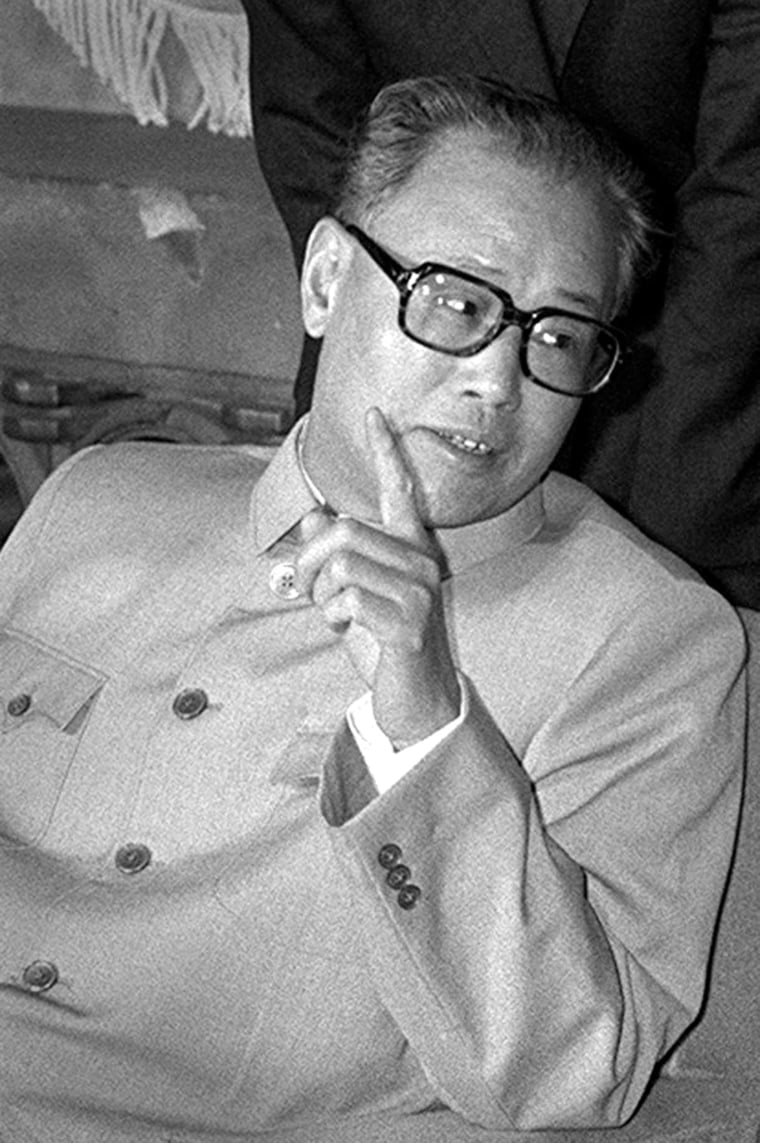

Zhao Ziyang, the former Communist Party leader who helped launch China’s economic boom but was ousted after sympathizing with the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protesters, died Monday in a Beijing hospital. He was 85.

The cause of death wasn’t immediately announced, but the official Xinhua News Agency said Zhao suffered from multiple ailments of the respiratory and cardiovascular system and died “after failing to respond to all emergency treatment.”

“He was very peaceful,” said Frank Lu, a Hong Kong-based Chinese human rights activist who said he had spoken to Zhao’s daughter Wang Yannan. “He was surrounded by all his family.”

Zhao had lived under house arrest for 15 years. A premature report of his death last week prompted the Chinese government to break its long silence about him and disclose that he had been hospitalized.

Zhao, a former premier and dapper, articulate protege of the late supreme leader Deng Xiaoping, helped to forge bold economic reforms in the 1980s that brought China new prosperity and flung open its doors to the outside world.

Fell out of favor

In the end, he fell out of favor with Deng and was purged on June 24, 1989, after the military crushed the student-led pro-democracy protests, killing hundreds and possibly thousands of people. Zhao was accused of “splitting the party” by supporting demonstrators who wanted a faster pace of democratic reform.

“The Chinese leadership owes him a lot,” said Yan Jiaqi, a former Zhao aide, in comments broadcast on Hong Kong Cable TV. “I hope to see the Beijing leadership formally express to the entire nation that Zhao Ziyang was the people’s good premier.”

