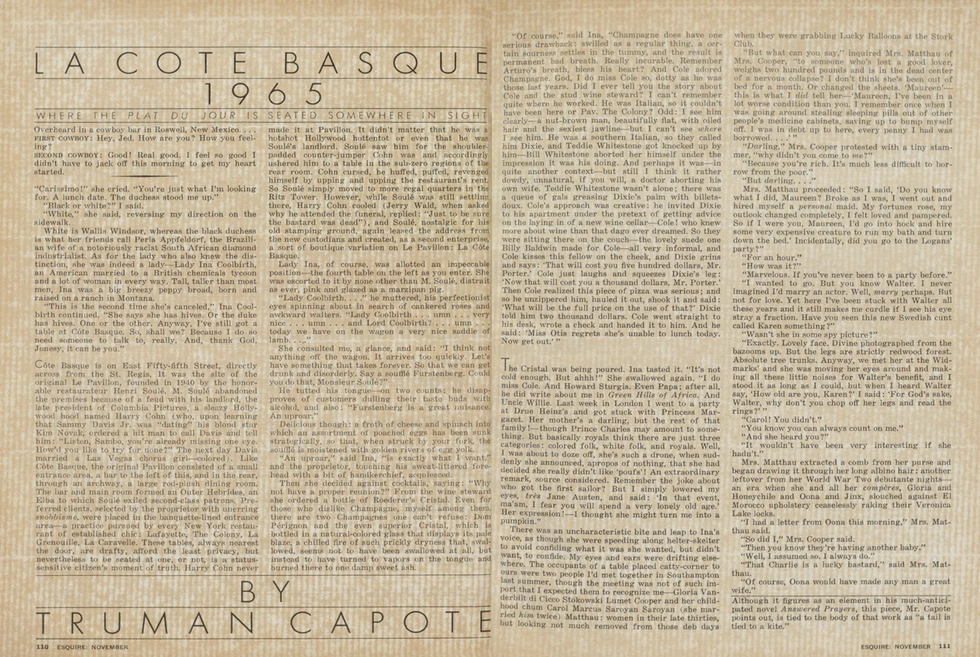

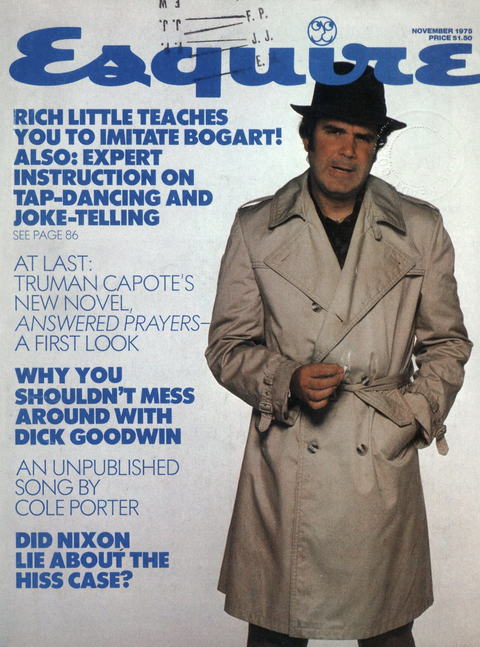

Truman Capote's "La Côte Basque," originally published in the November 1975 issue of Esquire, was meant to serve as the first taste from his upcoming masterpiece about the inner circles of high society women. That novel, eventually called Answered Prayers, wouldn't publish until after the writer's death, but the passage became famous for the scandals it brought. In 2024, it was adapted for the television screen, for FX's Feud: Capote vs. the Swans. Available in full, below, it contains insensitive descriptions of beauty and body standards. To read every story ever published in Esquire, upgrade to All Access.

Overheard in a cowboy bar in Roswell, New Mexico....

FIRST COWBOY: Hey, Jed. How are you? How you feeling?

SECOND COWBOY: Good! Real good. I feel so good I didn’t have to jack off this morning to get my heart started.

“Carissimo!” she cried. “You’re just what I’m looking for. A lunch date. The duchess stood me up.”

“Black or white?” I said.

“White,” she said, reversing my direction on the sidewalk.

White is Wallis Windsor, whereas the black duchess is what her friends call Perla Appfeldorf, the Brazilian wife of a notoriously racist South African diamond industrialist. As for the lady who also knew the distinction, she was indeed a lady—Lady Ina Coolbirth, an American married to a British chemicals tycoon and a lot of woman in every way. Tall, taller than most men, Ina was a big breezy peppy broad, born and raised on a ranch in Montana.

“This is the second time she’s canceled,” Ina Coolbirth continued. “She says she has hives. Or the duke has hives. One or the other. Anyway, I’ve still got a table at Côte Basque. So, shall we? Because I do so need someone to talk to, really. And, thank God, Jonesy, it can be you.”

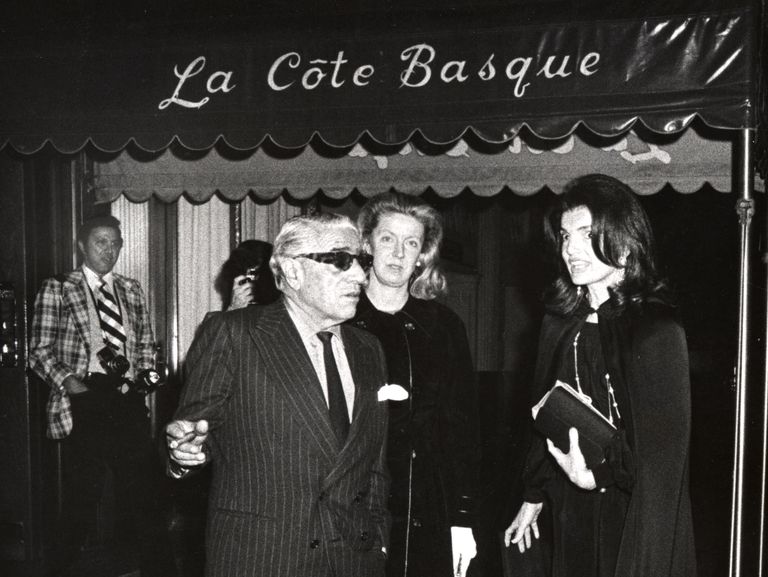

Côte Basque is on East Fifty-fifth Street, directly across from the St. Regis. It was the site of the original Le Pavilion, founded in 1940 by the honorable restaurateur Henri Soulé. M. Soulé abandoned the premises because of a feud with his landlord, the late president of Columbia Pictures, a sleazy Hollywood hood named Harry Cohn (who, upon learning that Sammy Davis Jr. was “dating” his blond star Kim Novak, ordered a hit man to call Davis and tell him: “Listen, Sambo, you’re already missing one eye. How’d you like to try for none?” The next day Davis married a Las Vegas chorus girl—colored). Like Côte Basque, the original Pavilion consisted of a small entrance area, a bar to the left of this, and in the rear, through an archway, a large red-plush dining room. The bar and main room formed an Outer Hebrides, an Elba to which Soulé exiled second-class patrons. Preferred clients, selected by the proprietor with unerring snobbisme, were placed in the banquette-lined entrance area—a practice pursued by every New York restaurant of established chic: Lafayette, The Colony, La Grenouille, La Caravelle. These tables, always nearest the door, are drafty, afford the least privacy, but nevertheless to be seated at one, or not, is a status-sensitive citizen’s moment of truth. Harry Cohn never made it at Pavilion. It didn’t matter that he was a hotshot Hollywood hottentot or even that he was Soulé’s landlord. Soulé saw him for the shoulder-padded counter-jumper Cohn was and accordingly ushered him to a table in the sub-zero regions of the rear room. Cohn cursed, he huffed, puffed, revenged himself by upping and upping the restaurant’s rent. So Soulé simply moved to more regal quarters in the Ritz Tower. However, while Soulé was still settling there, Harry Cohn cooled (Jerry Wald, when asked why he attended the funeral, replied: “Just to be sure the bastard was dead”), and Soulé, nostalgic for his old stamping ground, again leased the address from the new custodians and created, as a second enterprise, a sort of boutique variation on Le Pavilion: La Côte Basque.

