Antarctica 2018: Chapter 18: A Hui Hui Kākou and Aloha

Link to Chapter 17: McMurdo, The Big Town of Antarctica

Link to Chapter 16: To All Points North

Link to Chapter 15: The South Pole Traverse Arrives

Link to Chapter 14: Two pictures to sum it all up.

Link to Chapter 13: Visual tour of South Pole Station.

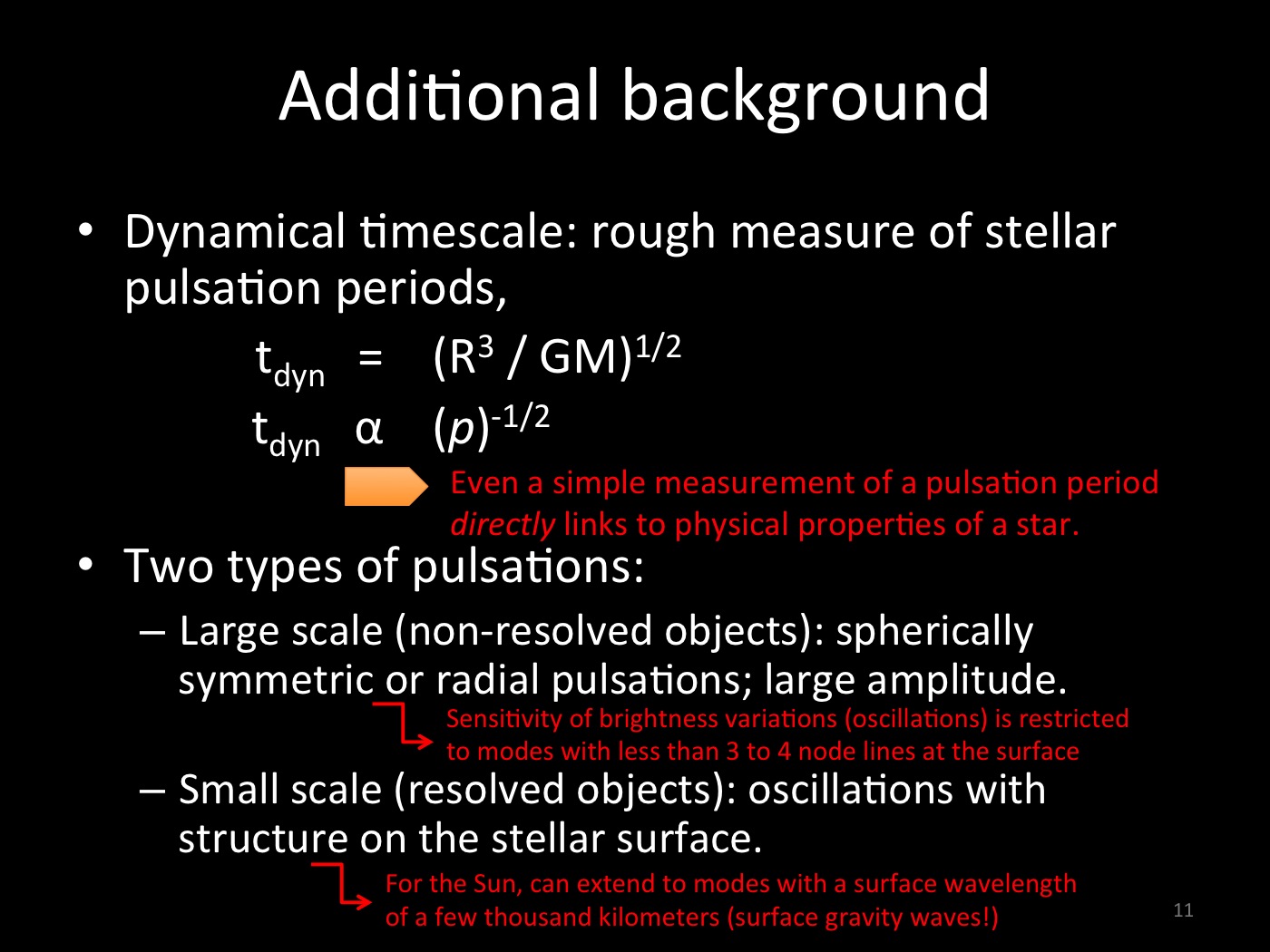

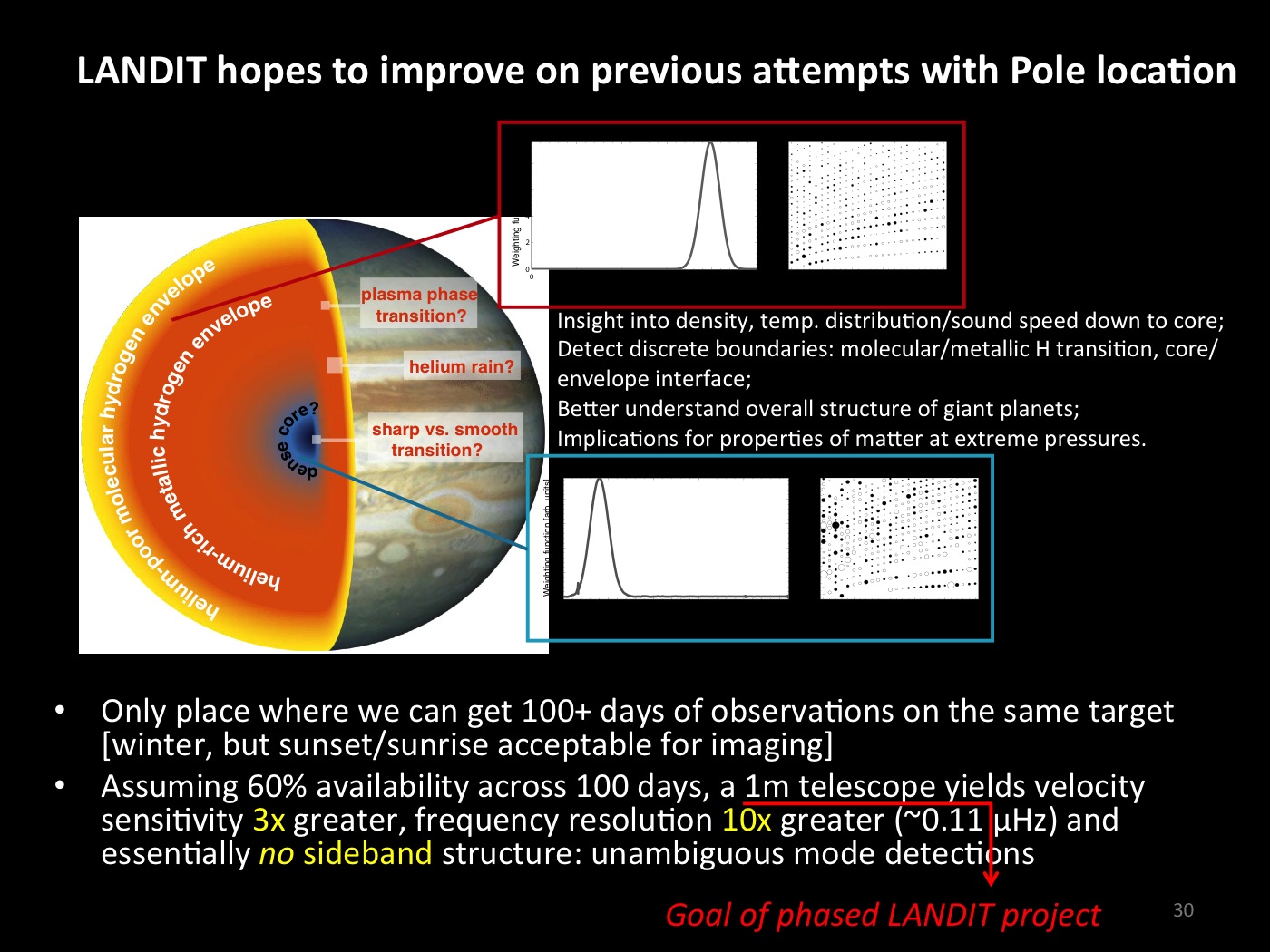

Link to Chapter 12: What is LANDIT, and why does it need the South Pole?

Link to Chapter 11: Work at the South Pole.

Link to Chapter 10: Thank you, friends.

Link to Chapter 9: At the bottom of the world

Link to Chapter 8: Onward, Southward!

Link to Chapter 7: Exploring McMurdo Station

Link to Chapter 6: Touchdown Antarctica

Link to Chapter 5: Flight Day!

Link to Chapter 4: ECWs

Link to Chapter 3: Christchurch!

Link to Chapter 2: Auckland

Link to Chapter 1: From Hawaii to Antarctica

Chapter eighteen is the last chapter in the tale of my Antarctic adventures for 2018. Like growing up, eighteen is where the story must take a different turn. For those of you that have followed along with me thus far, my sincere thanks. I hope you’ve found some entertainment, perspective and maybe even appreciation for the unique place that is the bottom of our world.

There are many more stories to tell, and one day I hope to tell them. I’ve learned a lot about myself here, and what I’m capable of. That knowledge, I hope, will carry into my next adventure.

In 2018, I was proud to be part of the United States Antarctic Program at South Pole. Being here is a Venn diagram of steadily smaller and more unique clubs: Antarctic scientists. National Science Foundation Principal Investigators. South Pole voyagers. I think this has been the most noteworthy achievement of my career to date, and I feel very blessed to have had this experience.

