Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

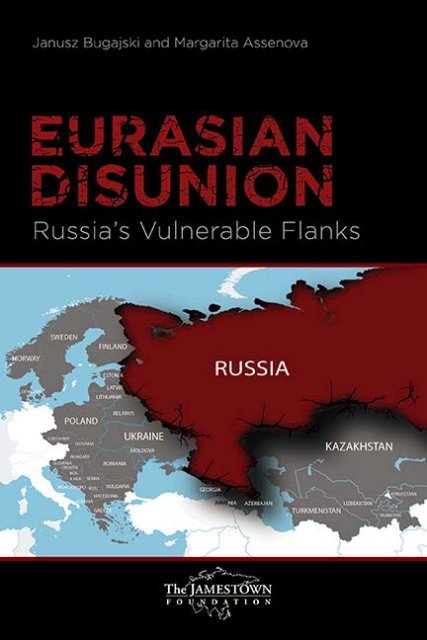

<strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

Russia’s Vulnerable Flanks<br />

__________________________________________________<br />

By Janusz Bugajski and Margarita Assenova<br />

Washington, DC<br />

June 2016

THE JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION<br />

Published in the United States by<br />

The Jamestown Foundation<br />

1310 L Street NW<br />

Suite 810<br />

Washington, DC 20005<br />

http://www.jamestown.org<br />

Copyright © 2016 The Jamestown Foundation<br />

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this<br />

book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written consent.<br />

For copyright and permissions information, contact The Jamestown<br />

Foundation, 1310 L Street NW, Suite 810, Washington, DC 20005.<br />

The views expressed in the book are those of the authors and not necessarily<br />

those of The Jamestown Foundation.<br />

For more information on this book of The Jamestown Foundation, email<br />

pubs@jamestown.org.<br />

ISBN: 978-0-9855045-5-7<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Names: Bugajski, Janusz, 1954- author. | Assenova, Margarita author.<br />

Title: Eurasian disunion : Russia's vulnerable flanks / Janusz Bugajski and<br />

Margarita Assenova.<br />

Description: Washington, DC : The Jamestown Foundation, 2016.<br />

Identifiers: LCCN 2015034025 | ISBN 9780985504557 (pbk.)<br />

Subjects: LCSH: Russia (Federation)--Foreign relations--21st century. |<br />

Russia (Federation)--Boundaries. | Geopolitics--Russia (Federation) |<br />

Geopolitics--Eurasia.<br />

Classification: LCC JZ1616 .B839 2015 | DDC 327.47--dc23<br />

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015034025<br />

Cover art provided by Peggy Archambault of Peggy Archambault Design.

i<br />

Jamestown’s Mission<br />

The Jamestown Foundation’s mission is to inform and educate policy<br />

makers and the broader community about events and trends in those<br />

societies which are strategically or tactically important to the United<br />

States and which frequently restrict access to such information.<br />

Utilizing indigenous and primary sources, Jamestown’s material is<br />

delivered without political bias, filter or agenda. It is often the only<br />

source of information which should be, but is not always, available<br />

through official or intelligence channels, especially in regard to<br />

Eurasia and terrorism.<br />

Origins<br />

Founded in 1984 by William Geimer, The Jamestown Foundation<br />

made a direct contribution to the downfall of Communism through<br />

its dissemination of information about the closed totalitarian societies<br />

of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.<br />

William Geimer worked with Arkady Shevchenko, the highestranking<br />

Soviet official ever to defect when he left his position as<br />

undersecretary general of the United Nations. Shevchenko’s memoir<br />

Breaking With Moscow revealed the details of Soviet superpower<br />

diplomacy, arms control strategy and tactics in the Third World, at<br />

the height of the Cold War. Through its work with Shevchenko,<br />

Jamestown rapidly became the leading source of information about<br />

the inner workings of the captive nations of the former Communist<br />

Bloc. In addition to Shevchenko, Jamestown assisted the former top<br />

Romanian intelligence officer Ion Pacepa in writing his memoirs.<br />

Jamestown ensured that both men published their insights and<br />

experience in what became bestselling books. Even today, several<br />

decades later, some credit Pacepa’s revelations about Ceausescu’s<br />

regime in his bestselling book Red Horizons with the fall of that<br />

government and the freeing of Romania.

ii<br />

The Jamestown Foundation has emerged as a leading provider of<br />

information about Eurasia. Our research and analysis on conflict and<br />

instability in Eurasia enabled Jamestown to become one of the most<br />

reliable sources of information on the post-Soviet space, the Caucasus<br />

and Central Asia as well as China. Furthermore, since 9/11,<br />

Jamestown has utilized its network of indigenous experts in more than<br />

50 different countries to conduct research and analysis on terrorism<br />

and the growth of al-Qaeda and al-Qaeda offshoots throughout the<br />

globe.<br />

By drawing on our ever-growing global network of experts,<br />

Jamestown has become a vital source of unfiltered, open-source<br />

information about major conflict zones around the world—from the<br />

Black Sea to Siberia, from the Persian Gulf to Latin America and the<br />

Pacific. Our core of intellectual talent includes former high-ranking<br />

government officials and military officers, political scientists,<br />

journalists, scholars and economists. Their insight contributes<br />

significantly to policymakers engaged in addressing today’s newly<br />

emerging global threats in the post 9/11 world.

iii<br />

Table of Contents<br />

Jamestown’s Mission…………………………………………...i<br />

Acknowledgements…………………………………………....iv<br />

Foreword………………………………………………………..v<br />

Executive Summary……………………………………………1<br />

1. Introduction: Russia’s Imperial Agenda…………………...3<br />

2. Northern Flank: Baltic and Nordic………………………..66<br />

3. Western Flank: East Central Europe…………………….139<br />

4. South Western Flank: South East Europe……………….219<br />

5. Southern Flank: South Caucasus………………………....282<br />

6. South Eastern Flank: Central Asia……………………….370<br />

7. Conclusion: Russia’s Future and Western Responses…..461<br />

Appendix I: Maps of Vulnerable Flanks……………………499<br />

Appendix II: Author Biographies…………………………..504

iv<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We would like to extend our utmost thanks to all the people we<br />

consulted and debated in Washington and along each of Russia’s<br />

vulnerable flanks in the Wider Europe and Central Asia. Our sincere<br />

gratitude to The Jamestown Foundation and its President Glen<br />

Howard for being at the forefront of prescient analysis on Russia and<br />

the “Eurasian” world. Finally, exceptional praise for Matthew Czekaj,<br />

Program Associate for Europe and Eurasia at The Jamestown<br />

Foundation, for his outstanding and rapid reaction editing.

