World Report 2011 - Human Rights Watch

World Report 2011 - Human Rights Watch

World Report 2011 - Human Rights Watch

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

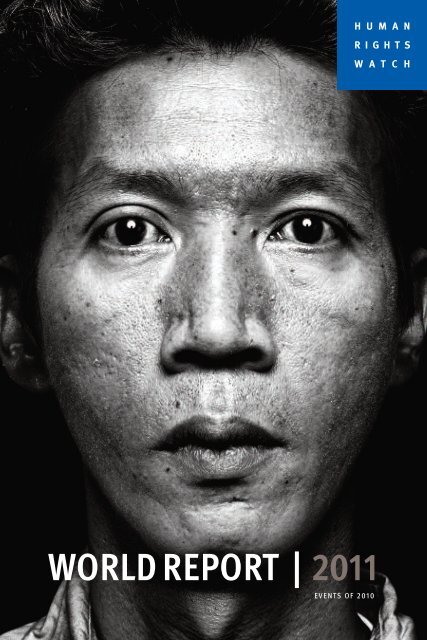

H U M A NR I G H T SW A T C HWORLD REPORT | <strong>2011</strong>E V E N T S O F 2010

H U M A NR I G H T SW A T C HWORLD REPORT<strong>2011</strong>E V E N T S O F 2 01 0

Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>All rights reserved.Printed in the United States of AmericaISBN-13: 978-1-58322-921-7Front cover photo: Aung Myo Thein, 42, spent more than six years in prison in Burma for hisactivism as a student union leader. More than 2,200 political prisoners—including artists,journalists, students, monks, and political activists—remain locked up in Burma's squalidprisons. © 2010 Platon for <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>Back cover photo: A child migrant worker from Kyrgyzstan picks tobacco leaves inKazakhstan. Every year thousands of Kyrgyz migrant workers, often together with their children,find work in tobacco farming, where many are subjected to abuse and exploitation byemployers. © 2009 Moises Saman/Magnum for <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>Cover and book design by Rafael Jiménez350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floorNew York, NY 10118-3299 USATel: +1 212 290 4700Fax: +1 212 736 1300hrwnyc@hrw.org1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500Washington, DC 20009 USATel: +1 202 612 4321Fax: +1 202 612 4333hrwdc@hrw.org2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd FloorLondon N1 9HF, UKTel: +44 20 7713 1995Fax: +44 20 7713 1800hrwuk@hrw.org27 Rue de Lisbonne75008 Paris, FranceTel: +33 (0) 1 41 92 07 34Fax: +33 (0) 1 47 22 08 61paris@hrw.orgAvenue des Gaulois, 71040 Brussels, BelgiumTel: + 32 (2) 732 2009Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471hrwbe@hrw.org51 Avenue Blanc, Floor 6,1202 Geneva, SwitzerlandTel: +41 22 738 0481Fax: +41 22 738 1791hrwgva@hrw.orgPoststraße 4-510178 Berlin, GermanyTel: +49 30 2593 06-10Fax: +49 30 2593 06-29berlin@hrw.org1st fl, Wilds ViewIsle of HoughtonBoundary Road (at Carse O’Gowrie)Parktown, 2198 South AfricaTel: +27-11-484-2640, Fax: +27-11-484-2641#4A, Meiji University Academy Common bldg. 7F, 1-1,Kanda-Surugadai, Chiyoda-kuTokyo 101-8301 JapanTel: +81-3-5282-5160, Fax: +81-3-5282-5161tokyo@hrw.orgMansour Building 4th Floor, Apt. 26Nicholas Turk StreetMedawar, Beirut, Lebanon 20753909Tel: +961-1-447833, Fax +961-1-446497www.hrw.org

<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> is dedicated to protecting thehuman rights of people around the world.We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination,to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumaneconduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice.We investigate and expose human rights violations and holdabusers accountable.We challenge governments and those who hold power to endabusive practices and respect international human rights law.We enlist the public and the international community tosupport the cause of human rights for all.

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>AcknowledgmentsA compilation of this magnitude requires contribution from a largenumber of people, including most of the <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> staff.The contributors were:Pema Abrahams, Brad Adams, Maria Aissa de Figueredo, Setenay Akdag, Brahim Alansari,Chris Albin-Lackey, Yousif al-Timimi, Joseph Amon, Amy Auguston, Leeam Azulay,Clive Baldwin, Neela Banerjee, Shantha Barriga, Jo Becker, Fatima-Zahra Benfkira,Nicholas Bequelin, Andrea Berg, Carroll Bogert, Philippe Bolopion, Tess Borden,Amy Braunschweiger, Sebastian Brett, Reed Brody, Christen Broecker, Jane Buchanan,Wolfgang Buettner, Maria Burnett, Elizabeth Calvin, Haleh Chahrokh, Anna Chaplin,Grace Choi, Sara Colm, Jon Connolly, Adam Coogle, Kaitlin Cordes, Zama Coursen-Neff,Emma Daly, Philippe Dam, Kiran D’Amico, Sara Darehshori, Juliette de Rivero, KristinaDeMain, Rachel Denber, Richard Dicker, Boris Dittrich, Kanae Doi, Corinne Dufka, AndrejDynko, Jessica Evans, Elizabeth Evenson, Jean-Marie Fardeau, Guillermo Farias, Jamie Fellner,Bill Frelick, Arvind Ganesan, Meenakshi Ganguly, Liesl Gerntholtz, Alex Gertner,Neela Ghoshal, Thomas Gilchrist, Allison Gill, Antonio Ginatta, Giorgi Gogia, Eric Goldstein,Steve Goose, Yulia Gorbunova, Ian Gorvin, Jessie Graham, Laura Graham, Eric Guttschuss,Danielle Haas, Andreas Harsono, Ali Dayan Hasan, Leslie Haskell, Jehanne Henry,Eleanor Hevey, Peggy Hicks, Saleh Hijazi, Nadim Houry, Lindsey Hutchison, Peter Huvos,Claire Ivers, Balkees Jarrah, Rafael Jiménez, Preeti Kannan, Tiseke Kasambala, Aruna Kashyap,Nick Kemming, Elise Keppler, Amr Khairy, Nadya Khalife, Viktoria Kim, Carolyn Kindelan,Juliane Kippenberg, Amanda Klasing, Kyle Knight, Soo Ryun Kwon, Erica Lally, Mignon Lamia,Adrianne Lapar, Leslie Lefkow, Lotte Leicht, Iain Levine, Diederik Lohman, Tanya Lokshina,Jiaying Long, Anna Lopriore, Linda Louie, Drake Lucas, Lena Miriam Macke, Tom Malinowski,Noga Malkin, Ahmed Mansour, Joanne Mariner Edmon Marukyan, Dave Mathieson,Géraldine Mattioli-Zeltner, Veronica Matushaj, Maria McFarland, Megan McLemore,Amanda McRae, Wenzel Michalski, Kathy Mills, Lisa Misol, Marianne Mollmann, Ella Moran,Heba Morayef, Mani Mostofi, Priyanka Motaparthy, Rasha Moumneh, Siphokazi Mthathi,Jim Murphy, Samer Muscati, Dipika Nath, Stephanie Neider, Rachel Nicholson,Agnes Ndige Muriungi Odhiambo, Jessica Ognian, Erin O’Leary, Alison Parker, Sarah Parkes,Elaine Pearson, Rona Peligal, Sasha Petrov, Sunai Phasuk, Enrique Piraces, Laura Pitter,