Lady Ina, of course, was allotted an impeccable position—the fourth table on the left as you enter. She was escorted to it by none other than M. Soulé, distrait as ever, pink and glazed as a marzipan pig.

“Lady Coolbirth….” he muttered, his perfectionist eyes spinning about in search of cankered roses and awkward waiters. “Lady Coolbirth … umn … very nice … umn … and Lord Coolbirth? … umn … today we have on the wagon a very nice saddle of lamb….”

She consulted me, a glance, and said: “I think not anything off the wagon. It arrives too quickly. Let’s have something that takes forever. So that we can get drunk and disorderly. Say a soufflé Furstenberg. Could you do that, Monsieur Soulé?”

He tutted his tongue—on two counts: he disapproves of customers dulling their taste buds with alcohol, and also: “Furstenberg is a great nuisance. An uproar.”

Delicious though: a froth of cheese and spinach into which an assortment of poached eggs has been sunk strategically, so that, when struck by your fork, the soufflé is moistened with golden rivers of egg yolk.

“An uproar,” said Ina, “is exactly what I want,” and the proprietor, touching his sweat-littered forehead with a bit of handkerchief, acquiesced.

Then she decided against cocktails, saying: “Why not have a proper reunion?” From the wine steward she ordered a bottle of Roederer’s Cristal. Even for those who dislike Champagne, myself among them, there are two Champagnes one can’t refuse: Dom Pérignon and the even superior Cristal, which is bottled in a natural-colored glass that displays its pale blaze, a chilled fire of such prickly dryness that, swallowed, seems not to have been swallowed at all, but instead to have turned to vapors on the tongue and burned there to one damp sweet ash.

“Of course,” said Ina, “Champagne does have one serious drawback: swilled as a regular thing, a certain sourness settles in the tummy, and the result is permanent bad breath. Really incurable. Remember Arturo’s breath, bless his heart? And Cole adored Champagne. God, I do miss Cole so, dotty as he was those last years. Did I ever tell you the story about Cole and the stud wine steward? I can’t remember quite where he worked. He was Italian, so it couldn’t have been here or Pav. The Colony? Odd: I see him clearly—a nut-brown man, beautifully flat, with oiled hair and the sexiest jawline—but I can’t see where I see him. He was a southern Italian, so they called him Dixie, and Teddie Whitestone got knocked up by him—Bill Whitestone aborted her himself under the impression it was his doing. And perhaps it was—in quite another context—but still I think it rather dowdy, unnatural, if you will, a doctor aborting his own wife. Teddie Whitestone wasn’t alone; there was a queue of gals greasing Dixie’s palm with billets-doux. Cole’s approach was creative: he invited Dixie to his apartment under the pretext of getting advice on the laying in of a new wine cellar—Cole! who knew more about wine than that dago ever dreamed. So they were sitting there on the couch—the lovely suede one Billy Baldwin made for Cole—all very informal, and Cole kisses this fellow on the cheek, and Dixie grins and says: ‘That will cost you five hundred dollars, Mr. Porter.’ Cole just laughs and squeezes Dixie’s leg: ‘Now that will cost you a thousand dollars, Mr. Porter.’ Then Cole realized this piece of pizza was serious; and so he unzippered him, hauled it out, shook it and said: ‘What will be the full price on the use of that?’ Dixie told him two thousand dollars. Cole went straight to his desk, wrote a check and handed it to him. And he said: ‘Miss Otis regrets she’s unable to lunch today. Now get out.’”

The Cristal was being poured. Ina tasted it. “It’s not cold enough. But ahhh!” She swallowed again. “I do miss Cole. And Howard Sturgis. Even Papa; after all, he did write about me in Green Hills of Africa. And Uncle Willie. Last week in London I went to a party at Drue Heinz’s and got stuck with Princess Margaret. Her mother’s a darling, but the rest of that family!—though Prince Charles may amount to something. But basically royals think there are just three categories: colored folk, white folk, and royals. Well, I was about to doze off, she’s such a drone, when suddenly she announced, apropos of nothing, that she had decided she really didn’t like ‘poufs’! An extraordinary remark, source considered. Remember the joke about who got the first sailor? But I simply lowered my eyes, très Jane Austen, and said: ‘In that event, ma’am, I fear you will spend a very lonely old age.’ Her expression!—I thought she might turn me into a pumpkin.”

There was an uncharacteristic bite and leap to Ina’s voice, as though she were speeding along helter-skelter to avoid confiding what it was she wanted, but didn’t want, to confide. My eyes and ears were drifting elsewhere. The occupants of a table placed catty-corner to ours were two people I’d met together in Southampton last summer, though the meeting was not of such import that I expected them to recognize me—Gloria Vanderbilt di Cicco Stokowski Lumet Cooper and her childhood chum Carol Marcus Saroyan Saroyan (she married him twice) Matthau: women in their late thirties, but looking not much removed from those deb days when they were grabbing Lucky Balloons at the Stork Club.

“But what can you say,” inquired Mrs. Matthau of Mrs. Cooper, “to someone who’s lost a good lover, weighs two hundred pounds and is in the dead center of a nervous collapse? I don’t think she’s been out of bed for a month. Or changed the sheets. ‘Maureen’—this is what I did tell her—‘Maureen, I’ve been in a lot worse condition than you. I remember once when I was going around stealing sleeping pills out of other people’s medicine cabinets, saving up to bump myself off. I was in debt up to here, every penny I had was borrowed....’”

“Darling,” Mrs. Cooper protested with a tiny stammer, “why didn’t you come to me?”

“Because you’re rich. It’s much less difficult to borrow from the poor.”

“But darling….”

Mrs. Matthau proceeded: “So I said, ‘Do you know what I did, Maureen? Broke as I was, I went out and hired myself a personal maid. My fortunes rose, my outlook changed completely, I felt loved and pampered. So if I were you, Maureen, I’d go into hock and hire some very expensive creature to run my bath and turn down the bed.’ Incidentally, did you go to the Logans’ party?”

“For an hour.”

“How was it?”

“Marvelous. If you’ve never been to a party before.”

“I wanted to go. But you know Walter. I never imagined I’d marry an actor. Well, marry perhaps. But not for love. Yet here I’ve been stuck with Walter all these years and it still makes me curdle if I see his eye stray a fraction. Have you seen this new Swedish cunt called Karen something?”

“Wasn’t she in some spy picture?”

“Exactly. Lovely face. Divine photographed from the bazooms up. But the legs are strictly redwood forest. Absolute tree trunks. Anyway, we met her at the Widmarks’ and she was moving her eyes around and making all these little noises for Walter’s benefit, and I stood it as long as I could, but when I heard Walter say, ‘How old are you, Karen?’ I said: ‘For God’s sake, Walter, why don’t you chop off her legs and read the rings?’”

“Carol! You didn’t.”

“You know you can always count on me.”

“And she heard you?”

“It wouldn’t have been very interesting if she hadn’t.”

Mrs. Matthau extracted a comb from her purse and began drawing it through her long albino hair: another leftover from her World War Two debutante nights—an era when she and all her compères, Gloria and Honeychile and Oona and Jinx, slouched against El Morocco upholstery ceaselessly raking their Veronica Lake locks.

“I had a letter from Oona this morning,” Mrs. Matthau said.

“So did I,” Mrs. Cooper said.

“Then you know they’re having another baby.”

“Well, I assumed so. I always do.”

“That Charlie is a lucky bastard,” said Mrs. Matthau.

“Of course, Oona would have made any man a great wife.”

“Nonsense. With Oona, only geniuses need apply. Before she met Charlie, she wanted to marry Orson Welles … and she wasn’t even seventeen. It was Orson who introduced her to Charlie; he said: ‘I know just the guy for you. He’s rich, he’s a genius, and there’s nothing that he likes more than a dutiful young daughter.’”

Mrs. Cooper was thoughtful. “If Oona hadn’t married Charlie, I don’t suppose I would have married Leopold.”

