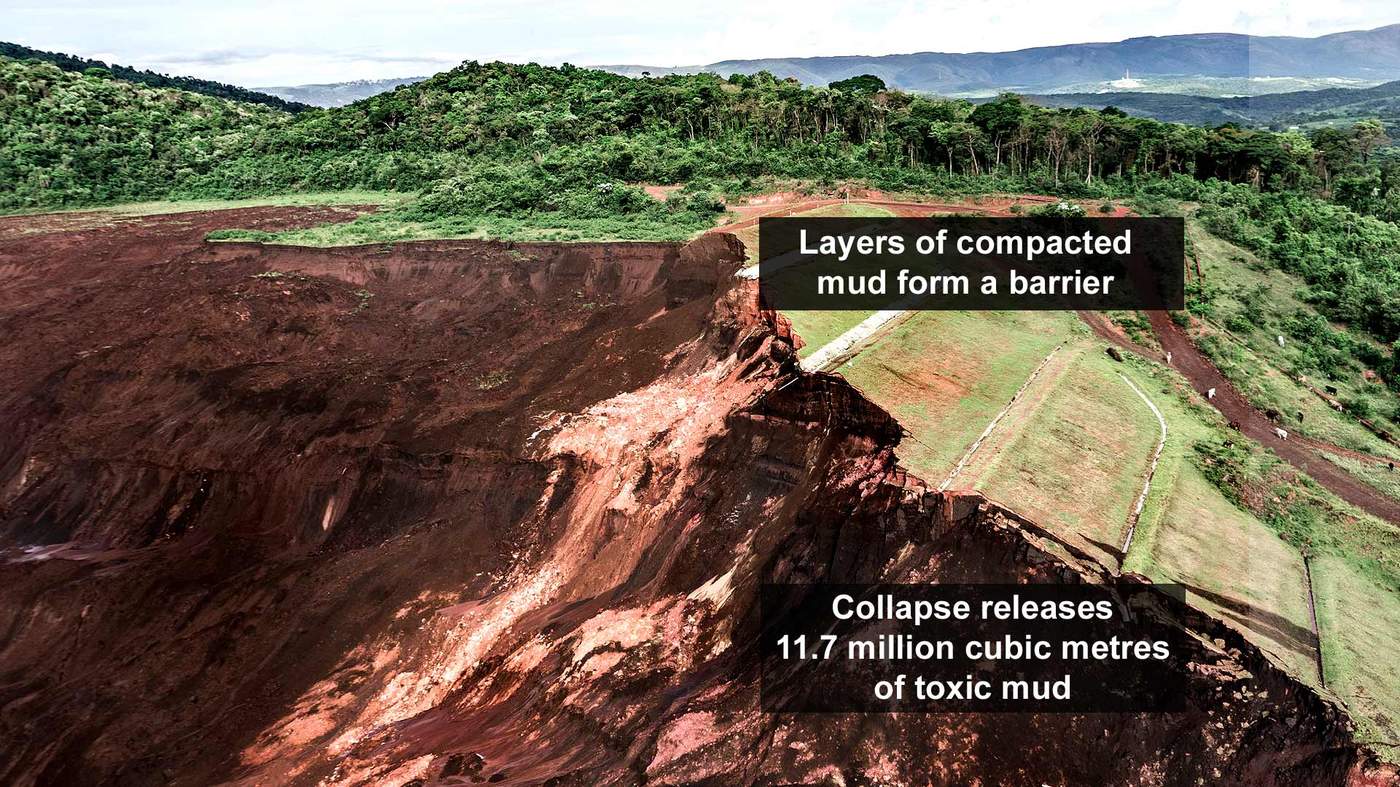

Within seconds, 11.7 million cubic metres of liquid waste cascaded down the valley at more than 70km/h (43mph). The canteen building and everyone in it was buried beneath a torrent of mud.

Ana Paula grabbed the radio.

"I got on the radio and I started screaming, 'Run, run, the dam has broken’. I later found out there were people who escaped because they had heard a woman crying and shouting on the radio. That was me," she says.

The wave of toxic mud had come within metres of Ana Paula’s truck before flowing down the valley. She says she has lost more than 20 colleagues in the tragedy, including her aunt.

Nearby homes, farms, plantations and forests were engulfed in mud. And in the nearby village of Córrego do Feijão and the neighbourhood of Parque da Cachoeira many houses were completely destroyed.

"The noise was so loud. The trees were cracking as if a fire was coming from the woods,” says local resident 65-year-old, Telmilia Duraes da Rocha.

Telmilia Duraes da Rocha and her husband

Telmilia and her husband also escaped just in time, but lost everything.

“We ran out of the car and saw the avalanche of mud coming towards us destroying everything in front of us. This house was was my life, my dream,” she says.

The dam that collapsed contained waste material - “tailings” - from the iron ore operation at the mine just behind it.

The cheapest way to store these by-products is to seal them behind a dam. Water is then drained away, so the waste sludge hardens. Grass is even grown on top - hence Ana Paula’s description of a football field.

However, if the sludge gets wet, “liquefaction” can occur.

The dam near Brumadinho posed an extra risk as its walls were also constructed of layer upon layer of “tailings”.

These types of dams, known as “upstream tailings dams”, are susceptible to cracks if they become waterlogged. These cracks can cause the structure to collapse.