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSDinah PoKempner, Tom Porteous, Jyotsna Poudyal, Andrea Prasow, Marina Pravdic,Mustafa Qadri, Daniela Ramirez, Ben Rawlence, Rachel Reid, Aisling Reidy, Meghan Rhoad,Sophie Richardson, Lisa Rimli, Mihra Rittmann, Phil Robertson, Kathy Rose, James Ross,Kenneth Roth, Faraz Sanei, Joe Saunders, Ida Sawyer, Max Schoening, Jake Scobey-Thal,David Segall, Kathryn Semogas, Kay Seok, Jose Serralvo, Anna Sevortian Vikram Shah,Bede Sheppard, Robin Shulman, Gerry Simpson, Emma Sinclair-Webb, Peter Slezkine,Daniel W. Smith, Ole Solvang, Mickey Spiegel, Xabay Spinka, Nik Steinberg, Joe Stork,Judith Sunderland, Steve Swerdlow, Veronika Szente Goldston, Maya Taal, Tamara Taraciuk,Letta Tayler, Carina Tertsakian, Elena Testi, Tej Thapa, Laura Thomas, Katherine Todrys,Simone Troller, Wanda Troszczynska-van Genderen, Farid Tukhbatullin, Bill Van Esveld,Gauri Van Gulik, Anneke Van Woudenberg, Elena Vanko, Nisha Varia, Rezarta Veizaj,Jamie Vernaelde, José Miguel Vivanco, Florentine Vos, Janet Walsh, Ben Ward,Matthew Wells, Lois Whitman, Sarah Leah Whitson, Christoph Wilcke, Daniel Wilkinson,Minky Worden, Riyo Yoshioka.Joe Saunders edited the report with assistance from Ian Gorvin, Danielle Haas, Iain Levine,and Robin Shulman. Brittany Mitchell coordinated the editing process. Layout and productionwere coordinated by Grace Choi and Rafael Jiménez, with assistance from AnnaLopriore, Veronica Matushaj, Jim Murphy, Enrique Piraces, and Kathy Mills.Leeam Azulay, Adam Coogle, Guillermo Farias, Alex Gertner, Thomas Gilchrist,Lindsey Hutchison, Carolyn Kindelan, Kyle Knight, Erica Lally, Adrianne Lapar, Linda Louie,Stephanie Neider, Erin O’Leary, Jessica Ognian, Marina Pravdic, Daniela Ramirez,Jake Scobey-Thal, David Segall, and Vikram Shah proofread the report.For a full list of <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> staff, please go to our website:www.hrw.org/about/info/staff.html.

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>

This 21st annual <strong>World</strong> <strong>Report</strong> is dedicated to the memoryof our beloved colleague Ian Gorvin, who died of cancer onNovember 15, 2010, at age 48. Ian, senior program officer at<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>, edited the <strong>World</strong> <strong>Report</strong> for most of thepast decade, was an expert on human rights issues in Europeand around the world, and made lasting contributions to thehuman rights movement through his work with AmnestyInternational and the Organization for Security andCo-operation in Europe as well as <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>.An experienced activist, Ian brought good judgment as wellas linguistic savvy and an unerring eye for detail to hisediting. And he never lost sight of our mission: to tell thestories of victims of human rights violations with dignity andcompassion and to press for justice to ensure that othersdo not suffer the same fate. He was ever the voice of calm,sensible advice, with an understated but potent sense ofhumor. We miss him enormously.ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Table of ContentsA Facade of ActionThe Misuse of Dialogue and Cooperation with <strong>Rights</strong> Abusers 1by Kenneth RothWhose News?The Changing Media Landscape and NGOs 24by Carroll BogertSchools as BattlegroundsProtecting Students, Teachers, and Schools from Attack 37by Zama Coursen-Neff and Bede SheppardPhoto EssaysBurma, Kyrgyzstan, Kuwait, Kazakhstan, and The Lord’s Resistance Army 51Africa 75Angola 76Burundi 83Chad 92Côte d’Ivoire 97Democratic Republic of Congo 103Equatorial Guinea 111Eritrea 116Ethiopia 121Guinea 127Kenya 133Liberia 142Nigeria 148Rwanda 154Sierra Leone 160

TABLE OF CONTENTSSomalia 165South Africa 171Sudan 176Uganda 185Zimbabwe 194Americas 203Argentina 204Bolivia 210Brazil 215Chile 222Colombia 227Cuba 233Ecuador 238Guatemala 243Haiti 248Honduras 252Mexico 256Peru 263Venezuela 268Asia 275Afghanistan 276Bangladesh 282Burma 288Cambodia 295China 303India 315

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Indonesia 321Malaysia 331Nepal 337North Korea 343Pakistan 348Papua New Guinea 355The Philippines 359Singapore 365Sri Lanka 370Thailand 376Vietnam 384Europe and Central Asia 391Armenia 392Azerbaijan 398Belarus 404Bosnia and Herzegovina 410Croatia 415European Union 420Georgia 437Kazakhstan 443Kyrgyzstan 449Russia 456Serbia 463Tajikistan 474Turkey 479Turkmenistan 485Ukraine 491Uzbekistan 497

TABLE OF CONTENTSMiddle East and North Africa 505Algeria 506Bahrain 511Egypt 517Iran 523Iraq 530Israel/Occupied Palestinian Territories 536Jordan 545Kuwait 551Lebanon 556Libya 562Morocco and Western Sahara 568Saudi Arabia 576Syria 584Tunisia 591United Arab Emirates 597Yemen 602United States 6092010 <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> Publications 629

INTRODUCTIONA Facade of Action:The Misuse of Dialogue and Cooperationwith <strong>Rights</strong> AbusersBy Kenneth RothIn last year’s <strong>World</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> highlighted the intensifyingattacks by abusive governments on human rights defenders, organizations,and institutions. This year we address the flip side of the problem–the failureof the expected champions of human rights to respond to the problem, defendthose people and organizations struggling for human rights, and stand upfirmly against abusive governments.There is often a degree of rationality in a government’s decision to violatehuman rights. The government might fear that permitting greater freedomwould encourage people to join together in voicing discontent and thus jeopardizeits grip on power. Or abusive leaders might worry that devotingresources to the impoverished would compromise their ability to enrich themselvesand their cronies.International pressure can change that calculus. Whether exposing or condemningabuses, conditioning access to military aid or budgetary support onending them, imposing targeted sanctions on individual abusers, or even callingfor prosecution and punishment of those responsible, public pressure raisesthe cost of violating human rights. It discourages further oppression, signalingthat violations cannot continue cost-free.All governments have a duty to exert such pressure. A commitment to humanrights requires not only upholding them at home but also using available andappropriate tools to convince other governments to respect them as well.1

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>No repressive government likes facing such pressure. Today many are fightingback, hoping to dissuade others from adopting or continuing such measures.That reaction is hardly surprising. What is disappointing is the number of governmentsthat, in the face of that reaction, are abandoning public pressure.With disturbing frequency, governments that might have been counted on togenerate such pressure for human rights are accepting the rationalizationsand subterfuges of repressive governments and giving up. In place of a commitmentto exerting public pressure for human rights, they profess a preferencefor softer approaches such as private “dialogue” and “cooperation.”There is nothing inherently wrong with dialogue and cooperation to promotehuman rights. Persuading a government through dialogue to genuinely cooperatewith efforts to improve its human rights record is a key goal of humanrights advocacy. A cooperative approach makes sense for a government thatdemonstrably wants to respect human rights but lacks the resources or technicalknow-how to implement its commitment. It can also be useful for face-savingreasons–if a government is willing to end violations but wants to appear toact on its own initiative. Indeed, <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> often engages quietlywith governments for such reasons.But when the problem is a lack of political will to respect rights, public pressureis needed to change the cost-benefit analysis that leads to the choice ofrepression over rights. In such cases, the quest for dialogue and cooperationbecomes a charade designed more to appease critics of complacency than tosecure change, a calculated diversion from the fact that nothing of consequenceis being done. Moreover, the refusal to use pressure makes dialogueand cooperation less effective because governments know there is nothing tofear from simply feigning serious participation.Recent illustrations of this misguided approach include ASEAN’s tepidresponse to Burmese repression, the United Nations’ deferential attitude2

INTRODUCTIONtoward Sri Lankan atrocities, the European Union’s obsequious approach toUzbekistan and Turkmenistan, the soft Western reaction to certain favoredrepressive African leaders such as Paul Kagame of Rwanda and Meles Zenawiof Ethiopia, the weak United States policy toward Saudi Arabia, India’s pliantposture toward Burma and Sri Lanka, and the near-universal cowardice in confrontingChina’s deepening crackdown on basic liberties. In all of these cases,governments, by abandoning public pressure, effectively close their eyes torepression.Even those that shy away from using pressure in most cases are sometimeswilling to apply it toward pariah governments, such as North Korea, Iran,Sudan, and Zimbabwe, whose behavior, whether on human rights or othermatters, is so outrageous that it overshadows other interests. But in too manycases, governments these days are disappointingly disinclined to use publicpressure to alter the calculus of repression.When governments stop exerting public pressure to address human rights violations,they leave domestic advocates–rights activists, sympathetic parliamentarians,concerned journalists–without crucial support. Pressure fromabroad can help create the political space for local actors to push their governmentto respect rights. It also can let domestic advocates know that theyare not alone, that others stand with them. But when there is little or no suchpressure, repressive governments have a freer hand to restrict domestic advocates,as has occurred in recent years in Russia, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Cambodia,and elsewhere. And because dialogue and cooperation look too much likeacquiescence and acceptance, domestic advocates sense indifference ratherthan solidarity.3