“And if Oona hadn’t married Charlie, and you hadn’t married Leopold, I wouldn’t have married Bill Saroyan. Twice yet.”

The two women laughed together, their laughter like a naughty but delightfully sung duet. Though they were not physically similar—Mrs. Matthau being blonder than Harlow and as lushly white as a gardenia, while the other had brandy eyes and a dark dimpled brilliance markedly present when her negroid lips flashed smiles—one sensed they were two of a kind: charmingly incompetent adventuresses.

Mrs. Matthau said: “Remember the Salinger thing?”

“Salinger?”

“A Perfect Day for Banana Fish. That Salinger.”

“Franny and Zooey.”

“Umn huh. You don’t remember about him?”

Mrs. Cooper pondered, pouted; no, she didn’t.

“It was while we were still at Brearley,” said Mrs. Matthau. “Before Oona met Orson. She had a mysterious beau, this Jewish boy with a Park Avenue mother, Jerry Salinger. He wanted to be a writer, and he wrote Oona letters ten pages long while he was overseas in the Army. Sort of love-letter essays, very tender, tenderer than God. Which is a bit too tender. Oona used to read them to me, and when she asked what I thought, I said it seemed to me he must be a boy who cries very easily; but what she wanted to know was whether I thought he was brilliant and talented or really just silly, and I said both, he’s both, and years later when I read Catcher in the Rye and realized the author was Oona’s Jerry, I was still inclined to that opinion.”

“I never heard a strange story about Salinger,” Mrs. Cooper confided.

“I’ve never heard anything about him that wasn’t strange. He’s certainly not your normal everyday Jewish boy from Park Avenue.”

“Well, it isn’t really about him, but about a friend of his who went to visit him in New Hampshire. He does live there, doesn’t he? On some very remote farm? Well, it was February and terribly cold. One morning Salinger’s friend was missing. He wasn’t in his bedroom or anywhere around the house. They found him finally, deep in a snowy woods. He was lying in the snow wrapped in a blanket and holding an empty whiskey bottle. He’d killed himself by drinking the whiskey until he’d fallen asleep and frozen to death.”

After a while Mrs. Matthau said: “That is a strange story. It must have been lovely, though—all warm with whiskey, drifting off into the cold starry air. Why did he do it?”

“All I know is what I told you,” Mrs. Cooper said.

An exiting customer, a florid-at-the-edges swarthy balding Charlie sort of fellow, stopped at their table. He fixed on Mrs. Cooper a gaze that was intrigued, amused and ... a trifle grim. He said: “Hello, Gloria”; and she smiled: “Hello, darling”; but her eyelids twitched as she attempted to identify him; and then he said: “Hello, Carol. How are ya, doll?” and she knew who he was all right: “Hello, darling. Still living in Spain?” He nodded; his glance returned to Mrs. Cooper: “Gloria, you’re as beautiful as ever. More beautiful. See ya….” He waved and walked away.

Mrs. Cooper stared after him, scowling.

Eventually Mrs. Matthau said: “You didn’t recognize him, did you?”

“N-n-no.”

“Life. Life. Really, it’s too sad. There was nothing familiar about him at all?”

“Long ago. Something. A dream.”

“It wasn’t a dream.”

“Carol. Stop that. Who is he?”

“Once upon a time you thought very highly of him. You cooked his meals and washed his socks—” Mrs. Cooper’s eyes enlarged, shifted “—and when he was in the Army you followed him from camp to camp, living in dreary furnished rooms—”

“No!”

“Yes!”

“No.”

“Yes, Gloria. Your first husband.”

“That … man … was … Pat di Cicco?”

“Oh, darling. Let’s not brood. After all, you haven’t seen him in almost twenty years. You were only a child. Isn’t that,” said Mrs. Matthau, offering a diversion, “Jackie Kennedy?”

And I heard Lady Ina on the subject, too: “I’m almost blind with these specs, but just coming in there, isn’t that Mrs. Kennedy? And her sister?”

It was; I knew the sister because she had gone to school with Kate McCloud, and when Kate and I were on Abner Dustin’s yacht at the Feria in Seville she had lunched with us, then afterward we’d gone water-skiing together, and I’ve often thought of it, how perfect she was, a gleaming gold-brown girl in a white bathing suit, her white skis hissing smoothly, her brown-gold hair whipping as she swooped and skidded between the waves. So it was pleasant when she stopped to greet Lady Ina (“Did you know I was on the plane with you from London? But you were sleeping so nicely I didn’t dare speak”) and seeing me remembered me: “Why, hello there, Jonesy,” she said, her rough whispery warm voice very slightly vibrating her, “how’s your sunburn? Remember, I warned you, but you wouldn’t listen.” Her laughter trailed off as she folded herself onto a banquette beside her sister, their heads inclining toward each other in whispering Bouvier conspiracy. It was puzzling how much they resembled one another without sharing any common feature beyond identical voices and wide-apart eyes and certain gestures, particularly a habit of staring deeply into an interlocutor’s eyes while ceaselessly nodding the head with a mesmerizingly solemn sympathy.

Lady Ina observed: “You can see those girls have swung a few big deals in their time. I know many people can’t abide either of them, usually women, and I can understand that, because they don’t like women and almost never have anything good to say about any woman. But they’re perfect with men, a pair of Western geisha girls; they know how to keep a man’s secrets and how to make him feel important. If I were a man, I’d fall for Lee myself. She’s marvelously made, like a Tanagra figurine; she’s feminine without being effeminate; and she’s one of the few people I’ve known who can be both candid and cozy—ordinarily one cancels the other. Jackie—no, not on the same planet. Very photogenic, of course; but the effect is a little … unrefined, exaggerated.”

I thought of an evening when I’d gone with Kate McCloud and a gang to a drag-queen contest held in a Harlem ballroom: hundreds of young queens sashaying in hand-sewn gowns to the funky honking of saxophones: Brooklyn supermarket clerks, Wall Street runners, black dishwashers and Puerto Rican waiters adrift in silk and fantasy, chorus boys and bank cashiers and Irish elevator boys got up as Marilyn Monroe, as Audrey Hepburn, as Jackie Kennedy. Indeed, Mrs. Kennedy was the most popular inspiration; a dozen boys, the winner among them, wore her high-rise hairdo, winged eyebrows, sulky, palely painted mouth. And, in life, that is how she struck me—not as a bona fide woman, but as an artful female impersonator impersonating Mrs. Kennedy.

I explained what I was thinking to Ina, and she said: “That’s what I meant by … exaggerated.” Then: “Did you ever know Rosita Winston? Nice woman. Half Cherokee, I believe. She had a stroke some years ago, and now she can’t speak. Or, rather, she can say just one word. That very often happens after a stroke, one’s left with one word out of all the words one has known. Rosita’s word is ‘beautiful.’ Very appropriate, since Rosita has always loved beautiful things. What reminded me of it was old Joe Kennedy. He, too, has been left with one word. And his word is: ‘Goddammit!’” Ina motioned the waiter to pour Champagne. “Have I ever told you about the time he assaulted me? When I was eighteen and a guest in his house, a friend of his daughter Kek…”

Again, my eye coasted the length of the room, catching, en passant, a blue-bearded Seventh Avenue brassiere hustler trying to con a closet-queen editor from The New York Times; and Diana Vreeland, the pomaded, peacock-iridescent editor of Vogue, sharing a table with an elderly man who suggested a precious object of discreet extravagance, perhaps a fine grey pearl—Mainbocher; and Mrs. William S. Paley lunching with her sister, Mrs. John Hay Whitney. Seated near them was a pair unknown to me: a woman forty, forty-five, no beauty but very handsomely set up inside a brown Balenciaga suit with a brooch composed of cinnamon-colored diamonds fixed to the lapel. Her companion was much younger, twenty, twenty-two, a hearty sun-browned statue who looked as if he might have spent the summer sailing alone across the Atlantic. Her son? But no, because ... he lit a cigarette and passed it to her and their fingers touched significantly; then they were holding hands.

