FOTP 2013 Full Report

FOTP 2013 Full Report

FOTP 2013 Full Report

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

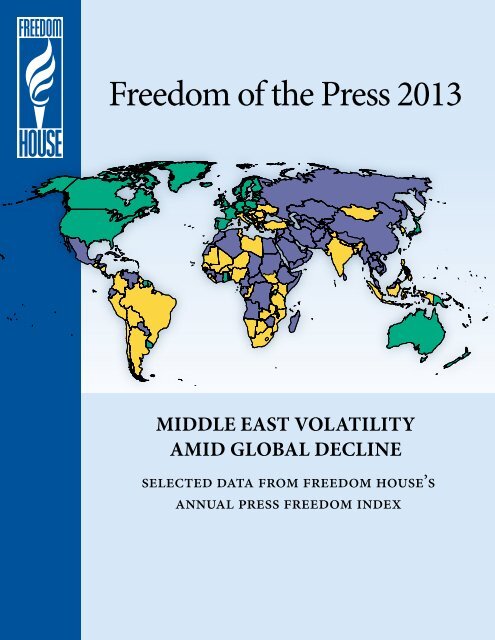

Freedom of the Press <strong>2013</strong>Middle East VolatilityAmid Global Declineselected data from freedom house’sannual press freedom index

AcknowledgementsFreedom of the Press <strong>2013</strong> could not have been completed without the contributions ofnumerous Freedom House staff and consultants. The section entitled “Contributors” contains adetailed list of writers and advisers without whose efforts this project would not have beenpossible.Karin Deutsch Karlekar served as the project director of Freedom of the Press <strong>2013</strong>. Extensiveresearch, editorial, analytical, and administrative assistance was provided by Jennifer Dunhamand Bret Nelson, as well as by Tyler Roylance, Morgan Huston, Zselyke Csaky, and AndrewRizzardi. Overall guidance for the project was provided by Arch Puddington, vice president forresearch, and Vanessa Tucker, vice president for analysis.We are grateful for the insights provided by those who served on this year’s expert review teams.In addition, the ratings and narratives were reviewed by a number of Freedom House staff basedin our Washington, D.C., and overseas offices, as well as by members of the InternationalFreedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) network. This report also reflects the findings of theFreedom House study Freedom in the World <strong>2013</strong>: The Annual Survey of Political Rights andCivil Liberties. Except where noted, statistics on internet usage were taken from the InternationalTelecommunications Union.The extensive work undertaken to produce Freedom of the Press <strong>2013</strong> was made possible by thegenerous support of the Leon Levy Foundation, the Jyllands-Posten Foundation, the HurfordFoundation and the Nicholas B. Ottaway Foundation. Freedom House also gratefullyacknowledges the contributions of Free Press Unlimited, Google, the Lilly Endowment, theLynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, and Freedom Forum.

Freedom of the Press ContributorsAnalysts:Ben Akoh is an expert on media and technology policy. He conducts research and undertakescapacity-building initiatives on internet public policy in Africa and globally, and is involved invarious capacities in national and regional internet-governance processes. He is an instructor atthe University of Manitoba, where his research explores the nexus of education, culture, and theinternet. Akoh also has been involved in various media-development initiatives in Africa. He hasworked with the Soros Foundation’s Open Society Initiative for West Africa, the UN EconomicCommission for Africa, the International Institute for Sustainable Development, and in theprivate sector. He served as a West Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Tehilla Shwartz Altshuler is a research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI), whereshe heads projects on media reform and open government. She holds an LLB and PhD from thelaw faculty at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and spent a postdoctoral year at the John F.Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. During 2011, Altshuler headed theresearch and development department of the Second Authority for Radio and Television, theIsraeli media regulator. Altshuler’s main academic interests are media and telecommunicationsregulation, and she has published and edited numerous articles, policy papers, and books onmatters of media and new media policy. She served as a Middle East and North Africa analystfor Freedom of the Press.Rozina Ali is a senior editor at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs, based in Egypt, and waspreviously an editor at the Economist Intelligence Unit. She received her master’s degree ininternational affairs from Columbia University, where she focused on Middle East studies, andher bachelor’s from Swarthmore College. She served as a Middle East and North Africa analystfor Freedom of the Press.Karen Attiah is a freelance journalist and has written for the Associated Press, the HuffingtonPost, and other outlets. She received her master’s degree in international affairs from ColumbiaUniversity’s School of International and Public Affairs, concentrating in human rights andinternational media. In 2008 Attiah was a Fulbright Scholar to Ghana, where she studied the roleof citizen participation in call-in radio shows during the Ghanaian elections, and has also studiedthe role of social media within African media organizations. She graduated from NorthwesternUniversity with a bachelor’s degree in communication studies and African studies. She served asa sub-Saharan Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Dawood Azami is a journalist who has worked for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)World Service in London for 14 years. He also worked as the BBC World Service bureau chiefand editor in Kabul, Afghanistan, in 2010 and 2011. Azami is a visiting lecturer at the Universityof Westminster, London, and specializes in international relations, conflict studies, and mediaand culture. He was selected as a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum in 2011,and in 2009 was the youngest person ever to win the BBC’s Global Reith Award for OutstandingContribution. He served as a South Asia analyst for Freedom of the Press.2

Anna Borshchevskaya is communications director at the American Islamic Congress and afellow at the European Foundation for Democracy, where she focuses on the former SovietUnion and the Middle East. Previously, she was assistant director at the Atlantic Council’sEurasia Center. She holds a master’s degree in international relations from the Johns HopkinsUniversity School of Advanced International Studies, and has published in the MediterraneanQuarterly, Turkish Policy Quarterly, and Middle East Quarterly, and at Washingtonpost.com,CNN.com, FoxNews.com, and Forbes.com. She regularly provides translation and analysis forthe Foreign Military Studies Office at Fort Leavenworth. She served as a Eurasia analyst forFreedom of the Press.Luis Manuel Botello is the senior director of special projects at the International Center forJournalists (ICFJ). He worked for 10 years as ICFJ’s Latin America program director andlaunched its International Journalism Network (IJNet), an online media-assistance news service.He has worked in more than 20 Latin American countries on issues related to digital mediainnovation, specialty reporting, press freedom, and ethics. He is a regular on-air media analyst atCNN Español, NTN24, and Al-Jazeera. He previously worked as a journalist for TelevisoraNacional in Panama. He was a Fulbright Scholar at Louisiana State University’s Manship Schoolof Mass Communication, where he received his master’s degree in mass communications. Heserved as a Central America analyst for Freedom of the Press.Lisa Brooten is an associate professor in the Department of Radio, Television and Digital Mediaat Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. Her research focuses on media reform anddemocratization, local and global social-movement media, community media, indigenous media,human rights, gender and militarization, and interpretive, critical research methods, particularlyin Southeast Asia, where she has lived and conducted fieldwork for many years. Currently, she iscompleting a comparison of media reform efforts in Thailand, the Philippines, and Burma fundedin the initial stages by a 2008 Fulbright Research Fellowship. She is also a member of theFulbright Specialist Roster for Burma/Myanmar, Thailand, and the Philippines. She served as aSoutheast Asia analyst for Freedom in the Press.Sarah Cook is a senior research analyst for East Asia at Freedom House. She manages the teamthat produces the China Media Bulletin, a biweekly news digest of press freedom developmentsrelated to China. She previously served as assistant editor of Freedom House’s Freedom on theNet index, which assesses internet and digital media freedom around the world. She coedited theEnglish version of Chinese attorney Gao Zhisheng’s memoir, A China More Just, and was adelegate to the UN Human Rights Commission for an organization working on religious freedomin China. She received a master’s degree in politics and a master of laws degree in publicinternational law from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, where she was aMarshall Scholar. She served as an East Asia analyst for Freedom of the Press.Zselyke Csaky is a research analyst for Nations in Transit, Freedom House’s annual report ondemocratic governance from Central Europe to Eurasia. She served previously as a researcher forFreedom of the Press. Prior to joining Freedom House, she worked for the Hungarian and U.S.offices of Amnesty International. She holds a master’s degree in international relations and3