v<br />

Foreword<br />

This monumental work dissects the international ambitions of the<br />

Russian government under the presidency of Vladimir Putin. Since he<br />

gained power over fifteen years ago, the former KGB colonel has<br />

focused his attention on rebuilding a Moscow-centered bloc in order<br />

to return Russia to global superpower status and to compete<br />

geopolitically with the West. As a result of the Kremlin’s expansionist<br />

objectives, the security of several regions that border the Russian<br />

Federation has been undermined and, in some cases, the national<br />

independence and territorial integrity of nearby states has been<br />

violated.<br />

Janusz Bugajski and Margarita Assenova’s thoroughly researched<br />

volume not only assesses Moscow’s ambitions, strategies and tactics,<br />

it also meticulously details the various tools used by the Kremlin to<br />

integrate or subvert its neighbors and to weaken NATO and the<br />

European Union. It examines five major flanks along Russia’s borders<br />

that are particularly prone to Moscow’s aggressiveness—from the<br />

Arctic and the Baltic to the Caspian and Central Asia—and analyzes<br />

the various instruments of pressure that Moscow employs against<br />

individual states.<br />

No other work of this depth and breadth has been produced to date.<br />

At a time when Russia’s revisionism and expansionism is accelerating,<br />

it is essential reading for policymakers and students of competitive<br />

geopolitics. In addition to examining Russia’s assertive policies, the<br />

authors assess the future role of NATO, the EU, and the US in the<br />

Wider Europe and offer several concrete policy recommendations for<br />

Washington and Brussels that would consolidate a more effective<br />

trans-Atlantic alliance to ensure the security of states bordering a

vi<br />

volatile Russia.<br />

Glen Howard<br />

President, Jamestown Foundation<br />

May 2016

Executive Summary<br />

Russia’s attack on Ukraine and the dismemberment of its territory is<br />

not an isolated operation. It constitutes one component of a broader<br />

strategic agenda to rebuild a Moscow-centered bloc designed to<br />

compete with the West. The acceleration of President Vladimir<br />

Putin’s neo-imperial project has challenged the security of several<br />

regions that border the Russian Federation, focused attention on the<br />

geopolitical aspects of the Kremlin’s ambitions, and sharpened the<br />

debate on the future role of NATO, the EU, and the US in the Wider<br />

Europe.<br />

This book is intended to generate a more informed policy debate on<br />

the dangers stemming from the restoration of a Russian-centered<br />

“pole of power” or “sphere of influence” in Eurasia. It focuses on five<br />

vulnerable flanks bordering the Russian Federation—the Baltic and<br />

Nordic zones, East Central Europe, South East Europe, South<br />

Caucasus, and Central Asia. It examines several pivotal questions<br />

including: the strategic objectives of Moscow’s expansionist<br />

ambitions; Kremlin tactics and capabilities; the impact of Russia’s<br />

assertiveness on the national security of its neighbors; the responses<br />

of vulnerable states to Russia’s geopolitical ambitions; the impact of<br />

prolonged regional turmoil on the stability of the Russian Federation<br />

and the survival of the Putinist regime; and the repercussions of<br />

heightened regional tensions for US, NATO, and EU policy toward<br />

Russia and toward unstable regions bordering the Russian Federation.

2 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

The book concludes with concrete policy recommendations for<br />

Washington and Brussels in the wake of the escalating confrontation<br />

with Russia. The Western approach toward Moscow needs to focus<br />

on consolidating a dynamic trans-Atlantic alliance, repelling and<br />

deterring a belligerent Russia, ensuring the security of all states<br />

bordering Russia, and preparing for a potential implosion of the<br />

Russian Federation.

1. Introduction: Russia’s Imperial<br />

Agenda<br />

Russia’s attack on Ukraine in February 2014 and the subsequent<br />

dismemberment of its territory is not an isolated operation. It<br />

constitutes one component of a much broader strategic agenda to<br />

rebuild a Moscow-centered bloc that is intended to compete with the<br />

West. The acceleration of Vladimir Putin’s neo-imperial project,<br />

prepared and implemented after he assumed the office of President in<br />

December 1999, has challenged the security of several regions that<br />

border the Russian Federation, refocused attention on the ideological<br />

and geopolitical aspects of the Kremlin’s ambitions, and sharpened<br />

the debate on the future role of NATO, the European Union, and the<br />

United States in the Wider Europe.<br />

To enable more effective Western responses to the growing threats<br />

from Moscow, urgently needed is a comprehensive assessment of the<br />

dangers stemming from the attempted restoration of a Russiancentered<br />

“pole of power” or “sphere of influence” in a loosely-defined<br />

“Eurasia.” This book is intended to generate a more informed policy<br />

debate by focusing on five regional flanks bordering the Russian<br />

Federation that remain vulnerable to Moscow’s subversion—the<br />

Baltic and Nordic zones (northern flank), East Central Europe<br />

(western flank), South East Europe (southwestern flank), South<br />

Caucasus (southern flank), and Central Asia (southeastern flank).

4 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

The book chronicles the diverse tools applied by the Kremlin against<br />

targeted neighbors and examines several pivotal questions: the<br />

strategic objectives of Moscow’s expansionist ambitions; the<br />

Kremlin’s tactics and capabilities; the impact of Russia’s assertiveness<br />

on the national security of its neighbors; the responses of vulnerable<br />

states to Russia’s geopolitical ambitions; the impact of prolonged<br />

regional turmoil on the stability of the Russian Federation and the<br />

survival of the Putinist regime; and the repercussions of heightened<br />

regional tensions for US, NATO, and EU policy toward Russia and<br />

toward unstable regions bordering the Russian Federation.<br />

Moscow’s Ambitions<br />

Following Putin’s installment as Russia’s President on December 31,<br />

1999, legitimized in presidential elections in March 2000, the Kremlin<br />

has been controlled by a narrow group of senior military, defense<br />

industry, and security service leaders, together with loyal state<br />

bureaucrats and tycoons or oligarchs owning or managing key<br />

national industries. This ruling elite is presided over by the primary<br />

decision-maker, former KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy<br />

Bezopasnosti, Committee for State Security) Colonel Vladimir Putin.<br />

The balance of power between different political factions has been a<br />

wellspring of speculation for Kremlinologists. Nonetheless, regardless<br />

of potential factionalism and diverse sectoral interests, Russia’s<br />

foreign policy objectives have proved relatively consistent under<br />

Putin’s rule. The narrow elite has exhibited no substantive dissenting<br />

voices, and key national decisions are reached within the presidential<br />

administration and not in the government cabinet. In this centralized<br />

and hierarchical context, it is valuable to consider the contours of<br />

Russia’s external policy goals.<br />

Some analysts have difficulties in explaining Putin’s motives. 1 Is<br />

staying in power the only ultimate goal, as a few observers have<br />

suggested, or is the prolonged maintenance of power necessary in

INTRODUCTION | 5<br />

order to achieve certain broader objectives? 2 The notion that the<br />

Kremlin’s domestic politics rather than its security calculations are at<br />

the root of Moscow’s foreign policy revanchism is too narrow and<br />

simplistic, as internal and external policies are closely intertwined.<br />

The maintenance of domestic power may be undergirded by personal<br />

ambitions, but it also incorporates broader dimensions to be effective,<br />

whether populist, messianic, nationalist, or imperialist. Putin appears<br />

to harbor a messiah complex, convinced that he serves a noble<br />

historical purpose to restore Russia’s glory and power. 3 For Putin and<br />

his entourage, Russia is an imperial enterprise.<br />

Putin spent the first few years of his presidency amassing personal<br />

control through the “power vertical” and by constructing a “managed<br />

democracy” beholden to the Kremlin. In this system, central and<br />

regional governments are selected by the Kremlin, parliament rubber<br />

stamps presidential decisions, presidential and parliamentary<br />

elections are defrauded, and the political opposition is harassed,<br />

marginalized, or outlawed. Putin’s presidential tenure has also been<br />

substantially extended. Under the amended constitution, Putin was<br />

elected for the third time on May 7, 2012, for six years and will be<br />

entitled to run again for President in 2018 for another six-year<br />

mandate.<br />

The notion that Putin’s only objective is to stay in power and amass a<br />

personal fortune regardless of the risk to Russia’s national interests<br />

fails to explain Moscow's assertive and confrontational foreign policy.<br />

It can be argued that deeper cooperation with the West would bring<br />

more extensive economic benefits and international legitimacy that<br />

would in turn strengthen Putin’s position inside Russia and expand<br />

his private assets. Engineering conflicts with neighbors and provoking<br />

disputes with Western governments can undermine the President’s<br />

position by damaging economic development and undermining<br />

Russia’s global standing even though, in the short term, the Kremlin<br />

is able to mobilize society against alleged external enemies to raise<br />

Putin’s popularity and support government policy.