“…the old bugger slipped into my bedroom. It was about six o’clock in the morning, the ideal hour if you want to catch someone really slugged out, really by complete surprise, and when I woke up he was already between the sheets with one hand over my mouth and the other all over the place. The sheer ballsy gall of it-—right there in his own house with the whole family sleeping all around us. But all those Kennedy men are the same; they’re like dogs, they have to pee on every fire hydrant. Still, you had to give the old guy credit, and when he saw I wasn’t going to scream he was so grateful….”

But they were not conversing, the older woman and the young seafarer; they held hands, and then he smiled and presently she smiled, too.

“Afterward, can you imagine? he pretended nothing had happened, there was never a wink or a nod, just the good old daddy of my schoolgirl chum. It was uncanny and rather cruel; after all, he’d had me and I’d even pretended to enjoy it: there should have been some sentimental acknowledgment, a bauble, a cigarette box….” She sensed my other interest, and her eyes strayed to the improbable lovers. She said: “Do you know that story?”

“No,” I said. “But I can see there has to be one.”

“Though it’s not what you think. Uncle Willie could have made something divine out of it. So could Henry James—better than Uncle Willie, because Uncle Willie would have cheated, and, for the sake of a movie sale, would have made Delphine and Bobby lovers.”

Delphine Austin from Detroit; I’d read about her in the columns—an heiress married to a marbleized pillar of New York clubman society. Bobby, her companion, was Jewish, the son of hotel magnate S.L.L. Semenenko and first husband of a weird young movie cutie who had divorced him to marry his father (and whom the father had divorced when he caught her in flagrante with a German shepherd—dog. I’m not kidding).

According to Lady Ina, Delphine Austin and Bobby Semenenko had been inseparable the past year or so, lunching every day at Côte Basque and Lutèce and L’Aiglon, traveling in winter to Gstaad and Lyford Cay, skiing, swimming, spreading themselves with utmost vigor considering the bond was not June-and-January frivolities but really the basis for a double-bill, double-barreled, three-handkerchief variation on an old Bette Davis weeper like Dark Victory: they both were dying of leukemia.

“I mean, a worldly woman and a beautiful young man who travel together with death as their common lover and companion. Don’t you think Henry James could have done something with that? Or Uncle Willie?”

“No. It’s too corny for James, and not corny enough for Maugham.”

“Well, you must admit, Mrs. Hopkins would make a fine tale.”

“Who?” I said.

“Standing there,” Ina Coolbirth said.

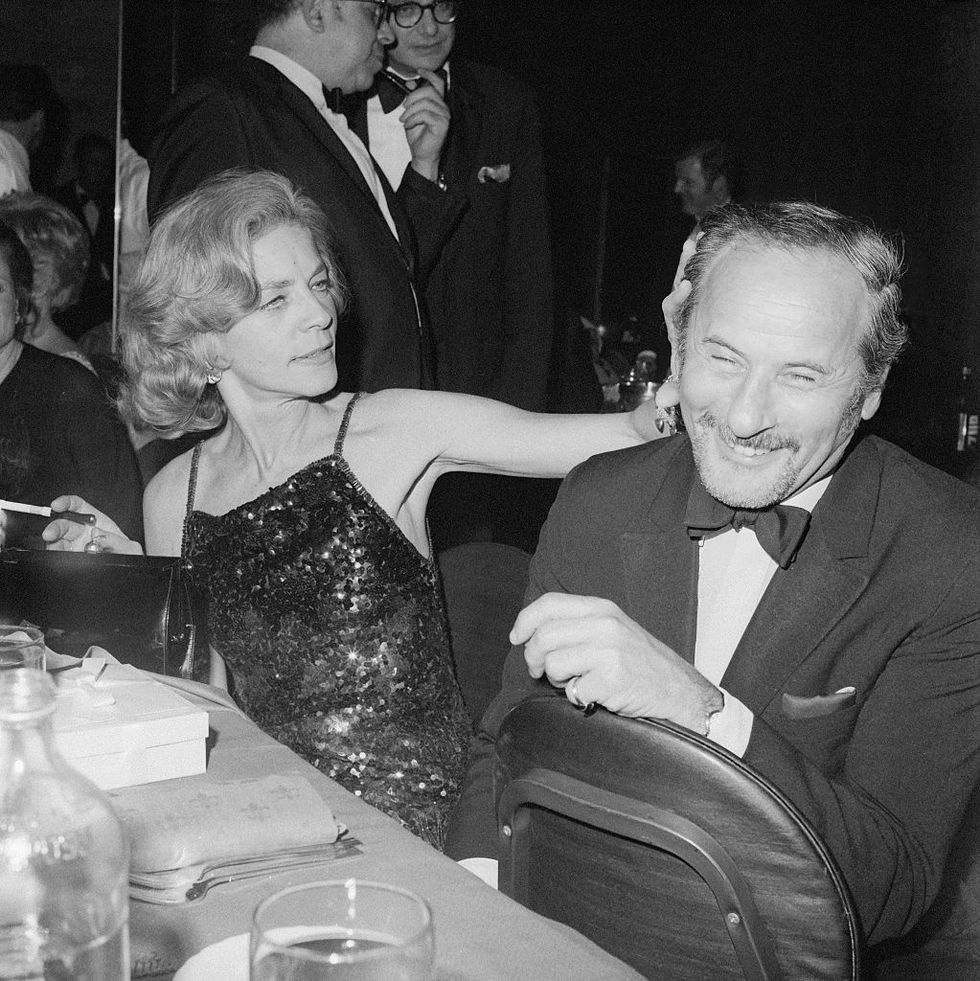

That Mrs. Hopkins. A redhead dressed in black; black hat with a veil trim, a black Mainbocher suit, black crocodile purse, crocodile shoes. M. Soulé had an ear cocked as she stood whispering to him; and suddenly everyone was whispering. Mrs. Kennedy and her sister had elicited not a murmur, nor had the entrances of Lauren Bacall and Katharine Cornell and Clare Boothe Luce. However, Mrs. Hopkins was une autre chose: a sensation to unsettle the suavest Côte Basque client. There was nothing surreptitious in the attention allotted her as she moved with head bowed toward a table where an escort already awaited her—a Catholic priest, one of those high-brow, malnutritional, Father D’Arcy clerics who always seems most at home when absent from the cloisters and while consorting with the very grand and very rich in a wine-and-roses stratosphere.

“Only,” said Lady Ina, “Ann Hopkins would think of that. To advertise your search for spiritual ‘advice’ in the most public possible manner. Once a tramp, always a tramp.”

“You don’t think it was an accident?” I said.

“Come out of the trenches, boy. The war’s over. Of course it wasn’t an accident. She killed David with malice aforethought. She’s a murderess. The police know that.”

“Then how did she get away with it?”

“Because the family wanted her to. David’s family. And, as it happened in Newport, old Mrs. Hopkins had the power to prevail. Have you ever met David’s mother? Hilda Hopkins?”

“I saw her once last summer in Southampton. She was buying a pair of tennis shoes. I wondered what a woman her age, she must be eighty, wanted with tennis shoes. She looked like—some very old goddess.”

“She is. That’s why Ann Hopkins got away with cold-blooded murder. Her mother-in-law is a Rhode Island goddess. And a saint.”

Ann Hopkins had lifted her veil and was now whispering to the priest who, servilely entranced, was brushing a Gibson against his starved blue lips.

“But it could have been an accident. If one goes by the papers. As I remember, they’d just come home from a dinner party in Watch Hill and gone to bed in separate rooms. Weren’t there supposed to have been a recent series of burglaries thereabouts?—and she kept a shotgun by her bed, and suddenly in the dark her bedroom door opened and she grabbed the shotgun and shot at what she thought was a prowler. Only it was her husband. David Hopkins. With a hole through his head.”

