New York: Fake Masks

Whether what they make is “real" is of less concern to African carvers than to Western collectors, who value only the tribal art they deem authentic

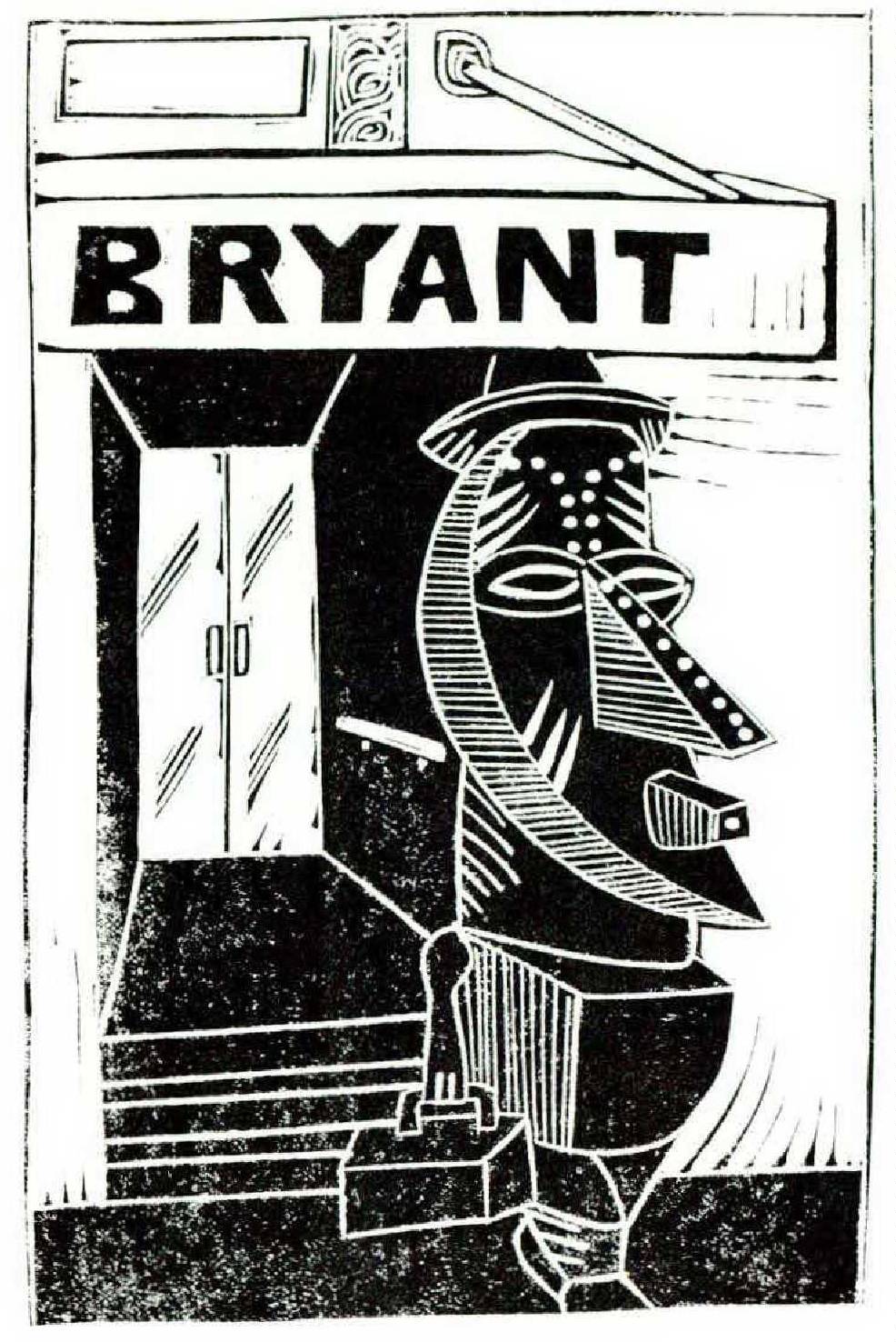

THERE ARE CERTAIN hotels just north of Times Square, in New York City, that draw a clientele made up substantially of African traders. Until it was converted to a welfare hotel, over the summer, the Bryant, at Fifty-fourth and Broadway, was the traders’ Ellis Island, the point of entry for the newest and poorest of them, where a room without a private bath cost only $150 a week. The beginning traders haven’t yet found a satisfying substitute for the Bryant, whose advantages in price and location far outweighed the disadvantage of its ambience—it was the kind of hotel where the clerk sat behind a sheet of bulletproof glass and signs posted in the lobby told the guests not to share needles or steal the light bulbs in the stairwell. The more established traders have moved to the next hotel up the ladder, the President, on Forty-eighth Street, which also draws some of the European student trade; and the most successful stay at establishments like the Woodward and the Wellington.