6 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

The primary objective of Moscow’s foreign policy is to restore Russia<br />

as a major center or pole of power in a multipolar or multi-centric<br />

world. 4 Following the return of Putin to Russia’s presidency in May<br />

2012, after the Dmitry Medvedev interlude (2008–2012), the Kremlin<br />

reinvigorated its global ambitions and regional assertiveness. It also<br />

made more explicit the overarching goal to reverse the predominance<br />

of the United States within Europe and Eurasia. Kremlin officials<br />

believe that the world should be organized around a new global<br />

version of the 19 th century “Concert of Europe,” in which a handful of<br />

great powers balance their interests and smaller countries orbit<br />

around them. This constitutes multipolarity rather than<br />

multilateralism. In practice, such an approach would entail restoring<br />

the Yalta-Potsdam post–World War Two divisions, in which Moscow<br />

dominates Eurasia and half of Europe, but with a substantially<br />

diminished US presence in Europe. This would provide Russia with<br />

strategic depth in its active opposition to the West, including its<br />

professed values and security structures.<br />

Western observers frequently repeat the observation that Putin is a<br />

tactician and not a strategist, but invariably fail to distinguish between<br />

the two. In essence, tactics are short-term methods while strategies are<br />

longer-term policies, and both are intended to achieve specific<br />

objectives. While its goals are imperial, Kremlin strategies and tactics<br />

are flexible and “pragmatic” and this can make them more effective<br />

than a rigid approach. They include enticements, threats, incentives,<br />

pressures, and a variety of subversive actions where Russia’s national<br />

interests are deemed to predominate over those of its neighbors. By<br />

claiming that it is pursuing “pragmatic” national interests, the<br />

Kremlin engages in a combination of offensives by interjecting itself<br />

in neighbors’ affairs, capturing important sectors of local economies,<br />

subverting vulnerable political systems, corrupting national leaders,<br />

penetrating key security institutions, undermining national and<br />

territorial unity, conducting propaganda offensives through a<br />

spectrum of media and social outlets, and deploying a host of other<br />

tools to weaken obstinate governments that resist Moscow.

INTRODUCTION | 7<br />

Putin is often depicted in the West as an “opportunist” and not a<br />

strategist. However, opportunism is simply a means of benefiting<br />

from favorable circumstances and not an objective in itself. The<br />

question is what are Putin's objectives in creating or benefiting from<br />

opportunities to assert Russian power? Several analysts believe that<br />

the President may not have a coherent plan or goal to extend or revive<br />

the Russian empire, but may be simply acting out of spite to<br />

undermine security in neighboring countries and to obstruct Western<br />

enlargement. 5 Other analysts not only challenge the existence of any<br />

plans for imperial restoration, but also claim that the Kremlin simply<br />

acts defensively to protect its interests in neighboring states from an<br />

expanding and threatening West. 6<br />

There is some confusion in such assessments between Russia’s<br />

ambitions and capabilities. While Moscow’s goals remain fairly clear,<br />

as the government has consistently stated and acted to consolidate a<br />

predominant sphere of influence in territories designated as the “post-<br />

Soviet space,” the regional extent of this Russian sphere, the response<br />

of each targeted country, and the ability to accomplish such a task<br />

without provoking substantial international resistance are much less<br />

predictable. Hence, the methods employed by the Kremlin require<br />

substantial flexibility, eclecticism, opportunism, and improvisation.<br />

Since Russia’s attack on Ukraine in early 2014, the term “hybrid war”<br />

has been widely employed to describe Moscow’s subversion of a<br />

targeted neighbor. 7 While the concept generally signifies that the<br />

Kremlin deploys a mix of instruments against its adversaries, it fails to<br />

pinpoint the tactics, objectives, capabilities, and results of Moscow’s<br />

offensive. It also assumes that the Kremlin has invented a novel form<br />

of warfare rather than pursuing a modern adaptation of traditional<br />

attempts to subvert the psychology, economy, polity, society, and<br />

military of specific states without necessarily engaging in a direct<br />

military offensive.

8 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

Russia’s neo-imperial geopolitical project no longer relies on Sovietera<br />

mechanisms vis-à-vis bordering states, such as strict ideological<br />

allegiance, the penetration and control of local ruling parties and<br />

security services, periodic military force, the permanent stationing of<br />

Russian troops, and almost complete enmeshment with the Russian<br />

economy. Instead, sufficient tools of pressure are applied to try and<br />

ensure the primary goal—for Moscow to exert predominant influence<br />

over the foreign and security policies of immediate neighbors so that<br />

they will either remain neutral or support Russia’s international<br />

agenda and not challenge the legitimacy of the Putinist system. The<br />

ultimate goal is to establish protectorates around the country’s<br />

borders, which do not forge close and independent ties with each<br />

other and do not enter Western institutions.<br />

In this expansionist international context, it is useful to distinguish<br />

between Russia’s national interests and its state ambitions. Moscow’s<br />

security is not challenged by the accession to NATO of neighboring<br />

states. However, its ability to control the security dimensions and<br />

foreign policy orientations of these countries is challenged by their<br />

incorporation in the Alliance because NATO provides security<br />

guarantees against Russia's potential aggression.<br />

While pursuing a neo-imperial agenda, Moscow has also calculated<br />

that if it cannot control the security policies of its neighbors, it is<br />

preferable to have uncertainty and insecurity along its borders. This<br />

enables the Kremlin to frighten its own public with perceptions of<br />

threat to Russia's stability and to undermine the NATO and EU<br />

accession prospects of several neighbors. An assertive foreign policy<br />

helps to distract attention from convulsions inside the Russian<br />

Federation. Putin’s policy is presented as vital to national security by<br />

protecting Russia from internal turmoil, avowedly sponsored by<br />

Washington, in which NATO and EU enlargement is portrayed as<br />

evidence of aggressive “Russophobia.”

INTRODUCTION | 9<br />

In its eclectic ideological packaging, Putinism consists of a blend of<br />

Russian statism, great power chauvinism, pan-Slavism, pan-<br />

Orthodoxy, multi-ethnic Eurasianism, Russian nationalism (with<br />

increasing ethno-historical ingredients), social conservatism, antiliberalism,<br />