“That’s what she said. That’s what her lawyer said. That’s what the police said. And that’s what the papers said … even The Times. But that isn’t what happened.” And Ina, inhaling like a skin diver, began: “Once upon a time a jazzy little carrottop killer rolled into town from Wheeling or Logan—somewhere in West Virginia. She was eighteen, she’d been brought up in some country-slum way, and she had already been married and divorced; or she said she’d been married a month or two to a Marine and divorced him when he disappeared (keep that in mind: it’s an important clue). Her name was Ann Cutler, and she looked rather like a malicious Betty Grable. She worked as a call girl for a pimp who was a bell captain at the Waldorf; and she saved her money and took voice lessons and dance lessons and ended up as the favorite lay of one of Frankie Costello’s shysters, and he always took her to El Morocco. It was during the war—1943—and Elmer’s was always full of gangsters and military brass. But one night an ordinary young Marine showed up there; except that he wasn’t ordinary: his father was one of the stuffiest men in the East—and richest.

David had sweetness and great good looks, but he was just like old Mr. Hopkins really—an anal-oriented Episcopalian. Stingy. Sober. Not at all café society. But there he was at Elmer’s, a soldier on leave, horny and a bit stoned. One of Winchell’s stooges was there, and he recognized the Hopkins boy; he bought David a drink, and said he could fix it up for him with any one of the girls he saw, just pick one, and David, poor sod, said the redhead with the button nose and big tits was okay by him. So the Winchell stooge sends her a note, and at dawn little David finds himself writhing inside the grip of an expert Cleopatra’s clutch. I’m sure it was David’s first experience with anything less primitive than a belly rub with his prep-school roomie. He went bonkers, not that one can blame him; I know some very grown-up Mr. Cool Balls who’ve gone bonkers over Ann Hopkins. She was clever with David; she knew she’d hooked a biggie, even if he was only a kid, so she quit what she was doing and got a job in lingerie at Saks; she never pressed for anything, refused any gift fancier than a handbag, and all the while he was in the service she wrote him every day, little letters cozy and innocent as a baby’s layette. In fact, she was knocked up; and it was his kid; but she didn’t tell him a thing until he next came home on leave and found his girl four months pregnant.

Now here is where she showed that certain venomous élan that separates truly dangerous serpents from mere chicken snakes: she told him she didn’t want to marry him. Wouldn’t marry him under any circumstances because she had no desire to lead a Hopkins life; she had neither the background nor innate ability to cope with it, and she was sure neither his family nor friends would ever accept her. She said all she would ever ask would be a modest amount of child support. David protested, but of course he was relieved, even though he would still have to go to his father with the story—David had no money of his own. It was then that Ann made her smartest move; she had been doing her homework, and she knew everything there was to know about David’s parents; so she said: ‘David, there’s just one thing I’d like. I want to meet your family. I never had much family of my own, and I’d like my child to have some occasional contact with his grandparents. They might like that, too.’ C’est très joli, très diabolique, non? And it worked. Not that Mr. Hopkins was fooled. Right from the start he said the girl was a tramp, and she would never see a nickel of his; but Hilda Hopkins fell for it—she believed that gorgeous hair and those blue malarkey eyes, the whole poor-little-match-girl pitch Ann was tossing her. And as David was the oldest son, and she was in a hurry for a grandchild, she did exactly what Ann had gambled on: she persuaded David to marry her, and her husband to, if not condone it, at least not forbid it. And for some while it seemed as if Mrs. Hopkins had been very wise: each year she was rewarded with another grandchild until there were three, two girls and a boy; and Ann’s social pickup was incredibly quick—she crashed right through, not bothering to observe any speed limits. She certainly grasped the essentials, I’ll say that. She learned to ride and became the horsiest horse-hag in Newport. She studied French and had a French butler and campaigned for the Best Dressed List by lunching with Eleanor Lambert and inviting her for weekends. She learned about furniture and fabrics from Sister Parish and Billy Baldwin; and little Henry Geldzahler was pleased to come to tea (Tea! Ann Cutler! My God!) and to talk to her about modern paintings. But the deciding element in her success, leaving aside the fact she’d married a great Newport name, was the duchess. Ann realized something that only the cleverest social climbers ever do. If you want to ride swiftly and safely from the depths to the surface, the surest way is to single out a shark and attach yourself to it like a pilot fish. This is as true in Keokuk, where one massages, say, the local Mrs. Ford Dealer, as it is in Detroit, where you may as well try for Mrs. Ford herself—or in Paris or Rome. But why should Ann Hopkins, being by marriage a Hopkins and the daughter-in-law of the Hilda Hopkins, need the duchess? Because she needed the blessing of someone with presumably high standards, someone with international impact whose acceptance of her would silence the laughing hyenas. And who better than the duchess? As for the duchess, she has high tolerance for the flattery of rich ladies-in-waiting, the kind who always pick up the check; I wonder if the duchess has ever picked up a check. Not that it matters. She gives good value. She’s one of that unusual female breed who are able to have a genuine friendship with another woman. Certainly she was a marvelous friend to Ann Hopkins. Of course she wasn’t taken in by Ann—after all, the duchess is too much of a con artist not to twig another one; but the idea amused her of taking this cool-eyed card-player and lacquering her with a little real style, launching her on the circuit, and the young Mrs. Hopkins became quite notorious—though without the style. The father of the second Hopkins girl was Fon Portago, or so everyone says, and God knows she does look very espagnole; however that may be, Ann Hopkins was definitely racing her motor in the Grand Prix manner.

One summer she and David took a house at Cap Ferrat (she was trying to worm her way in with Uncle Willie: she even learned to play first-class bridge; but Uncle Willie said that while she was a woman he might enjoy writing about, she was not someone he trusted to have at his card table), and from Nice to Monte she was known by every male past puberty as Madame Marmalade—her favorite petit déjeuner being hot cock buttered with Dundee’s best. Although I’m told it’s actually strawberry jam she prefers. I don’t think David guessed the full measure of these fandangos, but there was no doubt he was miserable, and after a while he fell in with the very girl he ought to have married originally—his second cousin, Mary Kendall, no beauty but a sensible, attractive girl who had always been in love with him. She was engaged to Tommy Bedford but broke it off when David asked her to marry him. If he could get a divorce. And he could; all it would cost him, according to Ann, was five million dollars tax-free. David still had no glue of his own, and when he took this proposition to his father, Mr. Hopkins said never! and said he’d always warned that Ann was what she was, bad baggage, but David hadn’t listened, so now that was his burden, and as long as the father lived she would never get a subway token. After this, David hired a detective and within six months had enough evidence, including Polaroids of her being screwed front and back by a couple of jockeys in Saratoga, to have her jailed, much less divorce her. But when David confronted her, Ann laughed and told him his father would never allow him to take such filth into court. She was right. It was interesting, because when discussing the matter, Mr. Hopkins told David that, under the circumstances, he wouldn’t object to the son killing the wife, then keeping his mouth shut, but certainly David couldn’t divorce her and supply the press with that kind of manure.

“It was at this point that David’s detective had an inspiration; an unfortunate one, because if it had never come about, David might still be alive. However, the detective had an idea: he searched out the Cutler homestead in West Virginia—or was it Kentucky?—and interviewed relatives who had never heard from her after she’d gone to New York, had never known her in her grand incarnation as Mrs. David Hopkins but simply as Mrs. Billy Joe Barnes, the wife of a hillbilly jarhead. The detective got a copy of the marriage certificate from the local courthouse, and after that he tracked down this Billy Joe Barnes, found him working as an airplane mechanic in San Diego, and persuaded him to sign an affidavit saying he had married one Ann Cutler, never divorced her, not remarried, that he simply had returned from Okinawa to find she had disappeared, but as far as he knew she was still Mrs. Billy Joe Barnes. Indeed she was!—even the cleverest criminal minds have a basic stupidity. And when David presented her with the information and said to her: ‘Now we’ll have no more of those round-figure ultimatums, since we’re not legally married,’ surely it was then she decided to kill him: a decision made by her genes, the inescapable white-trash slut inside her, even though she knew the Hopkinses would arrange a respectable ‘divorce’ and provide a very good allowance; but she also knew if she murdered David, and got away with it, she and her children would eventually receive his inheritance, something that wouldn’t happen if he married Mary Kendall and had a second family. So she pretended to acquiesce and told David there was no point arguing as he obviously had her by the snatch, but would he continue to live with her for a month while she settled her affairs? He agreed, idiot; and immediately she began preparing the legend of the prowler—twice she called police, claiming a prowler was on the grounds; soon she had the servants and most of the neighbors convinced that prowlers were everywhere in the vicinity, and actually Nini Wolcott’s house was broken into, presumably by a burglar, but now even Nini admits that Ann must have done it. As you may recall, if you followed the case, the Hopkinses went to a party at the Wolcotts’ the night it happened.