European studies and a postgraduate degree in human rights from the Central EuropeanUniversity. She served as an Eastern and Western Europe analyst for Freedom of the Press.Melanie Dominski is a program manager at the Center for Peacebuilding in Sanski Most, Bosniaand Herzegovina, a local organization focused on reconciliation work, where she is responsiblefor fundraising efforts, as well as the monitoring and evaluation of all programs. Previously, sheserved as a program officer for the Global Freedom of Expression Campaign at Freedom House.She holds a master’s degree in international affairs, with a thematic concentration in humansecurity and development and a regional concentration in Europe and Eurasia, from the ElliottSchool of International Affairs at George Washington University. She served as an EasternEurope analyst for Freedom of the Press.Jennifer Dunham is a senior research analyst for Freedom in the World and Freedom of thePress at Freedom House. Previously, she was the managing editor and Africa writer for Facts OnFile World News Digest. She holds a bachelor’s degree in history-sociology from ColumbiaUniversity and a master’s degree in international relations from New York University, where shewrote her thesis on transitional justice in Rwanda and Sierra Leone. She served as a SouthernAfrica analyst for Freedom of the Press.Sarah Giaziri is the Middle East and North Africa program officer at the Rory Peck Trust. Thetrust supports freelance newsgatherers and their families worldwide in times of need, raises theirprofile, promotes their welfare and safety, and supports their right to report freely and withoutfear. Her areas of focus include Syria and Libya following the uprisings in both countries. Sheholds a degree in international relations, a master’s degree in human rights, and a postgraduatedegree in law. She practiced law for five years, focusing on human rights issues arising out ofextradition and international crime cases. She served as a Middle East and North Africa analystfor Freedom of the Press.Thomas W. Gold is the director of strategic initiatives and external affairs at the ResearchAlliance for New York City Schools at New York University. He is a former assistant professorof comparative politics at Sacred Heart University and the author of The Lega Nord andContemporary Politics in Italy. He received a PhD in political science from the New School forSocial Research and a Fulbright Fellowship to conduct research in Italy. He served as a WesternEurope analyst for Freedom of the Press.Sylvana Habdank-Kołaczkowska is the project director of Nations in Transit, FreedomHouse’s annual report on democratic governance from Central Europe to Eurasia. She also writesreports on Central Europe for the Freedom in the World report. Previously, she was themanaging editor of the Journal of Cold War Studies, a peer-reviewed quarterly. She holds amaster’s degree from Harvard University in regional studies of Eastern Europe and Eurasia, anda bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of California, Berkeley. She servedas a Central Europe analyst for Freedom of the Press.Summer Harlow is a PhD candidate in journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. AnInter-American Foundation Grassroots Development Fellow conducting her dissertation researchon the digital evolution of activist media in El Salvador, she is a journalist with more than 104

years of experience. She has reported and blogged from the United States and Latin America,covering immigration, city government, transportation, minority affairs, and press freedomissues. Her main research inquiries are related to the links between journalism and activism, withan emphasis on Latin America, digital media, alternative media, and internationalcommunication. She served as an Americas analyst for Freedom of the Press.Deborah Horan spent more than a decade covering the Middle East, including Iraq, Iran, Egypt,Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, as a correspondent for the Chicago Tribune and the HoustonChronicle. In 2002, she was a Knight Wallace Journalism Fellow at the University of Michigan,where she studied the rise of the satellite network Al-Jazeera. She joined the Tribune in 2002 andcovered the American Muslim immigrant community and the Iraq war in 2003 and 2004. She iscurrently based in Washington, DC, where she works as a freelance writer and consultant. Sheserved as a Middle East and North Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Sallie Hughes is an interdisciplinary communications scholar with a specialization in LatinAmerica, the Caribbean, and their diasporas. She is the coauthor of the book Making a Life inMulti-Ethnic Miami: Immigration and the Rise of a Global City and author of Newsrooms inConflict: Journalism and the Democratization of Mexico. She recently joined the editorial boardof the International Journal of Press/Politics and is the program track chair for mass media andpopular culture for the 2014 Congress of the Latin American Studies Association. She teachesgraduate and undergraduate courses in the Department of Journalism and Media Managementand the Latin American Studies Program at the University of Miami. She served as an Americasanalyst for Freedom of the Press.Michael Johnson holds a bachelor’s degree in political science–history from Rutgers Universityand a master’s degree in international affairs from the School of International Service atAmerican University. Prior to working at Freedom House, he had a one-year fellowship at theU.S. Department of Commerce in the Bureau of Industry and Security. His most recent researchhad examined China’s rise as a global power and its military modernization efforts. He served asan Asia-Pacific analyst for Freedom of the Press.Karin Deutsch Karlekar is project director of Freedom of the Press. She has conductedresearch and advocacy missions on press freedom, human rights, and governance issues to anumber of countries in Africa and South Asia, and has written reports for several Freedom Housepublications. In addition, she speaks and publishes widely on press freedom, new media, andmedia indicators, and developed the methodology for Freedom House’s Freedom on the Netindex. Currently, she also serves as a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global AgendaCouncil on Informed Societies. She holds a PhD in Indian history from Cambridge Universityand previously worked at the Economist Intelligence Unit and as a consultant for Human RightsWatch. She served as a South Asia and Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Mark A. Keller is deputy editor at the Latin Trade Group in Miami. His work focuses on thecompany’s market intelligence and research arm, providing insight into business, economic, andpolitical developments relevant to businesses operating in Latin America. Previously he workedas a research intern at Freedom House, and an editorial associate at Americas Society/Council ofthe Americas. He holds a master’s degree in Latin American studies from the University of5