anti-Americanism, and anti-Westernism. At the heart of<br />

this heady brew is the notion of restoring Russia’s glory and global<br />

status that was allegedly subdued and denied after the collapse of the<br />

Soviet Union through a combination of Western subversion and<br />

domestic treason.<br />

In reviving the image of greatness, Russia continues to live in the<br />

categories of World War Two. The officially promoted historical<br />

narrative of the “Great Patriotic War” has been employed as a source<br />

of national unity and loyalty to the state. The war is a key element in<br />

Moscow’s self-glorifying propaganda. Russia is presented as a global<br />

power with a stellar history, while Stalinism is depicted as a necessary<br />

system that modernized the state and defeated Nazi Germany. This<br />

imparts the message that the current authoritarian regime can also<br />

violate human rights and capsize living standards, as long as it is<br />

determined to restore the glory of the “Russian World” (Russkiy Mir).<br />

World War Two myths in Russia present two stark stereotypes: people<br />

who support the Kremlin are patriots and antifascists, while those who<br />

oppose are labeled as fascists regardless of actual political<br />

persuasions. 8<br />

The Putin administration believes that it can violate human rights and<br />

the integrity of neighboring states in the service of restoring Russia’s<br />

glory. The “ideology of identity” has grown into a vital component of<br />

national populism, expressed in the concept of the “Russian World.”<br />

This collectivist formula is both cultural and genetic and supposedly<br />

includes all Russian ethnics, Russian speakers, and descendants of<br />

both categories in any country. The term is underpinned by statist<br />

messianism, whereby the Russian government is obliged by history<br />

and divine fate to protect this broad community and defend it in<br />

particular against Western influences. Various elements of Soviet

10 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

chekism (or the cult of state security) have also been revived and<br />

presented as a rebirth of national pride: “Growing reverence for the<br />

security apparatus reflects a broader trend toward reverence for<br />

strong statehood in Russia.” 9 Putin is heralded as a chekist patriot who<br />

is restoring Russia’s internal order and international stature.<br />

Russia’s Capabilities<br />

As a resurgent neo-imperialist power that seeks to prove its<br />

robustness, Russia cannot display weakness toward the West. Hence,<br />

the country’s economic limitations and escalating internal problems<br />

are disguised by state propaganda, while the recreation of a Eurasian<br />

bloc is supposed to demonstrate that Russia is a rising power and not<br />

a declining empire. Although Putin’s ambition to create a new<br />

Moscow-centered Eurasian Union is unlikely to be successful, given<br />

Russia’s ongoing economic decline and the resistance of most<br />

neighboring states, attempts to create such a bloc could destabilize a<br />

broad region along Russia’s long flanks, particularly throughout<br />

Europe’s East and in Central Asia.<br />

As the largest Kremlin target, Ukraine serves as a valuable example of<br />

the impact of Moscow’s imperial ambitions. After Putin returned to<br />

Russia’s Presidency in May 2012, the Kremlin began to intensify its<br />

pressures on the former Soviet republics to participate in its<br />

integrationist projects. Moscow became fearful that the post-Soviet<br />

territories could drift permanently into either the Western or Chinese<br />

"spheres of influence." Putin’s Eurasian alliance is thereby designed to<br />

balance the EU and NATO in the west and China in the east.<br />

Economic linkages are intended to reinforce political and security<br />

connections, making it less likely that Russia’s neighbors can join<br />

alternative blocs.<br />

To achieve its ambitions, Moscow needs to assemble around itself a<br />

cluster of states that are loyal or subservient to Russian foreign policy

INTRODUCTION | 11<br />

and security interests. Unlike the EU—where states voluntarily pool<br />

their sovereignty, decisions are taken by consensus, and no single state<br />

dominates decision-making—in Moscow’s integrative institutions,<br />

countries are expected to permanently surrender elements of their<br />

sovereignty to the center. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the<br />

major multi-national organizations promoted by the Kremlin to<br />

enhance Eurasian integration have included the Commonwealth of<br />

Independent States (CIS), the Collective Security Treaty Organization<br />

(CSTO), the Eurasian Economic Community (EEC), the Customs<br />

Union (CU), and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). The EEU was<br />

formally established in January 2015 as the optimal multi-national<br />

format. 10<br />

The transition to the EEU has been described as the final goal of<br />

economic integration and is to include a free trade regime, unified<br />

customs and nontariff regulation measures, common access to<br />

internal markets, a unified transportation system, a common energy<br />

market, and a single currency. These integrative economic measures<br />

are to be undergirded by a tighter political and security alliance both<br />

through the CSTO and in bilateral arrangements with Russia. 11<br />

Putin was encouraged in his neo-imperial restorationist endeavors by<br />

favorable international conditions, most evident in the approach of<br />

President Barack Obama’s administration. As a by-product of the<br />

White House accommodating “reset” policy toward Moscow,<br />

launched in early 2009, Washington curtailed its campaign to enlarge<br />

NATO and secure the post-Soviet neighborhood within Western<br />

structures. This increased the vulnerability of several states to<br />

Moscow’s pressures and enticements and convinced Putin that his<br />

freedom of maneuver in the post-Soviet sphere was expanding.<br />

Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the Central<br />

Asian states were not priority interests for the White House, and some<br />

US policy makers appeared to approve of a Russian political and<br />

economic umbrella over these countries.

12 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

The net impact of the Obama approach was to convince Moscow that<br />

the US was withdrawing from international commitments after the<br />

Iraq and Afghanistan wars and had neither the resources, political<br />

will, nor public support to challenge Russia’s re-imperialization.<br />

Moscow also concluded that despite the EU’s Eastern Partnership<br />

outreach program, the European Union would remain divided and<br />

preoccupied with its internal problems and would not challenge<br />

Russia’s economic hegemony among its immediate neighbors.<br />

Moscow’s assumptions have been partly vindicated by the ease of its<br />

division of Ukraine, through the capture of Crimea, and the limited<br />

economic sanctions imposed by Western capitals. Nonetheless,<br />

Russia’s assault on Ukraine has also unleashed protective measures in<br />

several neighboring states and revived calls for strengthening NATO’s<br />

presence throughout Europe’s East.<br />

In the aftermath of the crisis over Ukraine, Moscow has reanimated<br />

the Western geopolitical scapegoat. It justifies its attack on Ukraine as<br />

a necessary offensive to counter Western subversion and<br />

destabilization. Russia’s leaders depict the West as dangerous and<br />

unpredictable, and accuse the US of using “irregular warfare” such as<br />

NGOs and multinational institutions, including the International<br />

Monetary Fund (IMF), to conduct “color revolutions” and destabilize<br />

Russia. 12 Hence, any attempt at democratization along its borders<br />

makes Russia more vulnerable to Western machinations. Russia is<br />

also allegedly the victim of NATO expansion, whereby the<br />

incorporation of East Central Europe (ECE) in the North Atlantic<br />

Alliance was primarily intended to undermine Moscow. The next<br />

stage purportedly planned by Washington is to foster conflicts within<br />

the Russian Federation by using civil society, mass media, and human<br />

rights groups and by supporting Islamic insurgencies. Westernization<br />

is deemed a subversive weapon embodying many elements of<br />

Russophobia.<br />

Putin has declared that Russia is under a growing multitude of outside<br />

threats emanating from the US and its allies. In particular, the West

INTRODUCTION | 13<br />

purportedly organized and provoked the Ukrainian crisis in 2014 in<br />

order to have an excuse to reinvigorate NATO and deploy Western<br />

forces closer to Russia’s borders. Moscow will respond by deploying<br />

new offensive nuclear weapons aimed at Western nations, by<br />

updating its air and missile defense system, and by producing new<br />

precision-guided weapons. 13 Moscow is also determined to violate any<br />

treaty that obstructs its imperial agenda, including the December 1994<br />

Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances intended to<br />

guarantee the inviolability of Ukraine’s borders.<br />

Russia's new military doctrine signed by Putin in December 2014<br />

describes an increasingly threatening international environment that<br />

can generate problems at home. 14 It claims intensifying “global<br />

competition” and direct threats emanating from NATO and the US in<br />

particular. The document contends that among the most serious<br />

regional hazards are conspiracies to “overturn legitimate<br />

government” in neighboring states and establish regimes that threaten<br />

Russia's interests. Such alleged American ploys are linked with the<br />

placement of Western forces in countries adjoining Russia and<br />

NATO’s development of anti-ballistic missile (ABM), space-based,<br />

and rapid reaction forces. The new military doctrine also calls for<br />

Moscow to counter the use of communications technologies against<br />

Russia, such as cyber-warfare and social networks.<br />

Moscow asserts that it will counter Western attempts to gain strategic<br />

superiority by deploying strategic missile defense systems. 15 It also<br />

reserve the right to use nuclear weapons in response to the use of<br />

nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction against Russia or its<br />

allies, and even in case of “aggression” against Russia with<br />

conventional weapons that would endanger the existence of the state.<br />

The underlying geopolitical objective of the Eurasian Economic<br />

Union (EEU) is to create an alternative power center to EU<br />

integration.<br />

16<br />

However, the politically motivated EEU is a<br />

protectionist arrangement that will cost Russia substantial amounts of

14 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

resources, harm its economy, and further alienate the country<br />

internationally. It may also retard the economic development of other<br />

integrated states. By contrast, the “deep and comprehensive free trade<br />

agreements” (DCFTA) offered by the EU to many post-Soviet states<br />

is based on the removal of tariff barriers and the adoption of a large<br />

part of EU regulations. The stimulus offered by the EU for integration<br />

into its internal market restricts Russia’s opportunities to maintain<br />

political control over these states. It also promotes commitments to<br />

EU principles of legalism and governance and the application of<br />

regulatory standards in exchange for access to a market with a<br />

population of 500 million and with rapid growth potential. 17<br />

By contrast, EEU membership could mean lower energy prices, freer<br />

trade in the Eurasian space with a population of 170 million but with<br />

significantly lower purchasing power than in the EU, as well as slow<br />

economic restructuring and the strengthening of oligarchic and<br />

authoritarian management. In exchange for low energy prices and<br />

access to its domestic market, Russia intends to take over strategic<br />

sectors of the EEU economies and strengthen its influence within<br />

member states. This would guarantee that each state remains tethered<br />

to Russia regardless of leadership changes and the temptations of<br />

Western integration.<br />

Through enhanced free trade agreements, the EU does not prevent<br />

further integration of the post-Soviet countries with each other, but<br />

once they become parties to Russia’s Customs Union and the EEU,<br />

they are deprived of the opportunity to have bilateral agreements with<br />

the EU. Hence, each European capital needs to make a choice, as<br />

participation in customs agreements involving countries that have not<br />

harmonized their legislative framework with EU requirements<br />

precludes free trade with the EU. In sum, the EEU is incompatible<br />

with the core principles of the EU’s external policy: it remains a<br />

project for trade simplification between non-liberal regimes.