The best known of the African traders in New York these days are the street sellers, mostly Senegalese, who display watches and handbags on trays set up along Madison Avenue. But the real heart of the trading business—better established, more remunerative, and more prestigious than street selling—is African art objects. The Bryant in its day, and now the President, are full of African art dealers, known as runners.

Very few runners sell their wares out on the street, and then only in classy locations, such as in front of the Museum of Modern Art. Most of them deal privately, from their hotel rooms or on visits to galleries, museums, and the homes of collectors. A typical runner’s room will be crammed to the rafters with African art—art on the bed, art in the closet, art in a jumble of packing materials (plastic bags, old newspapers) piled on the floor. Somewhere there will be a space cleared for pictures of the family, back in Africa, and for a hot plate. A runner’s life is a spartan one, at least when he’s starting out; later, if he’s successful enough to establish a regular clientele of serious dealers and collectors, he can live a life on the road like that of a typical American traveling salesman.

The runners are not just a colorful sideshow to the world of serious African art. Aside from a trickle of work being sold off from European collections, almost all African art enters this country with them. Visits from runners are a daily event at even the very best African art galleries in New York, and the runners, after they’ve worked New York, usually go on the road in mini-vans, selling from hotel rooms in Chicago, Los Angeles, and other cities. All but a handful of the established American dealers in African art have given up on getting objects in Africa, partly because of laws there preventing the export of antiquities. The runners are their only source.

Most of what the runners offer for sale—by knowledgeable estimates, well over 90 percent—is fake, in the sense that it is made to look as if it had been used in traditional tribal religious ceremonies although it never really was. Faking is widespread in all areas of the art world, but it is far more so in African art than in any other kind. Fake African art supports not only the runners but also a substantial industry of carvers and merchants in Africa. In the United States it fills many low-budget collections and galleries, and also finds its way into the most prestigious museums, auction houses, and collections.

A FEW RITUAL OBJECTS were brought out of black Africa by European traders in the sixteenth century. In the colonial days of the nineteenth century, European explorers, missionaries, teachers, anthropologists, and administrators often brought home masks and figures from Africa. These usually wound up displayed in homes as curios, or in museums of ethnography. In the first decade of this century artists in Paris became interested in African ritual pieces, first for their visual appeal and then for their genuine artistic greatness. If one event put African art on the map, it was Picasso’s famous epiphany during a visit to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1907. He said afterward, according to his mistress, “At that moment I realized that this was what painting was all about.”

At the time, Picasso was working on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which is considered the watershed painting of modern art. The prevailing theory (denied by Picasso during his lifetime) is that after his visit to the Trocadéro he repainted the faces of the two right-hand figures in Les Demoiselles to make them resemble African masks.

That African art, which at the turn of the century had been considered lowly and backward, should have provided the avenue for this epochal artistic advance shows what tremendous changes were then taking place in the upper reaches of Western culture. Other artists besides Picasso began to feel that European bourgeois society, which considered itself superior to ail others, had actually become mannered and tame—and so had its art. African religious carving, with its aura of magical power, offered a clue to how art could return to the deep channels: artists, by looking backward to “primitive” cultures for guidance, could lead all of Western culture forward into a new profundity. Art would become more symbolic than representational, and the artist could begin to think of himself as the possessor of supernatural powers. African carvers, of course, did not regard themselves with such grandeur or Western society with such contempt. Their self-conception was roughly like that of medieval artists: they were servants of the Supreme Being and of his high priests on earth. But in the West, African art helped lead to a completely different and much more exalted conception of artists, in which art replaced religion (to some minds, at least) as the link between mankind and the ineffable.