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>A Timid Response to RepressionIn recent years the use of dialogue and cooperation in lieu of public pressurehas emerged with a vengeance at the UN, from Secretary-General Ban Ki-moonto many members of the <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> Council. In addition, the EU seems tohave become particularly infatuated with the idea of dialogue and cooperation,with the EU’s first high representative for foreign affairs and security policy,Catherine Ashton, repeatedly expressing a preference for “quiet diplomacy”regardless of the circumstances. Leading democracies of the global South,such as South Africa, India, and Brazil, have promoted quiet demarches as apreferred response to repression. The famed eloquence of US President BarackObama has sometimes eluded him when it comes to defending human rights,especially in bilateral contexts with, for example, China, India, and Indonesia.Obama has also not insisted that the various agencies of the US government,such as the Defense Department and various embassies, convey stronghuman rights messages consistently–a problem, for example, in Egypt,Indonesia, and Bahrain.This is a particularly inopportune time for proponents of human rights to losetheir public voice, because various governments that want to prevent the vigorousenforcement of human rights have had no qualms about raising theirs.Many are challenging first principles, such as the universality of human rights.For example, some African governments complain that the InternationalCriminal Court’s current focus on Africa is selective and imperialist, as if thefate of a few African despots were more important than the suffering of countlessAfrican victims. China’s economic rise is often cited as reason to believethat authoritarian government is more effective for guiding economic developmentin low-income countries, even though unaccountable governments aremore likely to succumb to corruption and less likely to respond to or invest inpeople’s most urgent needs (as demonstrated by the rising number of protestsin China–some 90,000 annually by the government’s own count–fueled by4

INTRODUCTIONgrowing discontent over the corruption and arbitrariness of local officials).Some governments, eager to abandon long-established rules for protectingcivilians in time of war or threatened security, justify their own violations ofthe laws of war by citing Sri Lanka’s indiscriminate attacks in its victory overthe rebel Tamil Tigers, or Western (and especially US) tolerance of torture andarbitrary detention in combating terrorism. Governments that lose their voiceon human rights effectively abandon these crucial debates to the opponentsof universal human rights enforcement.Part of this reticence is due to a crisis of confidence. The shifting global balanceof power (particularly the rise of China), an intensified competition formarkets and natural resources at a time of economic turmoil, and the declinein moral standing of Western powers occasioned by their use with impunity ofabusive counterterrorism techniques have made many governments less willingto take a strong public stand in favor of human rights.Ironically, some of the governments most opposed to using pressure to promotehuman rights have no qualms about using pressure to deflect humanrights criticism. China, for example, pulled out all stops in an ultimately unsuccessfuleffort to suppress a report to the UN Security Council on the discoveryof Chinese weaponry in Darfur despite an arms embargo. Sri Lanka did thesame in an unsuccessful effort to quash a UN advisory panel on accountabilityfor war crimes committed during its armed conflict with the Tamil Tigers. Chinaalso mounted a major lobbying effort to prevent the awarding of the NobelPeace Prize to imprisoned Chinese writer and human rights activist Liu Xiaobo,and when that failed, it tried unsuccessfully to discourage governments fromattending the award ceremony in Norway. China made a similar effort to blocka proposed UN commission of inquiry into war crimes committed in Burma.5

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>The United Nations and Its Member StatesThe obsession with dialogue and cooperation is particularly intense at the UN<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> Council in Geneva, where many of the members insist that theCouncil should practice “cooperation, not condemnation.” A key form of pressureat the Council is the ability to send fact-finders to expose what abuseswere committed and to hold governments accountable for not curtailing abuses.One important medium for these tools is a resolution aimed at a particularcountry or situation. Yet many governments on the Council eschew any countryresolution designed to generate pressure (except in the case of the Council’sperennial pariah, Israel). As China explained (in the similar context of the UNGeneral Assembly), ”[s]ubmitting [a] country specific resolution…will make theissue of human rights politicized and is not conducive to genuine cooperationon human rights issues.” The African Group at the UN has said it will supportcountry resolutions only with the consent of the target government, in otherwords, only when the resolution exerts no pressure at all. This approach wastaken to an extreme after Sri Lanka launched indiscriminate attacks on civiliansin the final months of its war with the Tamil Tigers–rather than condemnthese atrocities, a majority of Council members overcame a minority’s objectionsand voted to congratulate Sri Lanka on its military victory without mentioninggovernment atrocities.If members of the Council want dialogue and cooperation to be effective inupholding human rights, they should limit use of these tools to governmentsthat have demonstrated a political will to improve. But whether out of calculationor cowardice, many Council members promote dialogue and cooperationas a universal prescription without regard to whether a government has thepolitical will to curtail its abusive behavior. They thus resist tests for determiningwhether a government’s asserted interest in cooperation is a ploy to avoidpressure or a genuine commitment to improvement–tests that might look tothe government’s willingness to acknowledge its human rights failings, wel-6

INTRODUCTIONcome UN investigators to examine the nature of the problem, prescribe solutions,and embark upon reforms. The enemies of human rights enforcementoppose critical resolutions even on governments that clearly fail these tests,such as Burma, Iran, North Korea, Sri Lanka, and Sudan.Similar problems arise at the UN General Assembly. As the Burmese militaryreinforced its decades-long rule with sham elections designed to give it a civilianfacade, a campaign got under way to intensify pressure by launching aninternational commission of inquiry to examine the many war crimes committedin the country’s long-running armed conflict. A commission of inquirywould be an excellent tool for showing that such atrocities could no longer becommitted with impunity. It would also create an incentive for newer membersof the military-dominated government to avoid the worst abuses of the past.The idea of a commission of inquiry, originally proposed by the independentUN special rapporteur on Burma, has received support from, among others,the US, the United Kingdom, France, Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and NewZealand.Yet some have refused to endorse a commission of inquiry on the spuriousgrounds that it would not work without the cooperation of the Burmese junta.EU High Representative Ashton, in failing to embrace this tool, said: “Ideally,we should aim at ensuring a measure of cooperation from the national authorities.”Similarly, a German Foreign Ministry spokeswoman said that, to helpadvance human rights in the country, it is “crucial to find some co-operationmechanism with the [Burmese] national authorities.” Yet obtaining such cooperationfrom the Burmese military in the absence of further pressure is a pipedream.One favorite form of cooperation is a formal intergovernmental dialogue onhuman rights, such as those that many governments conduct with China andthe EU maintains with a range of repressive countries, including the former-7

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Soviet republics of Central Asia. Authoritarian governments understandablywelcome these dialogues because they remove the spotlight from humanrights discussions. The public, including domestic activists, is left in the dark,as are most government officials outside the foreign ministry. But Westerngovernments also often cite the existence of such dialogues as justification fornot speaking concretely about human rights violations and remedies in moremeaningful settings–as Sweden did, for example, during its EU presidencywhen asked why human rights had not featured more prominently at the EU-Central Asia ministerial conference.<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>’s own experience shows that outspoken commentary onhuman rights practices need not preclude meaningful private dialogue withgovernments. <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> routinely reports on abuses and generatespressure for them to end, but that has not stood in the way of active engagementwith many governments that are the subject of these reports. Indeed,governments are often more likely to engage with <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>,because the sting of public reporting, and a desire to influence it, spurs themto dialogue. If a nongovernmental organization can engage with governmentswhile speaking out about their abuses, certainly governments should be ableto do so as well.The Need for BenchmarksDialogues would have a far greater impact if they were tied to concrete andpublicly articulated benchmarks. Such benchmarks would give clear directionto the dialogue and make participants accountable for concrete results. Butthat is often exactly what dialogue participants want to avoid. The failure toset clear, public benchmarks is itself evidence of a lack of seriousness, anunwillingness to deploy even the minimum pressure needed to make dialoguemeaningful. The EU, for example, has argued that publicly articulated benchmarkswould introduce tension into a dialogue and undermine its role as a8