A Labor Day dinner dance with about fifty guests; I was there, and I sat next to David at dinner. He seemed very relaxed, full of smiles, I suppose because he thought he’d soon be rid of the bitch and married to his cousin Mary; but Ann was wearing a pale green dress, and she seemed almost green with tension—she chattered on like a lunatic chimpanzee about prowlers and burglars and how she always slept now with a shotgun by her bedside. According to The Times, David and Ann left the Wolcotts’ a bit after midnight, and when they reached home, where the servants were on holiday and the children staying with their grandparents in Bar Harbor, they retired to separate bedrooms. Ann’s story was, and is, that she went straight to sleep but was wakened within half an hour by the noise of her bedroom door opening: she saw a shadowy figure—the prowler! She grabbed her shotgun and in the dark fired away, emptying both barrels. Then she turned on the lights and, oh, horror of horrors, discovered David sprawled in the hallway nicely cooled. But that isn’t where the cops found him. Because that isn’t where or how he was killed. The police found the body inside a glassed-in shower, naked. The water was still running, and the shower door was shattered with bullets.”

“In other words—” I began.

“In other words—” Lady Ina picked up but waited until a captain, supervised by a perspiring M. Soulé, had finished ladling out the soufflé Furstenberg “—none of Ann’s story was true. God knows what she expected people to believe; but she just, after they reached home and David had stripped to take a shower, followed him there with a gun and shot him through the shower door. Perhaps she intended to say the prowler had stolen her shotgun and killed him. In that case, why didn’t she call a doctor, call the police? Instead, she telephoned her lawyer. Yes. And he called the police. But not until after he had called the Hopkinses in Bar Harbor.”

The priest was swilling another Gibson; Ann Hopkins, head bent, was still whispering at him confessionally. Her waxy fingers, unpainted and unadorned except for a stark gold wedding band, nibbled at her breast as though she were reading rosary beads.

“But if the police knew the truth—”

“Of course they knew.”

“Then I don’t see how she got away with it. It’s not conceivable.”

“I told you,” Ina said tartly, “she got away with it because Hilda Hopkins wanted her to. It was the children: tragic enough to have lost their father, what purpose could it serve to see the mother convicted of murder? Hilda Hopkins, and old Mr. Hopkins, too, wanted Ann to go scot-free; and the Hopkinses, within their terrain, have the power to brainwash cops, reweave minds, move corpses from shower stalls to hallways; the power to control inquests—David’s death was declared an accident at an inquest that lasted less than a day.” She looked across at Ann Hopkins and her companion—the latter, his clerical brow scarlet with a two-cocktail flush, not listening now to the imploring murmur of his patroness but staring rather glassy-gaga at Mrs. Kennedy, as if any moment he might run amok and ask her to autograph a menu. “Hilda’s behavior has been extraordinary. Flawless. One would never suspect she wasn’t truly the affectionate, grieving protector of a bereaved and very legitimate widow. She never gives a dinner party without inviting her. The one thing I wonder is what everyone wonders—when they’re alone, just the two of them, what do they talk about?” Ina selected from her salad a leaf of Bibb lettuce, pinned it to a fork, studied it through her black spectacles. “There is at least one respect in which the rich, the really very rich, are different from … other people. They understand vegetables. Other people—well, anyone can manage roast beef, a great steak, lobsters. But have you ever noticed how, in the homes of the very rich, at the Wrightsmans’ or Dillons’, at Bunny’s and Babe’s, they always serve only the most beautiful vegetables, and the greatest variety? The greenest petits pois, infinitesimal carrots, corn so baby-kerneled and tender it seems almost unborn, lima beans tinier than mice eyes, and the young asparagus! the limestone lettuce! the raw red mushrooms! zucchini….” Lady Ina was feeling her Champagne.

Mrs. Matthau and Mrs. Cooper lingered over café filtre. “I know,” mused Mrs. Matthau, who was analyzing the wife of a midnight-TV clown/hero, “Jane is pushy: all those telephone calls—Christ, she could dial Answer Prayer and talk an hour. But she’s bright, she’s fast on the draw, and when you think what she has to put up with. This last episode she told me about: hair-raising. Well, Bobby had a week off from the show—he was so exhausted he told Jane he wanted just to stay home, spend the whole week slopping around in his pajamas, and Jane was ecstatic; she bought hundreds of magazines and books and new LP’s and every kind of goody from Maison Glass. Oh, it was going to be a lovely week. Just Jane and Bobby sleeping and screwing and having baked potatoes with caviar for breakfast. But after one day he evaporated. Didn’t come home that night or call. It wasn’t the first time, Jesus be, but Jane was out of her mind. Still, she couldn’t report it to the police; what a sensation that would be. Another day passed, and not a word. Jane hadn’t slept for forty-eight hours. Around three in the morning the phone rang. Bobby. Smashed. She said: ‘My God, Bobby, where are you?’ He said he was in Miami, and she said, losing her temper now, how the fuck did you get in Miami, and he said, oh, he’d gone to the airport and taken a plane, and she said what the fuck for, and he said just because he felt like being alone. Jane said: ‘And are you alone?’ Bobby, you know what a sadist he is behind that huckleberry grin, said: ‘No. There’s someone lying right here. She’d like to speak to you.’ And on comes this scared little giggling peroxide voice: ‘Really, is this really Mrs. Baxter, hee hee? I thought Bobby was making a funny, hee hee. We just heard on the radio how it was snowing there in New York—I mean, you ought to be down here with us where it’s ninety degrees!’ Jane said, very chiseled: ‘I’m afraid I’m much too ill to travel.’ And peroxide, all fluttery distress: ‘Oh, gee, I’m sorry to hear that. What’s the matter, honey?’ Jane said: ‘I’ve got a double dose of syph and the old clap-clap, all courtesy of that great comic, my husband, Bobby Baxter—and if you don’t want the same I suggest you get the hell out of there.’ And she hung up.”

Mrs. Cooper was amused, though not very; puzzled rather. “How can any woman tolerate that? I’d divorce him.”

“Of course you would. But, then, you’ve got the two things Jane hasn’t.”

“Ah?”

“One: dough. And two: identity.”

Lady Ina was ordering another bottle of Cristal. “Why not?” she asked, defiantly replying to my concerned expression. “Easy up, Jonesy. You won’t have to carry me piggyback. I just feel like it: shattering the day into golden pieces.” Now, I thought, she’s going to tell me what she wants, but doesn’t want, to tell me. But no, not yet. Instead: “Would you care to hear a truly vile story? Really vomitous? Then look to your left. That sow sitting next to Betsy Whitney.”

She was somewhat porcine, a swollen muscular baby with a freckled Bahamas-burnt face and squinty-mean eyes; she looked as if she wore tweed brassieres and played a lot of golf.

“The governor’s wife?”

“The governor’s wife,” said Ina, nodding as she gazed with melancholy contempt at the homely beast, legal spouse of a former New York governor. “Believe it or not, but one of the most attractive guys who ever filled a pair of trousers used to get a hard-on every time he looked at that bull dyke. Sidney Dillon—” the name, pronounced by Ina, was a caressing hiss.

To be sure. Sidney Dillon. Conglomateur, adviser to Presidents, an old flame of Ina’s. I remember once picking up a copy of what was, after the Bible and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Ina’s favorite book, Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa; from between the pages fell a Polaroid picture of a swimmer standing at water’s edge, a wiry well-constructed man with a hairy chest and a twinkle-grinning tough-Jew face; his bathing trunks were rolled to his knees, one hand rested sexily on a hip, and with the other he was pumping a dark fat mouth-watering dick. On the reverse side a notation, made in Ina’s boyish script, read: Sidney. Lago di Garda. En route to Venice. June, 1962.