Soon the international avant-garde began collecting African art. In 1914 Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery, 291, in New York, mounted the first American exhibition of African art as art. In 1935 the Museum of Modern Art presented a major African art show. After the Second World War a true market in African art gradually became established in the United States. In the 1950s African masks became one of the standard accoutrements of the sophisticated living room, and this taste, like most, gradually spread from an oddly hybrid group of cultural trendsetters (beatniks, professors, Rockefellers) to a wider group. The Peace Corps, the civil-rights movement, African nationalism. and the beginning of mass tourism to West Africa all increased American interest in African art. Interior decorators began putting African art in the homes of their meat-and-potatoes clients.

In 1966 the Parke-Bernet auction house in New York established, for the first time, a firm price level for highquality African art when it sold off one of the leading collections, that of Helena Rubinstein, and top pieces went for more than $25,000. In 1974 a major New York gallery, the Pace, established a primitive-art department and began to put on major shows of African art, with opening-night parties and slick catalogues. Prices skyrocketed during the seventies; auctions and galleries proliferated; doctors, lawyers, and stockbrokers began to collect for investment purposes. The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its Michael C. Rockefeller wing, a lavish home for African and Oceanic art, in 1982. Prom 1982 to 1986 the market softened, but lately it has been picking up again. The finest pieces fetch well over $100,000. The African art market is bigger by far than the market for any other kind of primitive art.

