Zhao Ziyang and Yin Haiguang: A common vision, a common fate

This year marks the anniversary of many historical events, yet the 100th birth anniversaries of two people were all but forgotten.

These two people found themselves on opposite sides of the Taiwan Strait after 1949. Their paths were separate, but their thinking - and their ends - were similar. Looking at their lives in the context of China's history, one laments the insignificance of individuals; so much so that they can be silently obliterated.

Zhao Ziyang - The idealist

Zhao Ziyang was born to landowners in Hua County, Henan. As a child, his teachers encouraged him to join the Communist Youth League, which saw him distributing crops from his family's fields to farmers. During China's war against Japan, he ran the Communist Party branch as well as land and farmer movements in his hometown with great success, gaining recognition from party leaders including Deng Xiaoping. For the first few years following the war, he continued to achieve results in land reform, securing his position in the party as the expert on land and economics issues.

After the war ended, Zhao was posted south to Guangdong, to assist Guangdong Provincial Committee secretary Tao Zhu in land reform work. However, he had run-ins with local Guangdong leaders such as Ye Jianying, and it was not until Mao Zedong gave instructions for Ye Jianying to be transferred away and for Zhao's cadres to take command that they were able to push through the policies of the central government.

However, it is on record that in carrying out their land reform and cooperation movement, Tao and Zhao became uncomfortable and concerned with the wrongful political convictions fabricated by the far-left movement, and started to feel more inclined towards the gentler approach of politicians such as Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.

Zhao had a strong grasp of public sentiment and was very close to the people of Guangdong. He implemented many policies that improved productivity. During the Great Famine, he managed to stabilise Guangdong's economy, and did not take a tough stance against the wave of Chinese emigrants to Hong Kong. During the Cultural Revolution, Tao Zhu lost his power and Zhao was sent to take on manual farming work for a few years before being transferred to Sichuan to save the failing economy.

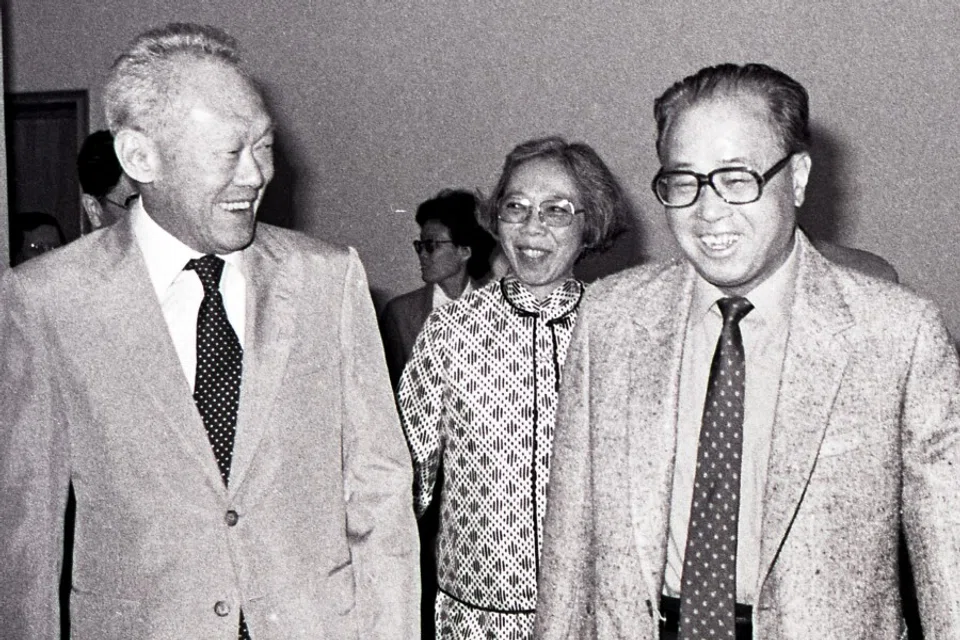

When the Cultural Revolution ended, Deng Xiaoping came back and brought Zhao Ziyang to prominence, and Zhao's outstanding work in Sichuan was made known to the whole nation. In the 1980s, at the peak of China's reform and opening up, Deng Xiaoping, probably knowing that he could not straighten out the country on his own, continued to keep a tight hold on military power, while giving political rein to General Secretary Hu Yaobang and relying on Zhao's marketisation approach in terms of the economy.

During this period, Zhao Ziyang totally abandoned the concept of a planned economy, setting the foundation of China's subsequent economic marketisation and privatisation. In his nine years as Chinese Premier and Party General Secretary, Zhao not only reversed the disasters caused by the Cultural Revolution and the far left, unleashed the Chinese people's ability to grow the economy and improve their lives, and implemented administrative reforms, but he also actively led China in connecting with the world.