“Dill and I have always told each other everything. He was my lover for two years when I was just out of college and working at Harper’s Bazaar. The only thing he ever specifically asked me never to repeat was this business about the governor’s wife; I’m a bitch to tell it, and maybe I wouldn’t if it wasn’t for all these blissful bubbles risin’ in my noggin—” She lifted her Champagne and peered at me through its sunny effervescence.

“Gentlemen, the question is: why would an educated, dynamic, very rich and well-hung Jew go bonkers for a cretinous Protestant size forty who wears low-heeled shoes and lavender water? Especially when he’s married to Cleo Dillon, to my mind the most beautiful creature alive, always excepting the Garbo of even ten years ago (incidentally, I saw her last night at the Gunthers’, and I must say the whole setup has taken on a very weathered look, dry and drafty, like an abandoned temple, something lost in the jungles at Angkor Wat; but that’s what happens when you spend most of a life loving only yourself, and that not very much). Dill’s in his sixties now; he could still have any woman he wants, yet for years he yearned after yonder porco. I’m sure he never entirely understood this ultra-perversion, the reason for it; or if he did he never would admit it, not even to an analyst—that’s a thought! Dill at an analyst! Men like that can never be analyzed because they don’t consider any other man their equal. But as for the governor’s wife, it was simply that for Dill she was the living incorporation of everything denied him, forbidden to him as a Jew, no matter how beguiling and rich he might be: the Racquet Club, Le Jockey, the Links, White’s—all those places he would never sit down to a table of backgammon, all those golf courses where he would never sink a putt—the Everglades and the Seminole, the Maidstone, and St. Paul’s and St. Mark’s et al., the saintly little New England schools his sons would never attend. Whether he confesses to it or not, that’s why he wanted to fuck the governor’s wife, revenge himself on that smug hog-bottom, make her sweat and squeal and call him daddy. He kept his distance, though, and never hinted at any interest in the lady, but waited for the moment when the stars were in their correct constellation.

It came unplanned—one night he went to a dinner party at the Cowleses’; Cleo had gone to a wedding in Boston. The governor’s wife was seated next to him at dinner; she, too, had come alone, the governor off campaigning somewhere. Dill joked, he dazzled; she sat there pig-eyed and indifferent, but she didn’t seem surprised when he rubbed his leg against hers, and when he asked if he might see her home she nodded, not with much enthusiasm but with a decisiveness that made him feel she was ready to accept whatever he proposed. At that time Dill and Cleo were living in Greenwich; they’d sold their town house on Riverview Terrace and had only a two-room pied-à-terre at the Pierre, just a living room and a bedroom. In the car, after they’d left the Cowleses’, he suggested they stop by the Pierre for a nightcap: he wanted her opinion of his new Bonnard. She said she would be pleased to give her opinion; and why shouldn’t the idiot have one? Wasn’t her husband on the board of directors at the Modern? When she’d seen the painting, he offered her a drink, and she said she’d like a brandy; she sip-sipped it, sitting opposite him across a coffee table, nothing at all happening between them, except that suddenly she was very talkative—about the horse sales in Saratoga, and a hole-by-hole golf game she’d played with Doc Holden at Lyford Cay; she talked about how much money Joan Payson had won from her at bridge and how the dentist she’d used since she was a little girl had died and now she didn’t know what to do with her teeth; oh, she jabbered on until it was almost two, and Dill kept looking at his watch, not only because he’d had a long day and was anxious but because he expected Cleo back on an early plane from Boston: she’d said she would see him at the Pierre before he left for the office. So eventually, while she was rattling on about root canals, he shut her up: ‘Excuse me, my dear, but do you want to fuck or not?’ There is something to be said for aristocrats, even the stupidest have had some kind of class bred into them; so she shrugged—‘Well, yes, I suppose so’—as though a salesgirl had asked if she liked the look of a hat. Merely resigned, as it were, to that old familiar hard-sell Jewish effrontery. In the bedroom she asked him not to turn on the lights. She was quite firm about that—and in view of what finally transpired, one can scarcely blame her. They undressed in the dark, and she took forever—unsnapping, untying, unzipping—and said not a word except to remark on the fact that the Dillons obviously slept in the same bed since there was only the one; and he told her yes, he was affectionate, a mama’s boy who couldn’t sleep unless he had something soft to cuddle against. The governor’s wife was neither a cuddler nor a kisser. Kissing her, according to Dill, was like playing post office with a dead and rotting whale: she really did need a dentist. None of his tricks caught her fancy, she just lay there, inert, like a missionary being outraged by a succession of sweating Swahilis. Dill couldn’t come. He felt as though he were sloshing around in some strange puddle, the whole ambience so slippery he couldn’t get a proper grip. He thought maybe if he went down on her—but the moment he started to, she hauled him up by his hair: ‘Nonnonono, for God’s sake, don’t do that!’ Dill gave up, he rolled over, he said: ‘I don’t suppose you’d blow me?’ She didn’t bother to reply, so he said okay, all right, just jack me off and we’ll call it scratch, okay? But she was already up, and she asked him please not to turn on the light, please, and she said no, he need not see her home, stay where he was, go to sleep, and while he lay there listening to her dress he reached down to finger himself, and it felt ... it felt ... he jumped up and snapped on the light. His whole paraphernalia had felt sticky and strange. As though it were covered with blood. As it was. So was the bed. The sheets bloodied with stains the size of Brazil. The governor’s wife had just picked up her purse, had just opened the door, and Dill said: ‘What the hell is this? Why did you do it?’ Then he knew why, not because she told him, but because of the glance he caught as she closed the door: like Carino, the cruel maître d’ at the old Elmer’s—leading some blue-suit brown-shoes hunker to a table in Siberia. She had mocked him, punished him for his Jewish presumption.

“Jonesy, you’re not eating?”

“It isn’t doing much for my appetite. This conversation.”

“I warned you it was a vile story. And we haven’t come to the best part yet.”

“All right. I’m ready.”

“No, Jonesy. Not if it’s going to make you sick.”

“I’ll take my chances,” I said.

Mrs. Kennedy and her sister had left; the governor’s wife was leaving, Soulé beaming and bobbing in her wide-hipped wake. Mrs. Matthau and Mrs. Cooper were still present but silent, their ears perked to our conversation; Mrs. Matthau was kneading a fallen yellow rose petal—her fingers stiffened as Ina resumed: “Poor Dill didn’t realize the extent of his difficulties until he’d stripped the sheets off the bed and found there were no clean ones to replace them. Cleo, you see, used the Pierre’s linen and kept none of her own at the hotel. It was three o’clock in the morning and he couldn’t reasonably call for maid service: what would he say, how could he explain the loss of his sheets at that hour? The particular hell of it was that Cleo would be sailing in from Boston in a matter of hours, and regardless of how much Dill screwed around he’d always been scrupulous about never giving Cleo a clue; he really loved her, and, my God, what could he say when she saw that bed? He took a cold shower and tried to think of some buddy he could call and ask to hustle over with a change of sheets. There was me, of course; he trusted me, but I was in London. And there was his old valet, Wardell. Wardell was queer for Dill and had been a slave for twenty years just for the privilege of soaping him whenever Dill took his bath; but Wardell was old and arthritic, Dill couldn’t call him in Greenwich and ask him to drive all the way in to town. Then it struck him that he had a hundred chums but really no friends, not the kind you ring at three in the morning. In his own company he employed more than six thousand people, but there was not one who had ever called him anything except Mr. Dillon. I mean, the guy was feeling sorry for himself. So he poured a truly stiff Scotch and started searching in the kitchen for a box of laundry soap, but he couldn’t find any and in the end had to use a bar of Guerlain’s Fleurs des Alpes. To wash the sheets. He soaked them in the tub in scalding water. Scrubbed and scrubbed. Rinsed and scrubadubdubbed. There he was, the powerful Mr. Dillon, down on his knees and flogging away like a Spanish peasant at the side of a stream. It was five o’clock, it was six, the sweat poured off him, he felt as if he were trapped in a sauna; he said the next day when he weighed himself he’d lost eleven pounds. Full daylight was upon him before the sheets looked credibly white. But wet. He wondered if hanging them out the window might help—or merely attract the police? At last he thought of drying them in the kitchen oven. It was only one of those little hotel stoves, but he stuffed them in and set them to bake at four hundred fifty degrees. And they baked, brother: smoked and steamed—the bastard burned his hand pulling them out. Now it was eight o’clock and there was no time left. So he decided there was nothing to do but make up the bed with the steamy soggy sheets, climb between them and say his prayers. He really was praying when he started to snore. When he woke up it was noon, and there was a note on the bureau from Cleo: ‘Darling, you were sleeping so soundly and sweetly that I just tiptoed in and changed and have gone on to Greenwich. Hurry home.’ ”

The Mesdames Cooper and Matthau, having heard their fill, self-consciously prepared to depart.