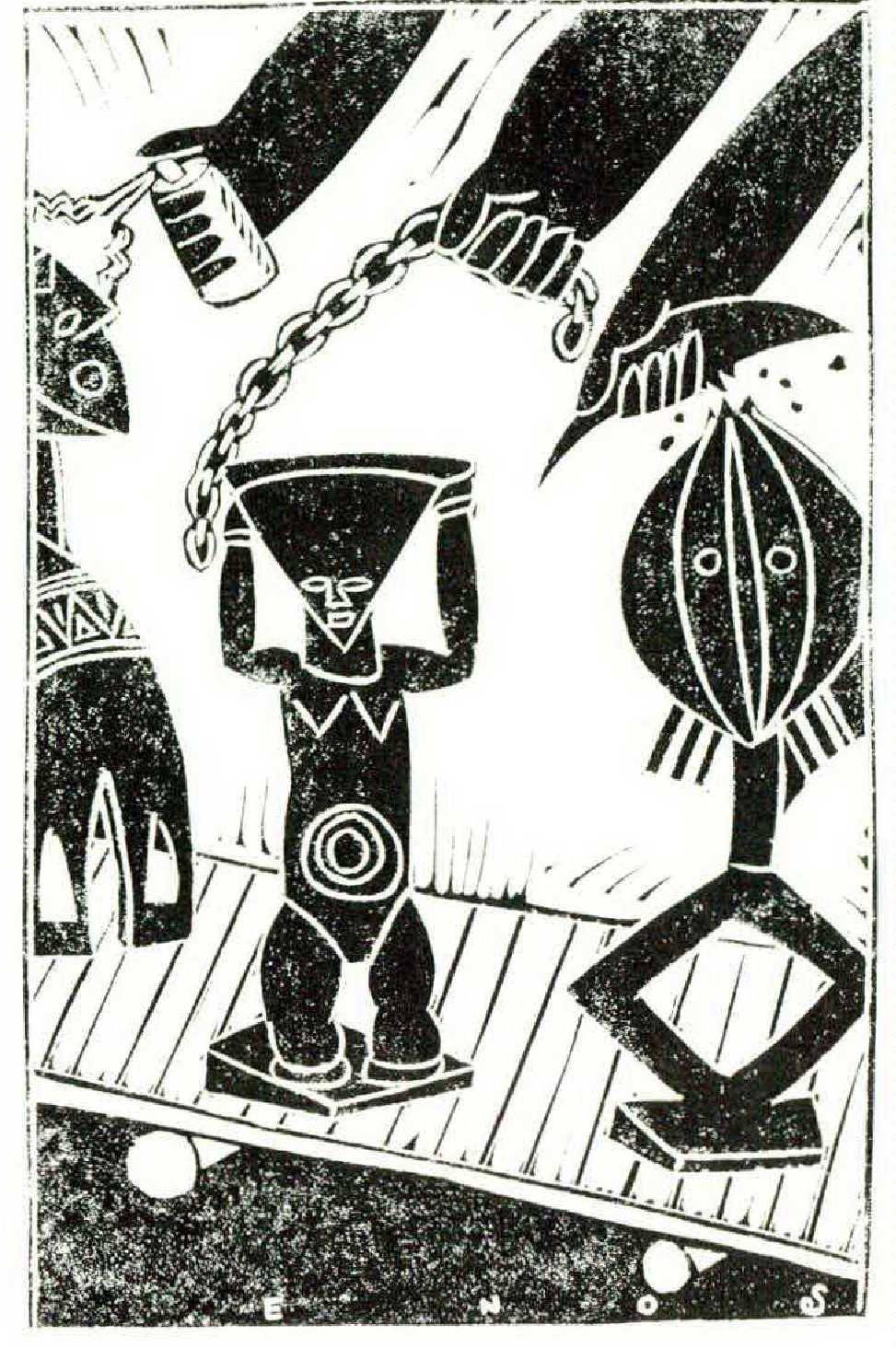

As the market developed, so did a strong consensus about what constitutes a valuable piece of African art. It must be hand-carved by a tribal carver who uses traditional tools (mainly an adze), works for a traditional patron, and intends the piece to be used for a traditional purpose connected with a native ritual. Then the piece must actually be used—dealers speak of a piece having been “danced”—preferably over a number of years. The traditional religious process is supposed to ensure that the piece will be imbued with primal spirituality of the kind that Picasso discerned in African art in the first place.

WITH THE ELEGANT simplicity of a supply-and-demand graph, the conditions under which valuable African art is produced have steadily eroded during the time that the Western market for it has grown. Modernization, national independence, and widespread conversion to Islam and Christianity have all meant that the agrarian tribe practicing an animist religion is losing its hold as Africa’s basic social unit. Expert opinion about the likelihood that more African masterpieces will be produced is gloomy. The scholar Werner Gillon, in the concluding paragraph of A Short History of African Art, writes, “The consequent decline and, indeed, almost total demise of artistic creation linked to the old social order came more swiftly than even the most knowledgeable observers could have anticipated.”

In Africa the carving of nontraditional pieces for Westerners by traditional carvers had been going on long before the runners opened up a major art trade in the United States. In the 1500s carvers of the Benin and Sherbro tribes made ivory pieces on commission for Portuguese patrons, using the native style but European imagery. The widespread commissioning of works in wood by outsiders— either Europeans or African traders—can be shown to have been going on for at least fifty years and probably has been for much longer. The Makonde tribe, of Tanzania, developed an entirely new style of carving for the tourist market.

If it seems shocking that African carvers would be willing to do their holy work for money, that’s partly because we’ve imposed the aura of the modern artist on them, even while insisting that their greatness comes from working in a pre-modern society. The African pieces that we see in museums—smooth, austere dark wood caught in a spotlight— were treated much less lovingly back in Africa. Tribal religious carvers try to make pieces so good that they will be inhabited by spirits, but carving is only one part of the process by which a piece attains “vital force”—it may also be prayed and danced over, sprinkled with powders, and bathed in sacrificial blood. When in ritual use, pieces are often painted in loud colors, festooned with bits of cloth and twine, and incorporated into garish costumes. Since the piece itself is considered neither a work of art nor an embodiment of a deity but only a temporary residence for the vital force, pieces that are priceless treasures here were often simply discarded after a time there. Secular carying isn’t necessarily sacrilegious, and after a tribe converts from animist religions, its carvers see no reason to stop carving, especially if they realize that it can be the tribe’s main source of cash.

African art is extremely fertile ground for fakery. It has the basic condition for all art fakery—demand that far outstrips supply—and also, from the standpoint of a faker, several more particular advantages. African art is anonymous; through assiduous effort scholars have been able to take educated guesses about the identities of a few great carvers, but for the most part nobody knows who made the best pieces. It is generic; every Ashanti fertility doll, for example, has a flat circular face with the features arranged in a certain way, so an exact copy of a famous piece isn’t necessarily inauthentic. It is impossible to establish provenance; almost never does an owner know exactly how a piece passed from the carver’s hands into his. In fact, if the piece is a recent export, the owner had better not know, because he is violating a UNESCO convention. The great majority of pieces on the market are made of wood, and so aren’t more than a hundred years old (if thev were, they would have rotted back in Africa) and can’t be scientifically dated. Finally, a large group of highly skilled fakers is available—namely, the very same African tribal carvers who made the “real" pieces.