INTRODUCTION | 15<br />

Russia’s escalating economic difficulties following the drastic fall in<br />

crude oil prices in 2014–2015 and the gradual impact of Western<br />

financial sanctions led to a ruble crisis and heightened the risk of<br />

maintaining close economic ties with Russia. All three of Moscow’s<br />

EEU partners (Armenia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan) have been<br />

negatively affected by the collapse in value of Russia’s currency. 18 For<br />

instance, the decline in the Russian market because of Western<br />

sanctions and the collapse of oil prices has cost the Belarusian<br />

economy almost $3 billion. 19 Moreover, the EEU is rife with internal<br />

divisions that will render it ineffective and unattractive to the broader<br />

region. In a sign of growing friction, after Moscow imposed retaliatory<br />

sanctions on EU agricultural produce in the summer of 2014, Belarus<br />

benefitted by re-exporting EU goods to Russia. The Kremlin reacted<br />

in November 2014 by banning the import of meat and dairy products<br />

from Belarus. In sum, divisions between an economically unstable<br />

Russia and its anxious neighbors will result in an ineffective and weak<br />

EEU.<br />

The most grievous repercussions of Moscow’s empire building have<br />

been witnessed in Ukraine, which remains the key prize in Kremlin<br />

plans to recombine the former Soviet republics. With control over<br />

Ukraine, Moscow could project its influence into Central Europe;<br />

without Ukraine, the planned Eurasian bloc would become a largely<br />

north Asian construct or a patchwork of states most susceptible to<br />

Moscow’s pressures.<br />

The anti-Ukrainian war launched in February 2014 was coordinated<br />

from the Kremlin, as only the President’s office possesses the levers of<br />

control necessary to conduct such an operation. The Kremlin’s main<br />

fear in Ukraine was not the avowedly endangered status of the<br />

Russian-speaking population. Its public paranoia was rooted in the<br />

prospect of Ukraine developing into a democratic, unified, and<br />

increasingly prosperous state that moves toward EU accession and<br />

eventual NATO membership. Such a model of development could<br />

become increasingly attractive for Russia’s other neighbors and even

16 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

for some of Russia’s diverse regions. This would challenge the<br />

legitimacy and longevity of the kleptocratic and authoritarian Putinist<br />

system. For the Putinists, an independent and democratic Ukraine<br />

symbolizes everything that threatens their hold on power and disrupts<br />

plans to restore a Greater Russia. At the core of this deep hostility is<br />

the convenient conviction that Kyiv experienced a coup d'état<br />

camouflaged as a “color revolution” engineered by the West and<br />

ultimately designed to destroy Russia.<br />

The various “color revolutions,” whether Rose in Georgia (2003) or<br />

Orange in Ukraine (2004), are viewed in the West as indigenous<br />

attempts to prevent authoritarian backsliding, electoral manipulation,<br />

and popular disenfranchisement in the post-Soviet world. US and<br />

Western European organizations may have played supportive roles in<br />

these popular rebellions, but it was local activists who mobilized the<br />

public against the abusive elites. The ultimate outcome of such<br />

rebellions may be corroded or even reversed over time, but they<br />

provide hope that broader sectors of society can have a voice in the<br />

political process.<br />

For Russian officials and pro-Kremlin analysts, “color revolutions”<br />

are negative phenomenon imposed from outside with unpredictable<br />

consequences. And if the results threaten to culminate in democratic<br />

reforms and Western integration, then the revolutions must be<br />

countered. Hence, the covert attack and partition of Ukraine are<br />

intended to prove that Ukraine is a failing state. Furthermore, in all<br />

post-Soviet countries, regardless of their political structures, the<br />

Kremlin seeks to limit national sovereignty by deciding on their<br />

foreign policy and security orientations.<br />

In justifying foreign intervention, Aleksandr Bortnikov, head of the<br />

KGB successor, the Federal Security Service (Federalnaya Sluzhba<br />

Bezopasnosti, FSB), stated that his agency would react quickly and<br />

harshly to any attempt to overthrow existing regimes in the post-<br />

Soviet countries. 20 This indicates a pervasive fear in the Kremlin that

INTRODUCTION | 17<br />

the Ukrainian revolution against a government devoid of public trust<br />

could be replicated in Russia itself. Bortnikov claimed that<br />

“destructive forces” were financed by Western NGOs, thereby giving<br />

Russia’s security services a license to target social activists, private<br />

institutions, and the liberal political opposition at home and to<br />

combat Western-inspired revolutions among its neighbors.<br />

Arsenal of Subversion<br />

Moscow employs diverse tools and methods to undermine its<br />

adversaries and to control its allies. It pursues various forms of<br />

subversion against specific states, with the exact recipe of policies<br />

dependent on the vulnerabilities and responses of targeted capitals.<br />

The Kremlin arsenal consists of a mixture of threats, pressures,<br />

enticements, rewards, and punishments, and it can be grouped into<br />

eight main clusters: international, informational, ideological,<br />

economic, ethnic, political, social, and military.<br />

International<br />

1. Diplomatic Pressures: High-level visits by Russian dignitaries or<br />

the deliberate snubbing of certain governments serve as standard<br />

diplomatic devices to extract concessions and voice approval or<br />

disapproval for specific foreign policies. Treaties and other interstate<br />

agreements are highlighted, ignored, or rejected to exert<br />

pressure on specific governments. Even when bilateral treaties<br />

recognizing existing borders are signed with neighbors, their<br />

ratification by the parliament is deliberately delayed or their<br />

validity is overlooked. Sometimes, grander historical justifications<br />

are offered that purportedly invalidate an existing accord, as<br />

witnessed in the forceful annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in<br />

2014.