Mrs. Cooper said: “D-darling, there’s the most m-m-marvelous auction at Parke Bernet this afternoon—Gothic tapestries.”

“What the fuck,” asked Mrs. Matthau, “would I do with a Gothic tapestry?”

Mrs. Cooper replied: “I thought they might be amusing for picnics at the beach. You know, spread them on the sands.”

Lady Ina, after extracting from her purse a Bulgari vanity case made of white enamel sprinkled with diamond flakes, an object remindful of snow prisms, was dusting her face with a powder puff. She started with her chin, moved to her nose, and the next thing I knew she was slapping away at the lenses of her dark glasses.

And I said, “What are you doing, Ina?”

She said: “Damn! damn!” and pulled off the glasses and mopped them with a napkin. A tear had slid down to dangle like sweat at the tip of a nostril—not a pretty sight; neither were her eyes—red and veined from a heap of sleepless weeping. “I’m on my way to Mexico to get a divorce.”

One wouldn’t have thought that would make her unhappy; her husband was the stateliest bore in England, an ambitious achievement, considering some of the competition: the Earl of Derby, the Duke of Marlborough, to name but two. Certainly that was Lady Ina’s opinion; still, I could understand why she married him—he was rich, he was technically alive, he was a “good gun” and for that reason reigned in hunting circles, boredom’s Valhalla. Whereas Ina … Ina was fortyish and a multiple divorcée on the rebound from an affair with a Rothschild who had been satisfied with her as a mistress but hadn’t thought her grand enough to wed. So Ina’s friends were relieved when she returned from a shoot in Scotland engaged to Lord Coolbirth; true, the man was humorless, dull, sour as port decanted too long—but, all said and done, a lucrative catch.

“I know what you’re thinking,” Ina remarked, amid more tearful trickling. “That if I’m getting a good settlement I ought to be congratulated. I don’t deny Cool was tough to take. Like living with a suit of armor. But I did … feel safe. For the first time I felt I had a man I couldn’t possibly lose. Who else would want him? But I’ve now learned this, Jonesy, and hark me well: there’s always someone around to pick up an old husband. Always.” A crescendo of hiccups interrupted her: M. Soulé, observing from a concealed distance, pursed his lips. “I was careless. Lazy. But I just couldn’t bear any more of those wet Scottish weekends with the bullets whizzing round, so he started going alone, and after a while I began to notice that everywhere he went Elda Morris was sure to go—whether it was a grouse shoot in the Hebrides or a boar hunt in Yugoslavia. She even tagged along to Spain when Franco gave that huge hunting party last October. But I didn’t make too much of it—Elda’s a great gun, but she’s also a hard-boiled fifty-year-old virgin; I still can’t conceive of Cool wanting to get into those rusty knickers.” Her hand weaved toward the Champagne glass but, without arriving at its destination, drooped and fell like a drunk suddenly sprawling flat on the street. “Two weeks ago,” she began, her voice slowed, her Montana accent becoming more manifest, “as Cool and I were winging to New York, I realized that he was staring at me with a, hmnnn, serpentine scowl. Ordinarily he looks like an egg. It was only nine in the morning; nevertheless, we were drinking that loathsome airplane champagne, and when we’d finished a bottle and I saw he was still looking at me in this … homicidal … way, I said: ‘What’s bugging you, Cool?’ And he said: ‘Nothing that a divorce from you wouldn’t cure.’ Imagine the wickedness of it! springing something like that on a plane!—when you’re stuck together for hours, and can’t get away, can’t shout or scream. It was doubly nasty of him because he knows I’m terrified of flying—he knew I was full of pills and booze. So now I’m on my way to Mexico.”

At last her hand retrieved the glass of Cristal; she sighed, a sound despondent as spiraling autumn leaves. “My kind of woman needs a man. Not for sex. Oh, I like a good screw. But I’ve had my share; I can do without it. But I can’t live without a man. Women like me have no other focus, no other way of scheduling our lives; even if we hate him, even if he’s an iron head with a cotton heart, it’s better than this footloose routine. Freedom may be the most important thing in life, but there’s such a thing as too much freedom. And I’m the wrong age now, I can’t face all that again, the long hunt, the sitting up all night at Elmer’s or Annabel’s with some fat greaser swimming in a sea of stingers. All the old gal pals asking you to their little black-tie dinners and not really wanting an extra woman and wondering where they’re going to find a ‘suitable’ extra man for an aging broad like Ina Coolbirth. As though there were any suitable extra men in New York. Or London. Or Butte, Montana, if it comes to that. They’re all queer. Or ought to be. That’s what I meant when I told Princess Margaret it was too bad she didn’t like fags because it meant she would have a very lonely old age. Fags are the only people who are kind to worldly old women; and I adore them, I always have, but I really am not ready to become a full-time fag’s moll; I’d rather go dyke. No, Jonesy, that’s never been part of my repertoire, but I can see the appeal for a woman my age, someone who can’t abide loneliness, who needs comfort and admiration: some dykes can ladle it out good. There’s nothing cozier or safer than a nice little lez-nest. I remember when I saw Anita Hohnsbeen in Santa Fe. How I envied her. But I’ve always envied Anita. She was a senior at Sarah Lawrence when I was a freshman. I think everyone had a crush on Anita. She wasn’t beautiful, even pretty, but she was so bright and nerveless and clean—her hair, her skin, she always looked like the first morning on earth. If she hadn’t had all that glue, and if that climbing Southern mother of hers had stopped pushing her, I think she would have married an archaeologist and spent a happy lifetime excavating urns in Anatolia. But why disinter Anita’s wretched history?—five husbands and one retarded child, just a waste until she’d had several hundred breakdowns and weighed ninety pounds and her doctor sent her out to Santa Fe. Did you know Santa Fe is the dyke capital of the United States? What San Francisco is to les garçons, Santa Fe is to the Daughters of Bilitis. I suppose it’s because the butchier ones like dragging up in boots and denim. There’s a delicious woman there, Megan O’Meaghan, and Anita met her and, baby, that was it. All she’d ever needed was a good pair of motherly tits to suckle. Now she and Megan live in a rambling adobe in the foothills, and Anita looks … almost as clear-eyed as she did when we were at school together. Oh, it’s a bit corny—the piñon fires, the Indian fetish dolls, Indian rugs, and the two ladies fussing in the kitchen over homemade tacos and the ‘perfect’ Margarita. But say what you will, it’s one of the pleasantest homes I’ve ever been in. Lucky Anita!”

She lurched upward, a dolphin shattering the surface of the sea, pushed back the table (overturning a Champagne glass), seized her purse, said: “Be right back”; and careened toward the mirrored door of the Côte Basque powder room.

Although the priest and the assassin were still whispering and sipping at their table, the restaurant’s rooms had emptied, M. Soulé had retired. Only the hatcheck girl and a few waiters impatiently flicking napkins remained. Stewards were resetting the tables, sprucing the flowers for the evening visitors. It was an atmosphere of luxurious exhaustion, like a ripened, shedding rose, while all that waited outside was the failing New York afternoon.