Unveiling: The Law of Gendered Islamophobia

For far too long, “unveiling” has been the subject of imperial fetish and Muslim women the expedients for western war. This Article reclaims the term and serves the liberatory mission of reimagining how Islamophobia distinctly impacts Muslim women. By crafting a theory of gendered Islamophobia centering Muslim women rooted in law, this Article disrupts legal discourses that presume that its principal subjects—and victims—are Muslim men. In turn, this approach lifts Muslim women from the margins to the marrow of scholarly analysis.

Gendered Islamophobia theory holds that state and societal tropes ascribed to Muslim women are oppositional to those assigned to Muslim men. It elucidates how prevailing ideas of “submissiveness” and “subordination” attached to Muslim womanhood, and the grand aim of “liberating Muslim women” that follows, are rooted in an imperial epistemology that caricatures Muslim men as “violent,” “oppressive,” and “tyrannical.” This discourse of “masculine Islamophobia” drives War on Terror rhetoric and policy, and shapes how scholars imagine and then examine subjects of Islamophobia. This scholarly fixation on Muslim masculinity first, isolates Muslim men as the presumptive targets of Islamophobia; second, overlooks the distinct ideas that drive “feminine Islamophobia” and the specific injuries it levies upon Muslim women; and third, perpetuates the erasure of female experiences with systems of Islamophobia from scholarly view.

Beyond unveiling theory, this Article also contributes original empirical data highlighting how Islamophobia differentially unfolds along gender lines. Finally, to illustrate the law’s role in producing gendered Islamophobia, this Article examines six cases within three areas of critical concern: first, hijab bans and state regulation of Muslim women’s bodies; second, terrorism prosecution; and third, immigration and asylum adjudication.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

“The so-called modesty of Arab women is in fact a war tactic.”

—Fatima Mernissi, Scheherazade Goes West[3]

“Let’s win over the women and the rest will follow.”

—Franz Fanon, Algeria Unveiled[4]

A swelling crowd of boys and men raced toward the jet wheeling across the runway. It would be the American plane’s last time rolling atop that Kabul tarmac.[5] And the final time the soldiers within it would step foot in Afghanistan—a nation ravaged by twenty years of American war and military occupation.

A different fate, however, awaited the Afghan boys and men scurrying behind. They, too, dreamt of an escape. Then, upon announcement of the American military’s exit, they scrambled to flee the marching reign of the Taliban.[6] They ran, and ran faster, as the plane bearing the American flag made its way toward liftoff.

Moving in sync with the plane, television cameras honed in on the faces of men clad with traditional turbans and Afghan dress. Some men donned beards, a symbol of Islamic piety, converted into a marker of terrorism since the beginning of the “War on Terror” and its first campaign in Afghanistan.[7] Boys born into war wore looks of frenzy in place of beards as they followed the footsteps of their male elders.

Many in the crowd clung onto the hope that their desperation would invite rescue. They prayed that the “western savior” that descended into Kabul two decades earlier to save their sisters and daughters, aunts and mothers would also return for them.[8] In contrast, those familiar with the sobering truth that only Muslim women get saved clenched onto the landing gear hatches of Air Force Plane 1109 to save themselves.

Seventeen-year-old Zaki Anwari was one of the young men that took matters into his own hands.[9] Five weeks earlier, President Biden had announced immediate plans for the U.S. military evacuation from Afghanistan.[10] Five minutes later, the young man with dreams of soccer stardom and green American fields held tightly onto the plane as it ripped through the clouds. He held and held, until he could hold no more.[11]

Zaki fell.[12] His body plunged from the sky toward the soil he desperately sought to flee. A soil that summoned a War on Terror that targeted him on account of his Muslim masculinity; an identity that invited the global crusade’s harshest indictment.[13] There was no rescue from that cardinal charge of “terrorism,” and no planes to evacuate Muslim men and boys like Zaki.

The Afghan girls landed safely in Mexico City. It was their first time setting foot in the North American nation. However, one would have never guessed that based on the celebrity reception awaiting them.

As members of the celebrated “Afghan Girls Robotics Team,” the five young women were met with hot camera flashes and the warmth of Mexican state dignitaries, who presented the famous evacuees with praise and accommodations.[14] In the days before, the Afghan girls were courted by western governments and White American women.[15] They all stepped in to save the girls for the very same reasons that the Taliban sought to punish them.[16]

The girls were honored residents of Mexico, asylees-in-waiting in the United States, and refugees met with red carpets wherever they went. But most profoundly, they were “victims.”[17] Or so the headlines announced, printed alongside images of their faces veiled by facemasks and draped with loose-fitting hijabs revealing the hair above their foreheads.[18]

Victims, the conjoined popular and political discourse echoed, of a revived Taliban bent on reimposing the burqa and the “barbaric” oppression of women that it—and more potently they—embody.[19] The threat of terror was inextricably tied to the Taliban’s Muslim masculinity, and the markings of savagery and sexism, patriarchy and rage ascribed to their brown bodies. These charges made them—and any Muslim male that fits the description—villains that warrant war, not victims worth saving.

Saving Muslim women, however, was no altruistic mission. While masquerading as a humanitarian or feminist campaign, winning over Muslim girls and women is that ideological tenet of Islamophobia built upon a gendered dialectic of masculine violence and feminine subordination. A gendered binary of victimhood and oppression that positions Muslim women as the former and men as the ominous latter. This potent dialectic reproduces our imagining of Afghan men and boys, like Zaki, as putative terrorists. And, on the other end, spurs our envisioning of Muslim women and girls—like the Afghan Girls Robotics Team—as victims of a masculine Muslim terror, compelling our rescue.

Villains and victims, terrorists and the terrorized are strategic tropes ascribed to Muslims bodies exclusively along gendered lines. These tropes define Western public discourse surrounding Muslims’ lives and form the foundation of a narrative used to justify the War on Terror—a narrative which imposed distinct indictments upon the heads of Muslim women and men. More than twenty years after the beginning of this War, this Article interrogates the gendered anatomy intrinsic to Islamophobia and its attendant discourses. Drawing on critical and feminist theory, this Article then contributes a theory of gendered Islamophobia rooted in law missing from legal scholarship.

Much legal scholarship has examined Muslim women’s experiences over the past two decades within “intersectional” theoretical frameworks.[20] Scholars have used intersectional lenses to analyze foreign policy, counterterrorism, employment discrimination, and other matters of law to bring the experiences of Muslim women into existence. While intersectional approaches generally focus on the convergent spaces of two or more subordinate identities, this Article directly interrogates the gendered dialectic built into standing Islamophobia discourses.[21] This dialectic has been obscured by scholarly fixations on terrorism and resulting theoretical frameworks that distort and erase the genuine experiences of Muslim women.[22]

In response, this Article introduces “gendered Islamophobia” and its attendant concepts into the legal literature.[23] It develops the framework as an analytical tool to examine how potent normative judgments, which spur high stakes legal consequences, are produced squarely from within a cogent discourse objectifying the Muslim female and male bodies. Across law, politics, and academia, this discourse selectively orients the Muslim female and male body along shifting and oppositional situational interests. The discourse is most saliently characterized by a “masculine Islamophobia” which casts Muslim men as the protagonists of terrorism, and a “feminine Islamophobia” which frames Muslim women as their obedient accessories, submissive underlings, and most consequentially, their immediate victims.[24]

By centering Muslim women in the analytical framework, this Article disrupts the male-centric presumptions drawn from foundational Islamophobia theory. It looks within the discursive contours of Islamophobia itself, then unveils the relational dialectic that fluidly produces and reproduces how societal and state actors:

(1) Position Muslim masculinity as oppositional and antagonistic to Muslim womanhood;

(2) Ascribe unique political meaning to Muslim male and female bodies, and normative value to identity markers associated with their respective gender expression; and

(3) Enforce law distinctly across gender lines, particularly within the areas of religious exercise, counterterror policing, and immigration—legal realms where Islamophobia is pervasive and pronounced.

A gendered Islamophobia theory unveils the layered and distinct experiences of Muslim women confronting societal and state-sponsored Islamophobia. Further, to reveal how feminine Islamophobia is shaped by the deeply heterogeneous identities of Muslim women, this Article presents original empirical data derived from a 1,300-subject survey and case analysis that adds flesh to our theory.[25] After all, our gendered Islamophobia theory is rooted in law, and analysis of high stakes cases illustrates the courts’ production and reproduction of it.

In Algeria Unveiled, Franz Fanon offered the trenchant yet sobering observation that “it is . . . the plans of the occupier that determine the centres of resistance around which a people’s will to survive becomes organized.”[26] These predetermined “centres of resistance” are both physical and intellectual, illustrated by the first and subsequent waves of Islamophobia theory that centered Muslim men as the presumptive victims of state and societal violence.[27] This Article builds on formative postcolonial theory, feminist theory, and contemporary Critical Race Theory, and by reclaiming Unveiling in our very title, it confronts the imperial literatures that have caricatured the hijab as oppressive and the women who don it as victims of Muslim men. By positioning Muslim women at the center of this new language of resistance, Unveiling contests Islamophobia at the very imperial roots that gave rise to bygone conquests and modern culture wars.