The African art establishment’s first line of defense against the threat that faking poses to its legitimacy is the idea that there is an unmistakable difference between the fake and the real. Since the Second World War, Africa, like other primitive-art-producing areas, has had factory-like operations in its cities that turn out thousands of pieces of what is called tourist art or airport art—cheap copies of tribal pieces, sold in local markets, with no pretensions to authenticity. Experts are completely dismissive of the quality of tourist art and insist that no one could confuse a tourist piece with a real one. They think that the work of African carvers done in response to the commercial demands of modern society is inevitably banal. Also, at least since the twenties European forgers have been producing fake African art, but this is usually portrayed as an extremely small industry, producing a few top-of-the-line fakes intended to fool the upper end of the market. Anyway, a real expert could tell the difference. Before the 1970s the idea that all art coming out of Africa had to be watched carefully because it might be fake was not widespread in the African-art world.

WHEN THE AFRICAN runners started coming to New York, in the early sixties, their wares were not automatically suspect. The first runners, according to knowledgeable people in the African-art world, were members of turn Islamic extended families from Gambia, a tiny nation on the West African coast. They set up shop in the Hotel Lucerne, at Seventy-ninth and Amsterdam Avenue, on the Upper West Side, and began making their presence known to gallery owners, museum curators, and collectors. To the runners, the interest of Americans in African art was inexplicable and the neat typology of real, fake, and tourist meant nothing. Their hotel rooms would be packed with material that ranged from worthless to extremely valuable, all mixed together and all priced very low. “You had to go to a dimly lit room at the Lucerne and look at hundreds of pieces,”says Ernst Anspach, a veteran collector in New York. “You looked at a dismaying array of objects, some very good, and the price was the same for good stuff as for bad.”

The history of the runners is an oral one, and therefore not strictly verifiable. It holds that in the 1960s, after the Gambians had established their business, another group of traders came to New York: members of the Hausa, a tribe originally from northern Nigeria which for hundreds of years has made its living trading everything from ivory to textiles to slaves. The Lucerne filled up, and the runners became a substantial presence at two other hotels on the West Side. A Hausa trader might fly to New York with a load of art (often smuggled out of Africa along old gem-running routes), rent a van, work his way across the country, end up cash-rich and artpoor in Los Angeles, fly to Hong Kong, buy a load of watches, and fly back to Lagos to sell them and pick up more art. Those were the wild frontier days of running. Novice collectors sometimes bought by the roomful. Anspach once got a call from the Met asking him to check out a runner who had come over with 2,300 pieces and rented warehouse space for them in the expectation of a rapid sale, with the museum as his primary customer.

Eventually, the runners—who are mostly from Guinea, Liberia, and Camcroon these days—moved down to the Times Square area, a good place to buy cosmetics and cheap Japanese electronic goods for resale back home. By now they have learned what the American market values and what it doesn’t, and their prices for good pieces have gone from under $100 to over $1,000. Still, most of the top Americans in the field continue to see runners, because they are the only source of material besides existing collections and African tribes themselves. Greenhorns patronize the runners too, convinced that these people—usually illiterate and speaking only broken English—can’t possibly know what the stuff they’re selling is really worth.

Because I found that it was impossible to gain access to the runners as a reporter, I began buying art from them earlier this year. I found them to be nice, incredibly persistent (they call me all the time), and honest to the extent that if you ask them no questions, they’ll tell you no lies. They don’t claim a magnificent tribal origin for most of what they sell, but if pressed about the age of a piece, they’ll usually say, “Oh, it’s thirty, forty years old.” Michael Oliver, a New York dealer I trust, because of his long experience with runners in Africa and in the United States, examined a couple of masks I bought on this assurance and said that one, two years old would be more like it. On one mask, if you looked inside a crack you saw that the wood was green; on the other, the patina of age came right off with the application of a little acetone on a Q-tip, again revealing green wood.