This design is used by many companies all over the world, including in Canada and Australia. However, these dams need regular monitoring and up-keep.

"They are common in Brazil because they are cheap and quick to build,” says geologist Eduardo Marques, a professor at the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV). “But they are also the most dangerous. In several other countries they have been banned.”

On the day of the collapse the emergency alarm system, designed to give people enough time to escape, did not go off.

Many grieving residents believe that had the warning system worked, far fewer people would have died.

"Those alarms didn’t go off - I’ve never even heard them before," says Geraldo Vilaça from Parque da Cachoeira, which was engulfed by sludge.

Geraldo lost his brother-in-law in the disaster. He, himself, only had three minutes to abandon his house and run.

Vale is Brazil’s biggest mining company and the world’s number-one producer of iron ore. Within Brazil, it produces 80% of the ore for export. In 2017, its revenue totalled $34bn (£26bn; €30bn).

Shortly after the collapse, the company’s president Fabio Schvartsman said at a press conference that the break-up of the dam caused the alarm itself to be “engulfed” by mud.

In a statement later sent to the BBC, Vale said: “The speed of dam breach and the lack of any signs prevented the activation of the emergency system that would have sounded the dam sirens.”

However, Sergio Medici de Eston, professor of mining engineering at the University of São Paulo, rejects this explanation.

“To say that the siren didn't sound because the incident happened so fast is a joke,” he says.

“The alarm should sound when things start to become critical, sometimes weeks ahead so that people are on the alert.”

In the wake of such tragedies, people understandably look for answers.

In Brumadinho, all eyes are on Vale.

But first, people must find their loved ones.

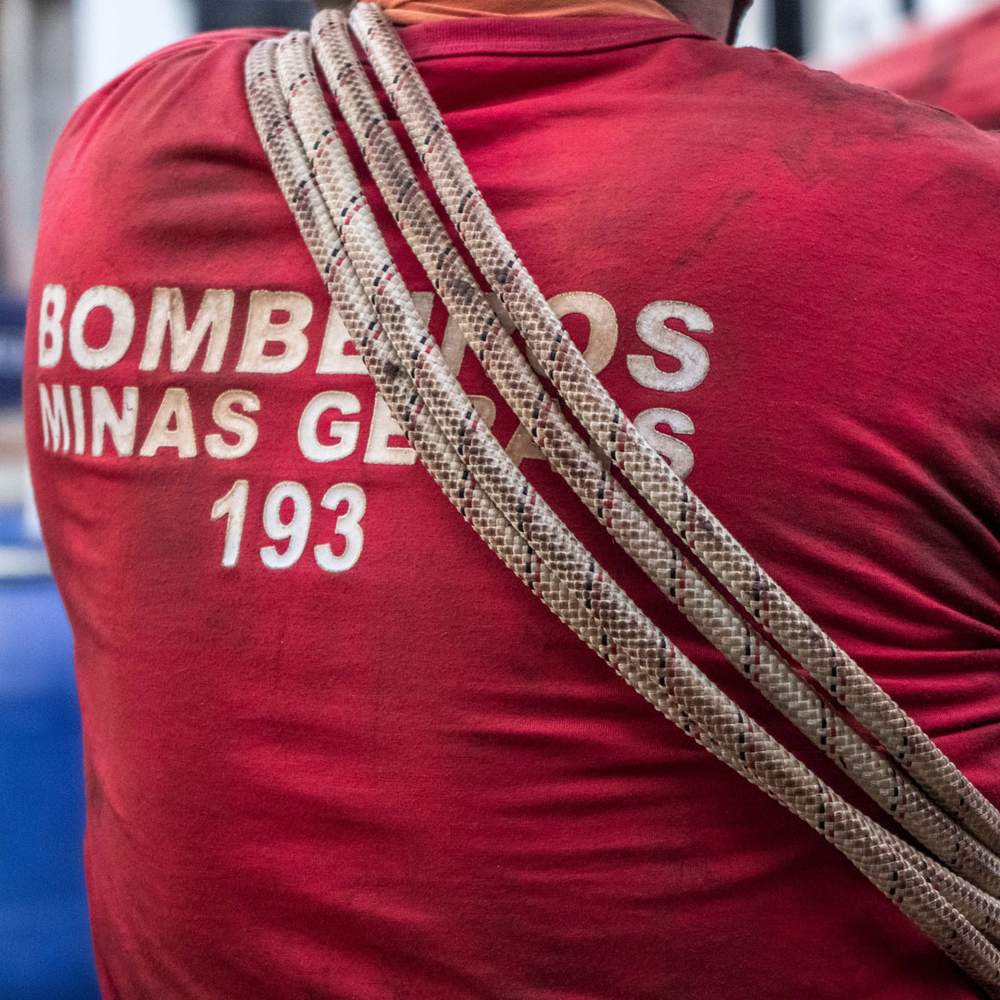

Manoeuvring along the Paraopeba River in an inflatable rescue boat, Eduardo wears a red-and-black neoprene suit and a hard yellow helmet. It’s the distinctive uniform of the “bombeiros”, Brazil’s military firefighters.

Following a report phoned in by two researchers taking samples from the river to measure toxicity, Eduardo scans the riverbank.