This Article will proceed in three parts. Part I surveys standing theories of Islamophobia within and beyond the legal literature. It then proceeds to outline “gendered Islamophobia,” a novel theoretical framework that centers Muslim women within legal literature. Part II presents empirical data focusing on the public imagining of Muslim manhood and womanhood. It contributes original data sets that measure the gendered dimensions of private Islamophobia and distill how Muslim female and male identity are publicly imagined and understood. Part III turns its attention to the law. It examines how legislation and court decisions distinctly impact Muslim women in three areas of critical Muslim concern: hijab bans and policing of religious freedom, terrorism prosecution, and immigration and asylum adjudication.

I.

Theorizing Gendered Islamophobia

“The imagined terrorist isn’t me,” the veiled Muslim audience member stated. She then pointed to the young man seated to her right, “It’s my son, and the [Muslim] men that we live with.”[28] The woman’s son looked downward as the room’s collective eyes caved inward, simulating the theatre of suspicion surrounding Muslim men and boys everywhere the War on Terror left an imprint.[29]

That presumption of terrorism, his mother emphatically revealed, was not assigned to her—a middle-aged Muslim mother of two, who donned the headscarf and spoke impeccable English. Rather, it was a gendered presumption specifically tied to masculine Muslim identity. Muslim women, like the woman standing before us inside the Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia, stood at the margins of how society, and perhaps the state, imagined the corporal form of the terrorist. In response to this imagining, standing Islamophobia theory reproduced frameworks presuming Muslim male violence in line with the audience member’s revelation, and critical scholars challenging the terrorist caricature tended to privilege Muslim male victimhood.[30] By centering the Muslim male and masculinity on both ends, standing Islamophobia theory created inflexible frameworks that marginalized and erased the genuine experiences of Muslim women and, oftentimes, confused and conflated them with the experiences of their sons and brothers, husbands and fathers.[31]

This Section interrogates these Muslim male-centered theories on Islamophobia. It then builds upon them—and the postcolonial, feminist, and critical race theory theoretical traditions that orbit them—by contributing a gendered Islamophobia theory into legal and interdisciplinary literatures.

A. Formative Theories

A critical point of departure is to acknowledge that formative Islamophobia theories, which exclude gender from their analytical structure, remain functionally gendered. Omitting an explicit gendered analysis assumes that the standard is the male experience, regardless of whether the subject in question is racism, the reasonable prudent person standard, or in this case, Islamophobia.

1. Reorienting Islamophobia Theory

Standing Islamophobia theories, which isolate the Muslim subject as the imagined purveyor of terror threat, marshalled longstanding Orientalist tropes assigned to Muslim men. As Edward Said’s master discourse established, the “Orient”—or the Muslim world—is imagined as wicked and war-torn, backwards and bereft of civility.[32] This essence of violence is most intimately tied to an innate patriarchy, where Muslim men are enforcers of a domestic and trans-civilizational violence.[33] The latter, manifested by modern threats of terrorism, is reserved for Western nations and actors, while the former is reserved for their immediate targets of subordination, Muslim women.

These longstanding Orientalist tropes centering this double-pronged violence are narrowly tailored to the imagining of Muslim male threat. Women, in the Orientalist imagination, are seldom understood as standalone subjects of threat or violence.[34] Rather, they are targets of masculine Muslim violence. Despite this gendered Orientalism and its epistemological “redeployment” during the War on Terror, formative theorizing of Islamophobia built upon uniquely masculine Muslim tropes of threat and violence, broadly applied across gender lines.[35] Consequently, male-centric conclusions were imposed upon women and girls, who experienced Islamophobia in dramatically distinct ways from their male counterparts. This was true on a domestic level, but also transnationally as Islamophobia expanded and adapted as a fully global phenomenon.[36]

Feminine Orientalist tropes assigned to Muslim women were largely ignored.[37] In turn, Muslim women were unaccounted for in the formative Islamophobia theories preoccupied with terrorism and the imagined Muslim male terrorist. This masculine crafting of Islamophobia theory pervades scholarship across disciplines, and most intensely within the law.

2. Legal Theory

Within legal scholarship, early literature on the “racialization” of Muslims during the War on Terror centered terrorism as the locus of Islamophobia.[38] In the widely cited piece The Citizen and the Terrorist, law scholar Leti Volpp concluded that “September 11 facilitated the consolidation of a new identity category that groups together persons who appear ‘Middle Eastern, Arab, or Muslim.’ This consolidation reflects a racialization wherein members of this group are identified as terrorists and disidentified as citizens.”[39]

The racialization of Muslims thesis, and accompanying theory, pervaded critical legal scholarship that proliferated in the wake of 9/11. Analogizing Muslims to the interned Japanese population circa World War II, law scholar Natsu Saito echoed Volpp: “Just as Asian Americans have been ‘raced’ as foreign, and from there as presumptively disloyal . . . Muslims have been ‘raced’ as ‘terrorists’: foreign, disloyal, and imminently threatening.”[40]

Through a Critical Race Theory lens, Volpp and Saito initiated a vital canon on the racial reimagining of terror threat during the earliest stages of the War on Terror.[41] This racialization of terror threat, oriented as oppositional to citizenship and whiteness, reflected the state and societal fears centrally associated with Muslim men.[42] As police dragnets interrogated droves of Muslim male subjects and Guantanamo evolved into an all-male prison, the American war to “liberate Muslim women” simultaneously raged onward in Afghanistan, Iraq, and deep within Muslim American communities.[43] This “first wave” War on Terror scholarship captured how law forcefully shaped the racialization of terror threat and gave form to the phenomenon of Islamophobia.[44] Critical Race Theory, which centers race as the locus of inequality and focus of state violence, proved a natural vehicle for formative theorizing on Islamophobia as the War on Terror took form.

The subsequent wave of scholarship introduced new frameworks to challenge state and societal animus toward Muslims. Law scholar Sahar Aziz’s work filled voids in the War on Terror canon by making the distinct experiences of Muslim women visible.[45] Aziz observed, roughly a decade into the War on Terror, that “most of the discussion focuses on the experiences of Muslim men or analyzes law and policy through a male gendered paradigm.”[46]

Building in part on Aziz’s work, and focusing on terrorism as a theoretical crux, law scholar Khaled A. Beydoun offered an analytical model that isolated “private” Islamophobia—that is, private modes of anti-Muslims behaviors—from “structural” Islamophobia, the propagation of anti-Muslim policies and outcomes by the state.[47] This new framework, which theorized the fluid and often violent “dialectic” between state law and societal violence against Muslims (and perceived Muslims), situated the law as the principal spearhead of Islamophobia.[48]

While most scholars look beyond the analytical contours of Islamophobia by applying frameworks such as feminist theory and intersectionality in their work, this Article looks within standing Islamophobia theory itself to consolidate a theoretical framework where gender, and womanhood, is central to the law’s reproduction of it.[49] This Article’s gendered Islamophobia theory does not seek to supplant existing analytical models that prioritize race and racialization or distinguish state-sponsored from private forms of Islamophobia. Rather, it builds upon them and engages directly with frameworks that distinguish how state and private actors perpetuate Islamophobia.

Subsequent legal theories build upon a model which racializes Muslims, and in turn, perpetuate the presumption of Muslim masculinity. Law scholar Caroline Mala Corbin, for example, oriented this racialization of terrorism against the exculpatory power of whiteness, observing how “terrorists are always Muslim but never white.”[50] The lack of a central definition of terrorism enforces it upon those (Muslim men) who fit the imagined profile, and subverts application to culprits racially disconnected from it (White men).[51] These trenchant critiques are vital to challenging the indemnifying effects of whiteness and the presumptions of guilt that comes with being raced Muslim. In addition, the interrogation of Islamophobia in relation to whiteness connects contemporary discourses to formative periods of American history when whiteness stood as a prerequisite for naturalized citizenship and Islam oriented as inimical to it.[52] The orientation of Islam as antithetical to whiteness extended Orientalist understandings of Muslim identity into the War on Terror context.[53] This framing also redeployed masculine narratives that relegate Muslim women to secondary or invisible victims, while also overlooking how they uniquely experience the injury that arises from within the inherent contours of Islamophobia.[54]

3. Islamophobia and Empire

The theoretical presumption of Muslim masculinity pervades theoretical projects on Islamophobia beyond the law. In Islamophobia and Racism in America, sociologist Erik Love adopted the racialization framing pioneered by law scholars Saito and Volpp, writing, “[a]nyone who racially ‘looks Muslim’ is similarly vulnerable to Islamophobia. Many South Asian Americans are Muslim, but many others are Hindu, Sikh, Christian, Buddhist, or have no religion at all.”[55] Love continues to define Islamophobia as the progeny of American racism, rooting it in white supremacy and situating it within “the full scope of American race and racism.”[56]

Love’s theoretical pivots are instructive on two fronts. First, his definitional scope is limited to the United States and the cultural and political reach of American racism and policy.[57] Second, despite this confined scope, Love provides a rich racial analysis that dislodges Islamophobia from a dominant terrorism framing. While central to his treatment, terrorism stands as one of many prisms in which Muslim identity is racially imagined, stigmatized, profiled, and policed. Terrorism is salient, but not solitary.