INTRODUCTION“confidence-building exercise,” as if the purpose of the dialogue were to promotewarm and fuzzy feelings rather than to improve respect for human rights.Moreover, repressive governments have become so adept at manipulatingthese dialogues, and purported promoters of human rights so dependent onthem as a sign that they are “doing something,” that the repressors have managedto treat the mere commencement or resumption of dialogue as a sign of“progress.” Even supposed rights-promoters have fallen into this trap. Forexample, a 2008 progress report by the EU on the implementation of itsCentral Asia strategy concluded that things were going well but gave nospecifics beyond “intensified political dialogue” as a measurement of“progress.”Even when benchmarks exist, Western governments’ willingness to ignorethem when they prove inconvenient undermines their usefulness. For example,the EU’s bilateral agreements with other countries are routinely conditionedon basic respect for human rights, but the EU nonetheless concluded asignificant trade agreement and pursued a full partnership and cooperationagreement with Turkmenistan, a severely repressive government that cannotconceivably be said to comply with the agreements’ human rights conditions.It is as if the EU announced in advance that its human rights conditions weremere window-dressing, not to be taken seriously. The EU justified this step inthe name of “deeper engagement” and a new “framework for dialogue andcooperation.”Similarly, despite Serbia’s failure to apprehend and surrender for trial indictedwar crimes suspect Ratko Mladic (the former Bosnian Serb military leader)–alitmus test for the war-crimes cooperation that the EU has repeatedly insistedis a requirement for beginning discussions with Serbia about its accession tothe EU–the EU agreed to start discussions anyway. The EU also gradually liftedsanctions imposed on Uzbekistan after security forces massacred hundreds in9

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>2005 in the city of Andijan, even though no steps had been taken toward permittingan independent investigation–originally the chief condition for liftingsanctions–let alone prosecuting those responsible or doing anything else thatthe EU had called for, such as releasing all wrongfully imprisoned humanrights activists.By the same token, the Obama administration in its first year simply ignoredthe human rights conditions on the transfer of military aid to Mexico, underthe Merida Initiative, even though Mexico had done nothing as requiredtoward prosecuting abusive military officials in civilian courts. While in its secondyear the administration did withhold a small fraction of funding, it onceagain certified–despite clear evidence to the contrary–that Mexico was meetingMerida’s human rights requirements. The US also signed a funding compactwith Jordan under the Millennium Challenge Corporation even thoughJordan had failed to improve its failing grades on the MCC’s benchmarks forpolitical rights and civil liberties.Weak LeadershipUN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has been notably reluctant to put pressureon abusive governments. As secretary-general, he has two main tools at hisdisposal to promote human rights–private diplomacy and his public voice. Hecan nudge governments to change through his good offices, or he can use thestature of his office to expose those who are unwilling to change. Ban’s disinclinationto speak out about serious human rights violators means he is oftenchoosing to fight with one hand tied behind his back. He did make strongpublic comments on human rights when visiting Turkmenistan andUzbekistan, but he was much more reticent when visiting a powerful countrylike China. And he has placed undue faith in his professed ability to convinceby private persuasion the likes of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir,10

INTRODUCTIONBurmese military leader Than Shwe, and Sri Lankan President MahindaRajapaksa.Worse, far from condemning repression, Ban sometimes went out of his way toportray oppressive governments in a positive light. For example, in the daysbefore Burma’s sham elections in November, Ban contended that it was “nottoo late” to “make this election more inclusive and participatory” by releasingpolitical detainees–an unlikely eventuality that, even if realized, would nothave leveled the severely uneven electoral playing field. Even after the travestywas complete, Ban said only that the elections had been “insufficientlyinclusive, participatory and transparent”–a serious understatement.When he visited China the same month, Ban made no mention of humanrights in his meeting with Chinese President Hu Jintao, leaving the topic forlesser officials. That omission left the impression that, for the secretary-general,human rights were at best a second-tier priority. In commenting on theawarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, the imprisoned Chinesehuman rights activist, Ban never congratulated Liu or called for his releasefrom prison but instead praised Beijing by saying: “China has achievedremarkable economic advances, lifted millions out of poverty, broadenedpolitical participation and steadily joined the international mainstream in itsadherence to recognized human rights instruments and practices.”The new British prime minister, David Cameron, did only marginally better duringhis visit to China. He did not mention Liu in his formal meeting withChinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, saving the matter for informal talks overdinner. And his public remarks stayed at the level of generality with which theChinese governments itself is comfortable–the need for “greater politicalopening” and the rule of law–rather than mention specific cases of imprisonedgovernment critics or other concrete rights restrictions.11

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>The government of German Chancellor Angela Merkel showed a similar lack ofcourage in its dealings with China. “Dialogue” is the German government’swidely mentioned guiding principle, and Merkel in public remarks during herlatest visit to China made only the slightest passing reference to human rights,although she claimed to have mentioned the issue privately. At the “ChinaMeets Europe” summit in Hamburg, German Foreign Minister GuidoWesterwelle, without mentioning concrete abuses, cited an “intensive rule oflaw dialogue” and a “human rights dialogue” as “build[ing] a solid foundationfor a real partnership between Germany and China.” In France, PresidentNicolas Sarkozy, as he was about to welcome Chinese President Hu Jintao inParis in November, did not even congratulate Liu Xiaobo for having beenawarded the Nobel Peace Prize.With respect to Saudi Arabia, the US government in 2005 established a“strategic dialogue” which, because of Saudi objections, did not mentionhuman rights as a formal subject but relegated the topic to the “Partnership,Education, Exchange, and <strong>Human</strong> Development Working Group.” Even thatdialogue then gradually disappeared. While the US government contributed tokeeping Iran off the board of the new UN Women agency in 2010 because ofits mistreatment of women, it made no such effort with Saudi Arabia, whichhas an abysmal record on women but was given a seat by virtue of its financialcontribution. Similarly, the UK has maintained a quiet “two kingdoms” dialoguewith Saudi Arabia since 2005. Its launching included only oblique referencesto human rights, and it has exerted no discernible pressure on theSaudi government to improve its rights record.Other Interests at StakeSometimes those who promote quiet dialogue over public pressure argue efficacy,although often other interests seem to be at play. In Uzbekistan, whichprovides an important route for resupplying NATO troops in Afghanistan, the12

INTRODUCTIONEU argued that targeted sanctions against those responsible for the Andijanmassacre were “alienating” the government and “standing in the way of a constructiverelationship,” as if making nice to a government that aggressivelydenied any responsibility for killing hundreds of its citizens would be moresuccessful at changing it than sustained pressure. In making the case for whyhuman rights concerns should not stand in the way of a new partnership andcooperation agreement with severely repressive Turkmenistan, a country withlarge gas reserves, the EU resorts to similar stated fears of alienation. To avoidpublic indignation if it were to openly abandon human rights in favor of theseother interests, the EU feigns ongoing concern through the medium of privatedialogue.A similar dynamic is at play in China, where Western governments seek economicopportunity as well as cooperation on a range of global and regionalissues. For example, in its first year in office, the Obama administrationseemed determined to downplay any issue, such as human rights, that mightraise tensions in the US-China relationship. President Obama deferred meetingwith the Dalai Lama until after his trip to China and refused to meet withChinese civil society groups during the trip, and Secretary of State HillaryClinton announced that human rights “can’t interfere” with other US interestsin China. Obama’s efforts to ingratiate himself with Chinese President HuJintao gained nothing discernible while it reinforced China’s view of the US asa declining power. That weakness only heightened tension when, in Obama’ssecond year in office, he and Secretary Clinton rediscovered their humanrights voice on the case of Liu Xiaobo, although it remains to be seen whetherthey will be outspoken on rights during the January <strong>2011</strong> US-China summit.Western governments also have been reluctant to exert pressure for humanrights on governments that they count as counterterrorism allies. For example,the Obama administration and the Friends of Yemen, a group of states andintergovernmental organizations established in January 2010, have not condi-13