Suffocated by the toxic red sludge, the river is dying. Dead fish with open mouths can be seen floating, and even the mosquitoes have dispersed.

Then he sees it - a broken body caught in the riverbank.

With immense care, Eduardo and his two fellow bombeiros lift it into the boat. Clasping a hand in his own, Eduardo is relieved because fingerprints mean the remains can be identified and returned to the family.

The rescue operation is huge. Nearly 400 military personnel, police officers, firefighters and members of the special forces work around the clock in the mud, with the support of helicopters, tractors and sniffer dogs.

In some places, they report working in mud up to 15m deep.

After hours of digging and trudging through the contaminated mud, rescuers are hosed down with a mixture of bleach and antibacterial detergent.

Junior

“I was able to find two bodies today,” says Junior, a young bombeiro waiting in the queue after his shift.

“They were in a very poor condition, as they had started to decompose. But I have faith in God that they will be identified and their families will be able to give them a decent funeral.”

It’s a race against time. Very soon the bodies will begin to decompose fully, and the rescue dogs will be less effective.

Every day, thunderstorms and heavy rain slows the bombeiros’ progress.

“[Rain] hinders the movement of aircraft, reduces the visibility of pilots and may move mud that is still in the dam,” says Lt Gen Anderson Passos, the commander in charge of the rescue operation.

Lt Gen Anderson Passos

The teams must work quickly but carefully. The risk that another dam in the area will collapse is a growing threat.

Just days after the iron ore dam collapsed, the warning alarms rang out for two other dams in the area. Their status was escalated to “at high risk of collapse”. Some 700 people from the surrounding villages were evacuated, while the bombeiros forged on.

Within 24 hours, a special investigation task force had been set up, consisting of both state and federal prosecutors, police, and military.

It was split into three specialities: civil, environmental and criminal.

Overseeing all of this is senior prosecutor for the state of Minas Gerais, Andressa Lanchotti.

Andressa Lanchotti

On the 10th floor of a tall, grey concrete office block in central Belo Horizonte, the nearest big city to Brumadinho, Lanchotti sits in front of a huge whiteboard covered with notes, lists of names and plans to do with the investigation.

“Not for you,” she says smiling, while quickly flipping it over.

Lanchotti is amenable, but straight-talking. The tragedy is all too familiar.

Just over three years ago in November 2015, another upstream tailings dam collapsed killing 19 people. It happened in the same state, close to the city of Mariana, just 75km away from Brumadinho.

More than 50m cubic metres of toxic sludge cascaded into a river and spread all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. It was the worst environmental disaster in Brazil’s history.

The mine's owner Samarco was a joint venture between Vale and Australian-based company BHP.

The aftermath at Mariana

Two months after the tragedy in Mariana, while authorities were still trying to control the spread of mud, the state passed a new law, enabling “fast-track” licences.

This made it easier - not harder - for companies to acquire permits to mine in areas of environmental concern.

In Brazil, and particularly in the mineral-rich state of Minas Gerais, mining lobbyists wield huge amounts of influence and power.

The fast-track licence was the opposite of what Lanchotti and her team had been working on in the aftermath of the collapse at Mariana - a bill proposing stricter laws around the construction and expansion of dams close to residential areas.

“We presented the bid to the local assembly with more than 55,000 signatures of support from the community,” says Lanchotti. “Unfortunately it was not approved.”

Samarco is appealing against a fine of 350.7m Brazilian reais (about $93.5m) for activities resulting in environmental damage.

Manslaughter charges have also been brought against 19 executives from both Vale and BHP Billiton, but the trials have not yet gone ahead.

“The justice system is very complicated,” says Lanchotti. “It’s not just about the prosecutors or judges. It’s also that the system allows numerous appeals, which can delay the final results.”

She reels off a list of problems from a lack of monitoring to political commitment, until finally concluding:

“As long as these issues are not solved, I cannot guarantee that new tragedies like this won’t happen in Brazil.”

Just four days after the breach in Brumadinho, Lanchotti led the task force in making its first arrests - three employees from Vale, and two engineers from German company TÜV SÜD.

These engineers had been hired by Vale to make the regular, legally required safety inspections of the dam, as well as signing off any safety certificates.

A few days after the arrests, Vale’s lawyers had secured the release of all five men.

Then, a little over a week later, parts of the men’s interviews were leaked to the Brazilian media outlet, Globo.

Part of the leak was an email exchange from just two days before the breach, discussing irregular readings on automated monitoring equipment next to the dam.

One of the arrested engineers from TÜV SÜD, Makoto Namba, was asked by police, given those readings, what he would do if his son was working at the site of the dam.

He replied: “After confirming the readings, I would immediately call my son to evacuate the place as well as calling the emergency department at Vale, responsible for triggering the emergency action plan.”

In his testimony, Makoto Namba also said he felt under pressure from a Vale employee to sign off the dam’s safety report back in June 2018. He said he told the employee he would only sign if safety recommendations were addressed.

Both Vale and TÜV SÜD told the BBC they could not comment on the specifics of the investigation until the facts had been verified by the authorities.

An employee of the mine, who asked to remain anonymous, told the BBC that water from a natural spring on a hill above the dam had been seeping on to it. He said a pipe that had been installed at the spring to carry the water away safely had been leaking.

“There was a spring above the dam, but the pipe was broken,” he says.