Oxford, where his work focused on Brazil and the Southern Cone, and a bachelor’s degree inhistory from Columbia University. He served as an Americas analyst for Freedom of the Press.Alex Kendall is a manager at the international consultancy Global Health Strategies (GHS).Prior to joining GHS, she spent two years in Washington, DC, as the global health policy analystfor the Congressional Research Service, where she provided analysis on issues related to globalhealth, gender-based violence, and postconflict and disaster reconstruction efforts for membersof the House and Senate. She has also worked in the field on programs related to women’shealth, HIV/AIDS, sexual violence, human trafficking, and youth education in Haiti, Senegal,Rwanda, South Africa, and Cambodia. She holds a master’s degree in international relationsfrom Yale University. She served as a West Africa and Caribbean analyst for Freedom of thePress.Amy Killian is a master’s candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced InternationalStudies. Previously, she worked with the Liberty Institute of New Delhi, expanding theirEmpowering India initiative to improve transparency in Indian elections. She is a former staffmember of Freedom House and has worked on its Southeast Asia, exchanges, and advocacyprograms. Prior to joining Freedom House, she was a fellow with Kiva Microfunds in Cambodia.She served as a Southeast Asia analyst for Freedom of the Press.Andrew Konove received his PhD in history from Yale University in <strong>2013</strong>, with a concentrationin Latin American studies. His research focuses on politics, economics, and the development ofthe public sphere in Latin America. He conducted field research as a Fox Fellow at the Colegiode México in Mexico City from 2009 to 2010, and has studied in Brazil and Spain. His writinghas appeared in the National Interest and the blog Avenida América. Prior to pursuing his PhD,he worked at the Federal Trade Commission in Washington, DC, and Servicios FinancierosAlternativos, a microfinance institution in Oaxaca, Mexico. He served as an Americas analyst forFreedom of the Press.Holiday Dmitri Kumar is a researcher and journalist based in New York City. She previouslyserved as research director for Tony Snow at Fox News and as senior media manager at the CatoInstitute in Washington. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from NorthwesternUniversity’s Medill School of Journalism, a master’s in political sociology from the Universityof Chicago, and a master’s in international affairs from the New School University in New YorkCity. She served as an Asia-Pacific and a Central and Eastern Europe analyst for Freedom of thePress.Astrid Larson is the Language Center administrative director at the French Institute AllianceFrançaise. She holds a master’s degree in international affairs from the New School Universityand a bachelor’s degree from Smith College. She served as a Western Europe analyst forFreedom of the Press.Alexander Lupis is a journalist and human rights researcher. During the 1990s, he worked forthe International Organization for Migration, the Open Society Institute, Human Rights Watch,and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, focusing on human rights issues inthe former Yugoslavia. More recently, he worked as the Europe and Central Asia program6

coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists, focusing on the former Soviet republics,followed by a one-year fellowship in Moscow at the Russian Union of Journalists. He served as aEurasia analyst for Freedom of the Press.Ekaterina Lysova is a human rights lawyer who holds a PhD in law from Far Eastern StateUniversity. She spent five years working as a media lawyer for the Press Development Instituteand for the IREX Media Program in Vladivostok and Moscow. She was a full-time researcher atthe University of Cologne’s Institute for East European Law and a research consultant for theMoscow Media Policy & Law Institute, and recently graduated from Georgetown University’sSchool of Foreign Service. She served as a Eurasia analyst for Freedom of the Press.Katherin Machalek is a freelance researcher and analyst specializing in the South Caucasus.She previously worked on Freedom House’s Nations in Transit report, and has publishednumerous articles on the region. When she is not working as an analyst, she helps civil societyorganizations in Russia and Ukraine with information and communication issues for the GenevabasedHuman Rights Information and Documentation Systems (HURIDOCS). She holds amaster’s degree in political science from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Sheserved as a Caucasus analyst for Freedom of the Press.Eleanor Marchant is a PhD student at the Annenberg School for Communications at theUniversity of Pennsylvania, specializing in political communications and new technology inAfrica. She is also a research associate at the Center for Global Communication Studies, whereshe advises on African and transnational media research projects. Previously, she worked at theProgramme in Comparative Media Law and Policy at Oxford University, the MediaDevelopment Investment Fund, and the Media Institute in Nairobi, and as assistant editor forFreedom of the Press. She received a master’s degree in international relations from New YorkUniversity. She served as a West Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Roozbeh Mirebrahimi is an Iranian journalist and writer, and has worked as a reporter, politicaleditor, or columnist for several Iranian newspapers. He is a founder and editor in chief of aPersian-language magazine, Iran in the World, and has also written several books about Iran. In2006, he received the Hellman/Hammett International prize from Human Rights Watch, whichacknowledged his work and perseverance. He was named the first International Journalist inResidence at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism in 2007, and in 2010–11 he was avisiting scholar at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. He served as aMiddle East analyst for Freedom of the Press.Karina Mirochnik is a journalist and a researcher specializing in Latin American politics. Sheholds a master’s degree in international relations from New York University and a master’sdegree in communications from the University of Buenos Aires. She has worked as a producerand writer at VME Media, Dow Jones, and MTV News Latino, among other media outlets.Previously, she was a reporter and congressional correspondent in Argentina. She served as aSouth America analyst for Freedom of the Press.Peter G. Mwesige is executive director of the African Centre for Media Excellence (ACME) inKampala, Uganda. A holder of a PhD in mass communication from Indiana University and a7

master’s degree in journalism and mass communication from the American University in Cairo,he was until November 2007 the head of the Department of Mass Communication at Kampala’sMakerere University. He has previously worked as a reporter, news editor, political editor, andpolitical columnist, including positions as executive editor of the Daily Monitor and grouptraining editor of the Nation Media Group in Kampala. He served as an East Africa analyst forFreedom of the Press.Caroline Nellemann is an international consultant specializing in digital media anddemocratization. Previously she has worked for Freedom House, the Berkman Center for Internet& Society at Harvard University, the Danish Aid Agency, and the Danish Ministry for Science,Technology, and Innovation. She holds a master’s degree in international development fromRoskilde University, Denmark. She served as a Western Europe analyst for Freedom of thePress.Bret Nelson is a research analyst for Freedom in the World and Freedom of the Press atFreedom House. He holds a master’s degree in political science from Fordham University and amaster’s degree in Middle East studies from the Graduate Center, CUNY. He served as a MiddleEast and North Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Folu Ogundimu is a professor in the School of Journalism and the College of CommunicationArts and Sciences at Michigan State University (MSU), East Lansing. He is coeditor of Mediaand Democracy in Africa. He is a faculty excellence adviser for the College of CommunicationArts and Sciences and core faculty of the African Studies Center and the Center for AdvancedStudy of International Development. He has also served as a senior research associate forAfrobarometer and the Center for Democracy and Development, Ghana; a research associate forthe Globalization Research Center on Africa, UCLA; and a visiting professor at the University ofLagos, Nigeria. He served as a West Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Shannon O’Toole is an editor and writer at Facts On File World News Digest, where she coversEastern Europe, Russia, and the Balkans. She is also a contributor to Freedom House’s Freedomin the World report. She received a bachelor’s degree in history and anthropology from theUniversity of Missouri, Columbia. She served as a Central and Eastern Europe analyst forFreedom of the Press.Abha Parekh is a master’s candidate at Columbia University’s School of International andPublic Affairs. Previously, she was a research fellow at the Observer Research Foundation inMumbai, working on urban development and environmental protection issues. She has alsoworked with the UN Mission in Kosovo, the Clinton Foundation, the Centre for Civil Society inNew Delhi, and Freedom House, where she assisted in producing Freedom on the Net 2011. Sheserved as a South Asia analyst for Freedom of the Press.Arch Puddington is vice president for research at Freedom House and coeditor of Freedom inthe World. He has written widely on American foreign policy, race relations, organized labor,and the history of the Cold War. He is the author of Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold WarTriumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty and Lane Kirkland: Champion of AmericanLabor. He served as the United States analyst for Freedom of the Press.8