AVERITABLE AVALANCHE of African art has entered this country with the runners over the past twenty years. By all accounts only a tiny fraction of it is real. It’s doubtful that any of it is European-made fakes, and no more than a substantial minority is true tourist art. The majority is produced by a growing industry in Africa and bought by Americans, quite often including serious collectors.

Probably most fake African art in this country ends up being sold in stores that aren’t quite art galleries—they’re gift shops, or home-décor shops, or import stores. Their price range is in the low-tomiddle three figures, and the claims the shops make for what they sell vary widely but generally fall short of the reverent genealogies that serious galleries give for their pieces. One of the runners I met in the Hotel President, for example, was busy affixing his goods with the price stickers of a crafts shop in Lexington, Kentucky. If you shop in stores of these kinds, you should believe no claim grander than that the pieces were handcarved in Africa within the past five years. They have no resale or investment value, though some of them are quite attractive.

The galleries and dealers selling African art that supposedly is invested with tribal spirituality and of lasting value have, on the whole, a spotty record and should be approached with extreme care. Some dealers are simply dishonest, and knowingly present fake art as real. A larger group put the most optimistic assessment possible on pieces they buy from runners, and they’re frequently wrong. When I asked top-of-the-line collectors, dealers, and curators how many African-art dealers in the world can be trusted absolutely not to sell a fake, the estimates I got ranged from a high of twenty to a low of five, and this is out of hundreds of dealers. Pace, Michael Oliver, and Merton Simpson, for example, all in New York, are said to have unblemished records concerning the authenticity of what they sell.

Anyone can spot a crude fake, by applying acetone to the patina (this shouldn’t bother the dealer, because a real patina won’t come off). But it requires a real expert to detect a skillful job. Some dealers say they can simplv look at a piece and feel the spirituality. Only a few scholars in the world, though, are so well versed in every tribe’s iconography, carving techniques, and rituals that they can reliably spot telltale errors, such as incorrectly placed signs of wear or decorative motifs. Since the fakers usually work from photographs, they sometimes make mistakes in perspective or in the size of a piece (they know that the bigger the piece, the more it is worth in America). Roy Sieber, a professor at Indiana University and the associate director of the Smithsonian Institution’s new National Museum of African Art, has used x-rays to expose the use of nontraditional tools and materials like metal-cutters and screws. So far, though, the best fakers have been able to stay one step ahead of the detection abilities of most potential buyers.

Often it’s their very success that exposes them—suddenly there will be too many identical versions of an important piece around. But when that happens, they’ll move on to something else. African Arts, published by the African Studies Center at UCLA, is the leading English-language magazine in the field and the prime advertising medium for galleries. In 1976 it published a special issue on faking in which several of the contributors (one a consulting editor of the magazine) casually mentioned that African Arts itself regularly publishes advertisements from dealers featuring pictures of fake objects.

Experts say they often spot fakes in the catalogues of the leading auction houses, and the houses have withdrawn pieces from auction because they have been found to be fake in the time since the catalogue was published. (It’s easy to determine that a piece isn’t real from a photograph if its iconography is incorrect, though to prove that a piece is real should require a firsthand inspection.) In a notorious example, Sotheby’s in 1981 had to withdraw a mask that had appeared on the cover of one of its auccion catalogues. The cover of a book called Collecting African Art showed a carved wooden pipe in the shape of a man; the metal stem was found to be a later addition. In an auction last spring Phillips sold a pair of pieces billed as Yoruba bronze-amulet fragments from eighteenth-century Nigeria. The figure on the pieces is female, though, whereas every known authentic example from that tribe and date depicts a male king. A Parisian auction house dealt with the authenticity problem this year by printing in its catalogue the disclaimer that “these objects have never been used in any rite or sacred dance"; as a consequence, the prices fetched were low.

It’s not unheard of for fakes to be shown in major museum shows. “Perspectives: Angles on African Art,” a show assembled by the Center for African Art, includes objects that prominent people interested in African art have chosen as being among their personal favorites. One of the selectors, David Rockefeller, picked a Fanti figure from the collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art which is apparently a fake, and the book accompanying the exhibit, published by the Center for African Art and Harry N. Abrams, contains a disclaimer stating that the authenticity of the piece “has been challenged.”