Gender, and specifically the experiences of Muslim women, are not explicitly built into Love’s Islamophobia framing. However, its dislodging of terrorism as the theoretical marrow enables an interrogation of gendered Islamophobia without the weight of privileging masculine Muslim tropes. As Love’s theory conveys, Islamophobia assumes explicit racialized forms when performed through private Islamophobic acts. This framework not only centers the experiences of Muslim women but also mobilizes academic and empirical interventions toward an imperial framing where gender is foundational.[58]

Media scholar Deepa Kumar’s theorizing of imperial Islamophobia returns it back to its Orientalist roots. She writes that Islamophobia “is best understood, in its myriad and ever-changing manifestations, as rooted in empire. Thus, Muslims’ inclusion within an imperial system that presides over war, genocide, and tortures does little to dent racism.”[59] Rooted in European and American empire, the modern War on Terror remakes and pronounces Islamophobia to ominous proportions.

By interrogating Islamophobia beyond American boundaries, both geographic and legal, Kumar’s Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire traces her analysis back to the postcolonial period.[60] This point of commencement is critical on four fronts. First, it reconciles Islamophobia, and the understanding of it, with the very gendered ideas, images, and narratives of its maker: Orientalism. Orientalism, after all, is the mother of Islamophobia, and any analysis of the latter must be prefaced with discussion of the former. Orientalism was an imperial project, and Islamophobia a pointedly “neocolonial” American project propagated by its War on Terror.[61]

Second, by returning to its epistemological roots, Kumar removes the War on Terror as the focal prism anchoring Islamophobia theory, and frees the imagining of Muslim subjects, principally women, through the masculine prism of terrorism.[62]

Third, Kumar draws on foundational feminist texts, particularly those writing within the humanities and social science spheres, to craft her imperial framing of Islamophobia. These literatures, as landmark Muslim feminist Fatima Mernissi observed, dislodge the trope that reduce Muslim women into flatly submissive beings lacking agency and individuality.[63]

Fourth, Kumar’s work affirms the centrality of media studies to this area of inquiry. Edward Said himself followed the discourse’s foundational text, Orientalism, with Covering Islam, an indictment of the mainstream media’s lead role in producing and disseminating misrepresentations of Muslims.[64] By doing so, Kumar highlights the “Islamophobic dialectic” tying media stereotype-production with state action.[65] This observation is echoed by media scholar Evelyn Alsultany and political scientist Nazita Lajevardi, who find that “newspaper coverage over 35 years reveals that stereotypes as a cultural threat have been consistently perpetuated by tying together themes of Muslim women and gender inequality.”[66]

Moreover, an imperial framing of Islamophobia crystallizes how European and American empires imposed rigid gender binaries (and accompanying ethnocentric narratives) upon Muslim-majority populations. Many Muslim-majority societies envisaged gender along nuanced, complex lines, and represented gender roles in forms that conflicted with the Orientalist reimagining of Muslim womanhood. Reflecting on this latter point with regard to European media, Mernissi observed, “In both miniatures and literature, Muslim men represent women as active participants, while Westerners such as Matisse, Ingres, and Picasso show them as nude and passive. Muslim painters imagine harem women as riding fast horses, armed with bows and arrows, and dressed in heavy coats . . . But Westerners, I have come to realize, see the harem as a peaceful pleasure garden where omnipotent men reign supreme over obedient women.”[67]

Framing Islamophobia as an imperial project flips analytical scrutiny from the Muslim subject toward the colonial actor, or in the modern context, the state. The advancement of empire, in former colonial campaigns and the neocolonial aims of the War on Terror today, shifts analysis onto the state and its weaponization of race and racism, sect, and, most violently, gender.[68] All were tools wielded to demonize, divide then conquer Muslim men, then subsequently “save” Muslim women from a Muslim masculinity menacing women at home and Western “civilization” from afar.[69]

The War on Terror, far from being the starting point, is the modern manifestation of that venerable campaign to discipline and destroy Muslim-majority societies. Islamophobia theory, as Kumar, Hamid Dabashi, Beydoun, and others contend, must interrogate the epistemological crusade against Muslims seeded centuries before Islamophobia was given its modern name.[70] By contributing a cogent theory of gendered Islamophobia into the legal literature, this Article builds on these works and the postcolonial pioneers that laid the intellectual foundation to combat Orientalism, Islamophobia, and their collateral forms and fronts.

B. Gendered Islamophobia

The War on Terror thrust the term “Islamophobia” into popular and political parlance. But it did not spawn the phenomenon of anti-Muslim violence. Likewise, the modern terrorist caricature exists as the contemporary embodiment of longstanding anti-Muslim “othering,”[71] or what the postcolonial scholar Aimé Césaire called “thingification.”[72] Yet, understanding this masculine manifestation of Muslim demonization requires retheorizing at the very root of Islamophobic empire and its attendant forms of othering. These roots, not coincidentally, are pointedly patriarchal in motive and mandate.

Dissecting the anatomy of the French colonial mission in Algeria and the Francophone Maghreb at large, Fanon observed,

In the colonialist programme, it was the women who was given the historic mission of shaking up the Algerian man. Converting the woman, winning her over to the foreign values, wrenching her free from her status, was at the same time achieving a real power over the man and attaining a practical, effective means of de-structuring Algerian culture.[73]

Islamophobia, in its initial Orientalist makeup, did not center the Muslim man as the principal figure of conquest. Rather, it—and its most violent past and present campaigns—isolated the Muslim woman as the focal subject of profiling and policing, conversion and conquest. Liberating Muslim women, after all, would create avenues for dispatching her sons, brothers, fathers, husbands, and ultimately, conquering the land.[74] Or, as Kumar notes, this mode of feminist “liberalism in service to empire became a shield behind which racism was hidden,” and wars were legitimized.[75]

In line with these origins, this Section builds on standing Islamophobia theory by unveiling a gendered framework that not only centers Muslim womanhood, but situates it as the very heart of a novel framework and language to interrogate Islamophobia moving forward.

1. A Theory

Gendered Islamophobia is the strategic orientation of Muslim women as both the object of imperial saving and the subject of Muslim male violence. It is a relational dynamic and dialectic, whereby the contours of Muslim womanhood are shaped in opposition to the construction of Muslim masculinity. The imagining of Muslim men as tyrannical, violent, and terroristic produces the image of Muslim women as oppressed, powerless, and submissive and, consequently, the immediate victims of masculine Muslim violence. This form of violence, in the gendered Islamophobic imagination, spurs the rhetoric of “saving Muslim women” that beats the drums for war and fuels the punitive state action examined in Part III.

This characterization situates the Muslim female body at the crosshairs of convergent aggression. Further, gendered Islamophobia places the Muslim woman at the intersection of Muslim male violence and western savior campaigns, denying her agency and purporting that freedom can only be attained through its laws, intervention, or war.

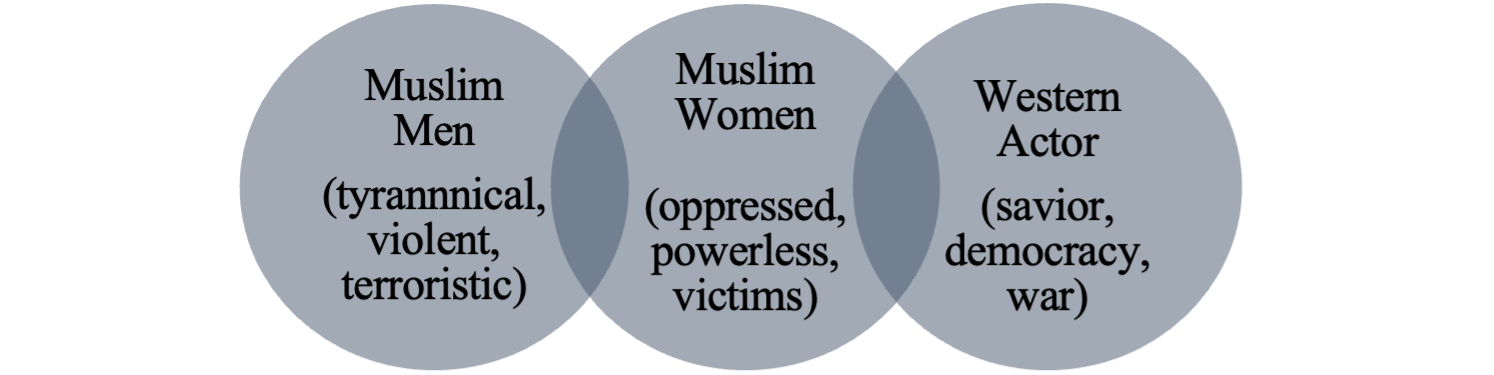

Figure 1 | These overlapping circles illustrate the imagining of Muslim women, interlocked between masculine Muslim violence and the western rescue campaign.

By centering Muslim women, a gendered Islamophobia theory distills the distinct tropes assigned to Muslim women and men by state and private actors. Subsequently, it unveils the theoretical fixation on masculine Muslim terrorism gripping existing Islamophobia theory and legal scholarship.

