9 - NSF Digital Library

9 - NSF Digital Library

9 - NSF Digital Library

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

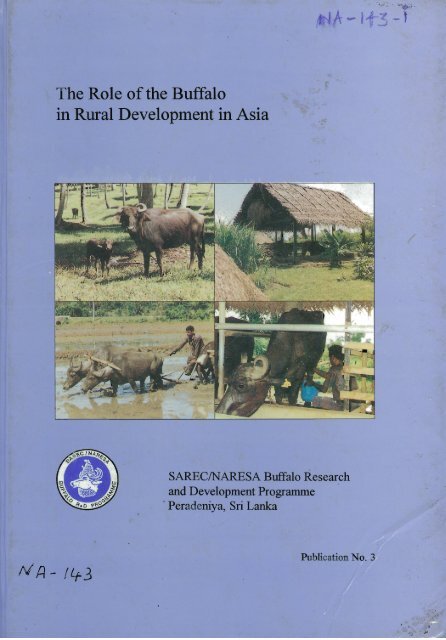

The Role of the Buffalo<br />

in Rural Development in Asia<br />

SAREC/NARESA Buffalo ~esearch<br />

and Development Programme<br />

Perzdeniya, Sri Lanka

ROLE OF THE BUFFALO IN<br />

RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN ASIA<br />

Proceedings of a Regional Symposium<br />

Organized by the Buffalo ~ese&ch Programme<br />

of the Swedish Agency for Research Cooperation with<br />

Developing Countries (SAREC) and the Natural Resources,<br />

Energy and Science Authority of Sri Lanka (NARESA)<br />

held 10-15 December 1995 in Peradeniya, Sri Lanka<br />

Edited by<br />

B.M.A.O. Perera<br />

J.A. de S. Siriwardene<br />

N.U . Horadagoda<br />

M.N.M. Ibrahun<br />

NARESA Press, Colombo, Sri Lanka

<strong>Library</strong> of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

SARECNARESA Regional Symposium on the<br />

Role of the Buffalo in Rural Development on Asia<br />

1995, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka<br />

Incudes bibiliographical references and index.<br />

ISBN 955-590-007-8<br />

1 .Buffalo- Regional Symposium. 2.Rural Development - Asia<br />

3. Buffalo - Rural Development I. Perera, B.M.A.O.<br />

II. Siriwardene, J.A. de S. Ill. Horadagoda, N.U.<br />

IV. Ibrahim, M.N.M.<br />

Proceedings of the SARECNARESA Regional Symposium on the<br />

Role of the Buffalo in Rural Development in Asia, held 1 1-15<br />

December 1995 Peradeniya, Sri Lanka<br />

O 1996 NARESA Press<br />

47/5 Maitland Place<br />

Colombo 7<br />

Sri Lanka<br />

ISBN 955-590-007-8<br />

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or<br />

transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical,<br />

photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written<br />

permission fiom the Publisher.<br />

Printed in Sri Lanka

Preface<br />

Despite the importance afthe buffalo in the rural economy of Sri<br />

Lanka, serious scientific attention was directed towards improving the<br />

productivity of this animal only after 1980, as a sequel to a national<br />

workshop organized under the sponsorship of the Swedish Agency for<br />

Research Cooperation with Developing Countries (SAREC). This<br />

workshop identiiied gaps in knowledge which hampered better utilization<br />

of this animal's potential. Subsequently, SAREC provided hnding<br />

through the Natural Resources, Energy and Science Authority<br />

(NARESA) for a five year research programme from 1983. During this<br />

first phase, 19 research projects were undertaken on hdarnental aspects<br />

of nutrition, reproduction, diseases and soci+econornics. The results<br />

were presented at a symposium held in Kandy in 1989. Subsequently,<br />

SAREC provided funds for a second phase comprising 34 projects<br />

covering a wide range of topics, including applied studies to develop new<br />

technologies to improve the productivity of buffaloes under rural farming<br />

conditions. This programme also contributed significantly towards the<br />

building up of it&astructure in the participating institutions and provided<br />

opportunities for postgraduate training of young researchers.<br />

Supplementary support was also provided to this programme by other<br />

donor agencies, chiefly the International Atomic Energy Agency<br />

(Vienna), the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research,<br />

the Overseas Development Administration of the UK and the<br />

Government of the Netherlands.<br />

In order to disseminate the knowledge gained and to transfer the<br />

technologies developed to the end-users (the village farmers), SAREC is<br />

now supporting a third phase of two years, during 1995 and 1996. The<br />

main objective of Phase 3 is to demonstrate the applicability and<br />

effectiveness of the new technologies and thereby popularize buffalo<br />

rearing through intensification of management practices. All activities of<br />

this phase are being conducted in close collaboration with the various<br />

institutions in the country dealing with research, education, training,<br />

extension and development relating to animal production and health.