18 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

The Russian parliament (Duma) also influences the political<br />

climate through combative statements and radical policy<br />

prescriptions by deputies that may make the government appear<br />

more moderate. This injects a sense of threat toward neighbors<br />

and raises regional anxieties. For instance, some Duma deputies<br />

have questioned the legality of the break-up of the USSR and the<br />

independence of the Baltic states and other former Soviet<br />

republics.<br />

2. Deceptive Diplomacy: This can include offers of peace talks,<br />

mediation efforts, and conflict resolution at a time when Moscow<br />

is pursuing state dismemberment and other forms of subversion<br />

against specific neighbors. Deception, disinformation, and denial<br />

of responsibility for aggression are customary hallmarks of<br />

Russian foreign policy. Deception operations to mislead foreign<br />

political and military leaders are coordinated and conducted<br />

through diplomatic channels and government agencies in which<br />

false information is leaked and actual policy measures are<br />

camouflaged. Moscow also favors secret and bilateral meetings<br />

with US and EU representatives that can decide on some pressing<br />

questions in order to split any unified position by its Western<br />

adversaries.<br />

3. Strategic Posturing: Instead of posing as a superior systemic and<br />

economic alternative to the West, as it did during the Soviet era,<br />

the Kremlin depicts Russia as an indispensable global partner.<br />

Supposedly, cooperation with Moscow is vital in resolving<br />

numerous international problems, including Iran’s and North<br />

Korea’s nuclear programs, the spread of jihadist terrorism, the<br />

proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), global<br />

climate change, economic security, and a number of regional<br />

disputes. To underscore Russia’s importance and gain advantages<br />

in other areas, officials engage in strategic blackmail by asserting<br />

that they can terminate their diplomatic assistance to Washington

INTRODUCTION | 19<br />

or Brussels if they are opposed in some other policy domain.<br />

Conversely, the positive outcome of US-Russia cooperation may<br />

be stressed in various arenas to remove the spotlight from<br />

Moscow’s attack on a neighbor, to discourage Western sanctions,<br />

and to encourage further collaboration. The overriding message is<br />

that Russia must be afforded a free hand in its post-Soviet<br />

neighborhood in return for its cooperation on matters of more<br />

vital concern to Washington and Brussels.<br />

4. International Self-Defense: Russian leaders portray the country as<br />

the bastion of international law and the defender of independent<br />

statehood around the globe. Russia’s “sovereign democracy” is<br />

displayed as a valid political model that can be emulated more<br />

widely, especially as protection against American imperialism.<br />

Washington is supposedly intent on severing economic ties<br />

between Russia and the EU in order to boost America’s<br />

competitive position. It is also encircling Russia with loyal<br />

regimes, building a missile defense system to disarm Russia, and<br />

taking other aggressive measures to prevent Moscow from<br />

restoring its rightful role as a global power. Such policies are<br />

allegedly mirrored toward other emerging powers, particularly<br />

China. In an act of self-defense to counterbalance US political and<br />

economic hegemony, Moscow has formed the Eurasian Economic<br />

Union (EEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization<br />

(CSTO) on the former Soviet territories and is an active member<br />

of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the BRICS<br />

(Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) initiative. It casts<br />

itself as the bastion of global protection against the aggressive<br />

West and a hegemonic America.<br />

5. Ambassadorial Interference: The appointment of high-ranking<br />

or Kremlin-connected Russian politicians as ambassadors to<br />

neighboring states engenders a more intensive involvement in<br />

domestic politics and resembles a quasi-colonial or protectorate<br />

relationship. In some cases, as in Serbia, Montenegro, and

20 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

Macedonia, Russian ambassadors have been publicly outspoken<br />

against NATO enlargement and pose as the defenders of<br />

incumbent governments against Western pressures and US<br />

interference. Conversely, some foreign diplomats stationed in<br />

Moscow and other Russian cities have been subject to verbal and<br />

physical harassment as well as media defamation with the evident<br />

approval of the authorities in Moscow.<br />

6. Espionage Enhancement: A substantial increase in Russian<br />

embassy staff has been recorded in every Central and East<br />

European capital since Putin’s assumption of power in 1999,<br />

indicating that espionage activities have greatly expanded through<br />

Russia’s missions abroad. Russia has hundreds of intelligence<br />

officers at work in Europe, recruiting thousands of agents. 21 They<br />

are sometimes based at embassies and other diplomatic missions<br />

under official cover, but in many cases work as business people,<br />

academics, or students to penetrate targeted societies. Russia’s<br />

three major espionage services have benefited from increasing<br />

funding during Putin’s term: the Foreign Intelligence Service<br />

(Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki, SVR); the Federal Security Service<br />

(Federalnaya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti, FSB), and the military<br />

intelligence service (Glavnoye Razvedyvatelnoye Upravleniye,<br />

GRU). SVR, FSB, and GRU operations against the West have<br />

expanded to levels reminiscent of the height of the Cold War.<br />

Many of the spies are younger and more educated than during the<br />

Soviet era and have an ideological commitment to restoring<br />

Russia’s global status.<br />

7. Spy Recruitment: Russia’s espionage networks help identify<br />

corruptible or otherwise vulnerable politicians, officials,<br />

businesspeople, journalists, academics, and other public figures in<br />

the West. They also seek to recruit border guards and law<br />

enforcement personnel as informers. Moscow has also<br />

accumulated substantial experience in conducting “false flag”

INTRODUCTION | 21<br />

operations, in which individuals are recruited under the guise of<br />

different causes, such as environmentalism, media freedom,<br />

minority rights, or campaigns against government surveillance in<br />

the West.<br />

8. Intelligence Penetration: Former intelligence and counterintelligence<br />

contacts in the former Communist states are utilized<br />

by Moscow, especially as some governments have possessed a<br />

limited new pool of agents and continue to employ professionals<br />

with ex-KGB connections. Western intelligence services remain<br />

concerned about Communist-era links and have demanded the<br />

protection of intelligence sources and a thorough screening of<br />

operatives, especially if a country aspires to NATO entry. Periodic<br />

revelations about the extent of Russia’s espionage also serve<br />

Kremlin objectives by discrediting the trustworthiness and<br />

competence of government agencies in states canvassing for<br />

NATO accession or already Alliance members but supposedly<br />

penetrated by hostile foreign services.<br />

9. Creating Legal Chaos: Russia is creating legal chaos in a number<br />

of neighboring countries where it has intervened to establish or<br />

occupy separate territorial units or to annex them. “Frozen<br />

conflicts” are de facto territories where these is legal confusion for<br />

local residents. By annexing Crimea, supporting separatism in<br />

Abkhazia and South Ossetia, backing secessionism in<br />

Transnistria, and propping up independence claims in the<br />

Donbas region of Ukraine, Russia creates legal pandemonium<br />

that may never be resolved.<br />

The main legal problems resulting from these actions concern<br />

citizenship. In Crimea, a large share of the population retains<br />

Ukrainian citizenship and opposes Russia’s annexation of the<br />

peninsula. In the Russian-occupied Georgian provinces of<br />

Abkhazia and South Ossetia, thousands of Georgians refuse to<br />

denounce their citizenship and face harassment and frequent

22 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

detention by the self-proclaimed authorities. 22 In Moldova, the<br />

majority of Transnistria’s residents hold Russian, Ukrainian, or<br />

some other passports besides Moldovan, as the Transnistrian<br />

document is not recognized internationally and is not valid for<br />

travel. However, in 2014, thousands of Transnistrian residents<br />

applied to obtain Moldovan passports to take advantage of<br />

Moldova’s newly granted visa-free regime with the EU, despite<br />

Tiraspol’s request to the Russian Duma to draft a law that would<br />

allow their territory to join Russia. 23 By the end of 2014, half of<br />

Transnistria’s residents had confirmed their Moldovan<br />

citizenship. 24<br />

Moscow is finding it particularly difficult to bring Crimea into the<br />

common Russian legal space, because of differences in Ukrainian<br />

and Russian laws, penal codes, property deeds registration,<br />

benefits distribution, as well as the existing shortage of judiciary<br />

staff in the peninsula. According to Russian legal experts, even if a<br />

complete adaptation to Russian laws is concluded within two to<br />

three years, implementation will take much longer and the process<br />

will have an impact on Russia’s own legal system. 25<br />

10. Criminal Exploitation: Russia’s extensive international criminal<br />

networks are both a destabilizing socio-economic element and a<br />

tool of Moscow’s political interests. The security services maintain<br />

close links with organized criminal syndicates, whereby the<br />

criminals obtain enhanced protection and the espionage network<br />

gains intelligence and wider access in targeted states. The Kremlin<br />

benefits from organized crime to penetrate neighboring<br />

economies, judiciaries, and political systems, and to operate as a<br />

shadow intelligence agency. 26

INTRODUCTION | 23<br />

Informational<br />

11. Cyberspace Warfare: This includes systematic assaults and<br />

denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks on government sites by Kremlinorchestrated<br />