Applying a legal framing of Islamophobia, this Article echoes that law functions as the most potent catalyst of gendered Islamophobia. Here, we frame the law broadly as executive action, judicial ruling, legislation, and other forms of state action, including war.[76] We delineate “private feminine Islamophobia” and “private masculine Islamophobia” as the “fear, suspicion, and violent targeting of Muslim [women and men, respectively] by individuals or private actors,” such as bigots or hate groups.[77] The state, as Part III reveals, is the spearhead of Islamophobia. With that, this Article adopts “structural feminine Islamophobia” and “structural masculine Islamophobia.”[78] These forms of animus are defined as “the fear and suspicion of Muslim [women and men] on the part of institutions—most notably, government agencies—that is manifested through the enactment and advancement of policy and law,” such as hijab bans, travel bans, and surveillance programs.[79]

Gendered forms of Islamophobia, inflicted by private and government actors, are fused together by an ongoing “dialectic.”[80] State actions, most notably policies that explicitly associate Muslims with terrorism, have a discursive effect of materially shaping popular views.[81] Through original survey data, Part II unveils how the discursive effect of this War on Terror dialectic splinters along gendered lines.

2. Between “Liberation” and Subordination

Islamophobia, if anything, is an imperial tool wielded to legitimize violence. This end does not play out monolithically but is determined by the gendered identity of the specific targets of violence. The global and domestic theaters of the War on Terror speak to this shifting form of Islamophobic violence, particularly with regard to the most fetishized marker of Muslim identity: womanhood.[82]

The shapeshifting character of Islamophobia was on full display in Afghanistan after the 9/11 terror attacks. Two months after President George W. Bush formally announced the global war on terrorism, first lady Laura Bush presided over another performance of that war.[83] During a globally telecasted radio address, Laura Bush lobbied,

Only the terrorists and the Taliban forbid education to women. Only the terrorists and the Taliban threaten to pull out women’s fingernails for wearing nail polish . . . Civilized people throughout the world are speaking out in horror, not only because our hearts break for the women and children in Afghanistan but also because, in Afghanistan, we see the world the terrorists would like to impose on the rest of us.[84]

The War on Terror, during its infancy, also became a crusade to save Muslim women. In Laura Bush’s words, “the fight against terrorism is also a fight for the rights and dignity of women.”[85] This was a moral imperative for war, buoyed by a feminist mandate, no less.[86]

But who were these Muslim women being saved from? This gendered Orientalist binary, reproduced by executive rhetoric, isolated Muslim men as purveyors of violence and a terrorism that threatened western civilization, security, and Muslim women.[87] The War oriented Muslim women as both the common target of Muslim men and as a means of disarming critics to galvanize support where male terrorists threaten Muslim women: Afghanistan, Iraq, and spaces both American and foreign.[88] Feminist scholar Gayatri Spivak’s characterization of imperial patriarchy captures the gendered and racial essence of the War as “white men [joined by white women] saving brown women from brown men.”[89] Spivak, much earlier, exposed the propaganda campaign driving gendered Islamophobia. Namely, that Muslim women needed saving from their most intimate partners and countrymen.

Adapting Spivak’s insertion of race and racism, the campaign to save Muslim women served as a western feminist campaign, outwardly led by White women but functionally spearheaded by White men. Liberal feminism and its cadre of famous women advocates provided a Trojan Horse for Halliburton,[90] Huntingtonian “civilizational clash,”[91] and the overwhelmingly male neoconservative brain-trust that plotted a new order of hypermasculine American empire.

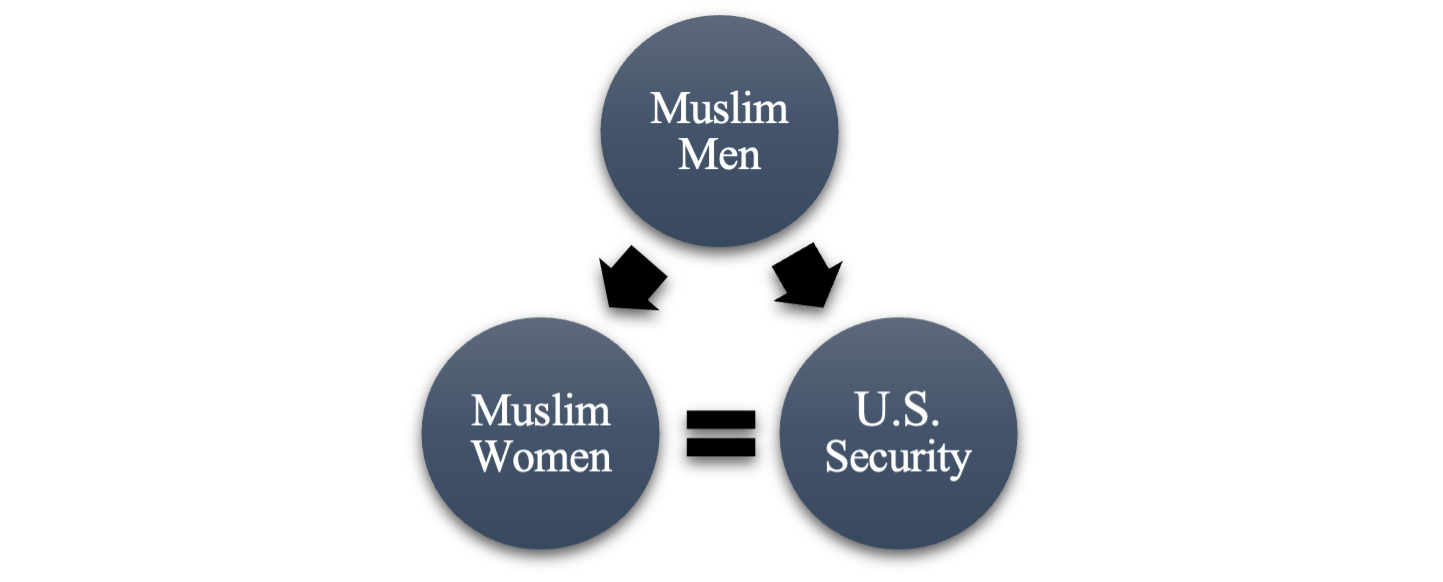

Figure 2 | Muslim women and American national security are oriented as the common victims of masculine male terrorism. The arrows represent the purported violence inflicted by Muslim men, while the equal sign represents its common targets.

Moreover, the crusade to save Muslim women not only legitimized distant wars but also enabled surveillance within the most intimate realms of Muslim life.[92] Because the War on Terror branded husbands, brothers, sons, and uncles as putative terrorists, the preemptive and punitive reach of the War on Terror extended into living rooms and bedrooms, homes and mosques, and, even more piercingly, the woman’s corporal body.[93] Further, as Muslim men were rounded up for security interviews in the United States or gunned down on foreign battlefields, the Muslim woman’s body—the object of rescue—functioned as the battleground between Muslim men and Western men.

A gendered theory unveils how this mandate of “saving Muslim women” is built upon an intricately gendered Islamophobic dialectic. First, the three-word crusade is carved from the masculine Muslim tropes of violence, patriarchy, and tyranny. These tropes not only characterize the posture of Muslim men toward their wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters, but far more deeply, they define the very culture of the lands that they come from. There was no War on Terror charge to save Muslim boys or elders, who, despite age or innocence, were still seen through the masculine prism of terrorism.

Second, saving Muslim women strips them of their agency and perpetuates the entrenched tropes of dependence, passivity, and powerlessness. The gendered Islamophobic gaze observes Muslim women through the prism of masculine male violence, incessantly vulnerable to his violence and forever bonded to his tyranny.

Third, because the Muslim woman is circumstantially or intrinsically incapable of freeing herself, according to the Islamophobe, the American or foreign actor is left with no choice but to intervene. This Islamophobic savior complex, rooted deep in Orientalist and colonial discourses, drives prominent state figures, like Laura Bush and Cherie Blair, and private organizations, such as the American Feminist Majority Foundation, to flank themselves alongside their militarized, male counterparts and beat the drums for war.[94]

Saving Muslim women, thus, is the gendered Islamophobic bridge justifying the global and domestic tentacles of the War. Again, as scholars within and beyond the law have observed, this is a foundationally racialized discourse.[95] The reification of Muslim men as the culprits of terrorism and Muslim women as the direct victims of that terror is an intensely gendered discourse. Through its blanket “threat of terrorism” framing, standing Islamophobia theory, independent of a gendered dimension, cannot unveil the distinct caricaturing and violence it inflicts on Muslim women.

Saving Muslim women is uniquely, yet unmistakably, violent. This violence is driven by Islamophobic myths coloring Muslim men as prone to terrorism and western warmongers as innately democratic and altruistic. However, the bombs dropped in Afghanistan and Iraq and the drone attacks in Yemen and Somalia do not distinguish between the gender of their targets. Further, even if military violence wrought by counterterror campaigns were disproportionately inflicted upon Muslim men, widowed wives and fatherless daughters would still be left to endure collateral forms of violence shattering their lives. They would face poverty, foreign occupation, sexual violence, and, perhaps the most penetrating form of feminine Islamophobia, the ongoing regulation of their bodies via headscarf bans and free exercise of religion restrictions disproportionately burdening Muslim women. The western crusade to save Muslim women veils a reality where they were being indirectly and distinctly punished.