“The water was falling directly on to the dam. So much so that the middle of the dam was no longer dry. This was more than a month ago.”

Prof Carlos Martinez, an expert on mining dams, says that this would be a reason to immediately evacuate the area.

“This would be unacceptable. Constant water flow coming from a spring would increase the pressure in the dam,” he says.

“The remains of iron ore that exist in these dams normally bond with the sand and prevent water from draining properly. It clogs the filters, it turns it into something similar to a pressure cooker. The area should have been evacuated.”

The Brazilian press has also reported that federal police were investigating suggestions that water might have found its way into the dam from natural springs.

In a statement to the BBC, Vale said: “There was no record of an increase in the water level in the dam mass. On the contrary, the data indicates a reduction in the water level in the main section of the structure.”

For Lanchotti one of the key problems is that big businesses are allowed to self-regulate when it comes to safety and risk management.

“Often the government agencies do not carry out inspections, but instead delegate this responsibility back to the companies themselves, to monitor their own activities.

“Unfortunately, recent events have shown that this form of self-monitoring is simply not effective.”

With just 35 government inspectors for more than 1,000 active and non-active mines across Brazil, most companies hire their own private inspectors to sign off the paperwork.

In the case of Vale, it was the German company TÜV SÜD.

Lanchotti argues that more effective government inspection is needed.

State prosecutor André Sperling is in charge of the civil branch of the investigation.

One of his main jobs is to negotiate with Vale how much compensation should be paid to those who have lost their jobs, their homes and their loved ones.

Since the disaster, he says he has averaged about four hours sleep a night.

André Sperling

“Vale is trying to accelerate the process of paying for damages before the real impact of the disaster has been established. It wants to get rid of the problem as fast as possible,” he says.

While Sperling says that “Vale knew about the risks” he also recognises the conflict felt by both the government and local residents.

This colossal, wealthy company has long been the main source of income for the 37,000 people living in and around Brumadinho. Vale is the biggest employer and taxpayer in the city, and without it, employment, commerce, and even the public sector would come to a standstill.

“We don't want Vale to stop its activities in the state. This would make the local crisis even worse. But they need to pay damages and ensure this never happens again.”

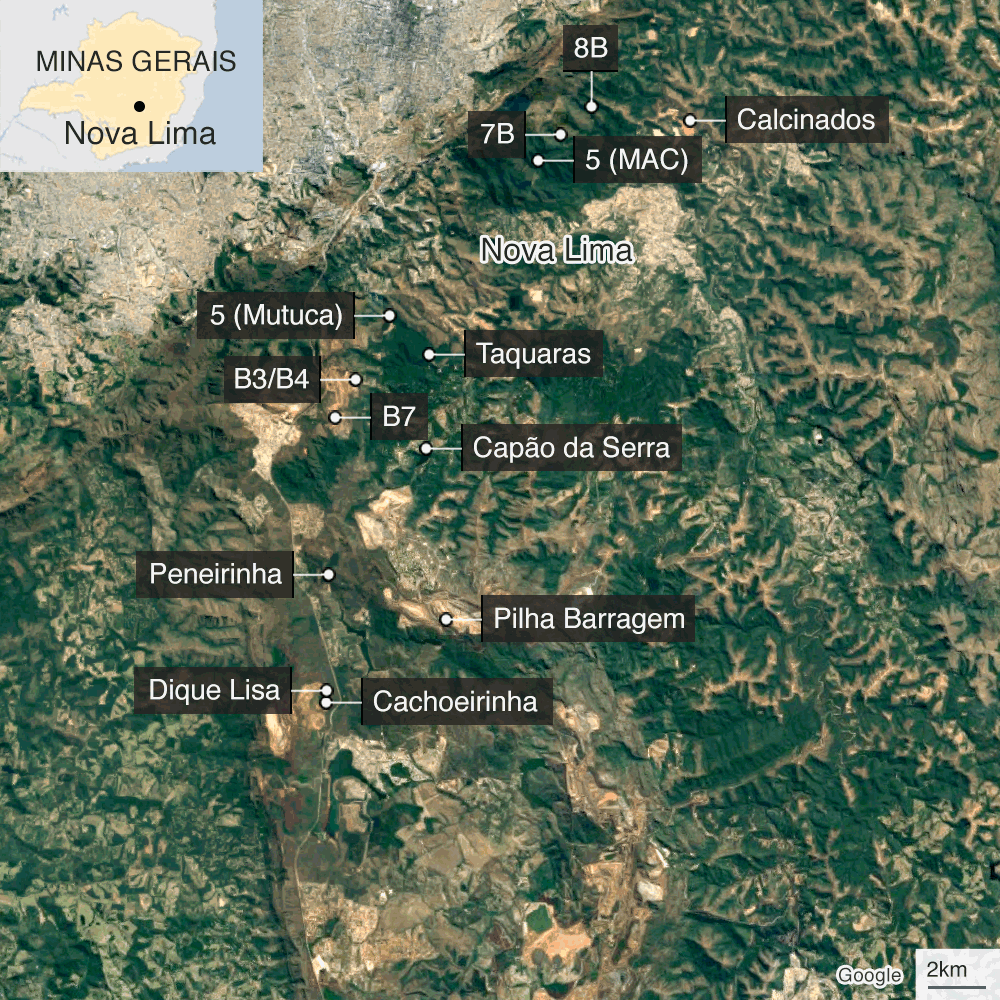

Two weeks after the breach at Brumadinho, sirens rang out in the middle of the night at two other dams in the state of Minas Gerais, warning of a possible collapse.