hackers, as witnessed in Estonia, Georgia, and<br />

Ukraine during their confrontations with Moscow. It can also<br />

entail the monitoring of telecommunications and infecting<br />

targeted networks with various viruses. For instance, in 2014 a<br />

Russian hacking group exploited a previously unknown flaw in<br />

Microsoft’s Windows operating system to spy on NATO,<br />

Ukraine’s government, and other national security targets. 27 The<br />

group has been active since 2009, according to research by iSight<br />

Partners, a cyber security firm. Its targets in the 2014 campaign<br />

also included a Polish energy firm, a Western European<br />

government agency, and a French telecommunications company.<br />

12. Trolling Offensives: The Kremlin recruits trolls either to write<br />

imaginary and inflammatory news reports or to disrupt the social<br />

media with provocative and disruptive comments. 28 The Kremlin’s<br />

“troll army” reportedly includes hundreds of paid bloggers who<br />

saturate Internet forums, social networks, and comments sections<br />

of Western publications with diatribes lambasting the West and<br />

praising Putin. Kremlin-sponsored youth groups are believed to<br />

fund online trolling activities. Following its attack on Ukraine,<br />

Moscow substantially increased its trolling offensives; Ukrainian<br />

news outlets have published long lists of people and sites that<br />

featured the activities of pro-Kremlin trolls.<br />

13. Propaganda Attacks: Russia’s “information offensive” or overall<br />

propaganda assault on the West is widely organized and well<br />

funded. During the Cold War, Soviet authorities used the term<br />

“active measures” to denote a combination of propaganda and<br />

action by the KGB to promote Moscow’s foreign policy objectives.<br />

Subversive propaganda seeks to create an alternative reality in

24 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

which all truth is relative and no information can be trusted,<br />

thereby disguising the facts about Moscow’s regional aggression<br />

against countries such as Ukraine. 29 Nonetheless, such attacks also<br />

have a simple underlying narrative: that the US is seeking to rule<br />

the world and only Russia can stop Washington’s drive for empire.<br />

This propaganda relies on four main tactics: dismissing the critic,<br />

distorting the facts, distracting from the main issue, and<br />

dismaying the audience.<br />

14. Media Controls: Moscow’s direct or indirect control over<br />

numerous television and radio outlets in Russia that broadcast<br />

programs to most former Soviet republics is a valuable instrument<br />

for influencing public opinion and political elites in neighboring<br />

states. This has been plainly evident in Belarus, Ukraine, and<br />

Moldova where a majority of citizens, and not only Russian<br />

ethnics, regularly watch and listen to the Moscow media, which is<br />

often more attractively packaged than local stations, in the form<br />

of “infotainment.” The lack of professionalism and a penchant for<br />

sensationalism in much of the local media has also assisted<br />

Moscow’s objectives in planting misleading information for<br />

political ends.<br />

15. Disinformation Campaigns: More systematic and pinpointed<br />

disinformation campaigns are conducted against particular<br />

governments, politicians, or pro-Western political parties in<br />

nearby states. They can also target Western ambassadors in<br />

Moscow or other capitals. Through its smear campaigns, Russian<br />

state propaganda often combines facts with cleverly disguised<br />

falsehoods. 30 Moscow’s message is given undue exposure due to an<br />

inability of some Western editors and journalists to distinguish<br />

between balance and objectivity, as well as the existence of a<br />

sizable constituency in the West, including businesspeople,<br />

academics, consultants, and journalists, whose jobs may depend<br />

on maintaining cordial relations with Russia. Disinformation can<br />

combine traditional media with the social media that help spread

INTRODUCTION | 25<br />

hoax stories. It taps into the widespread propensity in all societies<br />

for repeating and believing conspiracy theories, however<br />

outlandish.<br />

16. Media Manipulation: Russian outlets at home and abroad use the<br />

open Western media to create an environment favorable to<br />

Moscow by manipulating political and public opinion. This<br />

includes using intelligence operatives as journalists, bribing<br />

Western reporters, and presenting a diametrically opposed<br />

position to that of rivals to create the impression that the truth lies<br />

somewhere in the middle. For instance, Russian federal television<br />

and radio channels, newspapers, and online resources were<br />

employed in the concerted disinformation campaign against<br />

Ukraine in 2014–2015, in which the Kremlin denied any<br />

involvement in the war. Diplomats, politicians, political analysts,<br />

and representatives of academic and cultural elites supported this<br />

“disinformation front.” 31 The Kremlin media also exploit Western<br />

commentators to validate the regime’s messages. These “fellow<br />

travelers” fall into three categories: those who work or worked for<br />

the Kremlin but do not make their affiliations public; those who<br />

are apparently independent but support Russia’s policies; and<br />

those who may not support Moscow’s line, but whose words can<br />

be quoted in a way that appears to show that they do. 32<br />

17. Media Creation: Rival media outlets can be established in other<br />

states, including the television channel RT (formerly Russia<br />

Today), whose propagandists assert that the public is seeking an<br />

alternative and trustworthy source of information. The goal is to<br />

provide information and analysis that contrasts with the Western<br />

media, alleging that the latter is monolithic and serves government<br />

interests. 33 However, the stories covered are often skewered and<br />

incomplete in order to present Western officials in a negative light.<br />

The Kremlin has also enhanced its global outreach through its new<br />

Sputnik web and radio service that combines the print and

26 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

broadcast services of Voice of Russia with RIA Novosti. This<br />

propaganda outlet targets over 130 cities in 34 countries and will<br />

be available in at least 27 languages. All former Soviet republics<br />

will host a Sputnik hub that will broadcast in local languages and<br />

English. Moscow substantially increased spending for its foreignfocused<br />

media outlets for 2015, budgeting $400 million for its RT<br />

television channel and $170 million for Rossiya Segodnya, the state<br />

news agency that includes Sputnik News.<br />

18. Psychological Operations: Russia’s state-linked propaganda<br />

specializes in spreading confusion, fear, insecurity, panic, hysteria,<br />

and paranoia among targeted audiences abroad to deflate public<br />

morale, foster defeatism and demoralization, and reduce trust in<br />

national governments and international institutions. Propaganda<br />

can create uncertainty and ambiguity, thereby preventing any<br />

immediate response to Russia’s aggressive actions. As part of<br />

Moscow’s propaganda offensive to stoke fear and uncertainty<br />

along its borders, in June 2015 the Russian Prosecutor General’s<br />

Office was asked by Duma deputies from the ruling United Russia<br />

party to examine whether the independence of the three Baltic<br />

states was legitimate according to the Soviet constitution. 34 Such a<br />

move served to question the sovereignty of all former Soviet<br />

republics and to legitimize Russia’s interference in their domestic<br />

and foreign affairs.<br />

19. Disarming Opponents: “Psychops” can purposively inculcate<br />

cynicism among the audience, convincing them that no<br />

government is truthful and that the Russian and Western<br />

positions deserve equal treatment. The ultimate goal of all<br />

psychological operations is to influence political decisions in other<br />

countries and to undermine the will to resist or oppose Moscow’s<br />

policies. Russia’s informational wars are often geared toward<br />

“reflexive control,” in which under the influence of specially<br />

prepared information the adversary acts in a way that suits the

INTRODUCTION | 27<br />

Kremlin, whether the response is defensive or aggressive. In the<br />

domestic context, state propaganda may also encourage public<br />

passivity and fear, so that the Russian population does not<br />

challenge government policy. Psychops also manipulate and<br />

channel resentments and grievances inside Russian society toward<br />

Western scapegoats who are deemed primarily responsible for the<br />

country’s problems.<br />

Ideological<br />

20. Claiming Victimization: State propaganda depicts Russia as a<br />

victim of Western subterfuge and aggression and periodically<br />

heightens perceptions of threat and danger to confirm its<br />

assertions. Officials cultivate a sense of grievance and resentment<br />

against the West for Russia’s alleged humiliation after the Soviet<br />

collapse. 35 According to Moscow’s propagandists, the West either<br />