Mara Revkin is a JD candidate at Yale Law School and former Fulbright Fellow in Jordan andOman. She previously served as assistant director of the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Centerfor the Middle East and as a junior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.Her current research projects focus on constitutional design, informal Sharia courts, and theIslamization of customary law in North Sinai, where she conducted field research in August<strong>2013</strong>. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Foreign Affairs, the Atlantic, andForeign Policy. She served as a Middle East and North Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Tom Rhodes is a freelance journalist and East Africa representative for the Committee to ProtectJournalists. He is also the cofounder of South Sudan’s first independent newspaper, the JubaPost, and continues to support journalist training initiatives in the region. Holding a master’sdegree in African studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, he has residedand worked in the East Africa region for over seven years. He served as an East Africa analystfor Freedom of the Press.Andrew Rizzardi is a researcher with Freedom House working extensively on press freedomissues. He holds a master’s degree in international affairs from American University’s School ofInternational Studies. He served as an Americas, Asia-Pacific, and sub-Saharan Africa analystfor Freedom of the Press.David Robie is associate professor of journalism in the School of Communication Studies atNew Zealand’s Auckland University of Technology and director of the Pacific Media Centre. Heholds a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Technology, Sydney, and a PhD inhistory/politics from the University of the South Pacific, Fiji. He is founding editor of PacificJournalism Review and convener of Pacific Media Watch, and has written several books onPacific media, including Mekim Nius: South Pacific Media, Politics, and Education. He alsopublishes the media freedom blog Café Pacific. He served as an Asia-Pacific analyst forFreedom of the Press.Mark Y. Rosenberg is a senior Africa analyst at Eurasia Group, focusing on the SouthernAfrica region. Previously, he worked as a researcher at Freedom House and assistant editor ofFreedom in the World. His opinion articles have appeared in the New York Times, the JerusalemPost, and Business Day (South Africa), and his research has been cited by publications includingthe Economist and the Financial Times. He received a master’s degree and a PhD in politicalscience from the University of California, Berkeley, where he was a National ScienceFoundation Graduate Fellow. He served as a Southern Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Tyler Roylance is a staff editor at Freedom House and is involved in a number of itspublications. He holds a master’s degree in history from New York University. He served as aCentral and Eastern Europe analyst for Freedom of the Press.Laura Schneider is a PhD candidate at the Research Center for Media and Communication ofthe University of Hamburg, and a media freedom and social-media expert at the InternationalMedia Center Hamburg. She works as a freelance journalist for several German media outletsand has worked as a radio and newspaper reporter in Mexico. At the International Media Center9

Hamburg, she is the project coordinator of the Latin American Media Program. She also worksas a consultant for Deutsche Welle Academy and UNESCO. She completed her bachelor’s andmaster’s degrees in communication science, journalism, and Latin American studies at theUniversities of Hamburg, Guadalajara (Mexico), and Sydney. She served as a Western Europeanalyst for Freedom of the Press.Hyunjin Seo is assistant professor and Docking Young Faculty Scholar in the William AllenWhite School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Kansas. She haspublished research studies in the areas of digital media, international journalism, and strategiccommunication. Prior to receiving her PhD from Syracuse University, she was a foreign affairscorrespondent for South Korean and international media outlets. During that time, she traveledextensively to cover major international events including six-party talks on North Korea’snuclear issues and UN and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit meetings. She served asan Asia-Pacific analyst for Freedom of the Press.Janet Steele is an associate professor of journalism in the School of Media and Public Affairs atGeorge Washington University. She received her PhD in history from Johns Hopkins Universityand has taught courses on the theory and practice of journalism in Southeast and South Asia as aFulbright senior scholar and lecturer. Her book, Wars Within: The Story of Tempo, anIndependent Magazine in Soeharto’s Indonesia, focuses on Tempo magazine and its relationshipwith the politics and culture of New Order–era Indonesia. She served as a Southeast Asia analystfor Freedom of the Press.Nicole Stremlau is coordinator of the program in comparative media law and policy at theUniversity of Oxford, where she is also a research fellow in the Centre of Socio-Legal Studies.She holds a PhD from the London School of Economics in development studies. Her researchfocuses on media policy during and in the aftermath of guerrilla struggles in the Horn of Africa.She served as an East Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Kai Thaler is a PhD student in the Department of Government at Harvard University with afocus on comparative politics and international relations in Africa, Latin America, and theLusophone countries. He is an affiliated researcher of the Portuguese Institute of InternationalRelations and Security (IPRIS) and has been a consultant for Handicap International, aresearcher at the Centre for Social Science Research at the University of Cape Town, and aDGARQ/FLAD Research Fellow at the Portuguese national archives. He holds a master’s degreein sociology from the University of Cape Town and a bachelor’s degree in political science fromYale University. He served as a sub-Saharan Africa analyst for Freedom of the Press.Leigh Tomppert is an independent researcher specializing in gender, human rights, anddevelopment issues. She currently works with the UN Entity for Gender Equality and theEmpowerment of Women (UN Women) as a policy consultant in the Women’s EconomicEmpowerment Section. She previously coedited Freedom House’s Women’s Rights in the MiddleEast and North Africa publication and has also written for Freedom in the World. She receivedmaster’s degrees in comparative and cross-cultural research methods from the University ofSussex and in the social sciences from the University of Chicago. She served as an Americasanalyst for Freedom of the Press.10

Mai Truong is a staff editor and research analyst for Freedom on the Net at Freedom House.Previously, she was the editor in chief of the Yale Journal of International Affairs and worked asa research assistant for a Yale-based project that studied women’s rights to land and otherproperty in East Africa. She holds a bachelor’s degree in international studies–sociology fromthe University of California, San Diego, and a master’s degree in international relations from theJackson Institute for Global Affairs at Yale University. She served as an East Africa analyst forFreedom of the Press.Vanessa Tucker is vice president for analysis at Freedom House. She was previously the projectdirector of Countries at the Crossroads, Freedom House’s annual report on democraticgovernance in 70 strategically important countries around the world. Prior to joining FreedomHouse, she managed the Program on Intrastate Conflict at Harvard Kennedy School, and has alsoworked at the Kennedy School’s Women and Public Policy Program. She holds a bachelor’sdegree in international development from McGill University and a master’s degree ininternational relations from Yale University. She served as a Middle East and North Africaanalyst for Freedom of the Press.Jason Warner is a PhD candidate in African studies and government at Harvard University. Hehas worked or consulted for the UN Development Programme, the Nigerian Mission to theUnited Nations, and the U.S. Army. He has published on African affairs in outlets includingCNN, the Council on Foreign Relations, and UN Dispatch, as well as in various academicjournals. He received master’s degrees in government from Harvard University and in Africanstudies from Yale University. He served as a sub-Saharan Africa analyst for Freedom of thePress.Eliza B. Young is the publications coordinator for Physicians for Human Rights. She previouslyserved as a political analyst for the Emergency Preparedness and Response Unit at theInternational Rescue Committee (IRC) in New York. Prior to joining the IRC, she worked as aresearch analyst at Freedom House. She holds a master’s degree in international relations fromKing’s College London and a bachelor’s degree in European history from Columbia University.She served as a Western Europe analyst for Freedom of the Press.Ratings Review Advisers:Rosental Calmon Alves holds the Knight Chair in International Journalism and the UNESCOChair in Communication in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. He isalso the founding director of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas. He began hisacademic career in the United States in 1996 after 27 years as a professional journalist, includingseven years as a journalism professor in Brazil. He holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism fromthe Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and was the first Brazilian to be awarded with a NiemanFellowship to study at Harvard University. A board member of several national and internationalorganizations, he has been a frequent speaker and trainer as well as a consultant. He served as anAmericas adviser for Freedom of the Press.11