One, near the town of Barão de Cocais, more than 120km from Brumadinho, is owned by Vale. The other, close to the village of Itatiaiuçu and only 30km away from Brumadinho, is owned by another mining company, ArcelorMittal.

Overnight 700 people were evacuated.

Then, just days later, two more alarms and yet more evacuations within the state. This time from two dams close to the small mining city of Nova Lima, just 40km away from Brumadinho.

In the wake of the tragedy, people all over Brazil have woken up to the vast scale of the problem.

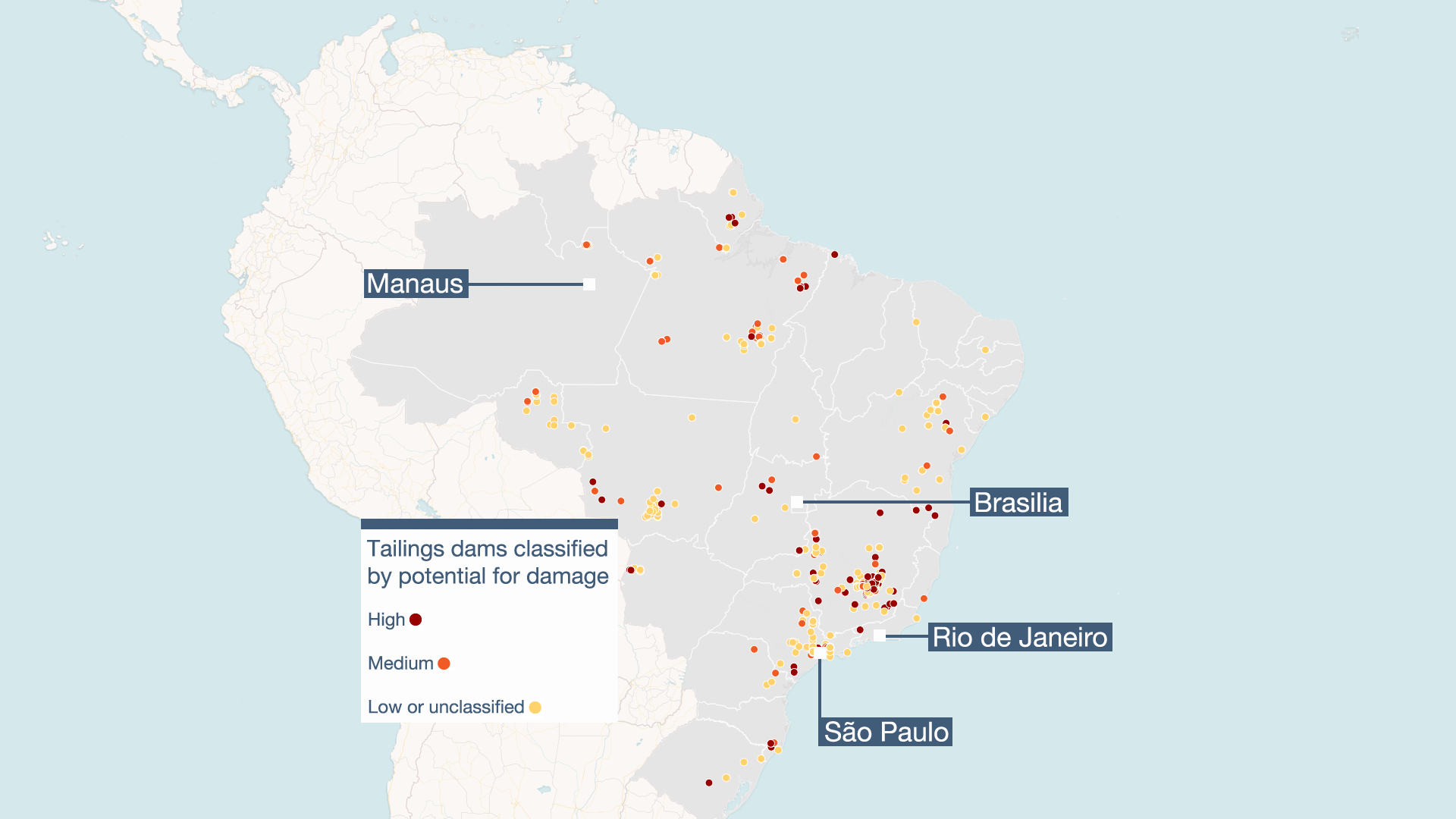

There are at least 790 tailings dams across the country, many of which are directly uphill from towns and cities.

They have all been categorised by their “potential for damage”. This rating scale does not measure how likely they are to collapse, but how much damage they would do if they did.

More than 200 have been classified as “high potential for damage”. It means these dams are either located uphill from a town or a city or are positioned near to a main river or ecosystem.

Both Mariana and Brumadinho were classified as “low risk of collapse” by government inspectors, but of “high potential for damage” because of the number of people living close by, and the potential risk to the environment.