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>tioned military or development assistance to Yemen on human rights improvements,despite a worsening record of abusive conduct by Yemeni securityforces and continuing government crackdowns on independent journalists andlargely peaceful southern separatists.US policy toward Egypt shows that pressure can work. In recent years, the USgovernment has maintained a quiet dialogue with Egypt. Beginning in 2010,however, the White House and State Department repeatedly condemned abuses,urged repeal of Egypt’s emergency law, and called for free elections. Thesepublic calls helped to secure the release of several hundred politicaldetainees held under the emergency law. Egypt also responded with anger–forexample, waging a lobbying campaign to stop a US Senate resolution condemningits human rights record. The reaction was designed to scare US diplomatsinto resuming a quieter approach, but in fact it showed that Egypt is profoundlyaffected by public pressure from Washington.Defending <strong>Rights</strong> by OsmosisOne common rationalization offered for engagement without pressure is thatrubbing shoulders with outsiders will somehow help to convert abusive agentsof repressive governments. The Pentagon makes that argument in the case ofUzbekistan and Sri Lanka, and the US government adopted that line to justifyresuming military aid to Indonesia’s elite special forces (Kopassus), a unit witha long history of severe abuse, including massacres in East Timor and “disappearances”of student leaders in Jakarta. With respect to Kopassus, while theIndonesian government’s human rights record has improved dramatically inrecent years, a serious gap remains its failure to hold senior military officersaccountable for human rights violations, even in the most high-profile cases.In 2010 the US relinquished the strongest lever it had by agreeing to lift adecade-old ban on direct military ties with Kopassus. The Indonesian militarymade some rhetorical concessions–promising to discharge convicted offend-14

INTRODUCTIONers and to take action against future offenders–but the US did not conditionresumption of aid on such changes. Convicted offenders today remain in themilitary, and there is little reason to credit the military’s future pledge given itspoor record to date. Notably, the US did not insist that Indonesian PresidentSusilo Bambang Yudhoyono authorize a special court to investigate Kopassusofficers implicated in the abduction and presumed killing of student leaders in1997-98, a step already recommended by Indonesia’s own parliament. Andthe US did not insist on ending the military’s exclusive jurisdiction over crimescommitted by soldiers.Trivializing the significance of pressure, US Defense Secretary Robert Gatesjustified resuming direct ties with Kopassus: “Working with them further willproduce greater gains in human rights for people than simply standing backand shouting at people.” Yet even as the US was finalizing terms withIndonesia on resumption of aid to Kopassus, an Indonesian general implicatedin abductions of student leaders was promoted to deputy defense ministerand a colonel implicated in other serious abuses was named deputy commanderof Kopassus.A similarly misplaced faith in rubbing shoulders with abusive forces ratherthan applying pressure on them informed President Obama’s decision to continuemilitary aid to a series of governments that use child soldiers–Chad,Sudan, Yemen, and the Democratic Republic of Congo–despite a new US lawprohibiting such aid. In the case of Congo, for example, the military has hadchildren in its ranks since at least 2002, and a 2010 UN report found a “dramaticincrease” in the number of such children in the prior year. Instead ofusing a cutoff of military assistance to pressure these governments to stopusing child soldiers, the Obama administration waived the law to give the UStime to “work with” the offending militaries.15

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Another favorite rationale for a quiet approach, heard often in dealings withChina, is that economic liberalization will lead on its own to greater politicalfreedoms–a position maintained even after three decades in which that hasnot happened. Indeed, in 2010 the opposite occurred–in its regulation of theinternet, China began using its economic clout to try to strengthen restrictionson speech, pressing businesses to become censors on its behalf. In the end, itwas a business–Google–that fought back, in part because censorship threatenedits business model. GoDaddy.com, the world’s largest web registrar, alsoannounced that it would no longer register domains in China because onerousgovernment requirements forcing disclosure of customer identities made censorshipeasier.Despite these efforts, China still leveraged access to its lucrative market togain the upper hand because others in the internet industry, such asMicrosoft, did not follow Google’s lead. Conversely, the one time that Chinabacked off was when it faced concerted pressure–it apparently abandoned its“Green Dam” censoring software when the industry, civil society, governments,and China’s own internet users all loudly protested. And even Google’slicense to operate a search engine in China was renewed, casting furtherdoubt on the idea that a public critique of China’s human rights practiceswould inevitably hurt business.<strong>Human</strong>itarian ExcusesSome governments and intergovernmental organizations contend that promotinghuman rights must take a back seat to relieving humanitarian suffering.<strong>Human</strong>itarian emergencies often require an urgent response, but this argumentbecomes yet another excuse to avoid pressure even when human rightsabuses are the cause of the humanitarian crisis. That occurred in Zimbabweduring Operation Murambatsvina (Clean the Filth), when the governmentdestroyed the homes of tens of thousands of people, and in Sri Lanka during16

INTRODUCTIONthe final stages of the civil war, when the army disregarded the plight of hundredsof thousands of Tamil civilians who were trapped in a deadly war zone.In Zimbabwe, the UN country team never publicly condemned the destructionand displacement caused by Operation Murambatsvina, and almost neverspoke out publicly about the extremely serious human rights abuses committedby Robert Mugabe’s government and the ruling Zimbabwe African NationalUnion- Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF). In fact, during his four-year tenure inZimbabwe, the UN resident representative rarely met with Zimbabwean humanrights activists, never attended any of their unfair trials, and almost neverspoke publicly about the widespread and severe human rights abuses beingcommitted. Such silence did not translate into better access to the displacedcivilian population–the Zimbabwean authorities and ZANU-PF officials continuedto restrict and manipulate humanitarian operations in Zimbabwe, and frequentlyprevented humanitarian organizations from reaching vulnerable populationssuspected of being pro-opposition. But by failing to publicly condemnthe abuses in Zimbabwe, the UN country team lost key opportunities to use itssubstantial influence as the most important implementer of humanitarian anddevelopment assistance in the country. It also left itself addressing the symptomsof repression rather than their source.By contrast, the special envoy appointed by then Secretary-General Kofi Annanto investigate Operation Murambatsvina issued a strongly worded report in2005 citing the indiscriminate and unjustified evictions and urging that thoseresponsible be brought to justice. The report led to widespread internationalcondemnation of Mugabe’s government–pressure that forced the governmentto allow greater humanitarian access to the displaced population.Similarly in Sri Lanka, in the final months of the war with the Tamil Tigers, UNpersonnel were virtually the only independent observers, giving them a uniquecapacity to alert the world to ongoing war crimes and to generate pressure to17

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>spare civilians. Instead, the UN covered up its own information about civiliancasualties, stopped the release of satellite imagery showing how dire the situationwas, and even stayed silent when local UN staff members were arbitrarilyarrested. UN officials were concerned that by speaking out they would loseaccess required to assist a population in need, but given Sri Lanka’s completedependence on international assistance to run camps that ultimately housed300,000 internally displaced persons, the UN arguably overestimated the riskof being barred from the country. In addition, the government’s use of anexpensive Washington public-relations firm to counter criticism of its war conductshowed its concern with its international image. By not speaking out, theUN lost an opportunity to influence the way the Sri Lankan army was conductingthe war and thus to prevent civilian suffering rather than simply alleviate itafter the fact. By contrast, after the conflict, when the independent UN specialrapporteur on the rights of the internally displaced spoke out about the lack offreedom of movement for the internally displaced, the government promptlybegan releasing civilians from the camps.A comparable pattern could be found in the role played by Western development-assistancebureaucracies in dealing with Rwanda and Ethiopia. Bothcountries are seen as efficient, relatively uncorrupt recipients of developmentassistance. Western donor agencies, often finding it difficult to productivelyinvest the funds that they are charged with disbursing, thus have a stronginterest in maintaining warm relationships with the governments. (Ethiopia’srole in combating the terrorist threat emanating from Somalia reinforces thisinterest.) Indeed, economic assistance to both countries has grown as theirrepression has intensified. Because it would be too callous to say that economicdevelopment justifies ignoring repression, the European Commission,the UK, several other EU states, and the US have offered various excuses, fromthe claim that public pressure will backfire in the face of national pride to theassertion that donor governments have less leverage than one might think.18