Dan Caspi is a professor and former chair of the Department of Communications Studies, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (2004–09). He is the founding chair of the IsraelCommunication Association and has previously filled several public roles, including member ofthe Committee on Public Broadcasting of the Ministry of Science, Culture and Sports, and boardmember of the Israeli Broadcasting Authority. He has written, coauthored, and coedited severalbooks, including Media and Ethnic Minorities in the Holy Land; Beyond the Mirror: The MediaMap in Israel; and The Palestinian Arab In/Outsiders: Media and Conflict in Israel. Currently hepublishes a weekly blog in Hebrew for Haaretz. He served as a Middle East and North Africaadviser for Freedom of the Press.John Dinges is the Godfrey Lowell Cabot Professor of Journalism at Columbia University and aformer correspondent in Latin America. He was awarded the Maria Moors Cabot gold medal in1992. His books include The Condor Years: How Pinochet and His Allies Brought Terrorism toThree Continents; Assassination on Embassy Row (with Saul Landau); and Our Man in Panama:The Shrewd Rise and Brutal Fall of Manuel Noriega. He was an assistant editor on theWashington Post’s foreign desk; served as deputy foreign editor, managing editor, and editorialdirector of NPR News; and was founder/director of the Centro de Investigación e InformaciónPeriodística (CIPER) in Chile. He served as an Americas adviser for Freedom of the Press.Matt J. Duffy studies journalism in the Arab world with a focus on the government regulation ofboth traditional and digital media. His book on media laws of the United Arab Emirates will bepublished in early 2014. His other research has appeared in the Journal of Middle East Media,Middle East Media Educator, and the Journal of Mass Media Ethics. He teaches internationalcommunication law at Kennesaw State University and serves as a fellow with the Center forInternational Media Education at Georgia State University. He is also a member of the board ofdirectors for the Arab-U.S. Association for Communication Educators. He served as a MiddleEast and North Africa adviser for Freedom of the Press.Ashley Esarey received his PhD in political science from Columbia University and held the AnWang Postdoctoral Fellowship at Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. He teachesEast Asian studies and political science at the University of Alberta and is an associate inresearch at the University of Alberta’s China Institute. His publications concern propaganda andinformation control in China and the impact of digital communication on Chinese politics. He iscoeditor of The Internet in China and coauthor of My Fight for a New Taiwan: One Woman’sJourney from Prison to Power. He is currently working on a book comparing regime change(and the lack thereof) in China, Taiwan, Libya, and Tunisia. He served as an Asia-Pacific adviserfor Freedom of the Press.Howard W. French is an associate professor at the Columbia University Graduate School ofJournalism, where he has taught since 2008. He previously was a senior writer for the New YorkTimes, where he spent most of his career as a foreign correspondent, including serving as chief ofthe Times’s Shanghai bureau and heading bureaus in Japan, West and Central Africa, CentralAmerica, and the Caribbean. His work for the newspaper in both Africa and China wasnominated for the Pulitzer Prize. He is the author of A Continent for the Taking: The Tragedyand Hope of Africa, which was named nonfiction book of the year by severalnewspapers. Disappearing Shanghai, French’s documentary photography of the last remnants of12

Shanghai’s historic neighborhoods, has been featured in numerous exhibitions and magazines, aswell as a book. He served as a sub-Saharan Africa adviser for Freedom of the Press.Jeffrey Ghannam is an attorney and media professional who has contributed widely to theanalysis and debate about the role of digital media leading up to and following the recent civilmovements in the Arab world, including a two-part report for the National Endowment forDemocracy’s Center for International Media Assistance. He has written separately on the subjectfor the Economist and the Washington Post. He received a Knight International JournalismFellowship to Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon to develop programs in the region,where he has also served as a media development trainer and adviser. He spent a decade at theDetroit Free Press, where he reported on the law and served as an editor. He was on staff at theNew York Times Washington bureau and contributed news and features. He served as a MiddleEast and North Africa adviser for Freedom of the Press.Peter Gross is director of the School of Journalism and Electronic Media at the University ofTennessee, Knoxville. His scholarly specialization is in international communication, with afocus on Central and Eastern Europe. He was instrumental in establishing a new journalismprogram in 1992 at the University of Timisoara, Romania, and in the last 24 years served as aconsultant for the International Media Fund, the Freedom Forum, and the Eurasia Foundation,and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, among other organizations. He is the author of EntangledEvolutions: Media and Democratization in Eastern Europe, as well as five other scholarly booksand three textbooks, and is the coeditor of two books, including Media Transformations in thePost-Communist World: Eastern Europe’s Tortured Path to Change. He served as a Central andEastern Europe/Eurasia adviser for Freedom of the Press.Daniel C. Hallin is a professor of communication at the University of California, San Diego. Hisbooks include The “Uncensored War”: The Media and Vietnam; We Keep America on Top ofthe World: Television Journalism and the Public Sphere; and, with Paolo Mancini, ComparingMedia Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics and Comparing Media Systems Beyond theWestern World. He has also written on media and politics in Mexico and on media and politicalclientelism in Latin America. He served as an Americas adviser for Freedom of the Press.Drew McDaniel is a professor and director of the School of Media Arts and Studies at OhioUniversity. He serves as honorary consultant at the Asia-Pacific Institute for BroadcastingDevelopment. He has authored a number of books, including Electronic Tigers of SoutheastAsia: The Politics of Media, Technology, and National Development and Broadcasting in theMalay World. He served as an Asia-Pacific adviser for Freedom of the Press.Kavita Menon is a senior program officer at the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). As CPJAsia program coordinator from 1999 to 2003, she led research and advocacy missions tocountries including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. She left CPJ to take up thePew Fellowship in international reporting at Johns Hopkins University’s School of AdvancedInternational Studies, and then worked as a researcher and campaigner on South Asia forAmnesty International before returning to CPJ in 2008. She has written for publicationsincluding the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, the International Herald Tribune, and Ms.magazine. She has produced radio features for NPR’s All Things Considered, Monitor Radio,13

WNYC, and WBAI, and previously worked as assistant producer of NPR’s On the Media. Sheearned a master’s degree from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. Sheserved as an Asia-Pacific adviser for Freedom of the Press.Devra C. Moehler is assistant professor at the Annenberg School of Communication, Universityof Pennsylvania. She holds a PhD in political science from the University of Michigan. Herresearch focuses on comparative political communication, democratization, partisan informationsources, and political behavior, with a focus on Africa. She is the author of the book DistrustingDemocrats: Outcomes of Participatory Constitution Making. Previously, she was an assistantprofessor of government at Cornell University and a fellow at the Harvard Academy ofInternational and Area Studies. In addition, she served as a Democracy Fellow at the U.S.Agency for International Development, where she provided technical assistance in the design ofexperimental and quasi-experimental impact evaluations of democracy and governanceassistance programs. She served as a sub-Saharan Africa adviser for Freedom of the Press.Robert Orttung is assistant director of the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studiesat George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs, president of theResource Security Institute, and a visiting scholar at the Center for Security Studies at the SwissFederal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich. He is managing editor of Demokratizatsiya:The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization and a coeditor of the Russian Analytical Digest andthe Caucasus Analytical Digest. He received a PhD in political science from the University ofCalifornia, Los Angeles. He served as a Central and Eastern Europe/Eurasia adviser for Freedomof the Press.Bettina Peters is director of development at the Thomson Foundation, a leader in internationalmedia support, journalism, and management training since 1962. Before joining the ThomsonFoundation, she was the director of the Global Forum for Media Development (GFMD), anetwork of organizations involved in media assistance programs around the world. Until 2007,she worked as director of programs at the European Journalism Center (EJC), in charge of itsinternational journalism training program. Previously, she worked for 11 years at theInternational Federation of Journalists headquarters in Brussels. She holds degrees in politicalscience and journalism from the University of Hamburg, and has edited several publications onjournalism, such as the GFMD’s Media Matters II and the EJC’s handbook on civic journalism.She served as a Western Europe adviser for Freedom of the Press.Lawrence Pintak is the founding dean of the Edward R. Murrow College of Communication atWashington State University (WSU). An award-winning former CBS News Middle Eastcorrespondent, he is the author of The New Arab Journalist and several other books onAmerica’s relationship with the Muslim world and the role of the media in shaping globalperceptions and government policy. Prior to WSU, he served as director of the Kamal AdhamCenter for Journalism Training and Research at the American University in Cairo. His workregularly appears in outlets including the New York Times, ForeignPolicy.com, and CNN.com,and he is frequently interviewed by international media. Pintak holds a PhD in Islamic studiesfrom the University of Wales. He served as a Middle East and North Africa adviser for Freedomof the Press.14