After all, the War in Afghanistan and the broader War on Terror neither saved nor liberated Muslim women en masse. Despite the token rescue of exceptional Muslim women, the American war and occupation claimed more lives of Afghan women and girls than the Taliban—the very group that pulled the American military into Afghanistan, and twenty years later, sent them packing.[96]

3. Unveiling Tropes and Truths

Through patriarchal discourses, womanhood is materially shaped through an understanding of men. As such, men make women and how they are perceived by the world. This is particularly true when the subjects are Muslim women who have been fluidly reimagined and reconstructed through the lens of imperial masculine handlers, through art, political narrative, literature, and law.[97]

Orientalists and their Islamophobic progeny color “Islamic culture” as unbendingly patriarchal.[98] When Trump proclaims, “I think Islam hates us,” the public imagines Islam in a menacing male form, who directs their distant ire on the American “homeland” and the Muslim women within arms’ reach.[99] These Muslim women, in the public Islamophobic imagination, are controlled by men and perpetually vulnerable to their violence. Bent on making women in their imperial image, these imperial discourses are themselves guilty of reconstructing Islam as innately patriarchal.[100]

Islamophobic policy continues as a principally male-led enterprise today. Its principal thinkers, led by the likes of Bernard Lewis and Samuel Huntington, are predominantly men. Its governmental and geopolitical stewards —Donald Trump, Emmanuel Macron, and Narendra Modi—are also overwhelmingly men. Its most influential propagandists and pundits, such as Sam Harris or Eric Zemmour in France, are overwhelming men. While women like Laura Bush and Marine Le Pen drive damaging Islamophobic policy and talking heads like Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Pamela Geller peddle harmful propaganda, these women are novel abettors of a crusade made and helmed by men, specifically White men.[101] This is especially true for the law, where White men dominate federal judgeships and preside over cases that determine the lives of Muslim women.[102]

What effect does this patriarchal making of Islamophobia have on the construction of Muslim men, and women in particular? Scholars and pundits have written extensively about the categorical objectification of Muslim women as victims.[103] Victims that, as articulated above, are in dire need of rescue from the very Muslim male terror that threatens western security and civilization.

This objectification, however, is twofold. Beyond this heuristic stands the reciprocal veiling of Muslim women as a deeply diverse population that worship, look, and live differently. This flattening, as the gendered Islamophobic dialectic reveals, is not unique to Muslim women. Prevailing Islamophobia theory tethered to terrorism speaks to the gendered suspicion assigned to Muslim men and over the last decade has inspired critical rebuttals that challenge the terror tropes assigned to Muslim men and boys. Yet, these theories stifle cognition of how Muslim women who deviate from the “master terrorist caricature” distinctly experience private and state-sponsored Islamophobia. Moreover, the masculine terrorism framing is frequently wed to religious conservatism or “Islamic extremism,” which reproduces the flattening of Muslim women as the target and the oppressed—imprisoned by her male lord and his veil. [104]

4. Not All Muslim Women Veil

In the mind of the Islamophobe, the Muslim female object is always veiled. She expresses her identity through some form of veiling—hijab, niqab, chador, and, most in line with the feminine trope of subordination, burqa.[105] In the eyes of the Islamophobe, these iterations of Islamic covering determine the degree of subordination and gravity of oppression. As Fanon describes the Islamophobic gaze vis-à-vis the veil, “With the veil, things become well defined and ordered. The Algerian woman, in the eyes of the observer, is unmistakably ‘she who hides behind a veil.’”[106] Unveiling, in its imperial form, is that process of revealing the individual behind the article not for her own liberty, but for the sexual or political conquest of the western male who removes it.

While Muslim men are viewed for their propensity for violence, Muslim women are judged by their relationship with the veil. This latter link is inextricably tied to masculine Muslim domination, given that Muslim men are viewed as the imposers of the veil. Muslim women are understood, made, and remade through the single-axis epistemic of veiling. After all, “[c]olonialism wants everything to come from it,” and the Islamophobic reproduction of the Muslim woman and man subject achieves that very aim.[107] While violence and terror are the principal makers of Muslim masculinity, the veil and its accompanying dialectic of subordination make it the feminine analog.

This gendered dialectic generates the unique modalities in which Muslim men and Muslim women are imagined, are politically understood, and experience the law. While lands, borders, and physical spaces in between are the sites of masculine Muslim policing and violence, the female body is the battleground for feminine Islamophobia. Veiling is the most lucid vestige of masculine Muslim tyranny and terror imposed on the Muslim woman and, as explained above, the vehicle that the opportunistic Islamophobe operates to justify violence. The prominence of the veil signifies the reign of terror in the minds of the Islamophobe, while its absence or en masse removal, spurred by the war, represents winning hearts and minds.[108] Unveiling, through the colonial and modern courses of aggression in Muslim-majority cases, is as violent as any act of war.

Like the Orientalist, the Islamophobe fails to recognize a cardinal reality: not all Muslim women veil. Even more, not all Muslim women express their religious identity through the veil’s myriad iterations. This is particularly true in Muslim-majority countries, such as Turkey and Tunisia, and in western nations, like the United States and France, where the War on Terror drives policy. Through a gendered Islamophobic discourse, Muslim women who do not cover are viewed as liberated or independent, western, and assimilable. These views are complicated, if not undermined, by a gendered Islamophobia inextricably constructing Muslim women through their relation to veiling.

The veil, however, is not merely a marker of subordination and other normative judgments. It is also a signifier of connectivity to Islam, Muslim societies, and Muslim men: the imagined purveyors of terrorism. Unveiling represents emancipation from the Muslim man and his dominion, which, in line with virtues of assimilability and modernity, makes the Muslim woman palatable to the Islamophobe. In some respects, as she succeeds in distancing herself from the Muslim male, the tyrant and terrorist in the minds of the Islamophobe, she becomes an asset. She can only be trusted if she unveils, and in doing so, becomes exempt from the class of Muslim women signifying a threat. In mutating her appearance according to western norms, the unveiled Muslim woman becomes a useful expedient to the broader campaign of antiterrorism against Muslim men.[109]

Despite being subordinated and disempowered, the veiled Muslim woman may still serve as a collateral terror threat. As the Islamophobe characterizes her as needing saving to justify war, the fear of the veiled Muslim woman as an accessory to terrorism by the Muslim male remains a looming concern. [110] This woman, despite her suppression, comforts the male terrorist, harbors him, and, if he compels her to do so, tacitly partakes in the enterprise of terrorism. The very presence of the veil therefore ties Muslim women to Muslim men, to their Islam, and to their looming threat of terror.

The Islamophobic dogma tied to the veil strips Muslim women of agency and, vis-à-vis the article of clothing, forecloses the expanse of Muslim feminine individuality and the endless expanse of feminine expression. Many are worth mentioning.

“[T]he headscarf has no unitary meaning.”[111] In response to rising Islamophobia in France and the United States, many Muslim women who previously did not veil did so as an act of political resistance. For some, either spirituality or politics, or a combination of both, spurred this pivot.[112] In the case of Algerian women fighting for independence against the French, the hijab and the niqab were converted into instruments for liberation, through which armed revolutionaries safely passed military checkpoints under their anonymizing shields.[113] For others, donning the hijab is an expression of rejecting western “normative standards of femininity” in exchange for subaltern alternatives.[114]

As Mernissi notes, “[v]eiling is a political statement.”[115] Its origins, however, are not. Hijab itself, as a form of women’s covering, is a practice found across Abrahamic faiths. For Muslim women, wearing hijab is rooted in the Quran’s details on how Muslim women and men should cover. The politicization of hijab is an effect of imperialism, and its generative nomos isolates the article as a marker of mystery, mastery, dependence, and difference.

Muslim women who do not veil, again in line with gendered Islamophobe tropes, are perceived as less pious, secular, or even non-Muslim. Yet, the lived realities of Muslim women powerfully belie these myths. Correlating piety with veiling, or abstaining from it, veers from the truths of spiritual Muslims who see faith as a metaphysics, not material garments. Anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod, a scholar of gender and Islamic societies, observes how “[Muslim] women’s embrace of the hijab” may also be a “public assertion of morality,” divorced from (religious) piety and in line with personal sensibilities.[116] To bring this dynamism of the veil to the fore and to dislodge it from a unitary narrative of dependence and subordination requires a gendered Islamophobic analysis.

More than theoretical discourse, this Islamophobic fixation on veiling and unveiling is a focal matter of law. It shapes the legal movements to restrict myriad forms of covering within the public spheres in places like Quebec and France, sites of Hijab Ban legislation.[117] It drives the normative judgments assigned to Muslim women who express their outward identities beyond the rigid tropes reproduced by Islamophobic propaganda and policy. Donning a symbol indelibly connected to the Orient and disconnected from the West, it brands Muslim women as forever foreign, eternal immigrants, and utterly inassimilable.[118] And thus, as examined in Part III(A), it sits at the very heart of phantasmic culture wars that situate Muslim women at their core, while prevailing theory sweeps them to the margins.