A specialist engineer who was working as part of the recovery operation at Brumadinho and wants to remain anonymous, says that the approach taken by mining companies when assessing risk has long been problematic. He believes anything with a “high potential for damage” should never have been built.

When comparing the mining industry with other heavy industries in which he had worked, he says:

“First you run your worst-case scenario on a computer simulation. Then you design your site around that. For example, on an oil rig, you would locate your offices and sleeping quarters well way from any potential dangers such as a fire or explosions, even if the likelihood of such events is extremely low.”

He points out that in Brumadinho, the offices and staff canteen were sited below the dam.

Vale bought the mine and its offices from another company, but kept the layout of the site.

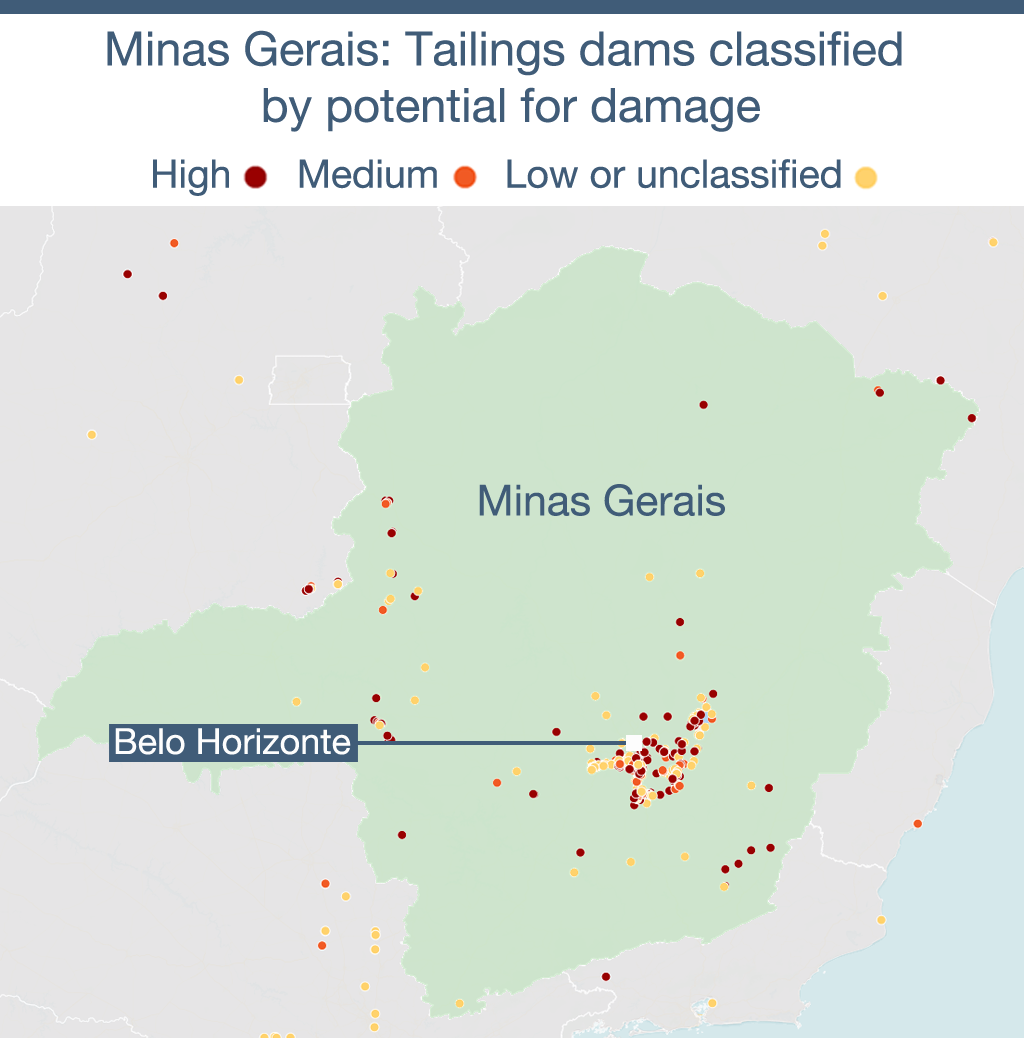

Nowhere in Brazil feels more at risk than the state of Minas Gerais, which produces 53% of the country’s total iron ore output.

Source: Agência Nacional de Mineração (National Mining Agency), Agência Nacional de Águas (National Water Agency). Map created using Carto.

It has more mines and more tailings dams than any other, many of which sit directly uphill from towns or cities.

Nova Lima is one of the three cities partially evacuated late last week after an alarm rang out warning of a possible collapse. The city, which has a population of just over 93,500, is surrounded by 26 mining dams.