INTRODUCTIONThe result is a lack of meaningful pressure–nothing to change the cost-benefitanalysis that makes repression an attractive option. Quiet entreaties are leastlikely to be effective when they are drowned out by parallel delivery of massivequantities of aid.Dated PoliciesBrazil, India, and South Africa, strong and vibrant democracies at home,remain unsupportive of many human rights initiatives abroad, even thougheach benefitted from international solidarity in its struggle to end, respectively,dictatorship, colonization, and apartheid. Their foreign policies are oftenbased on building South-South political and economic ties and are bolsteredby reference to Western double standards, but these rationales do not justifythese emerging powers turning their backs on people who have not yet wonthe rights that their own citizens enjoy. With all three countries occupyingseats on the UN Security Council, it would be timely for them to adopt a moreresponsible position toward protecting people from the predation of less progressivegovernments.Japan traditionally has resisted a strong human rights policy in part becauseJapanese foreign policy has tended to center around promoting exports andbuilding good will, in part because the setting of foreign policy has been dominatedby bureaucrats who faced little public outcry over their inclination tomaintain smooth relations with all governments, and in part because Japanstill has not come to terms with its own abusive record in <strong>World</strong> War II.However, in recent years, partly due to a change in government and partly dueto growing pressure from the small but emerging Japanese civil society, theJapanese government has begun to be more outspoken on human rights withregard to such places as North Korea and Burma.19

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>The Chinese government is naturally reluctant to promote human rightsbecause it maintains such a repressive climate at home and does not want tobolster any international system for the protection of human rights that mightcome back to haunt it. But even China should not see turning its back on massatrocities–a practice that, one would hope, China has moved beyond–asadvancing its self-interest.ConclusionWhatever the rationalization, the quest for dialogue and cooperation is simplynot a universal substitute for public pressure as a tool to promote humanrights. Dialogue and cooperation have their place, but the burden should beon the abusive government to show a genuine willingness to improve. In theabsence of demonstrated political will, public pressure should be the defaultresponse to repression. It is understandable when governments that themselvesare serious human rights violators want to undermine the option ofpublic pressure out of fear that it will be applied to them in turn. But it isshameful when governments that purportedly promote human rights fall for, orendorse, the same ploy.Defending human rights is rarely convenient. It may sometimes interfere withother governmental interests. But if governments want to pursue those interestsinstead of human rights, they should at least have the courage to admitit, instead of hiding behind meaningless dialogues and fruitless quests forcooperation.This <strong>Report</strong>This report is <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>’s twenty-first annual review of human rightspractices around the globe. It summarizes key human rights issues in morethan 90 countries and territories worldwide, drawing on events throughNovember 2010.20

INTRODUCTIONEach country entry identifies significant human rights issues, examines thefreedom of local human rights defenders to conduct their work, and surveysthe response of key international actors, such as the United Nations, EuropeanUnion, Japan, the United States, and various regional and international organizationsand institutions.This report reflects extensive investigative work undertaken in 2010 by the<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> research staff, usually in close partnership with humanrights activists in the country in question. It also reflects the work of our advocacyteam, which monitors policy developments and strives to persuade governmentsand international institutions to curb abuses and promote humanrights. <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> publications, issued throughout the year, containmore detailed accounts of many of the issues addressed in the brief summariescollected in this volume. They can be found on the <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong><strong>Watch</strong> website, www.hrw.org.As in past years, this report does not include a chapter on every country where<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> works, nor does it discuss every issue of importance. Thefailure to include a particular country or issue often reflects no more thanstaffing limitations and should not be taken as commentary on the significanceof the problem. There are many serious human rights violations that<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> simply lacks the capacity to address.The factors we considered in determining the focus of our work in 2010 (andhence the content of this volume) include the number of people affected andthe severity of abuse, access to the country and the availability of informationabout it, the susceptibility of abusive forces to influence, and the importanceof addressing certain thematic concerns and of reinforcing the work of localrights organizations.The <strong>World</strong> <strong>Report</strong> does not have separate chapters addressing our thematicwork but instead incorporates such material directly into the country entries.21

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Please consult the <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> website for more detailed treatment ofour work on children’s rights, women’s rights, arms and military issues, businessand human rights, health and human rights, international justice, terrorismand counterterrorism, refugees and displaced people, and lesbian, gay,bisexual, and transgender people’s rights, and for information about our internationalfilm festivals.Kenneth Roth is executive director of <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>.22

WHOSE NEWS?Whose News?:The Changing Media Landscape and NGOsBy Carroll BogertThese are tough times for foreign correspondents. A combination of rapidtechnological change and economic recession has caused deep cuts in thebudget for foreign reporting at many Western news organizations. Plenty of exforeigncorrespondents have lost their jobs, and many others fear for theirjobs and their futures. Consumers of news, meanwhile, are watching internationalcoverage shrink in the pages of major papers. One recent study estimatedthat the number of foreign news stories published prominently in newspapersin the United Kingdom fell by 80 percent from 1979 to 2009. 1 TheOrganization for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that 20out of its 31 member states face declining newspaper readerships; 2 since foreignreporting is expensive, it is often the first to be cut.While changes in the media world may be hard on journalists and unsettlingfor news consumers, they also have very significant implications for internationalNGOs such as <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>. Foreign correspondents havealways been an important channel for international NGOs to get the word out,and a decline in global news coverage constitutes a threat to their effectiveness.At the same time, not all the implications of this change are bad. Theseare also days of opportunity for those in the business of spreading the word.This essay attempts to examine the perils and possibilities for internationalNGOs 3 in these tectonic shifts in media.Of course NGOs of all kinds accomplish a great deal without any recourse tothe media at all. <strong>Human</strong> rights activists pursue much of their mission outsidethe public eye: private meetings with diplomats; closed-door policy discussionswith government officials; strategy sessions with other NGOs; and, of23

WHOSE NEWS?<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> Council in Geneva, for example, government delegations conductextensive diplomatic campaigns to avoid being publicly censured.Bad publicity can help spark government action. When a video surfaced inOctober 2010 showing two Papuan farmers being tortured by Indonesian soldiers,the Indonesian government clearly felt pressure to act. United StatesPresident Barack Obama was scheduled for a visit that month and neither governmentwanted the torture issue to dominate the headlines. The Indonesiangovernment, which has been notoriously reluctant to punish its soldiers forhuman rights abuses, promptly tried and convicted four soldiers of torture. 4 Itwas clearly responding to media pressure in doing so.For groups that do not enjoy extensive grass-roots support or mass membership,media coverage may act as a kind of stand-in for public pressure. In veryfew countries, and relatively rare circumstances, does the public become seriouslymobilized over an issue of foreign policy. To be sure, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has the capacity to rally global publics outside theregion–on both sides–and so does the use of US military power abroad. TheSave Darfur campaign brought hundreds of thousands of students and othersupporters to street demonstrations. But those are exceptions. In general, foreignaffairs pique the interest of a narrow subsection in any society. Extensivemedia coverage of an issue may help to affect policy even when the publicremains silent on the issue. Serbian atrocities in Kosovo at the end of the1990’s comes to mind; significant public debate, in the media and elsewhere,helped generate pressure on NATO policymakers to take action.Media coverage can also act as an informal “stamp of approval” for internationaladvocacy groups. When a prominent publication cites an NGO official ina story, it signifies that the reporter, who is supposed to be knowledgeableabout the issue, has determined the NGO to be credible. When an NGOspokesperson appears on a well-regarded television show, she may thereafter25

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>carry greater weight with the policymakers she is trying to reach. Her veryaccess to the media megaphone makes her a bigger threat, and a person tobe reckoned with.If advocacy groups need the media, it is clear that media need them, too. Inmany countries where the press corps is not fully free, journalists rely on internationalgroups to say things that they cannot. In Bahrain, for example, theruling family promotes itself as reformist but it would have been very difficultfor the one independent local newspaper there to report extensively onrenewed use of torture during police interrogations. The fact of this resurgencewas widely alleged by activists and detainees, but considered too sensitive topublicize locally. 5 When <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> published a report on the issue, 5the local independent newspaper covered the issue extensively, reproducingmuch of the report in its pages without major fear of retribution.Foreign correspondents working in repressive countries do not face the sameconsequences that local journalists do when they report on human rights orsocial justice issues. But they, too, may pull their punches in order to avoidproblems with their visas or accreditation. Quoting an NGO making criticalcomments is safer than doing so oneself.Some journalists feel a strong bond of kinship with NGOs that work on politicalrepression and abuse of power. Whether it was Washington Post correspondentsBob Woodward and Carl Bernstein bringing the Watergate crimes tolight, or the international press corps covering the wars in the formerYugoslavia, journalists are often driven by the desire to expose the crimes ofpolitical leaders and see justice done.Whose Sky is Falling?Paradoxically, it is precisely in wealthier countries where the media are sickesttoday. In the United States, the triple blow of the internet, the economic reces-26