Before transitioning from theory to the empirical and legal analyses in Parts II and III, Crenshaw’s imperative to craft theory “demarginalizing” Black women is apropos for our proposed theory. Adhering to the movement she pioneered more than three decades ago, this Article likewise demarginalizes Muslim women and their lived realities. Adapting Crenshaw’s call,

“[We] center [Muslim] women in this analysis in order to contrast the multidimensionality of [Muslim] women’s experience with the single-axis [bound to veiling] that distorts these experiences . . . [T]his juxtaposition reveal[s] how [Muslim] women are theoretically erased.”[119]

Let us be clear, a gendered Islamophobia theory seeks to do more than just demystify the longstanding tropes that veil scholarly acknowledgement of the rich and multidimensional forms of Muslim womanhood, and collaterally, Muslim men. This Article’s goals are far grander and aim to equip scholars and advocates with the tools to fight back within the gates of societal, intellectual, and state power.

II. Measuring Gendered Islamophobia

The public’s imagining of Muslim womanhood, in juxtaposition to Muslim manhood, is central to gendered Islamophobia theory. Public opinion remains a critical component of private Islamophobia and public conceptualizations of women dictate how the law treats them.[120] In order to understand how the public’s perceptions reify gendered Islamophobia and manifest the dialectic with state action, this Part offers original empirical evidence to the legal literature.

The original empirical evidence is drawn from a survey conducted on a multi-racial sample of Americans from across the United States. This survey provides a unique investigation of the gendered dynamics in the public’s imagery of Muslims. Examining public opinion provides additional understanding of the private manifestations of Islamophobia and specifically how Muslim women are viewed via distinct stereotypes compared to men. This provides meaningful evidence demonstrating how Islamophobic tropes are intrinsically gendered.

The survey findings showcase the gendered dimensions of private Islamophobia as an integral part of maintaining notions of gendered Islamophobia at large. This Part first explains the methodology, moves into the process of creating and deploying our survey instrument, and then discusses key findings from the analysis. The survey results highlight the specific racialized attributes attached to Muslims, particularly how Muslim women are consistently seen as submissive and Muslim men are viewed as dominant and violent.[121] The public’s support of specific policies underscores the sociopolitical consequences of holding stereotypical views of Muslims and how potent normative judgments of Muslims are, as Part III’s examination of case law articulates. Finally, the system of structural racism that is endemic within the United States influences the types of beliefs individuals hold, such as White respondents being more likely to treat Muslims with greater suspicion in comparison to non-Whites.[122]

A. Survey Methodology

To measure the dynamics of gendered Islamophobia, we collected original survey data on 1,230 Americans aged 18 and older during November and December of 2021 using an online panel survey.[123] The value of our original data collection is that it provides a timely and contemporary understanding of how Islamophobia exists.

Our survey included originally designed questions focused on the gendered dynamics of Islamophobia. Furthermore, our analysis assessed opinions about Muslim men and Muslim women to determine whether opinions on stereotypes or policies shift if, within the survey experiments, we specify the subject’s gender in addition to their Muslim identity. Prior surveys have typically focused on the public’s opinion of Muslims at large, whereas our survey provided more granular questions. Such questions helped uncover differences in opinions and perceptions of Muslim women versus Muslim men. These findings illuminate how Muslim women are publicly imagined and understood and how they are perceived in relation to Muslim men.

Our survey also engaged with widely cited data on Muslim Americans. It integrated questions that draw on additional attitudes, such as political participation questions from the American National Election Study of 2020 and Nazita Lajevardi’s Muslim American resentment scale, a ten-question survey scale that measures Americans’ general animus towards Muslims.[124]

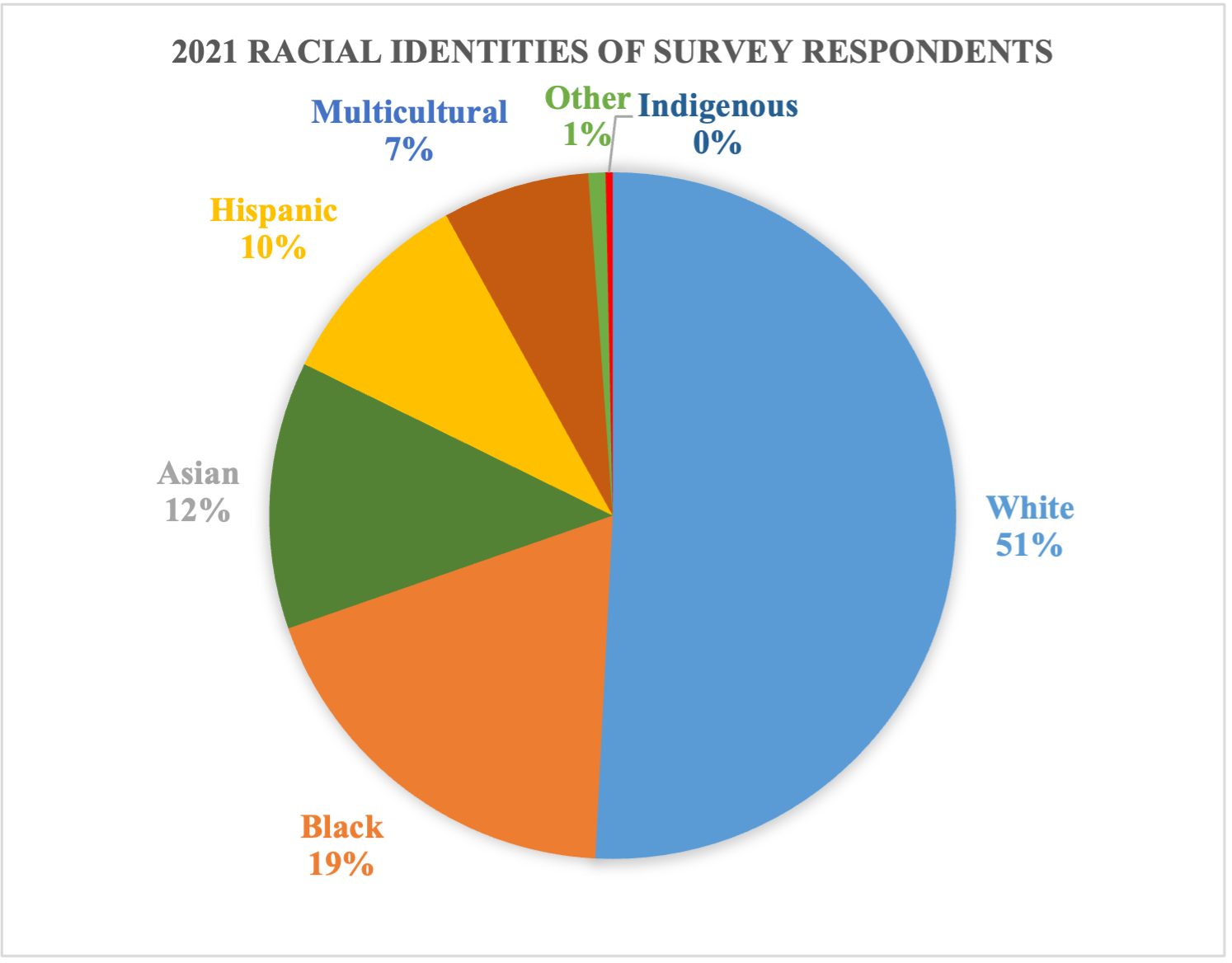

Figure 3 highlights the distribution of respondents by racial background in the analysis. Fifty-one percent of respondents identify as White, 19% as Black, 12% as Asian, and 10% as Hispanic. The racial diversity within the sample helps us understand what divergences there are in the understanding of Muslims by racial background, if any. The racial diversity of the respondent sample is important as attitudes towards minority groups in the United States typically vary by racial background and we may see a similar racial divide in perceptions towards Muslims.[125]

Figure 3 | Racial Background of Respondents in 2021 Survey

B. General Public Favorability

Our framing of gendered Islamophobia orients Muslim women as the simultaneous subjects of imperial saving while Muslim male violence deepens and complicates prevailing understandings of Muslim Americans. As Figure 4 illustrates, Muslim women—on average—are perceived in a more favorable light than Muslim men. Respondents were given a “feeling thermometer,” whereby they were asked about their general feelings towards certain communities in the United States. A rating of 5 or higher out of 10 indicated they felt favorable and warm towards the individual. Ratings below 5 indicated they did not feel favorable towards the individual. Our survey asked them about 4 groups of persons: Religious People (as the control group), Muslim Women with No Hijab, Muslim Women with Hijab, and Muslim Men. As Figure 4 highlights, Muslim men were the least liked in the group and the only one that, on average, received a thermometer score of less than 5: 4.9. The rest of the groups scored a rating of 5 or higher, including Muslim Women with or without Hijab. The variation in the impression between Muslim women and Muslim men highlights how they are perceived distinctively.

