How I. M. Pei Shaped a Change-Resistant Paris

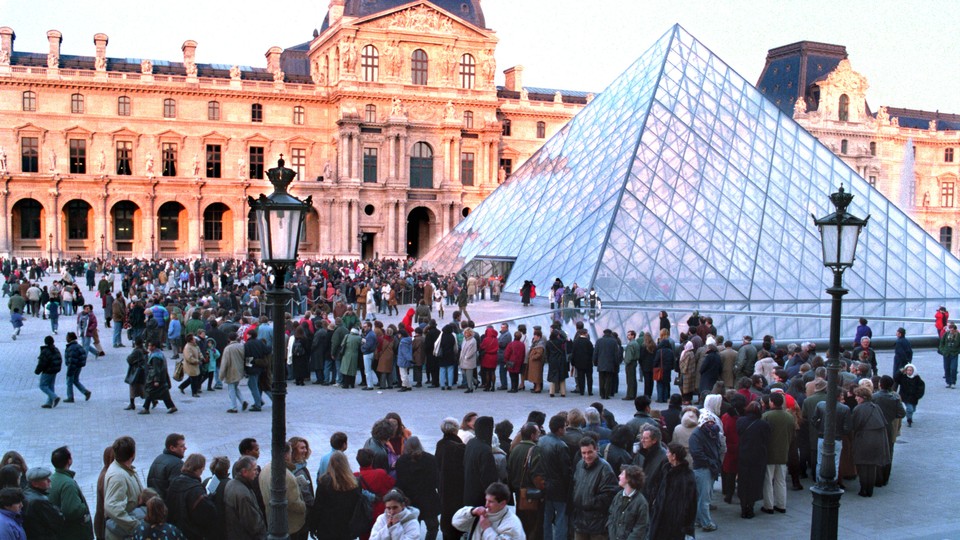

Parisians hated Pei’s pyramid when it first opened. It is now as synonymous with the Louvre as the Mona Lisa.

PARIS—Here in France, I. M. Pei, who died this week, is best known for one thing: The glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre Museum. When it opened in 1989, two centuries after the French Revolution, it was seen as a revolution of its own—and not necessarily a welcome one. Le Monde’s architecture critic at the time called the structure “a house of the dead” and said Pei was treating the courtyard of the Louvre “like an annex of Disneyland or bringing Luna Park back from the dead.”

Architecture is always political. President François Mitterrand, who wanted to leave his own mark on Paris, had chosen Pei for the project, without a competition, and he stood by the architect against the howls of protest. “The debate was very intense—you can even say ferocious,” Jean-Louis Cohen, an architectural historian at NYU and the Collège de France, told me. “It was perceived as the eruption of a foreign object—and what is more, an American object. It has to be seen also in the framework of France and anti-Americanism, which is sort of a permanent position.”

But over the years, the pyramid slowly came to grow on France, to the point that it’s now as synonymous with the Louvre as the Mona Lisa. Two years ago this month, President Emmanuel Macron, the youngest president in French history, had his inauguration in front of the Louvre. It sent a message that this was a president who embraced culture and who, with his nascent En Marche movement, was breaking with his Socialist predecessor the way Mitterrand, a Socialist president, had broken with his right-wing predecessors.

The controversy over Pei’s Louvre pyramid brings to mind a new debate that’s only now beginning to unfold in France, over how to renovate Notre-Dame cathedral after a catastrophic fire there last month destroyed the roof and spire. Should the cathedral be rebuilt exactly as it was, or should this be an opportunity to build something wild and new? A greenhouse on the roof? A Santiago Calatrava spine? The conversations have begun, even though the damage is still being assessed.

But the cathedral itself was a work of the imagination. In the 19th century, Viollet-le-Duc renovated it to recall medieval architecture. Many of the gargoyles date to that time. Its layering of architectural elements makes the Notre-Dame debate even more complex than the Louvre one. “Then you have an intellectual, even theological, discussion about what space is in the contemporary imagination and what historical state is meant to be re-created,” as Cohen put it. “Is it the elusive late-medieval condition,” or the era of Viollet-le-Duc, “who über-medievalized the church?”

As I wrote here, the pull between preservation and innovation is the central tension of Macron’s presidency—how to change a country resistant to change. Pei’s pyramid—at once solid and transparent, historic but timeless—shows that sometimes it can actually be done.