Richard Shafer is a professor of journalism at the University of North Dakota. His researchfocuses on the press and social change in developing nations, with a concentration in recent yearson the development of the press in post-Soviet Central Asia and the Caucasus. His most recentbook, coauthored with Eric Freedman, is After the Czars and Commissars: Journalism inAuthoritarian Post-Soviet Central Asia. Other published work includes over 50 peer-reviewedjournal articles. Since the late 1980s he has had seven international postings supported by severalfoundations and government agencies. He received his PhD from the University of Missouri,Columbia, in rural sociology with a minor in journalism. He served as a Central and EasternEurope/Eurasia adviser for Freedom of the Press.Wisdom J. Tettey is a professor and dean of the Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies at theUniversity of British Columbia, Canada. His research expertise and interests are in the areas ofmass media and politics in Africa; information and communications technologies (ICTs), civicengagement, and transnational citizenship; and the political economy of globalization and ICTs.Among his numerous publications are Media and Information Literacy, Informed Citizenship,and Democratic Development in Africa: A Handbook for Information/Media Producers andUsers; The Public Sphere and the Politics of Survival: Voice, Sustainability, and Public Policy inGhana; and African Media and the Digital Public Sphere. He has served as a consultant tovarious international organizations and recently coordinated a workshop for the African CapacityBuilding Foundation on “Information/Media Literacy, Informed Citizenship, and Africa’sDevelopment Agenda.” He served as a sub-Saharan Africa adviser for Freedom of the Press.Tudor Vlad is associate director of the James M. Cox Jr. Center for International MassCommunication Training and Research at the University of Georgia. He holds a PhD from theBabes-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, and a bachelor’s degree from the Universityof Bucharest. He has been a consultant for the New York Times, the Russian Journalists’ Union,and a Gallup World Poll senior research adviser. He has done research and written on mediasystems in emerging democracies, assessment of press freedom indicators, evaluation ofinternational media assistance programs, and journalism and mass communication curriculums.He served as Central and Eastern Europe/Eurasia adviser for Freedom of the Press.Peter VonDoepp is an associate professor of political science at the University of Vermont. Hisresearch focuses on African politics with specific attention to democratization issues. His mostrecent book, Judicial Politics in New Democracies: Cases from Southern Africa, examinesjudicial development in new Southern African democracies. His other published work appears ina variety of peer-reviewed journals and several edited volumes. His research has been supportedby the National Science Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, and the Fulbright-Hays program. Hereceived his PhD from the University of Florida. He served as a sub-Saharan Africa adviser forFreedom of the Press.David Ndirangu Wachanga is a professor of journalism at the University of Wisconsin,Whitewater. He holds a PhD in information science from the University of North Texas. He haswritten on emerging technologies and message propagation, global information flow, and the useof communication technologies in restrictive information and economic environments. He hasappeared on Voice of America (VOA) and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) todiscuss media, technology, diasporas, and globalization. He is conducting research on the15

MethodologyThe <strong>2013</strong> index, which provides analytical reports and numerical ratings for 197 countries andterritories, continues a process conducted since 1980 by Freedom House. The findings are widelyused by governments, international organizations, academics, activists, and the news media inmany countries. Countries are given a total score from 0 (best) to 100 (worst) on the basis of a setof 23 methodology questions divided into three subcategories. Assigning numerical points allowsfor comparative analysis among the countries surveyed and facilitates an examination of trendsover time. The degree to which each country permits the free flow of news and informationdetermines the classification of its media as “Free,” “Partly Free,” or “Not Free.” Countriesscoring 0 to 30 are regarded as having “Free” media; 31 to 60, “Partly Free” media; and 61 to100, “Not Free” media. The criteria for such judgments and the arithmetic scheme for displayingthe judgments are described in the following section. The ratings and reports included in Freedomof the Press <strong>2013</strong> cover events that took place between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2012.CriteriaThis study is based on universal criteria. The starting point is the smallest, most universal unit ofconcern: the individual. We recognize cultural differences, diverse national interests, and varyinglevels of economic development. Yet Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rightsstates:Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includesfreedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impartinformation and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers.The operative word for this index is “everyone.” All states, from the most democratic tothe most authoritarian, are committed to this doctrine through the UN system. To deny thatdoctrine is to deny the universality of information freedom—a basic human right. We recognizethat cultural distinctions or economic underdevelopment may limit the volume of news flowswithin a country, but these and other arguments are not acceptable explanations for outrightcentralized control of the content of news and information. Some poor countries allow for theexchange of diverse views, while some economically developed countries restrict contentdiversity. We seek to recognize press freedom wherever it exists, in poor and rich countries aswell as in countries of various ethnic, religious, and cultural backgrounds.Research and Ratings Review ProcessThe findings are reached after a multilayered process of analysis and evaluation by a team ofregional experts and scholars. Although there is an element of subjectivity inherent in the indexfindings, the ratings process emphasizes intellectual rigor and balanced and unbiased judgments.The research and ratings process involves several dozen analysts—including members ofthe core research team headquartered in New York, along with outside consultants—whoprepared the draft ratings and country reports. Their conclusions are reached after gatheringinformation from professional contacts in a variety of countries, staff and consultant travel,international visitors, the findings of human rights and press freedom organizations, specialists ingeographic and geopolitical areas, the reports of governments and multilateral bodies, and avariety of domestic and international news media. We would particularly like to thank the othermembers of the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) network for providing17

detailed and timely analyses of press freedom violations in a variety of countries worldwide onwhich we rely to make our judgments.The ratings are reviewed individually and on a comparative basis in a set of six regionalmeetings involving analysts, advisers, and Freedom House staff. The ratings are compared withthe previous year’s findings, and any major proposed numerical shifts or category changes aresubjected to more intensive scrutiny. These reviews are followed by cross-regional assessments inwhich efforts are made to ensure comparability and consistency in the findings.MethodologyThrough the years, we have refined and expanded our methodology. Recent changes are intendedto simplify the presentation of information without altering the comparability of data for a givencountry over the 32-year span or the comparative ratings of all countries over that period.Our examination of the level of press freedom in each country currently comprises 23methodology questions and 109 indicators divided into three broad categories: the legalenvironment, the political environment, and the economic environment. For each methodologyquestion, a lower number of points is allotted for a more free situation, while a higher number ofpoints is allotted for a less free environment. Each country is rated in these three categories, withthe higher numbers indicating less freedom. A country’s final score is based on the total of thethree categories: A score of 0 to 30 places the country in the Free press group; 31 to 60 in thePartly Free press group; and 61 to 100 in the Not Free press group.The diverse nature of the methodology questions seeks to encompass the varied ways inwhich pressure can be placed upon the flow of information and the ability of print, broadcast, andinternet-based media and journalists to operate freely and without fear of repercussions: In short,we seek to provide a picture of the entire “enabling environment” in which the media in eachcountry operate. We also seek to assess the degree of news and information diversity available tothe public in any given country, from either local or transnational sources.The legal environment category encompasses an examination of both the laws andregulations that could influence media content and the government’s inclination to use these lawsand legal institutions to restrict the media’s ability to operate. We assess the positive impact oflegal and constitutional guarantees for freedom of expression; the potentially negative aspects ofsecurity legislation, the penal code, and other criminal statutes; penalties for libel and defamation;the existence of and ability to use freedom of information legislation; the independence of thejudiciary and of official media regulatory bodies; registration requirements for both media outletsand journalists; and the ability of journalists’ groups to operate freely.Under the political environment category, we evaluate the degree of political controlover the content of news media. Issues examined include the editorial independence of both stateownedand privately owned media; access to information and sources; official censorship andself-censorship; the vibrancy of the media and the diversity of news available within eachcountry; the ability of both foreign and local reporters to cover the news freely and withoutharassment; and the intimidation of journalists by the state or other actors, including arbitrarydetention and imprisonment, violent assaults, and other threats.Our third category examines the economic environment for the media. This includes thestructure of media ownership; transparency and concentration of ownership; the costs ofestablishing media as well as any impediments to news production and distribution; the selectivewithholding of advertising or subsidies by the state or other actors; the impact of corruption andbribery on content; and the extent to which the economic situation in a country impacts thedevelopment and sustainability of the media.18