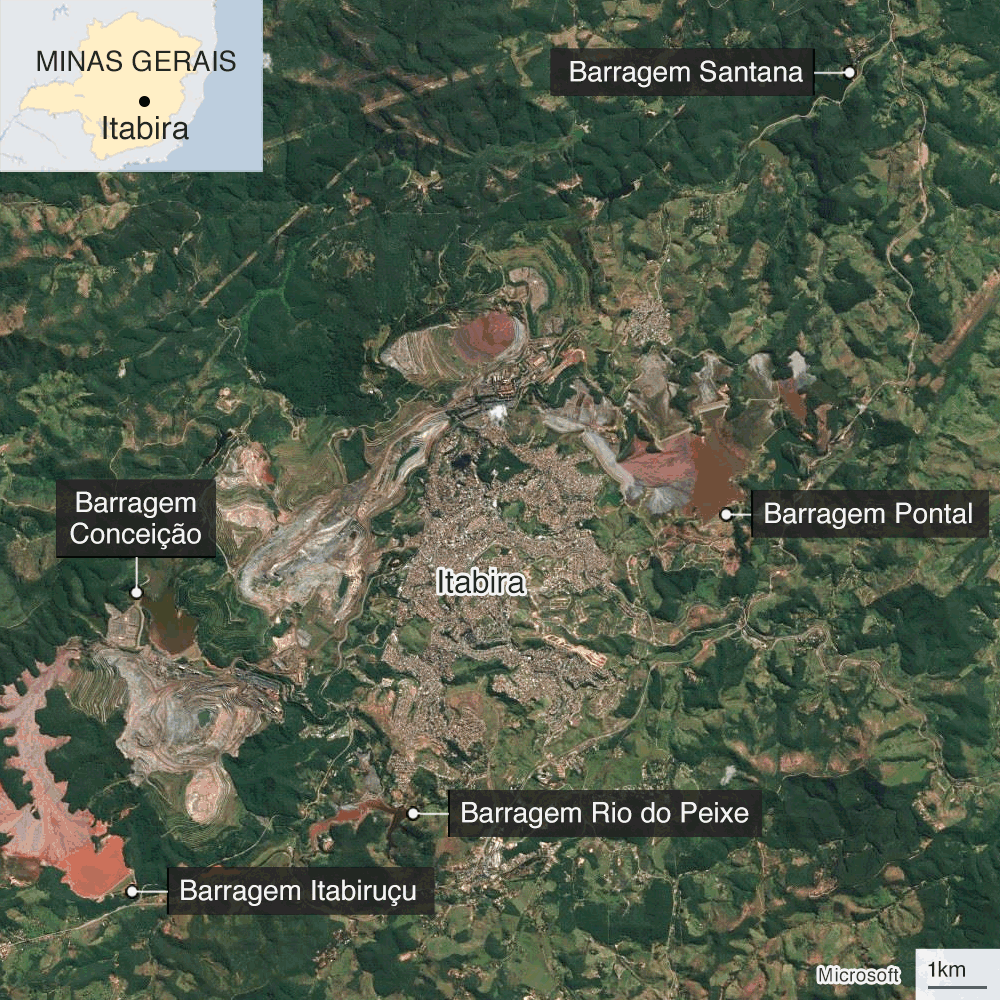

Itabira, where Vale was founded in 1942, has a population of nearly 120,000 and is surrounded by 19 mining dams. In some neighbourhoods, gardens back on to a tailings dam.

The five tailings dams closest to the city hold back a total of 423m cubic metres of toxic sludge. That’s the equivalent of 33 times the amount released last month by the dam near to Brumadinho.