Zhao faced the Tiananmen incident after he took over, and was no match for the blowback from the conservatives. He was placed under house arrest until his death.

In particular, the intellectuals appreciated how he wanted to create an atmosphere of openness and freedom in speech and thought. Zhao's former policy secretary Bao Tong describes how a judicial agency consulted Zhao on how a major case was to be decided. Zhao simply replied: "According to the law." He allowed the judicial system to be independent, saying that the Party would not be involved in the legal process. He also charted a completely different path than before by declaring that the Party would not interfere in artistic expression.

However, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang offended too many of their peers with their anti-corruption stance and political reforms. Hu was forced to resign as Party general secretary, while Zhao faced the Tiananmen incident after he took over, and was no match for the blowback from the conservatives. He was placed under house arrest until his death.

On 18 October 2019, in the year he would have turned 100, Zhao Ziyang was finally buried in Changping Cemetery in Beijing. Looking at how he and Hu Yaobang both disappeared from the annals of the Communist Party, it is easy to see why he is considered a tragic figure.

Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang may have tasted something akin to free democratic thinking, but for them it might have been like a shooting star, gone before they could see or grasp it clearly. And before they knew it, they found themselves stuck with no way out, in the very system that they had given their lives to build.

Yin Haiguang - The firebrand

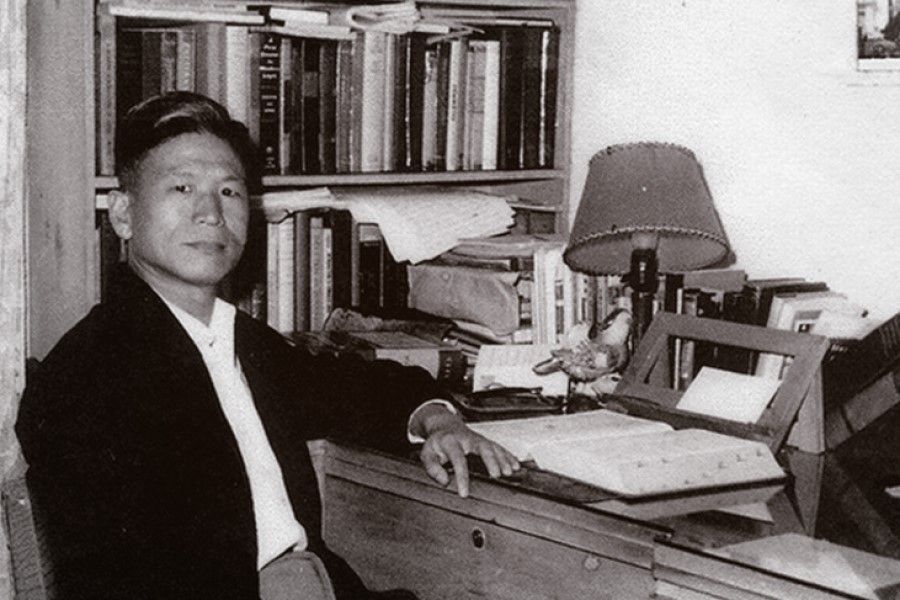

Yin Haiguang's ancestors were originally from Huanggang county, Hubei. He was a rebellious child but fell in love with philosophy in high school, and translated most of the book The Road to Serfdom by philosopher Friedrich Hayek. Well-known philosopher Jin Yuelin saw his potential and mentored him to a place in the National Southwest Associated University to study philosophy.

After World War II, Yin joined the Kuomintang and worked for its communications department, becoming the editor of Central Daily News while teaching philosophy at the University of Nanking.

In 1949, Yin followed the Kuomintang to Taiwan, where he did not like what he saw of political developments. He wrote frequent editorials criticising the Kuomintang, even denouncing the military and government personnel who had followed Chiang Kai-shek to Taiwan as "political garbage". In the end, under the collective censuring of his own party, he was forced to leave Central Daily News. He went on to teach philosophy at National Taiwan University (NTU), while writing for Free China Journal (FCJ).

FCJ was a political publication started by Hu Shih, Fu Ssu-nien, Lei Chen, and other liberal intellectuals who had moved to Taiwan from mainland China. It was originally meant to be a platform against Communist thought, but was not allowed to be distributed in mainland China. Furthermore, after the Korean War broke out, Chiang Kai-shek regained US support and tightened his authoritarian rule. FCJ gradually shifted its editorial focus to Taiwan's domestic affairs and the Kuomintang administration and policies, with Hu Shih even proposing that Taiwan should have an opposition.