This publication contains the r&earch papers presented by Sri<br />

Lankan scientists at a Regional Symposium on the Role of the Buffalo in<br />

Rural Development in Asia held in December 1995. Also included are<br />

keynote lectures delivered by seven eminent foreign scientists &om the<br />

Asian region and abstracts of some of the theses presented by<br />

postgraduate students who participated in the programme. The<br />

symposium provided an opportunity to review the work done under the<br />

second phase dthe SAREUNARESA buMo research and development<br />

pmgramme and to share experiences with leading scientists from Asian<br />

countries. It provided a f- far discussion of strateyges for<br />

dissemination of technical knowledge to rural farmers. A summary of the<br />

discussions together with conclusions and recommendations are also<br />

included in these proceedings.<br />

The project management team wishes to thank SAREC and<br />

NARESA for their excellent support, the scientists and collaborating<br />

institutes for their contribution to the programme, the innovative farmers<br />

who agreed to test the new technologies, and all those who helped to<br />

make this Symposium possible.

Preface<br />

OPENING SESSION<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Page<br />

Address by Project Representative - B.M. AO. Perera ix<br />

Address by Director General, NARESA<br />

- Priyani E. Soysa<br />

Address by SAREC Representative - AfhI Sher<br />

xii<br />

xiv<br />

Address by Hon. Minister of Science, ~ekhnolo~~ and<br />

Human Resources Development - Bernard Soysa<br />

xvi<br />

Vote of Thanks - H. Abeygunawardena xix<br />

GENERAL SESSION<br />

Buffalo production systems in South East Asia and possibilities I<br />

for transfer of appropriate teihnologies to improve<br />

productivity: an overview<br />

V. G. Momongan (Philippines)<br />

SARECJNARESA Project on Dissemination of information 19<br />

on improved buffalo production systems to small farmers<br />

JA. de S. Siriwardene<br />

SESSION I - PRODUCTION SYSTEMS AND USES<br />

Relevance and importance of crop-animal systems<br />

in Asia<br />

C. Devendra (ILRI, Kenya)<br />

The use of female buffaloes for on-farm work<br />

P. Bunyavejchewin, C. Chantalakhana<br />

(Thailand)<br />

1

Transfer of technology in smallholder intensive buffalo<br />

farming: Results &om a pilot study in Mahaweli<br />

System "H".<br />

H. Abeygunawardena, D.H.A. Subasinghe,<br />

A.h?l? Perera, S.S.E. Ranawana,<br />

M KA.P. Jayatilake, BM.A.0. Perera<br />

Supply response of milk and management dciency of 95<br />

cattle and buffalo production in Sri Lanka: A cross section<br />

study in wet zone and dry zone districts<br />

C. Bogahawatte<br />

A field survey and microbiological studies on Ruhunu curd<br />

K.K. Pathirana, C.P. Kodikara,<br />

D.KM.P. Dassanayake, S. Widanapathirana<br />

Preliminary analytrcal observations on persistence of milk<br />

yield in buffalo in Sri Lanka<br />

I.D. Sihra, A. Dangolla, K.F.S.T. Silva<br />

Factors affecting carcass and meat quality of indigenous<br />

buffaloes in Sri Lanka.<br />

H. JK Cyril, A. Jayaweera<br />

Panel Discussion<br />

SESSION I1 - GENOTYPES AND ENVIRONMENT<br />

Breeding strawes for optimum utilization of available<br />

resources in rural buffalo production systems<br />

C. Chantalakhana, P. Bunyavejchewin (Thailand)<br />

Physiological responses of Lankan buffaloes to stress<br />

at work<br />

A.A.J. Rajaratne, S.S.E. Ranawana<br />

Effectiveness of different cooling ireatments in alleviating<br />

heat load on water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis): A suitable<br />

