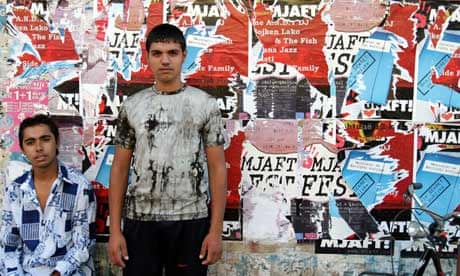

No one will ever know how it all started, and in a way the original disagreement no longer matters, now that blood has been shed. But there is still Ismet (not his real name). Ismet will soon be 16, which is a problem. Becoming an adult means he must shoulder the burden of the family legacy and answer for it. He looks unconcerned as he approaches the school gate in a village a few kilometres outside Shkodër, the main town in north-west Albania. But before starting his story, he walks down the road, out of sight of the other pupils.

Ismet looks down as he talks. "I'm not sure what to say. I'm being blamed for something I didn't do," he starts. His problems are due to his father. In July 2001 the latter became involved in a dispute with two brothers in a neighbouring village, a confusing tale of land on which his father allegedly encroached.

There had not been any previous disputes between the two families, but insults and threats degenerated into violence. After killing the two brothers, Ismet's father went into hiding in the mountains for two years. Tried in his absence, he was sentenced to life imprisonment and subsequently arrested. The justice of the state had had its say, but not private justice. For the past 10 years the family of the two murdered brothers has been demanding vengeance.

Albania, which hopes to make its application for membership of the EU official this year, has made a radical break with its communist past. But blood feuds, one of its most deep-rooted customs, are still very much alive, demanding an eye for an eye in an endless spiral of grief. Just an insult or some breach in marital morals may justify bloodshed. The ancestral code of Kanun, which has governed rural life in Albania for five centuries, still holds sway, particularly in the mountainous north.

This complex system of customary laws once governed every aspect of life: inheritance, trade, marriage and crimes. "The Kanun has survived for so long because it is a way of preserving cultural and legal identity," says the writer Besnik Mustafaj. In the capital Tirana the anthropologist Nebi Bardoshi describes it as "a form of opposition to any form of state law, not just Ottoman law" – the country having gained its independence in 1912, after four centuries of Ottoman rule. "The Kanun is linked to the religion of blood, of which feuding is just one aspect," he adds. "The law is based on two pillars: fair treatment between men and reciprocity."

This system did not provide for endless escalation. On the contrary, from the outset it left room for mediation, through the council of the elders. A promise of safety (besa) could be granted to some members of a clan. But tradition has withered away and all that remains is the idea of vengeance. "After the murder," says Ismet's grandfather, Kalter, "I went to the home of the two brothers twice. I told them there was no problem between us and their family. I tried to negotiate but they would not even sit down, as required by custom."

Kalter welcomes us to the family home where he lives with his wife and Ina, Ismet's mother. The house is small but well kept. "Ismet will be 16 next January and he should be starting at the high school in another village," Ina explains. "I don't want to take that risk. We want to send him abroad."

Everything has changed in Albania since the end of the communist regime. Organised crime has taken hold and human trafficking has flourished thanks to arranged marriages, giving rise to more family strife. Above all many violent disputes have focused on land ownership. Despite the relatively small size of the country the government's authority has been severely challenged. In 1997 the Lottery uprising, a conflict verging on civil war, erupted following the collapse of various financial pyramid schemes. In the ensuing chaos arms dumps were ransacked, the arms boosting the old patriarchal system. With no effective law enforcement, families resorted to the Kanun.

Albanian's penal code refers to vendetta as premeditated murder, but the courts are still at a loss to know how to cope with this parallel system of justice. "Families feel entitled to take vengeance," says Përparim Kulluri, the public prosecutor in Shkodër. "We've seen cases where the relations of a victim have given testimony clearing the accused, so that they can settle the score themselves."

In 2006 Liliana Luani, a schoolteacher in the city, started an NGO to look after children suffering from the consequences of the Kanun. With increasing numbers leaving the land to look for work in the towns, many young people belong to families embroiled in feuds. Luani knows of 120 cases in and around Shkodër. Her organisation provides tutoring so the children can study at home.

Theoretically under Kanun rules children cannot be touched. "But the old rules have disappeared since the fall of communism," Luani says. "Old conflicts have resurfaced, new ones have started, mainly linked to land ownership rights. There was a case in Shkodër where a man tried to kill a three-year-old."

According to the National Reconciliation Committee some 1,650 families are living in isolation, locked up inside their homes. "The figure is up by 200 on 2010 and 2009, because of families returning to Albania after failing to obtain asylum in a western country," says the chair of the committee, Gjin Marku.

It is very difficult to find any firm statistics to gauge the scale of the problem. In a report in February 2010 the UN Human Rights Council estimated the number of feuds had significantly dropped over the previous five years, but admitted that official statistics were incomplete. The committee says settling of scores caused 95 deaths in 2010, 75 in 2009 and 9,870 since 1990. The prime minister, Sali Berisha, sees things differently. A native of Tropojë, he thinks the Kanun has its merits. "It acted as a very powerful deterrent imposing incredible self-control. There are very few instances of such feuding, proof that the law of the state prevails," Berisha says. "When I entered the government [in 2005] there were 1,800 people in prison; now there are 5,000."

Such figures are probably misleading. NGOs, assisted by village elders, are the only bodies making any effort to mediate disputes. Reconciliation between two families is a complex process, subject to strict rules, which may take years.

The higher you go up into the mountains, the further back into the past you travel. The more the spirit of vengeance contaminates the next generation, the more the Kanun loses its original meaning.

This article originally appeared in Le Monde