wants to eradicate Russia or to absorb it in the West: either way<br />

the purpose is to eliminate its uniqueness. Putin’s rule has ensured<br />

that Russia will no longer retreat while under pressure from its<br />

adversaries and will not succumb to destructive Western<br />

enticements couched as democratization and globalization.<br />

Victimization provides justification for the maintenance of a<br />

strong state and an authoritarian leadership that intends to restore<br />

the country’s military power, territorial reach, regional influence,<br />

and global ambitions.<br />

21. Alleging Encirclement: Russia is surrounded by ostensible<br />

enemies and needs to pursue an aggressive posture to combat<br />

them. Moscow claims that NATO and the EU are encircling the<br />

country, pushing it into a corner, and forcing it to lash out. In an<br />

elaborate justification for its attack on Ukraine in 2014–2015,<br />

Moscow charges that Washington organized the overthrow of the<br />

legitimate government in Kyiv primarily to create an excuse for<br />

reinvigorating NATO and deploying American forces closer to

28 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

Russia’s borders. In reality, NATO has been increasing its<br />

defensive presence in the region to deter Moscow’s escalating<br />

threats against Alliance members.<br />

Russia’s leaders also contend that the US uses “irregular warfare”<br />

such as NGOs and multinational institutions, including the IMF,<br />

to conduct “colored revolutions” and destabilize Russia’s<br />

dominions. The next stage planned by Washington is to foster<br />

conflicts within the Russian Federation by exploiting civil society,<br />

the liberal opposition, the mass media, and human rights groups,<br />

and by supporting Islamic insurgencies in the North Caucasus.<br />

The goal is to destroy Russia’s unity, capture its territory, and<br />

exploit its natural resources.<br />

22. Imagining Russophobia: Putin has made the struggle against<br />

“Russophobia” a cornerstone of his eclectic ideology, depicting<br />

Russians as an ostracized people despised by Western powers.<br />

Criticisms of Russian government policy by alleged Russophobes<br />

purportedly indicates a prejudicial disposition, a psychological<br />

illness, or a personality disorder. Some propagandists have sought<br />

to equate Russophobia with anti-Semitism thus depicting<br />

criticisms of Moscow’s policies as a form of racism, which should<br />

be internationally condemned and outlawed. Almost any incident<br />

that casts Russia in an unfavorable light can be depicted as<br />

motivated by Russophobia. Hence, Kremlin spokesmen have<br />

portrayed the shooting down of a Malaysian passenger plane over<br />

Donbas on July 17, 2015, by a missile fired from an area controlled<br />

by pro-Moscow rebels as a Western plot to discredit Russia.<br />

23. Russian Supremacism: Moscow’s imperial ambitions are<br />

undergirded by the concept of the “Russian World” (Russki Mir).<br />

According to this notion, all ethnic groups living on the territory<br />

of the former Soviet Union form part of a distinct multi-national<br />

entity and should be brought within the same state or multi-state<br />

union. Several categories of people are included in the “Russian

INTRODUCTION | 29<br />

World,” including ethnic Russians, regardless of where they live;<br />

Russian-speakers and alphabet users, regardless of their ethnicity;<br />

and “compatriots” and their offspring who have ever lived on the<br />

territory of the Soviet Union or even in the Russian Empire. 36<br />

Russian officials and the Kremlin’s ideological preachers<br />

frequently stress the manifest destiny of the allegedly unique<br />

Russian culture and the deeply spiritual “Russian soul” infused<br />

with a “special morality.” They deliberately ignore the deep<br />

demoralization evident in Russian society, as exemplified in its<br />

demographic trends including shorter life spans, declining fertility<br />

rates, and rising alcoholism. Russia’s alleged spiritualty is<br />

supposed to compensate for its economic failures.<br />

24. Russian Unification: The concept of a “Russian World’” is based<br />

on the assumption of a divided nation following the collapse of the<br />

Soviet Union. By promulgating Russian culture, education,<br />

language use, and political mobilization in neighboring states,<br />

Moscow tries to create the illusion in the West that these countries<br />

belong within Russia’s cultural and political space. Hence, the<br />

government is simply pursuing a natural course of unification.<br />

The Russki Mir concept has been introduced into several laws<br />

creating the legal basis for protecting compatriots abroad. One of<br />

the laws provides for the legal right to use Russian troops in other<br />

countries to actively defend these compatriots.<br />

25. Pan-Slavism: In Russia’s official version of history, Ukrainians<br />

and Belarusians are considered to be offshoots of the Russian<br />

nation. 37 This is based on the historically incorrect idea that<br />

Kyivan Rus (9 th to 13 th centuries AD) was a “Russian” state. In fact,<br />

there were no distinct Russians, Ukrainians, or Belarusians during<br />

that period in history but numerous East Slavic tribes and tribal<br />

unions. After the 14 th century, Muscovite Russians formed an<br />

enduring state entity that subsequently occupied Ukraine and<br />

Belarus for long periods and imposed the Russian language,

30 | <strong>EURASIAN</strong> <strong>DISUNION</strong><br />

church, and culture on the local populations. As a result, Moscow<br />

believes it has the right to control all the East Slavic peoples and<br />

those that are opposed are dismissed as traitors, as is the case with<br />

many Ukrainians since the Maidan revolution. Russian pan-<br />

Slavism is also extended by its proponents to include selected<br />

South Slavic and West Slavic groups by appealing to those<br />

nationalist elements that traditionally view Moscow as a protector<br />

and liberator from Turkic, Germanic, and other occupying<br />

powers. This often includes Serbia and Bulgaria.<br />

26. Religious Invocations: The Russian Orthodox Church is vocal in<br />

defending the allegedly endangered Christian Orthodox faithful in<br />

neighboring countries. It has a long tradition of serving as an<br />

instrument of government foreign policy before, during, and after<br />

the Communist interlude. The Moscow Patriarchate helps to<br />

maintain Russian influence within the former USSR among<br />

Orthodox believers and promotes anti-Western, illiberal, and<br />

anti-democratic values by stressing the divine nature of Russian<br />

nationalism and pan-Slavism.<br />

Putin has revived Joseph Stalin’s instrumentalization of the<br />

Orthodox Church and gained Patriarch Kirill’s blessing for his<br />

trans-national “Russian World” concept. 38 Moscow steers the<br />

Patriarchate to exert its influence in states such as Ukraine,<br />

Belarus, Moldova, and Georgia in order to maintain pro-Russian<br />

sentiments and undermine any autocephalous Orthodox<br />

Churches that support independence and disassociation from<br />

Russia. The Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox<br />

Church seeks to gather other Orthodox parishes under its<br />

jurisdiction. Many of these had transferred their allegiance from<br />

the Moscow Patriarchate to the Patriarchate in Constantinople<br />

after the Bolshevik takeover in 1917. Russian Orthodox churches<br />

have also been built or planned in several neighboring countries<br />

despite the misgivings of local officials. 39 These include a church<br />

in Tallinn, Estonia financed by sources linked to Vladimir

INTRODUCTION | 31<br />

Yakunin, head of Russian Railways, and a church in Macedonia<br />

funded by a Russian businessman.<br />

27. Revising History: To undergird its aim to rebuild a Greater Russia,<br />

Moscow is engaged in extensive historical revisionism. Statesponsored<br />

propagandists are rewriting the period of Soviet<br />

occupation as a progressive era of Russian benevolence rather<br />

than an era of retardation of Central and Eastern Europe’s political<br />

and economic development through the imposition of a failed<br />

ideology, a one-party dictatorship, and an incompetent economic<br />

system. Moscow also claims that the Cold War ended in a<br />

stalemate, rather than admitting that the failed Soviet system<br />

disintegrated from within and could not compete with a more<br />

dynamic West<br />

According to current historical rewriting, Russia naively tried to<br />

join the West during the 1990s but was rebuffed and ostracized. In<br />

reality, Russia failed to qualify for either EU or NATO<br />

membership because of its glaring inadequacies in the rule of law,<br />

democratic governance, and market competition, and its<br />

numerous conflicts with neighboring states. Officials contend that<br />

NATO and the EU captured the post-Communist countries when<br />

Russia was weakest, instead of conceding that these states were<br />

determined to join both institutions as protection against future<br />

empire building by the Kremlin. Distorted histories justify<br />

contemporary moves to revise borders and international alliances<br />