FCJ ran many essays objecting to Chiang Kai-shek having three terms in office, with several advocating a strong opposition for more healthy party politics. Lei Chen and his group walked the talk by gathering Taiwan's local elites to form an opposition party. The 1 September 1960 issue of FCJ carried an editorial by Yin Haiguang titled "The great river flows ever eastward" (《大江东流挡不住》), trumpeting the dawn of the new party. This finally crossed the line, and on 4 September 1960, the military court meted out heavy sentences to Lei Chen and his associates for sedition, and FCJ was shut down.

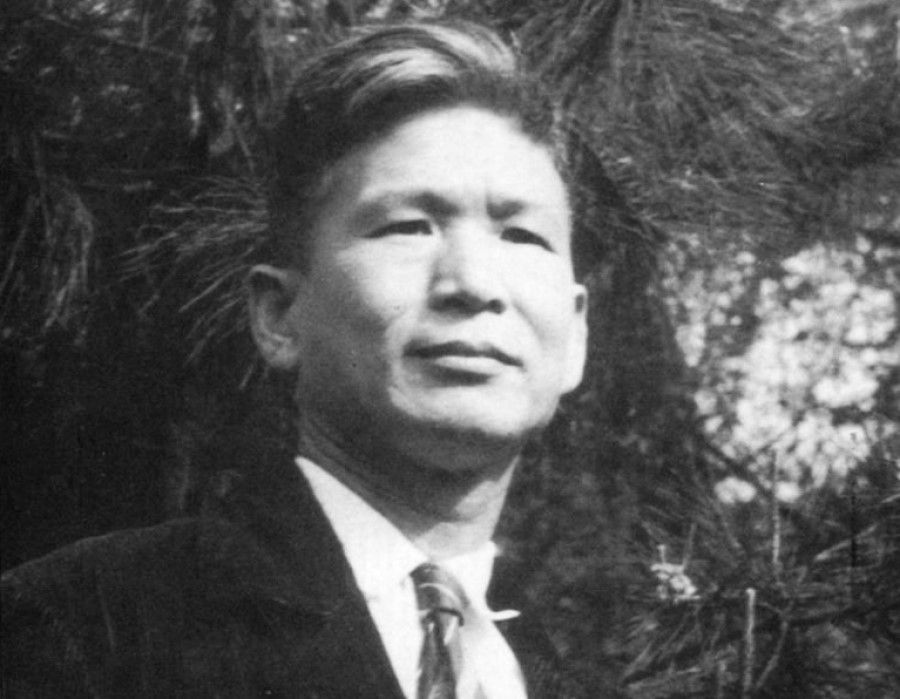

Subsequently, the authorities launched a smear campaign against Yin. Many of his books were banned, which impacted his income. By 1964, even a monthly government subsidy of US$60 had been withdrawn, putting Yin in difficult straits. Also, being wary of Yin's influence, the authorities pressured NTU not to continue employing him. Many of his colleagues and students at the philosophy department were also seen as his "cronies" and lost their positions.

Yin Haiguang always prided himself on being a liberalist. This admirer of Bertrand Russell, Karl Popper, and Hayek believed in dying for a cause rather than staying alive in silence.

Even when unemployed, Yin Haiguang's movements were monitored - he was as good as confined to his lodgings at Lane 18, Wenzhou Street in Taipei. An invitation to Yin from Harvard University was denied by the Kuomintang government; Friedrich Hayek was unable to meet Yin in Taiwan. A frustrated Yin eventually died of gastric cancer before the age of 50. His student, Taiwanese writer Li Ao, said, "Every day when he spoke of Chiang Kai-shek, he got so angry he had gastric problems and could not eat."

Yin Haiguang always prided himself on being a liberalist. This admirer of Bertrand Russell, Karl Popper, and Hayek believed in dying for a cause rather than staying alive in silence. He wrote many essays on philosophy and free thought, and is considered among those who laid the foundations for liberal thought in Taiwan. Like Hu Shih and his generation, Yin was full of hope for freedom and democracy in China, but ended his days in disappointment amid authoritarian politics.

Neither Yin Haiguang nor Zhao Ziyang used their original names. Yin was born Yin Fusheng, while Zhao was born Zhao Xiuye. Perhaps they changed their names in their youth out of some hope they held for their lives?

After Yin's death, his following in Taiwan continues to uphold and advocate his beliefs. As for Zhao, he is still waiting for his supporters to come forward to prove his virtues and restore his honour.