The donation of fakes to museums by collectors is so widespread that the Internal Revenue Service’s Art Advisory Panel in 1984 established a special unit to review the deductions claimed on donations of primitive art. In 1985 it reviewed the valuations claimed by taxpayers on 595 items and adjusted 397 of them downward; the average overvaluation per piece was 571 percent (in 1984 it was 1,959 percent). In the one primitive-art case the Art Advisory Panel has brought to court so far, an Oklahoma couple named Ralph and Virginia Neely gave 318 pieces to the Duke University Museum, which exhibited fifty-seven of them. Most were fakes. They also gave 112 pieces to the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, in San Francisco, whose top African-art authority, Thomas K. Seligman, is a leading expert in the field. Seligman accepted all the pieces, and the museum sold 110 of them for an average price of $238—less than a tenth of the value the Neelys had claimed for their donation on their tax return.

People familiar with this side of the African-art world say that most collectors who try to give away or put up for auction large numbers of fakes believe that they are real; usually the collectors were gulled by dealers. Perhaps the most infamous dealer of all, a man who lives up to the legendary standard of chutzpah established by the character Zero Mostel played in The Producers, is a Frenchman named Henri Kamer. Kamer made his first trip to Africa in 1947, and all through the fifties he brought out many valuable real pieces. Then he opened a string of galleries—in Cannes, Paris, New York, and Palm Beach—and became known as a leading spotter of fakes. He wrote about techniques for authenticating African art, and was Sotheby’s hired expert at the Helena Rubinstein auction. He was also known for his grand way of life: he owned two Rolls-Royces, and in New York he kept an apartment in Aristotle Onassis’s Olympic Tower. Some of the leading workshops are clustered around Korhogo, the Ivory Coast (specializing in Senufo birds); Kumasi, Ghana (Ashanti fertility dolls); Bamako, Mali (Bambana antelope headdresses); Monrovia, Liberia (Dan masks and figures); and Foumban, Cameroon (Bamileke masks). Nigeria, Zaire, and Upper Volta are also full of workshops. The most common buyers of their work are traders from the Hausa and Fulani tribes, who typically will take it to a warehouse in town to await resale either to runners bound for America or Europe or to dealers in big African port cities that are considered major art markets, like Abidjan, the Ivory Coast, and Kinshasa, Zaire. There can be no doubt that this work is fake under the standard definition—that it must be “intended to deceive.” Since traders and runners know that Westerners know that most of the tribal cultures have been dead for decades, they try to make the pieces look old. Often the workshop itself will take on aging a piece. The most common methods include darkening the piece with vegetable dyes or shoe polish, rubbing dirt into it, “distressing” it, which means banging it with blunt objects, rubbing it with another piece of wood, leaving it out on a termite heap for a couple of days, and breaking off and then reattaching a section (evidence of “native repair” is highly prized by collectors). Sometimes the traders will age pieces in their own facilities in town, or, in an effort to achieve what economists call “vertical integration,” they will induce the carvers to move into their own compounds.

He was the main dealer involved in building one of the great private collections, that of Paul Tishman, the New York construction magnate. When the Tishman collection was first exhibited, at the Musee de l’Homme, in Paris, it was found to contain many fakes, which were later removed from the collection. (Kamer says that “two or three pieces” in the collection were “not good,” and adds, “Everybody makes mistakes, even the biggest expert. Three out of five hundred pieces isn’t bad, considering that he sold the collection for four times what he paid for it.”) Tishman sued Kamer and won a judgment, which Kamer never paid. Kamer mostly got out of the African-art business, but he later sold fake antiquities to a major New York gallery. In 1982 he was successfully sued by the Irving Trust company for withdrawing $1.4 million that the bank had erroneously deposited in his account and putting it in a numbered account in a bank in Monaco. Today he lives in New York and Key West, and is the executive vice president of Historic Treasure Management, a company that looks for buried treasure.

THE WORKSHOPS THAT have sprung up in Africa over the past fifteen years are far more sophisticated than the urban factories that produce tourist art. The piecemeal accounts from dealers, curators, and anthropologists make clear that the best workshops are located in villages near back-country cities; that the half dozen or so carvers in each workshop are members of traditional artproducing tribes, and often descendants of animist carvers; and that they always carve by hand, usually with traditional tools, and produce some pieces quickly and others with great care.