WHOSE NEWS?sion, and the poor management of a few major newspapers has dramaticallyshrunk the cadre of foreign correspondents. Several daily papers, such as theBoston Globe and Newsday, have shut down their foreign bureaus entirely.Television networks have closed almost all of their full-fledged bureaus, leavinglocal representatives in a handful of capitals. The New York Times and TheWashington Post, the reigning monarchs of international coverage, appear tomaintain their foreign bureaus more out of the personal commitment of thefamilies who still own them. In the United States, at least, the commercialmodel for international fact-gathering and distribution is evidently broken.No one is more vocal about the dire consequences of these cutbacks than thenewspapers’ foreign correspondents themselves. Pamela Constable, arespected foreign correspondent for The Washington Post, wrote in 2007: “Ifnewspapers stop covering the world, I fear we will end up with a microscopicelite reading Foreign Affairs and a numbed nation watching terrorist bombingsflash briefly among a barrage of commentary, crawls, and celebrity gossip.” 6As The New York Times’ chief foreign correspondent said: “When young menask me for advice on how to become a foreign correspondent, I tell them:‘Don’t.’ It is like becoming a blacksmith in 1919–still an honorable and skilledprofession; but the horse is doomed.” 7But the correspondent, C.L. Sulzberger, made that comment in 1969. Every agelaments its own passing, and old foreign correspondents are no exception. Itis not entirely clear that the American public, or the public in any of the countrieswhere foreign correspondents are in decline, is less well-informed than itused to be. At least one study has shown, in fact, that the American public isroughly as informed about international affairs as it was 20 years ago, beforethe big declines in traditional sources of foreign reporting. 8 And overall, evenamong Western publics, media consumption is increasing. 927

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Meanwhile, in countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, and others,the internet is allowing the public to get foreign news without government filters–animportant advance in their knowledge of the world. 10 And the OECDhas estimated that, while readership of newspapers is declining among mostof its members, that decline is more than offset by the overall growth in thenewspaper industry globally. 11A number of media outlets from the global South have greatly enhanced theirinternational presence in recent years. Al-Jazeera and al-Jazeera English,financed by the emir of Qatar, report on a wide range of global news, althoughthe network has recently cut back one of its four international broadcastingcenters. Others are not so free-wheeling. Xinhua, the state-run news agency ofChina, and other Chinese media organizations such as CCTV, are loathe to runmuch human rights news–and are positively allergic to such news out of Chinaor its allies.A Peril and a BoonThe information revolution made possible by the internet represents both aperil and a boon to international NGOs grappling with the decline in Westernmedia reporting on foreign news. On the one hand, the plethora of online publications,blogs, Facebook, and Twitter feeds, cable and satellite television stations,and other forms of new media is clamorous and confusing. How areadvocacy groups to know which media are important? If one purpose of gettingmedia coverage, as laid out above, is to reach policymakers, how doesone ascertain which media they are consuming? Previously, in most countries,a couple of daily papers, a weekly magazine or two, and a few radio and televisionbroadcasts constituted the core of what critical decision-makers in governmentwere likely to get their news from. Nowadays their reading habits arenot so easy to guess. The audience for international news has fractured.28

WHOSE NEWS?A 2008 study by graduate students at Columbia University asked a range ofofficials associated with the UN in New York what media they read, listened to,and watched. Unsurprisingly, nearly three-quarters of those surveyed said theyread The New York Times every day. Fifty percent read The Economist–also nosurprise. But a significant number of respondents said they were also readingthe frequent postings of a blogger at the Inner City Press, who covers UN affairsclosely but is virtually unknown outside the UN community. 12The internet poses the challenge of the glut. Advocacy groups, after all, notonly seek media coverage but also respond to media queries. Which questionersare worthy of the scarce attentions of an NGO? Which bloggers are merelycranks who will waste an inordinate amount of staff time while offering littleimpact? And how does one tell the difference? And how much time should anNGO spend poring through the latest data-dump from Wikileaks?But then there is the boon. The same internet that has blown a gaping hole inmedia budgets is also allowing NGOs to reach their audiences directly.Technologies that were once the exclusive preserve of a professional class arenow widely available. Taking a photograph of a policeman beating up ademonstrator and transmitting the image to a global audience used to involveexpensive equipment and access to scarce transmission technology. Only ahandful of trained journalists could do it. Now the same picture can be takenand transmitted with a US$35 mobile phone. During Egypt’s parliamentaryelections in late November 2010, for example, the government rejected internationalobservers and drastically restricted local monitors. But NGO activistsmanaged to film a local mayor affiliated with the ruling party filling out multipleballots and, in another place, plainclothes men with sticks disrupting apolling station.29

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Picking Up the Slack?For NGOs with large field presences–and even for those with only an occasionalinvestigator or representative overseas–the ability to generate and distributecontent is potentially revolutionary. But it requires more than taking a cellphonephotograph of a news event and posting it to Facebook. The question iswhether NGOs will operate systematically in the vacuum left by the commercialmedia. To do so will require re-purposing the information they are alreadygathering, and acquiring the skills to reach the public directly with featurescapable of attracting public attention. At present not many NGOs have theresources to reconfigure their research and information into user-friendly content.Most of them operate on the written word. Often they are addressingother experts rather than the public at large. Importantly, they generally haveprecious little visual information to illustrate their findings.That is beginning to change. <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> assigns professional photographers,videographers, and radio producers to work in the field alongsideits researchers, documenting in multimedia features what the researchers aredocumenting in words. 13Amnesty International is creating an autonomous “news unit,” staffed withfive professional journalists, to generate human rights news. Medecins SansFrontieres also uses photography and video extensively, while the NaturalResources Defense Council is assigning journalists to write about environmentalissues.Even if NGOs are able to produce user-friendly content, the question remainsof how to distribute it. An NGO can post content on its website, and reach afew thousand people, perhaps tens of thousands. Distributing via Facebook,Twitter, YouTube, and other social media might garner a few thousand more.Content that “goes viral” and reaches millions of people remains the rareexception. Sooner or later the question of distribution returns to the main-30

WHOSE NEWS?stream media, whose audiences still dwarf those of the non-profit sector. Willthey distribute content produced by NGOs?With budgets for foreign news in decline, one might expect editors and producersto be grateful for the offer of material from non-profit sources. But thatis not always the case, and the answer depends on the country, the mediaoutlet, and the NGO. The BBC, for example, rarely takes material from advocacygroups for broadcast. CBS, in the US, recently tightened up its regulationsfor taking content from outside sources. 14 Time magazine will not acceptimages from a photographer whose assignment was underwritten by an NGO.And many media commentators, writing on the rising importance of NGOs asinformation producers, are wary of the trend. “While journalists–if sometimesimperfectly–work on the principle of impartiality, the aid agency is usuallythere to get a message across: to raise money, to raise awareness, to change asituation.” 15Issues of Objectivity and NeutralityNGOs like <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong> do not present facts for the sake of reportingthe news but to inform the public and advocate on behalf of victims of abuse.That sets their work apart from traditional journalism and raises the veryimportant question of whether the information being gathered and conveyedby these NGOs is less trustworthy. Unless the NGO is transparent about itsaims, about the provenance of the material it is distributing, and about thestandards it uses in its own information-gathering, the consumer–whether ajournalist or a visitor to the website–will be justifiably wary.The best media professionals spend their entire careers trying, as hard as theycan, to rid their own reporting of bias and to be fair to all sides. They believe,and they are correct, that unbiased information is a genuine public good andthat biased information can mislead readers, including policymakers, into bad31