CHECKLIST OF METHODOLOGY QUESTIONS <strong>2013</strong>-- Each country is ranked on a scale of 0 to 100, with 0 being the best and 100 being the worst.-- A combined score of 0-30=Free, 31-60=Partly Free, 61-100=Not Free.-- Under each question, a lower number of points is allotted for a more free situation, while a higher number ofpoints is allotted for a less free environment.-- The sub-questions listed are meant to provide guidance as to what issues are meant to be addressed under eachmethodology question; it is not intended that the author necessarily answer each one.-- As a general guideline, the index is focused on ability to access news and information (which predominantlymeans print and broadcast media but can also including blogs, social media, and other forms of digital newsdissemination) and providers of news content, which predominantly means journalists but can also include citizenjournalists and bloggers, where applicable.A. LEGAL ENVIRONMENT (0-30 POINTS)1. Do the constitution or other basic laws contain provisions designed to protect freedom ofthe press and of expression, and are they enforced? (0-6 points)• Does the constitution contain language that provides for freedom of speech and of the press?• Do the Supreme Court, Attorney General, and other representatives of the higher judiciarysupport these rights?• Does the judiciary obstruct the implementation of laws designed to uphold these freedoms?• Do other high-ranking state or government representatives uphold protections for media freedom,or do they contribute to a hostile environment for the press?• Are crimes that threaten press freedom prosecuted vigorously by authorities?• Is there implicit impunity for those who commit crimes against journalists?2. Do the penal code, security laws, or any other laws restrict reporting and are journalistsor bloggers punished under these laws? (0-6 points)• Are there restrictive press laws?• Do laws restrict reporting on ethnic or religious issues, national security, or other sensitive topics?• Are penalties for ‘irresponsible journalism’ applied widely?• Are restrictions of media freedom closely defined, narrowly circumscribed, and proportional tothe legitimate aim?• Do the authorities restrict or otherwise impede legitimate press coverage in the name of nationalsecurity interests?• Are journalists regularly prosecuted or jailed as a result of what they write?• Are writers, commentators, or bloggers subject to imprisonment or other legal sanction as a resultof accessing or posting material on the internet?• Is there excessive pressure on journalists to reveal sources, resulting in punishments such as jailsentences, fines, or contempt of court charges?19

3. Are there penalties for libeling officials or the state and are they enforced? (0-3 points)• Are public officials especially protected under insult or defamation laws?• Are insult laws routinely used to shield officials’ conduct from public scrutiny?• Is truth a defense to libel?• Is there a legally mandated ‘right of reply’ that overrides independent editorial control?• Is libel made a criminal rather than a civil offense?• Are journalists or bloggers regularly prosecuted and jailed for libel or defamation?• Are fines routinely imposed on journalists or media outlets in civil libel cases in a partisan orprejudicial manner, with the intention of bankrupting the media outlet or deterring futurecriticism?4. Is the judiciary independent and do courts judge cases concerning the mediaimpartially? (0-3 points)• Are members of the judiciary subject to excessive pressure from the executive branch?• Are the rights to freedom of expression and information recognized as important among membersof the judiciary?• When judging cases concerning the media, do authorities act in a lawful and non-arbitrarymanner on the basis of objective criteria?• Is there improper use of legal action or summonses against journalists or media outlets (e.g. beingsubjected to false charges, arbitrary tax audits etc.)?5. Is Freedom of Information legislation in place and are journalists able to make use of it?(0-2 points)• Are there laws guaranteeing access to government records and information?• Are restrictions to the right of access to information expressly and narrowly defined?• Are journalists able to secure public records through clear administrative procedures in a timelymanner and at a reasonable cost?• Are public officials subject to prosecution if they illegally refuse to disclose state documents?6. Can individuals or business entities legally establish and operate private media outletswithout undue interference? (0-4 points)• Are registration requirements to publish a newspaper or periodical unduly onerous or are theyapproved/rejected on partisan or prejudicial grounds?• Is the process of licensing private broadcasters and assigning frequencies open, objective andfair?• Is there an independent regulatory body responsible for awarding licenses and distributingfrequencies or does the state control the allocations process?• Does the state place extensive legal controls over the establishment of internet web sites andISPs?• Do state or publicly-funded media receive preferential legal treatment?• Are non-profit community broadcasters given distinct legal status?• Is there substantial media cross ownership and is cross-ownership of media encouraged by theabsence of legal restrictions?• Are laws regulating media ownership impartially implemented?20

7. Are media regulatory bodies, such as a broadcasting authority or national press orcommunications council, able to operate freely and independently? (0-2 points)• Are there explicit legal guarantees protecting the independence and autonomy of any regulatorybody from either political or commercial interference?• Does the state or any other interest exercise undue influence over regulatory bodies throughappointments or financial pressure?• Is the appointments process to such bodies transparent and representative of different interests,and do representatives from the media have an adequate presence on such bodies?• Are decisions taken by the regulatory body seen to be fair and apolitical?• Are efforts by journalists and media outlets to establish self-regulatory mechanisms permitted andencouraged, and viewed as a preferable alternative to state-imposed regulation?8. Is there freedom to become a journalist and to practice journalism, and can professionalgroups freely support journalists’ rights and interests? (0-4 points)• Are journalists required by law to be licensed and if so, is the licensing process conducted fairlyand at reasonable cost?• Must a journalist become a member of a particular union or professional organization in order towork legally?• Must journalists have attended a particular school or have certain qualifications in order topractice journalism?• Are visas for journalists to travel abroad delayed or denied based on the individual’s reporting orprofessional affiliation?• May journalists and editors freely join associations to protect their interests and express theirprofessional views?• Are independent journalists’ organizations able to operate freely and comment on threats to orviolations of press freedom?B. POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT (0-40 POINTS)1. To what extent are media outlets’ news and information content determined by thegovernment or a particular partisan interest? (0-10 points)• To what degree are print and broadcast journalists subject to editorial direction or pressure fromthe authorities or from private owners?• Do media outlets—either print, broadcast, or internet–based—that express independent, balancedviews exist?• Is media coverage excessively partisan, with the majority of outlets consistently taking either apro- or anti-government line?• Is there government editorial control of state-run media outlets?• Does the government attempt to influence or manipulate online content?• Is there opposition access to state-owned media, particularly during elections campaigns? Dooutlets reflect the views of the entire political spectrum or do they provide only an official pointof view?• Is hiring, promotion, and firing of journalists in the state-owned media done in a non-partisanand impartial manner?• Is there provision for public-service broadcasting that enjoys editorial independence?21