So without further ado… here is the last chapter, of the last leg of the journey. McMurdo, Antarctica, to Christchurch, New Zealand. And from there, tomorrow, back to the United States… and a new life.

Those of you that have been with me through the last 17 chapters already know about bag dragging the previous night, so I won’t go into the travails of my Sisyphus burden of well-used scientific equipment. The morning that I was scheduled to fly out dawned beautiful and sunny… and as an added bonus, Mt. Erebus was not only visible, but belching! Erebus is the volcano in whose shadow McMurdo Station sits… and belongs to a class of mountains known as “ultra mountains”; in fact, it’s the sixth-highest ultra on the planet, and the second-tallest peak in all of Antarctica. Not to mention being the southernmost volcano on the planet. Check out the “eruption”!

Then it was time to board ol’ Ivan the Terra Bus for the ride out to … wait, Phoenix airfield? If you’ve been following closely, you know that Phoenix airfield is where the wheeled aircraft land, like the C-17 that I came in on. The ski aircraft land at Willy Airfield. This late in the season, it’s too slushy out on the sea ice for the C-17s, so they have stopped flying. Which left only the LC-130s to ride back to New Zealand… right?

Nope! As luck would have it… we would be flying home with the Kiwis! We hitched a ride on a C-130 owned and operated by none other than the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF).

Why do I say luck?

A flight to the ice, to or from New Zealand, takes about five hours in a fast, jet-powered C-17. The propeller-driven C-130s, however, are much slower. The LC-130s, weighed down with heavy (and very unaerodynamic) skis, are slower still. Flying off the ice would be an 8.5 hour voyage in the USAF LC-130. The NZRAF C-130, however, flying without the burden of skis, could make the journey in only 7.5 hours. Doesn’t sound like much… but when you see the crowded accommodations onboard, I think you’ll agree that the hour makes a solid difference.

Interlocking, knee to knee, over fifty returning Antarctic explorers crammed into the C-130 for the ride home. The Herc is not a small plane, but when you’re shoulder to shoulder with two people, with your knees wedged between two other people, with no way to the bathroom except to climb over ten other people… well, it sure feels small.

The last view of Antarctica. Until we meet again.

And just like that, seven and a half hours later… we were off the ice, at the US Antarctic Program yard in Christchurch… back in civilization.

The RNZAF C-130 (left) and USAF LC-130 (right) at the US Antarctic Program Cargo Yard, Christchurch Airport

New Zealand Customs and Immigration: we were a strange-looking group to all the regular tourists, I bet.

Mixed feelings about leaving doesn’t even begin to cover it. I’m writing this post from the beautiful town of Christchurch, New Zealand, having just enjoyed my first (and most glorious) twenty minute shower in over two months. I went down to the galley — sorry, hotel restaurant — and ate lunch, and for the first time in a while, I knew no one around me. Growing up in Los Angeles, I’ve always enjoyed the anonymity of big city living. After living at the Pole, where I was able to recognize new arrivals with one quick glance across the galley, being around throngs of strangers is going to take some getting used to. Tomorrow, I get on a commercial flight (sigh, Jetstar again — don’t do it, kids. Just don’t do it) and start to make my way back to the US.

I’m left with a good feeling, though. A pleasant sense of exhaustion and accomplishment. Pride; in what I learned about myself and the Antarctic environment. Hope; that the data sitting on a terabyte drive in my luggage upstairs is useful and scientifically interesting. And, of course, wishing; that this time next year I have the chance to be back here again, outbound to the ice. LANDIT will be back at the South Pole in 2019. I can’t say for sure if I will as well, but I certainly hope so.

Thanks to everyone who followed along with me on this journey. It has been a once-in-a-lifetime experience, one that I will treasure for the rest of my life, and I’m glad some of you could be part of it with me. Until we meet again, Antarctica… or as we say back in Hawaii, much aloha and a hui hui kākou.

![All the future “Polies” at the Chalet [management building at Mac] for the briefing for the Pole flight! Flights change often, with no notice, depending on weather - not just at Pole, but other destinations on the continent. Sometimes one flight get…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57e3ffcfe58c62325710c18a/1542788896929-HEGYMII3HQKDC1GN67VI/IMG_5035+2.JPG)

![US Air Force C-130 Hercules, assigned to the US Antarctic Program from the New York Air National Guard, at the Christchurch USAP ramp. As of this writing [Nov 12], the first LC-130 (ski-equipped C-130) has yet to make it to the South Pole. The first…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57e3ffcfe58c62325710c18a/1542015695861-C9BOZXMIK735LP6M9XAL/unknown_5.jpg)