The government took steps to minimize any public reaction to Zhao’s death.

The official announcement to China’s people was limited to a two-sentence Xinhua report carried on Web sites. It wasn’t on the midday state television news and CNN broadcasts to hotels and apartment complexes for foreigners were blacked out when they mentioned Zhao.

Police blocked reporters from entering the lane in central Beijing where Zhao had lived under guard in a walled villa. Ren Wanding, a veteran dissident, said police showed up outside his Beijing home late Monday morning and were preventing him from leaving.

Reports said Zhao occasionally traveled to the provinces. He sometimes was seen teeing off at Beijing golf courses or paying respects at the funerals of dead comrades, but otherwise remained hidden.

Usually seen in tailored Western suits, Zhao served as premier in 1980-1987, then took over as general secretary of the Communist Party, the most powerful post in China, under Deng, who remained paramount leader.

He helped initiate sweeping changes that invigorated an economy mired in the ruins of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution. Austere central planning gave way to material incentives and market forces that made China the world’s fastest-growing economy.

“He introduced capitalism to China,” said David Shambaugh, director of the China Policy Program at George Washington University. “Deng ... had instincts but not a lot of specific ideas about how to implement certain policies. Zhao gave specificity to those instincts.”

Those changes also brought inflation, income gaps between the rich and poor, corruption and other problems that Zhao would be blamed for when the conservatives drove him from power.

Clash with 'Red Guards'

Zhao’s 1989 downfall was not his first. Mao’s youthful “Red Guards” dragged him from his home in Guangzhou in 1967 and paraded him through the streets with a dunce cap before sending him off for years of internal exile.

The son of a landlord, he was born in 1919 in Henan Province. He joined the Communist Youth League in 1932 and became a full-fledged party member in 1938.

An agriculture expert in a country in which 80 percent of the people are rural, Zhao spent most of his career in regional government and party posts.

In the early 1950s, he directed a harsh purge in Guangdong province of cadres accused of corruption, ties to the Nationalists on Taiwan and opposition to land reform.

In 1957, he oversaw a rectification campaign in which 80,000 officials were sent to the countryside to live, work and receive criticism.

After four years in disgrace during the Cultural Revolution, he resurfaced in 1971 as a party secretary in Inner Mongolia. He won favor for his agricultural management there and in the southern province of Guangdong in 1971-75.

Zhao was named party secretary and governor of Sichuan, China’s most populous province, in 1975. With Sichuanese Deng’s backing, he dismantled the commune system, restored private plots and sidelined rural businesses, raised farm prices and revived bonuses for extra work.

His pragmatic policies there turned acute food shortages into bumper harvests. Between 1977 and 1980, Sichuan’s farm output went up 25 percent and industrial production rose 81 percent.

The “Sichuan Experience” became a model for the nation.

Zhao was known as a solid believer in the party. But he defined socialism much differently than Mao and other leftists.

“Of course we must keep to the socialist road. But what is socialism?” Zhao said in 1979. “The hallmark of socialism is the public ownership of the means of production, and the principle of socialism is ‘to each according to his work’.”

Deng brought Zhao to Beijing in 1980 as a vice premier and member of the party’s powerful Politburo.

Six months later, he was named premier, becoming a role model for the younger technocrats installed by Deng in key positions to carry out his ambitious modernization plans.

But the reforms’ expansion to urban areas sparked overheating of the economy in late 1984 and 1985, forcing Deng and Zhao to slow the pace of growth.

In November 1987, Zhao was named general secretary of the Communist Party following the ouster of Hu Yaobang, who was blamed for pro-democracy student unrest.

During the 1989 protests, Zhao called for compromise and expressed sympathy for some of their demands. But his adversaries, led by Premier Li Peng, overruled him, called in the military to quash the protests and used the turmoil to attack Zhao and his supporters.

Zhao was last seen in public on May 19, 1989, the day before martial law was declared in Beijing, when he made a tearful visit to Tiananmen Square to talk to student hunger strikers. He apologized to the students, saying “I have come too late.”

Little was known about Zhao’s personal life. A 40-minute-a-day jogger, he once revealed in an interview that he sometimes argued with his family at the dinner table and liked his grandchildren.

He was known to have been married twice and had four sons and a daughter. His second wife was Liang Boqi.