2. Is access to official or unofficial sources generally controlled? (0-2 points)• Are the activities of government—courts, legislature, officials, records—open to the press?• Is there a ‘culture of secrecy’ among public officials that limits their willingness to provideinformation to media?• Do media outlets have a sufficient level of access to information and is this right equally enforcedfor all journalists regardless of their media outlet’s editorial line?• Does the regime influence access to unofficial sources (parties, unions, religious groups, etc.),particularly those that provide opposition viewpoints?3. Is there official or unofficial censorship? (0-4 points)• Is there an official censorship body?• Are print publications or broadcast programs subject to pre-or post-publication censorship?• Are local print and broadcast outlets forcibly closed or taken off the air as a result of what theypublish or broadcast?• Are there shutdowns or blocking of internet sites or blogs?• Is access to foreign newspapers, TV or radio broadcasts, websites, or blogs censored or otherwiserestricted?• Are certain contentious issues, such as official corruption, the role of the armed forces or thepolitical opposition, human rights, religion, officially off-limits to the media?• Do authorities issue official guidelines or directives on coverage to media outlets?4. Do journalists practice self-censorship? (0-4 points)• Is there widespread self-censorship in the state-owned media? In the privately owned media?• Are there unspoken ‘rules’ that prevent a journalist from pursuing certain stories?• Is there avoidance of subjects that can clearly lead to censorship or harm to the journalist or theinstitution?• Is there censorship or excessive interference of journalists’ stories by editors or managers?• Are there restrictions on coverage by ‘gentlemen’s agreement,’ club-like associations betweenjournalists and officials, or traditions in the culture that restrict certain kinds of reporting?5. Do people have access to media coverage and a range of news and information that isrobust and reflects a diversity of viewpoints? (0-4 points)• Does the public have access to a diverse selection of print, broadcast, and internet-based sourcesof information that represent a range of political and social viewpoints?• Are people able to access a range of local and international news sources despite efforts to restrictthe flow of information?• Do media outlets represent diverse interests within society, for example through community radioor other locally-focused news content?• Do providers of news content cover political developments and provide scrutiny of governmentpolicies or actions by other powerful societal actors?• Is there a tradition of vibrant coverage of potentially sensitive issues?• Do journalists or bloggers pursue investigative news stories on issues such as corruption by thegovernment or other powerful societal actors?6. Are both local and foreign journalists able to cover the news freely in terms ofharassment and physical access? (0-6 points)22

• Are journalists harassed while covering the news?• Are certain geographical areas of the country off-limits to journalists?• Does a war, insurgency, or similar situation in a country inhibit the operation of media?• Is there surveillance of foreign journalists working in the country?• Are foreign journalists inhibited or barred by the need to secure visas or permits to report or totravel within the country?• Are foreign journalists deported for reporting that challenges the regime or other powerfulinterests?7. Are journalists, bloggers, or media outlets subject to extralegal intimidation or physicalviolence by state authorities or any other actor? (0-10 points)• Are journalists or bloggers subject to murder, injury, harassment, threats, abduction, expulsion,arbitrary arrest and illegal detention, or torture?• Do armed militias, organized crime, insurgent groups, political or religious extremists, or otherorganizations regularly target journalists?• Have journalists fled the country or gone into hiding to avoid such action?• Have media companies been targeted for physical attack or for the confiscation or destruction ofproperty?• Are there technical attacks on news and information websites or key online outlets forinformation exchange?C. ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT (0-30 POINTS)1. To what extent are media owned or controlled by the government and does thisinfluence their diversity of views? (0-6 points)• Does the state dominate the country’s information system?• Are there independent or opposition print media outlets?• Does a state monopoly of TV or radio exist?• Are there privately owned news radio stations that broadcast substantial, serious news reports?• Do independent news agencies provide news for print and broadcast media?• In the case of state-run or funded outlets, are they run with editorial independence and do theyprovide a range a diverse, non-partisan viewpoints?• NOTE: This question is usually scored to provide 0-2 points each for print, radio and TV forms ofnews media.2. Is media ownership transparent, thus allowing consumers to judge the impartiality ofthe news? (0-3 points)• Is it possible to ascertain the ownership structure of private media outlets?• Do media owners hold official positions in the government or in political parties, and are theselinks intentionally concealed from the public?• Are privately owned media seen to promote principles of public interest, diversity and plurality?3. Is media ownership highly concentrated and does it influence diversity of content? (0-3points)23

• Are publications or broadcast systems owned or controlled by industrial or commercialenterprises, or other powerful societal actors, whose influence and financial power lead toconcentration of ownership of the media and/or narrow control of the content of the media?• Is there an excessive concentration of media ownership in the hands of private interests who arelinked to state patronage or that of other powerful societal actors?• Are there media monopolies, significant vertical integration (control over all aspects of newsproduction and distribution), or substantial cross-ownership?• Does the state actively implement laws concerning concentration, monopolies, and crossownership?4. Are there restrictions on the means of news production and distribution? (0-4 points)• Is there a monopoly on the means of production, such as newsprint supplies, allocations of paper,film, or Internet service providers?• Are there private and non-state printing presses?• Are channels of news and information distribution (kiosks, transmitters, cable operators, Internet,mobile phones) able to operate freely?• Does the government exert pressure on independent media through the control of distributionfacilities?• Is there seizure or destruction of copies of newspapers, film, or production equipment?• Does geography or poor infrastructure (roads, electricity etc) limit dissemination of print,broadcast, or internet-based news sources throughout the country?5. Are there high costs associated with the establishment and operation of media outlets?(0-4 points)• Are there excessive fees associated with obtaining a radio frequency, registering a newspaper, orestablishing an ISP?• Are the costs of purchasing paper, newsprint, or broadcasting equipment subject to highadditional duties?• Are media outlets subject to excessive taxation or other levies compared to other industries?• Are there restrictions on foreign investment or non-investment foreign support/funding in themedia?6. Do the state or other actors try to control the media through allocation of advertising orsubsidies? (0-3 points)• Are subsidies for privately run newspapers or broadcasters allocated fairly?• Is government advertising allocated fairly and in an apolitical manner?• Is there use of withdrawal of advertising (i.e. government stops buying ad space in some papersor pressures private firms to boycott media outlets) as a way of influencing editorial decisions?7. Do journalists, bloggers, or media outlets receive payment from private or publicsources whose design is to influence their journalistic content? (0-3 points)• Do government officials or other actors pay journalists in order to cover or to avoid certainstories?• Are journalists often bribed?24

• Are pay levels for journalists and other media professionals sufficiently high to discouragebribery?• Do journalists or media outlets request bribes or other incentives in order to cover or hold certainstories?8. Does the overall economic situation negatively impact media outlets’ financialsustainability? (0-4 points)• Are media overly dependent on the state, political parties, big business, or other influentialpolitical actors for funding?• Is the economy so depressed or so dominated by the state that a private entrepreneur would find itdifficult to create a financially sustainable publication or broadcast outlet?• Is it possible for independent publications or broadcast outlets to remain financially viableprimarily by generating revenue from advertising or subscriptions?• Do foreign investors or donors play a large role in helping to sustain media outlets?• Are private owners subject to intense commercial pressures and competition, thus causing them totailor or cut news coverage in order for them to compete in the market or remain financiallyviable?25