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>decisions–even social strife and violence. Many media training organizationsin conflict zones around the world are struggling to instill the notion of unbiasedreporting in media environments where the lack of it has proved disastrous.At the same time few people believe that the American media, wherethe culture of neutral and apolitical reporting has been most fiercely propagated,are in fact unbiased.Research-driven NGOs put a premium on rigorous, factual reporting. If theyplay fast and loose with the facts, they lose credibility and so lose tractionwith policymakers. Their reputations depend on objective reporting from thefield. At the same time, they work in service of a cause, advocating on behalfof victims and seeking accountability for perpetrators. While different NGOshave different standards for gathering, checking, and vetting information, theentire purpose of that information is to act to protect human dignity. Thosewho gather information must do so impartially, from all sides, but they are notneutral towards atrocity.Media organizations and advocacy groups stay independent of each other forgood reason. They are pursuing different objectives. Journalists’ refusal to distributecontent produced by others protects against the partisan abuse of themedia space. Meanwhile, international advocacy groups are wary of driftingfrom their core mission into the media business. But changes in technologyand commerce, at least in some countries, are pushing them closer together.To the extent that NGOs do produce more user-friendly content, they mustkeep in mind a few principles for establishing their credibility: first, transparencyin the methods of collecting the information; second, a proven trackrecord and a reputation, over many years, for reliable research; and third,complete openness about the aims of the organization and the fact of itsauthorship.32

WHOSE NEWS?NGOs still face the question of how far they want to go in creating user-friendlycontent. Few seem inclined to reorient their identities as information producersin the new information age. Filling the vacuum in international news takesmoney, and most NGOs struggle to meet their existing budgets, let aloneexpand into areas that seem tangential to their central mission. But if theyturn their backs on the trend, they will miss a critical opportunity to be heard.This information revolution has big implications for more than just a handfulof advocacy groups. Any entity that produces denser material written for amore specialist audience must now realize that the legions of those who willtransform it into something the layperson can understand–in other words, awork of journalism–are now much diminished. To have maximum impact inthe world today, information must be repurposed and refashioned for multipleaudiences and platforms, like a seed sprouting in every direction. That is atrend that no one who cares about influencing public opinion can afford toignore.Carroll Bogert is the deputy executive director, external relations,of <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>.33

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>1 Martin Moore, Shrinking <strong>World</strong>: The decline of international reporting in the Britishpress (London: Media Standards Trust, November 2010), p 17. The study looked at foreignstories appearing in the first ten pages of four major daily newspapers.2 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Directorate for Science,Technology and Industry Committee for Information, Computer, and CommunicationsPolicy, “The Evolution of News and the Internet,” June 11, 2010http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/30/24/45559596.pdf (accessed November 20, 2010),p.7. The steepest declines were registered in the United States, the United Kingdom,Greece, Italy, Canada, and Spain.3 This essay focuses primarily on NGOs that do research and advocacy in multiple countriesand therefore interact regularly with journalists who cover one country for audiencesin another. Most of these remarks concern NGOs working on human rights andother social justice issues, rather than, for example, global warming and the environment,although they face some of the same challenges.4 The four were actually convicted of torture that was revealed in another, unrelatedvideo. See “Indonesia: Investigate Torture Video From Papua,” <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>news release, October 20, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/10/20/indonesiainvestigate-torture-video-papua.5 <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>, Torture Redux: The Rivival of Physical Coercion duringInterrogations in Bahrain, February 8, 2010,http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/02/08/torture-redux6 Pamela Constable, “Demise of the Foreign Correspondent,” The Washington Post,February 18, 2007.7 John Maxwell Hamilton, Journalism’s roving eye: a history of American foreign reporting(Lousiana State University Press, 2010), p. 457.8 “Public Knowledge of Current Affairs Little Changed by News and InformationRevolutions: What Americans Know: 1989-2007,” The Pew Research Center for the People& the Press, April 15, 2007 http://people-press.org/report/319/public-knowledge-of-current-affairs-little-changed-by-news-and-information-revolutions(accessed November 29,2010).9 Richard Wray, “Media Consumption on the Increase,” The Guardian, April 19, 2010http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/apr/19/media-consumption-survey(accessed November 21, 2010).10 See, for example, the Temasek Review in Singapore; Malaysiakini and other onlineportals in Malaysia; numerous Vietnamese bloggers; and the Democratic Voice of Burmaand Mizzima, among others.34

WHOSE NEWS?11 OECD, 201012 “Mass Media and the UN: What the Advocacy Community Can Do to Shape DecisionMaking,” Columbia University School of International Public Affairs, May 2009, on file at<strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>. The respondents came from the UN Secretariat, various UN departmentswhose work touches on human rights, and diplomats representing 12 of the 15 UNSecurity Council members.13 Many photographers now raise money from foundations to partner with NGOs. Amongthe most active donors, for example, is the Open Society Institute’s DocumentaryPhotography Project: http://www.soros.org/initiatives/photography (accessedNovember 20, 2010); photographers at Magnum are increasingly willing to “partner…with select charitable organizations and provid[e] free or reduced rate access to theMagnum Photos archive,” http://magnumfoundation.org/core-programs.html (accessedNovember 20, 2010).14 Private conversation with CBS producer, October 2010.15 Glenda Cooper, “When lines between NGO and news organization blur,” NiemanJournalism Lab, December 21, 2009, http://www.niemanlab.org/2009/12/glenda-cooper-when-lines-between-ngo-and-news-organization-blur/(accessed November 20, 2010).35

WORLD REPORT <strong>2011</strong>Schools as Battlegrounds:Protecting Students, Teachers, and Schoolsfrom AttackBy Zama Coursen-Neff and Bede SheppardOf the 72 million primary school-age children not currently attending schoolworldwide, more than half—39 million—live in countries afflicted by armedconflict. In many of these countries, armed groups threaten and kill studentsand teachers and bomb and burn schools as tactics of the conflict. 1Government security forces use schools as bases for military operations, puttingstudents at risk and further undermining education.In southern Thailand, separatist insurgents have set fire to schools at least327 times since 2004, and government security forces occupied at least 79schools in 2010. In Colombia, hundreds of teachers active in trade unionshave been killed in the last decade, the perpetrators often pro-governmentparamilitaries and other parties to the ongoing conflict between the governmentand rebel forces. In northern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), therebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) has abducted large numbers of childrenfrom schools and taken revenge on villages believed to be aiding LRA defectorsby, among other things, looting and burning schools.“We warn you to leave your job as a teacher as soon as possible otherwise wewill cut the heads off your children and shall set fire to your daughter,” read athreatening letter from Taliban insurgents in Afghanistan, where betweenMarch and October 2010 20 schools were attacked using explosives or arson,and insurgents killed 126 students.While attacks on schools, teachers, and students in Afghanistan have perhapsbeen most vivid in the public eye—men on motorbikes spraying pupils withgunfire, girls doused with acid—intentional targeting of education is a far-36

SCHOOLS AS BATTLEGROUNDSreaching if underreported phenomenon. It is not limited to a few countries buta broader problem in the world’s armed conflicts. <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Watch</strong>researchers have documented attacks on students, teachers, and schools—and their consequences for education—in Afghanistan, Colombia, the DRC,India, Nepal, Burma, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Thailand. The UnitedNation’s Education, Science, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) reports thatattacks occurred in at least 31 countries from 2007 to 2009. 2While only a few non-state armed groups openly endorse such attacks, too littleis being done to document, publicize, and take steps to end them. Nor isthe negative impact of long-term occupation of schools by military forces fullyappreciated. Access to education is increasingly recognized as an importantpart of emergency humanitarian response, particularly during mass displacementand natural disasters. But protecting schools, teachers, and studentsfrom deliberate attack in areas of conflict is only now receiving greater attention.<strong>Human</strong>itarian aid groups increasingly are alert to the harm and lastingcosts of such attacks and human rights groups have begun to address them inthe context of protecting civilians in armed conflict and promoting economicand social rights, including the right to education.An effective response to attacks on education will require more focused policiesand action by concerned governments and a much stronger internationaleffort. Making students, teachers, and schools genuinely off limits to nonstatearmed groups and regular armies will require governments, oppositiongroups, and other organizations to implement strong measures that areenforced by rigorous monitoring, preventive interventions, rapid response toviolations, and accountability for violators of domestic and international law.37