As gendered Islamophobia theory emphasizes, individuals with Islamophobic tendencies perceive Muslim females who are veiled in negative ways. Our findings corroborate this perspective. For the American public, favorability varies between Muslim women who wear the hijab and those who do not. Muslim women who do not wear hijab were perceived as more favorable than those who do wear hijab. Muslim women with hijab were given an average favorability score of 5.92 out of 10, whereas Muslim women without hijab were given a higher score of 6.31. Even among Muslim women, there are differences in how they are perceived based on their appearance and proximity to Islam (vis-à-vis the hijab). This distinction is important, as it reveals that the public may welcome certain kinds of Muslim women more than others.

Figure 4 | Favorability Thermometer in 2021 Survey

C. The Gendered “Racing” of Muslims

Specific stereotypes that are consistently used to describe Muslim women in juxtaposition to Muslim men are dominant factors in reifying gender Islamophobia. This relational dialectic, where Muslim womanhood is shaped against the construction of Muslim masculinity, is important to measure. Muslim men’s violent characterization engenders the Islamophobic notion of Muslim women being submissive. By placing men as the active agent in the narrative, women are cast as meek and passive actors. We measured these two stereotypes, violent and submissive, as distinctive questions to understand whether respondents do note any variation in the stereotype or whether they paint Muslim men and women with the same stereotypical brush.

1. Muslim Men as “Violent”

Since Muslim women’s agency is constantly compared to men’s agency, we first examined associations with the stereotype of being violent. The first question asked individuals to place groups of people onto a scale from 0 to 100. The 0 side of the scale included the attribute of “peaceful,” while the 100 side of the scale was designated for “violent.” If respondents selected 50% for a group, this indicated general ambivalence. This scale offers a contrast between peaceful and violent sentiments and asks respondents to gauge where subgroups of people fall on the scale. We specifically asked about Muslim men and Muslim women, and Asian Americans and Black Americans as comparison groups.[126] Responses were analyzed based on the respondent’s racial identity.

Figure 5 illustrates a gendered and racialized perception of violence that neatly maps into the subgroups assessed. On average and across all racial groups of respondents, Muslim women and Asian Americans were seen as most peaceful. This is telling as it highlights how, in the public imagery, Muslim women do not convey the same “violent tendencies” as their male counterparts. Conversely, Muslim men and Black Americans were perceived to be more violent than peaceful. This is consistent with results when looking at the general population’s average and even when responses are split and examined by racial subgroups. There is a drastic decline in perceptions of violence when we move away from the example of Black Americans and Muslim men. The conceptualization of the pervasive stereotype that Black men are violent has been as endemic in the racialization of Black Americans as it has been for Muslim men.[127] On the other hand, Asian Americans have been placed in a role as a “model minority," which depicts them as smarter and more likely to be orderly.[128]

Importantly, the difference in Muslim women being perceived as less violent reifies how Muslim women are perceived distinctly from Muslim men.

Figure 5 | Perceptions of Violence by Group Identity in 2021 Survey

The respondents’ written comments provide further insight into these findings. The final survey question is open-ended, allowing respondents to write whatever comes to mind when they think of Muslim men and Muslim women, distinctly. One respondent shared,

I grew up in California near San Bernardino. I now live in Texas. But, I have extended family in [California]. A few years ago when the terrorist attack happened in San Bernardino, I had cousins living and working in Loma Linda and San Bernardino right around where the attack happened. One cousin worked for the county but in a different department than the male terrorist. I was glued to my phone texting people to make sure they were safe. Now, even though I know that most Muslims are not violent or dangerous, I can’t stop myself from having a little suspicion until I know a specific individual is a good person.

The suspicion with which this respondent approached Muslim men offers a more intimate picture of what events or ideas produce these perceptions in their minds. This respondent specifically referenced the San Bernardino case when asked about stereotypes associated with Muslim men.[129] This allusion was not referenced in other open-ended answers related to Muslim women.

This anecdote is consistent with descriptors regarding how Muslim men were commonly perceived. What is meaningful in this respondent’s answer is their confession that, “they cannot stop themselves from having a little suspicion” about the violent tendency of Muslim men. This signifies how, for this respondent, Muslims are guilty until they are presumed innocent; a form of heightened alarm is activated when the subjects of scrutiny are Muslim men.

2. Muslim Women as “Submissive”

If Muslim men are violent, where does that leave Muslim women in the public’s imagery? The second side of this notion of gendered Islamophobia is how Muslim womanhood is shaped to configure Muslim women as submissive. The second question asked respondents, on the stereotype scale, to measure the degree of outspokenness or submissiveness of the five subgroups featured in Figure 6: Politicians, Black Americans, Muslim Men, Asian Americans, and Muslim Women.

As Figure 6 highlights, Muslim women are perceived to be the most submissive, followed by Asian Americans. Among the five subgroups, Muslim women were graded an average of 62.33% more likely to be submissive than outspoken. They are seen as the most likely to be submissive, even when compared to other groups beyond Muslim men. On the opposite side of the spectrum, respondents were asked about politicians as a control group. They were graded as having a 22.9% chance of being submissive. With an average of 41.75%, Muslim men were seen as drastically less submissive and more outspoken than Muslim women with an average of 62.33%. The entrenchment of these associations in the public mind are stark. These linkages not only demonstrate how distinctive the stereotypes associated with Muslim women are but also highlight how passive and submissive Muslim women are perceived to be.

Figure 6 | Perceptions of Submissiveness by Group Identity in 2021 Survey

The respondents’ written comments provided color to the findings. In the open-ended section of the survey, one respondent shared that Muslim women were, “Submissive, quiet, scared, shy . . . Submissive to male family members . . . submissive to their fathers and husbands.” Another respondent noted more directly, “I think of women who run the home and are often stay-at-home moms who are servants to their husband, though I hope this is changing.” Over 120 out of 1,230 respondents utilized the term “submissive” directly in their open commentary about Muslim women. “Submissive,” “passive,” and similar gendered adjectives were pervasive across the open-ended commentary.

Conversely, respondents did not use any blanket term as a heuristic when asked about Muslim men. In some ways, this not only highlights how pervasive this stereotype of Muslim women is, but also how simplistic people’s notions of Muslim women are. Muslim men are painted in more complex terms, whereas the characterization of Muslim women was monolithic and flattened.

D. Policy Implications

These findings align with the theory articulated in Part I and illustrate deeply gendered public perceptions of Muslims. These perceptions have indelible policy and legal implications. The implications of the differences in opinions by racial groups is particularly meaningful when examining support for policies. We found there is variation on who is more hesitant at the reception of new immigrants, varying by the respondent’s racial background.

1. Support for Immigration in the United States

Former President Donald Trump’s “Muslim ban” introduced extreme immigration measures targeting Muslim majority countries. Immigration remains a salient component of discourse surrounding Muslims in the United States. Respondents were asked whether to increase, decrease, or maintain the level of immigration in the United States.[130] Figure 7 highlights how people’s views on immigration levels vary by their ethno-racial background. Results are broken down by the ethno-racial background of survey respondents. Support for decreasing immigration varied by respondents’ ethno-racial background. Whites constituted the group with the highest desire to decrease immigration, with 34.4% wanting to decrease immigration levels. On the other hand, only 17.7% of Black respondents chose to decrease immigration levels. Conversely, other ethno-racial groups were more supportive of increasing immigration levels. 35.78% of Black Americans wanted to increase immigration. South Asians constituted the group most supportive of increasing immigration, as 45.45% of respondents wanted to increase immigration levels. On the other hand, only 21.88% of East Asian respondents chose to increase immigration levels.

Figure 7 | Support for Changing Immigration Levels in 2021 Survey

Moving beyond general support for immigration policy, we asked respondents specifically about their views on hypothetical immigration asylum cases. The survey measured support for asylum by focusing on the country of origin of the immigrant in question. Respondents were asked about three immigrants: (1) Patrick from Ireland; (2) Fatima, a Muslim woman from Afghanistan; (3) Ahmad, a Muslim man from Afghanistan.

White respondents were more favorable toward admitting an Irish immigrant than admitting a Muslim one, regardless of gender.[131] This variation in support was not found among non-Whites; it existed only among White respondents. The evidence here indicates that for White Americans, the racial and religious identity of the immigrant is most salient in influencing their decision to support the immigrant’s entry into the country.

A linear regression analysis of the question further unpacked this finding. The regression analysis helps control for additional factors beyond race. We found that even when controlling for education, class, age, and ideology, White respondents were more supportive than non-Whites of Irish immigrants, the difference being statistically significant.[132]

Figure 8 | Support for Asylum by White Respondents in 2021 Survey

2. Support for Hijab Ban Policy

As Figure 4 previously illustrated, Muslim women with hijab were perceived less favorably than Muslim women without hijab. Extending on this question, respondents were asked about whether women who wore hijab would have trouble assimilating in the United States. Concern over the hijab was robust among the respondents. As shown in Figure 9, individuals were asked whether they believed that Muslim women who do wear a hijab will face a challenge integrating into American society; a staggering 57% agreed that they would.[133]

Figure 9 | Perceptions of Muslim Women Wearing Hijab in 2021 Survey

Interestingly, while concerns emanate over hijab, there is less support to completely ban hijab from public life. Figure 10 highlights the general disagreement with the statement, “wearing headscarves should be banned in all public places,” which distinguishes American sentiment regarding hijab bans from France and Quebec.[134] The x-axis highlights the percentage of support for each answer category. The highest levels of support to keep hijab in public came from South Asian and Black respondents, with 77.27% and 68.97% respectively, and decrease by sub-group thereafter.