cooling method<br />

E. R. K. Perera, A.N. F. Perera

Physiological responses of Lankan buffaloes to<br />

dehydration (Abstract)<br />

A.A.J. Rajaratne, S.S.E. Ranawana<br />

Panel Discussion<br />

New concepts and strategies in the utilization of<br />

fibrous crop residues (FICR) and agmindustrial by products<br />

(ABP) in buflFalo feeding<br />

N. V. Thu (Vietnam)<br />

Development of systems of supplementary feeding for<br />

buffaloes in Sri Lanka.<br />

S. Premarafne, P. Sivaram<br />

Composition of natural herbage and improvement of<br />

quality of some alternate feed sources for buffalo<br />

feeding<br />

A.N. F. Perera, E.R. K. Perera<br />

Serum concentrations of progesterone and its precursor<br />

cholesterol in buffaloes<br />

R. SivaRanesan, J.G.S. Ranasinghe,<br />

C. Mariathusan, H. Abeygunawardena<br />

Changes in growth, rumen characteristics and blood<br />

metabolites of indigenous buffalo heifers in response to<br />

supplementary feeding of urea treated versus untreated rice<br />

straw<br />

E.R.K. Perera. A.N.F. Perera<br />

Appropriate nutritional packages for smallholder buffalo<br />

production systems in Asia<br />

S.K. Ranjhan (India)<br />

Study of the grazing behaviour and forage utilization of<br />

fiee range buffalo herds<br />

H. Peiris. A. Perera<br />

273

The nutritional status ofindigenous buffaloes with 28 1<br />

respect to selected micronutrients (Abstract)<br />

SXE. Ranawana, J. Dhamardana,<br />

A. WAS. Abeysekara, A.A.J. Rajarame,<br />

G.D.J.K. Gunaratne, E.M.C. Ekanayake<br />

Panel Discussion ' 283<br />

SESSION IV - REPRODUCTION<br />

The importance of reproductive efficiency in successful 289<br />

buffalo dairy farming<br />

S. N. H. Shah (Pakistan)<br />

A comparative study of reproduction and productive 297<br />

characteristics of indigenous swamp and exotic river<br />

buffaloes in Sri Lanka.<br />

H. Abeygunawardensz, WD. Abayawansa,<br />

BM.A.0. Perera<br />

Seasonal variations in seminal and testicular 309<br />

characteristics in buffalo bulls<br />

D. Gunarajaingham, H. Abeygunawardena,<br />

K Y. Kuruwita, E.R.K. Perera, BM.A.0. Perera<br />

Effects of different suckling regimes on postpartum fertility 321<br />

of buffalo cows and growth and mortality of buffalo calves<br />

H. Abeygunawardena, V. Y. Kuruwita, BM.A.0. Perera<br />

Effects of exogenous hormones on fertility of postpartum 337<br />

anoestrous buffaloes<br />

H. Abeygunawardena, V. Y. Kuruwita, BMA.0, Perera<br />

Panel Discussion . ',' 351<br />

SESSION V - HEALTH AND DISEASES<br />

Disease preventioh and recent innovations in the control 355<br />

of bacterial and viral diseases of buffaloes<br />

D.K Singh (india)<br />

. .

Further studies on the epidemiology and immunology of 371<br />

haemorrhagic septicaemia in buffaloes<br />

M. C.L. de Ahvis, N. U. Horadagoda, T. G. Wijewardana,<br />

P. Abeynaike, A.A. Vipulmiri, S.A. Thalagoda<br />

Characterization of strains of buffalo calf rotavirus by 393<br />

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis<br />

U. Ariyaratne, S. Mahalingam<br />

Markers of idammation in buffalo milk<br />

I. D. Silva, K.F.S.T. Silva, A.P.N. Ambagala;<br />

R. Cooray<br />

Prevalence of leptospiral antibodies in buffaloes<br />

in Sri Lanka<br />

T. G. Wijewardana, B. D.R. Wijewardana,<br />

W.N.D. G.S. Appuhamy, K.R. KPM. Premaratne<br />

Observations on Schistosoma nmale RAO, 1993 427<br />

infections in the vertebrate and snail hosts<br />

D.J. Wezlgama<br />

Haematologcal and biochemical profiles of adult female 43 9<br />

Lanka buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis)<br />

N. U. Horadagoda, I.S. Gunawardena,<br />

A.P.N. Ambagala, DM.S. Munminghe<br />

"Domosedan" as a sedative analgesic in indigenous<br />

buffalo<br />

D.D.N. de Silva<br />

Functional efficiency of buffalo neutrophils<br />

I.D. Szlva<br />

Studies of Explanaturn (Gzgantocotyle) explanaturn 473<br />

infection: prevalence in cattle and buffaloes in Sri Lanka<br />

and pathology in natural infection<br />

I.S. Abeygunawardena, D.J. Veilgum4<br />

N. U Horadagoda, H.M.H.L. Jayapadma<br />

Panel Discussion<br />

vii

SESSION VI - CONCLUSIONS AND<br />

RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

APPENDICES<br />

Abstracts of TIreses<br />

Immunological response of buffalo cows to<br />

Toxocara vitulorum - antigenic analysis<br />

P. H. Amarasinghe<br />

Production systems and reproductive performance<br />

of indigenous buffaloes in Sri Lanka<br />

L.N.A. de Silva<br />

Studies on the composition of indigenous buffalo<br />

milk in Sri Lanka<br />

A. Horadagoda<br />

Immunopathological studies of Toxocara vitulorum<br />

in buffalo calves and rodents<br />

M.A. Masoodi<br />

Clinical and endocrinological studies on postpartum 509<br />

ovarian activity in Lanka buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis)<br />