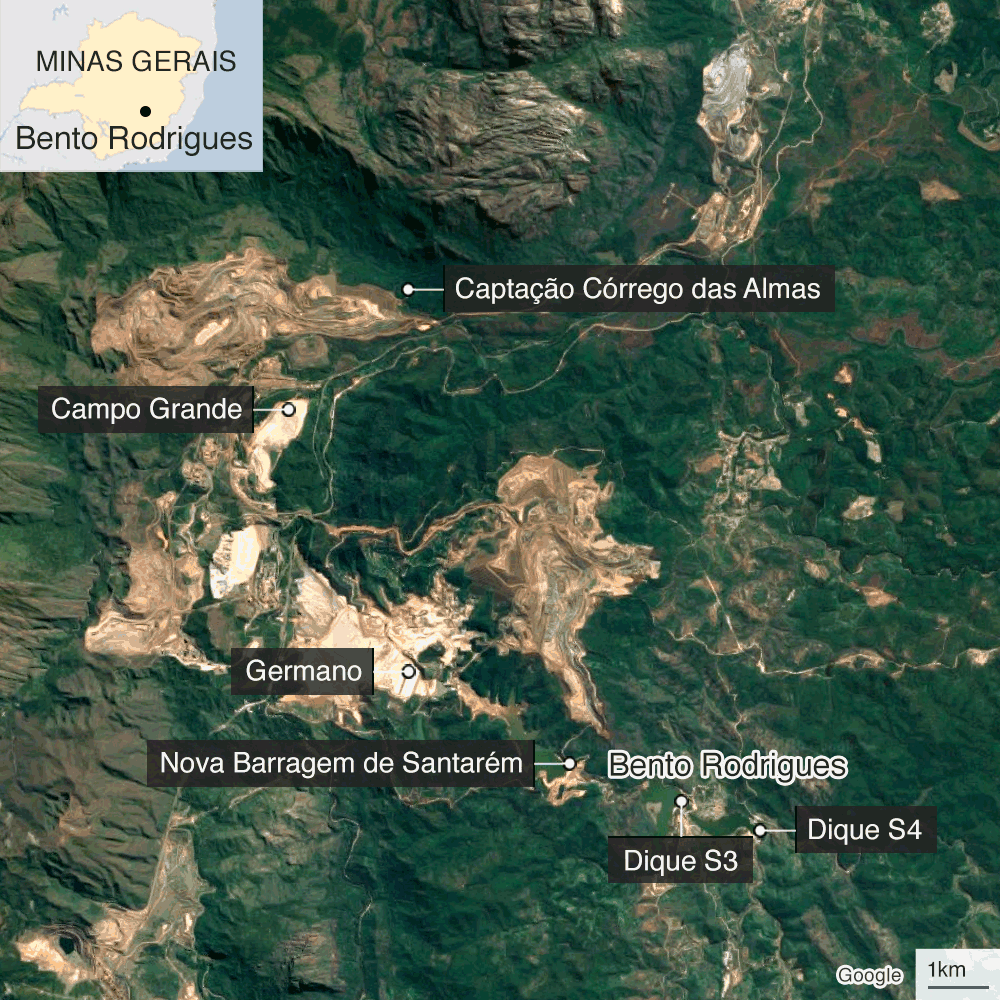

Tragedy struck Mariana in 2015. The city, with a population of 60,000, is surrounded by 15 dams. On its outskirts, in a province called Bento Rodrigues, 600 people live in the shadow of five dams.

While on the campaign trail, Brazil’s new far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, pledged to relax environmental laws, arguing that they “bring endless problems” and “hinder mayors, governors and presidents from developing infrastructure”.

Since the disaster, the government has announced a ban on new “upstream” tailings dams. The 87 that are currently in operation - 10 of them owned by Vale - will be decommissioned by 2021.

But even after a mine is decommissioned, safety inspections must continue, as the waste sludge will sit inside a dam forever.

The government has also said it would put pressure on companies to ensure daily checks are more rigorous.

However, there has been no mention of increasing the number of government inspectors. These daily checks would still rely on the current system, whereby companies effectively monitor their own activities.

“Mariana, never again.” These were the words Vale CEO, Fabio Schvartsman, spoke in a speech to his colleagues on the day he became president of the company in May 2017.

Two days after the disaster in Brumadinho, he promised in a television interview to “guarantee this never happens again”.

For the people of Minas Gerais and state prosecutors, this is not their first attempt at holding Vale to account. They worry that taking on an influential company will be neither quick nor simple.

But, so far, some judges and politicians seem to be listening.

Court orders have already suspended some of Vale’s most profitable operations and frozen 12.6bn reais, or about $3.2bn of the company’s assets.

Late last week, a further eight Vale employees, including two executives, were arrested. Search warrants were also served for four people from Germany’s TÜV SÜD.

Back in Brumadinho, the residents’ fight for justice and the rebuilding of their lives has only just begun.

Under a huge white marquee, erected as part of the rescue effort, more than 400 people are sitting waiting for representatives from Vale to turn up.

For weeks, many of these families have been living in temporary shelters, surviving off ration packs and bottled water, all funded by the company.

Food parcels are distributed to the hundreds of families left homeless

With many local schools still closed, the sound of 30 or more children playing football drifts through from the back of the marquee. A pop-up classroom has been set up by church volunteers offering face painting, a reading corner and a cushioned chill-out space.

For generations, Vale has been the main source of income and stability for the people living in and around Brumadinho. But with more than 300 people missing or confirmed dead, and hundreds more left homeless and jobless, the community’s anger has become inseparable from its grief.

Finally, after nearly an hour’s wait, three representatives from the company appear. But the debate over emergency shelter, food and compensation quickly descends into a shouting match.

“To kill, you are fast,” shouts a woman in the crowd. “You killed my brother in 10 seconds and now you're going to wait how many months to ease what my mother is feeling?”

Vale’s response is business-like:

“At this moment, we can’t take responsibility for something that is still being evaluated. First, we need to understand the extent of the problem,” says one of the company’s representatives. “We do not yet have sufficient information to respond to these requests.”

Weeks later, Vale agreed to pay “emergency income” to families equivalent to the salaries of those who died.

Absent from the proceedings is Brumadinho’s Mayor Avimar de Melo Barcelos. Days before, he told journalists that Brumadinho is a city that “lives off the ore”.

“About 60% or more of our revenue comes from taxes paid by iron ore mining. And most of that is paid by Vale,” he says. “If these payments were to be interrupted after the tragedy, the city would literally stop.

"We have health care units, hospitals, schools, all of which we would not be able to sponsor any more.

“Unfortunately, this is the reality.”

A volunteer sits with one of the many children left homeless

Edmundo Netto Junior is a federal prosecutor working with the investigations task force. He’s spent every day of the past month talking to the families of those who have been confirmed dead, or are still missing.

One of these families included seven-year William, who had tagged along with his aunt.

On the day they met, William had spent the morning painting. In the middle of his picture was a bright blue and yellow rescue helicopter, but dangling from the bottom was a large net - the type used to recover bodies found in the mud.

“He gave this picture to one of the bombeiros [rescue firefighters] and asked them to find his grandfather,” says Netto Junior.

William’s painting also showed a dark red scar cutting through the landscape.

“It’s a community that has been scarred forever,” says Netto Junior.

“It will carry these psychological bruises for life.”

Correction: This story has been amended to reflect that the villages of Córrego do Feijão and Parqueda Cachoeira were not completely destroyed; only some of the houses in the villages were destroyed.