Finally, in a linear regression trying to predict support, we found that rather than racial background, ideology informs the likelihood to support a hijab ban. Ideologically conservative respondents were more likely to support a hijab ban than others and, again, this difference is statistically significant.[135]

Figure 10 | Support for Women to Wear Hijab in Public Places, by Percentage

The empirical findings described here provide a detailed account of how perceptions of Muslims vary by gender. Muslim women are overwhelmingly perceived as submissive, quiet actors that cower to the will of Muslim men. The variation of favorability is distinctive between Muslim women, whereby Muslim women with hijab are perceived less favorably than women who do not wear hijab. This result is consistent with how narratives within gendered Islamophobia discourse are crafted.

The policy implications for these perceptions are also meaningful. For White Americans, the type of immigrant in question matters when supporting their asylum. They are more favorable to permitting non-Muslim immigrants than immigrants from Afghanistan. Muslim immigrants, particularly men, remain closely associated with inassimilability, at best, and terrorism, at worst. This illustrates that Islam remains deeply racialized in the minds of respondents, particularly White respondents, and when paired with gender determines who is—and is not—a direct security threat. The policy implications of public opinion provide vital nuance as we deliberate the structural implications of the American public’s imagining of Muslims, and the project of unveiling the law of gendered Islamophobia.

III. The Law of Gendered Islamophobia

Case law involving Muslim women offers a third portal of insight into the gendered dimensions of Islamophobia. While Part I framed the theory of gendered Islamophobia and Part II introduces new empirical evidence into the literature, this Part of the Article analyzes leading cases implicating Muslim womanhood, and consequently, reveals how Islamophobia manifests distinctly along gendered lines. These cases, and this Part’s reframing of them, unveils the “dominant” legal narratives about Muslims, and specifically Muslim women, authored by predominantly male White judges in the areas of (1) hijabs bans; (2) counterterrorism prosecution; and (3) immigration and asylum adjudication.

A. Hijab Bans

The policing of Muslim women’s bodies, by way of legislation and other forms of state action, is the starkest manifestation of feminine Islamophobia. While prevailing Islamophobia discourse fixates on terrorism (or the threat of it) as the quintessential locus of legislative and judicial regulation, a gendered lens reveals this is not the case for Muslim women.

This Section analyzes two leading hijab ban cases: (1) the Hijab Ban in Quebec, Canada, enacted by the provincial National Assembly on June 16, 2019; and (2) a “situational Hijab Ban” enforced by the Philadelphia Police Department against a Black Muslim female police officer, Kimberlie Webb.[136] Together, these cases illustrate a gendered Islamophobic motive to regulate the bodies of Muslim women beyond the immediate scope of terrorism and counterterrorism.

1. Lies, Laïcité, and the Law: Quebec’s Hijab Ban

The French “Hijab Ban” stands as the structural harbinger of feminine Islamophobia.[137] The measure, enacted in 2004, was once viewed as a distinct spawn of the French commitment to laïcité—a debated principle enshrined today as secularism.[138] Scholars have argued that laïcité is the “equivalent of a religion” and effectively serves as the de facto faith of the modern French state.[139]

Fifteen years later, in June of 2019, Quebec enacted a copycat measure. In doing so, the province divested from the Canadian mandate of “multiculturalism” in favor of modern French policy.[140] Quebec’s provincial legislature adopted the mandate of policing Muslim women’s bodies through its own hijab ban, steered by the very gendered discourse espoused in France, its past colonial master and modern muse.[141]

Like its French predecessor, Bill 21 is designed to police Muslim life through direct regulation of Muslim women’s bodies. Titled “An Act Respecting the Laicity of the State,” the measure mandates (1) the separation of State and religions; (2) the religious neutrality of the State; (3) the equality of all citizens; and (4) freedom of conscience and freedom of religion.”[142] The first two structural prongs form the state enshrinement of secularism, which, when enforced, disproportionately targets members of faith groups who express their faith through “wearing religious symbols,” such as the Jewish yarmulke, Sikh turban, or hijab.[143] The guarantees of the third and fourth prongs—equality and freedom of conscience and religion respectively—are materially eroded for Muslim women in public spaces such as government, courts, and schools.[144] Bill 21 erodes the religious freedom of women and targets the veil as the principal symbol of cultural difference within Quebec.

More than just legislation, Bill 21 is an expression of popular Islamophobia in the province. Introduced by the Coalition Avenir Quebec (CAQ), the nativist party that pushes anti-Muslim rhetoric as part of its political platform, Bill 21 passed with a vote of 73–35 in June of 2019.[145] Legislators with the CAQ-controlled provincial government testified that Muslim men imposed the hijab on their wives and daughters and that the hijab stood as an affront to the Quebecois tradition of separation between religion and state.[146]

The legislative history of the bill makes its Islamophobic purpose clear. During the public hearings, Senator Hervieux-Payette made links “between the veil, excision, genital mutilation, [and] forced marriage.”[147] Christiane Pelchat, an advocate of Bill 21, stated that it was “difficult to reconcile the wearing of the Islamic headscarf with the message of tolerance, respect for others, and above all gender equality.”[148] Despite its facially neutral design, the gendered dynamic of Muslim male dominance stripping Muslim women of existential self-determination saturated the intent of its framers as well as the popular and political rhetoric driving it.[149]

The public’s support for Bill 21 unveils another dimension of how gendered Islamophobia plays out in the law. Legislators championing the measure, amid the controversy that arose in its wake, defended it on grounds of “popular support” among Quebec’s constituents.[150] While only 41% of Canadians outside of Quebec support Bill 21, a 2019 Forum Research Survey showed it maintained a strong majority of support (64%) in the province.[151] This private expression of feminine Islamophobia fused with the legislative will to enshrine it manifests how dialectical Islamophobia is more pronounced in Quebec versus the remainder of Canada, who oppose the Bill—and what it represents—at a far higher clip.[152] As Canadian culture scholar Peter Behrens notes,

Islamophobic hysteria in France has been appropriated by some Quebecois who are by no means backwoodsmen, but friends of a global Francophonie and educated apologists for all things French: the same people who teach, write, run for office—and pass laws like Bill 21.[153]

Quebec’s legal and normative divergence from the remainder of the country is buoyed by its ties to French culture and legally, its distinct color of nativism, racism, and religious animus. Anything but neutral when the targets are Muslims, laïcité—in its prototypical French and Quebecois forms—arms the state with the legal basis to strip Muslim women of the very self-determination it charges Muslim men of seizing.

Bill 21, like its predecessor, aims to step between oppressive Muslim men imposing the hijab and Muslim women.[154] By purporting to liberate women, its fundamental purpose is to retrench the spread of Muslim life and culture by policing Muslim women within public spaces. In short, the law polices the spread of Islam in Quebec through the regulation of the Muslim female body and punishes those who resist the mandate of unveiling in the public sphere.

Cases like that of Fatameh Anvari, a third-grade teacher in Chelsea, Quebec, who was “banned from teaching because she wears a hijab” proliferated after Bill 21’s enactment.[155] The legislation imposed an ultimatum on Muslim women like Anvari to choose between their career and faith, eliminating “equality” and “freedom of religion” for Muslim women like Anvari.[156] Yet, Muslim male teachers or elected male officials, lawyers and public administrators, and members of the majority Christian traditions in Quebec did not face this experience nor the undue hardship it sowed. Enforcement of Bill 21 disproportionately fixated on Muslim women donning the hijab in public spaces. Students, colleagues, and strategically planted informants in government buildings, courthouses, and most prominently, Quebec’s public schools, became the “secularism police” to execute the Bill’s fixation. [157]

Thus, the named plaintiff challenging Bill 21 in court being a Muslim woman who wears the hijab came as no surprise. Ichrak Norel Hak, an undergraduate at the University of Montreal preparing for a career in teaching, sued the province on grounds that “[Bill 21] is forcing her to choose between [her] dream and the preservation of [her] identity.”[158] Moroccan by origin and having lived in Montreal since 1994, Hak sees teaching as a calling. She says her plans to teach French to newly arrived immigrants are thwarted by the fact that as a practicing Muslim who wears the hijab out of personal choice, she will not be able to teach without having to remove her veil. This not only shocks and hurts her, but also injures her due process, free exercise of religion, and dignity.[159] Hak stood as a poignant archetype for the class of Muslim women unduly burdened by the ban.

The petitioners in Hak noted how the Bill weaponized “religious neutrality” to coerce Muslim women to conform, compromise, and surrender their religious freedom.[160] Through powerful testimony, Hak affirmed how the decision to wear the hijab is “her personal choice,” challenging the gendered Islamophobia underlying Bill 21 that the article is imposed upon Muslim women by the men in their lives.[161] Further, as law scholar Marsi Matsuda notes that “speech also positions people socially,” Hak’s accent-free French speech and strident independence shattered Bill 21’s feminine Islamophobic tropes.[162]