The workshops carefully keep up with market trends in New York, Paris, and London. People who have visited them say they have seen the latest coffee-table books and auction catalogues of African art in workshops deep in the bush, and when the workshops branch out to the styles of other tribes, they choose those that are in vogue in the West. Skilled fakes of the latest favored styles now come on the market with astonishing rapidity; runners turn up with copies of the material within a matter of months. In the 1970s the New York market was flooded with tourist and fake Dan masks and Bambana antelopes, and minor price collapses ensued. Knowing that if a piece has been danced it will be more valuable in New York, some tribes that practice a hybrid of Islam and animism will oblige by adjusting their rituals—by, for example, using many more masks than is customary, or by using ritual dances to celebrate nontraditional holidays, for example Cameroonian National Day. Traders and dealers will sometimes photograph these rituals; in any case, they can claim with a straight face that a piece they’re selling was danced.

The two most complete recent firsthand accounts of the operations of workshops come from Dolores Richter, who traveled to Africa while a graduate student at Southern Illinois University, and Doran H. Ross, the curator of the African collection at UCLA’s Museum of Cultural History, and his colleague Raphael X. Reichert. Richter lived for more than a year in the northern Ivory Coast with the Kulebele, a wood-carving subgroup of the Senufo tribe. She concluded that carving for money has actually enhanced the carvers’ artistic skill, because it allows them to devote so much time to their craft; previously they carved only when new pieces wore needed for rituals. The Kulebele continue to carve ritual pieces for the Senufo and for other tribes while also carving for the market. They observe old tribal customs (for example, the practice of sinking an adze into anyone who watches them carving), at least in part to keep competitors out of the business. Their best commercial work is widely admired within the tribe, for aesthetic reasons and because it has brought the carvers motorbikes and television sets—and watches, which are prized even though the Kulebele don’t know how to read them.

In 1977 Ross and Herbert M. Cole put together an exhibition. The Arts of Ghana, and wrote an accompanying book with the same title. They later discovered that the exhibition had included five fakes, lent by private collections and museums. In 1979 Ross and Reichert persuaded a trader in Accra, the capital of Ghana, to take them to the workshop in Kumasi where the fakes had been made. There they met three carvers, relatives of the head Ashanti carver, who had been been educated by Roman Catholics and had been in the business of faking for about six years. The carvers worked mostly in the Ashanti style, though they had produced Fanti and Baule work, too. To make their pieces look old, they patinated them with, among other substances, black automobile enamel, a mixture of carpenter’s glue and soot, and the juice of kola nuts, and they sold them to Hausa traders. Like the Kulebele, they were frank about being in it for the money, but they also took great pride in their best work. In a 1983 article Ross and Reichert wrote that at least twenty of the workshop’s pieces had been presented as authentic in the previous six years; since then, Ross says, he has seen pieces on display in eight museums, which he declines to name because of “legal implications.”

THE USUAL KNOCK on contemporary African carvers is that the influence of the West has caused them to devolve into merely folk artists. Critics can hold up a traditional Yoruba Gelede mask side by side with a modern version that has a motorcycle cop perched on its head and say that here is evidence of a culture that has lost its serene self-confldence and come to think of itself as simple and goofy.

The best workshops, though, know better than to let any folkish note creep into their carvings. They might be compared to European court artists: they work on orders from and in styles dictated by their patrons, but their talent is so great that it’s unfair to deny them the title of artist just because they’re not trying to express a personal vision. The difference between the carvers and the court painters is that the carvers live thousands of miles from their patrons and have never met them. Still, the work they do is dictated by the tastes of Paris and New York. It’s imbued with the assumptions of the court (in this case mainly the assumption that the African genius is a primitive tribal one) just as surely as Goya’s work was, and the degree of secret disdain of the patron by the artist is probably similar.

For the moment and likely for the future, there is no chance that the Western market could appreciate the African workshops for what they really are. All the evidence suggests that that’s fine with the workshops. They’ll just keep carving, and the market in African art will continue to be made up mostly of fakes.

—Nicholas Lemann