V. Mohan<br />

Immunological response of bdalo cows and calves 51 1<br />

to Toxocara vintlonrm ,'<br />

R.P. KJ. Rajapahe<br />

Immunological responses of mice, rabbits and buffalo 513<br />

calves to Toxocara (neoascaris) vitulorum infection<br />

B.T. Samarasinghe<br />

Studies on rotavirus infedion of buffalo calves in Sri Lanka 515<br />

N.P. Sunil Chandra<br />

List of Participants 517<br />

Authors I nk 521

Welcome Address by Dr. Oswin Perera<br />

(Project Representative)<br />

Honourable Mr. Bernard Soysa, Minister of Science, Technology<br />

and Human Resources Development; His Excellency Mr. T. Akesson,<br />

Charge d AGkes for Sweden; Prafessor Priyani Soysa, Director General<br />

of the Natural Resources, Energy and Science Authority of Sri Lanka<br />

(NARESA); Dr. Afzal Sher, representative of the Swedish Agency for<br />

Research Cooperation with Developing Countries (SARECISida);<br />

distinguished keynote speakers, foreign and Sri Lankan guests,<br />

participants, ladies and gentlemen.<br />

On behalf of the Project Staff of the SARECMARESA Buffalo<br />

Research and Development Programme in Sri Lanka, it is indeed a great<br />

privilege and pleasure to welcome you most cordially to the opening of<br />

this Regional Symposium on "The Role of the Buflalo in Rural<br />

Development in Asia".<br />

The starting point of this programme was the holding of a<br />

National Workshop, in 1980, to review all aspects of buffalo research<br />

conducted up to that time, and to identify gaps in knowledge which<br />

impeded better utilization of this animal's potential by nual fanners.<br />

Based on the recommendations of the workshop, SAREC provided<br />

funding through NARESA for a five year research programme &om 1983.<br />

This fmt phase focused on fundamental aspects of nutrition,<br />

reproduction, diseases and socieeconornics. A large scale field survey<br />

was conducted to gather base-line information on the management and<br />

productivity of indigenous buffaloes, and a monograph, now recognized<br />

as the standard reference work, was published. Two buffalo research<br />

farms were also established.<br />

The results of these studies were presented at a symposium held<br />

in Kandy in 1989, and lead to a second phase in which SAREC provided<br />

funds for a further five year programme. This second phase included<br />

more applied studies to develop technologies which can be used at the<br />

field level to improve productivity under rural farming conditions.

In order to dissentinate the knowledge gained, and to transfer the<br />

technologies developed to the end-users (i.e. the village farmers), SAREC<br />

is now supporting a third phase of two years, during 1995 and 1 996. The<br />

activities being undertaken are five-fold. The first is establishment of<br />

Field Projects in villages, to demonstrate the applicability and<br />

effectiveness of the new technologies. Selected farmers in three regions<br />

are provided assistance and technical advice to upgrade their holdings to<br />

serve as "Model-farms". These farms will in turn serve as demonstration<br />

sites and training locations for other farmers. Secondly, a Buffalo<br />

Information Centre is being established, to serve as a repository and<br />

resource base for fbture research and development. Thirdly, a series of.<br />

Publications is under preparation, including a book for scientists and<br />

students, and a handbook for extension workers, to document and<br />

disseminate the scientSc, technical and practical knowledge that has been<br />

gained. Fourthly, a Public Awareness programme is being launched,<br />

through linkages with on-going agricultural programmes on television<br />

and radio, to broadcast the potential of the buffalo and to popularize<br />

buffalo farming based on sound principles. Finally, a programme of<br />

Continuing Education is being implemented, to update the knowledge<br />

and skills of farmers, extension workers, field officers and administrators<br />

in appropriate technologies which can maximize the utilization of this<br />

valuable livestock resource in rural development.<br />

AU these activities are conducted in close collaboration with the<br />

main governmental and non-governmental insbtutions responsible for<br />

livestock development in Sri Lanka. These include the Department of<br />

Animal Production and Health (DAPH), the Veterinary Research<br />

Institute 0, the Provincial Directorates of Livestock in the project<br />

locations, the National Livestock Development Board (NLDB), the<br />

Livestock Development Division of the Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka<br />

(MASL), the Coconut Triangle Milk Producers' Cooperative Union<br />

(CTMU), and the Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training<br />

Institute (KARTI). The project draws heady on the expertise of research<br />

workers at the University of Peradeniya and is coordinated by a small<br />

Secretariat.<br />

I also wish to gratefully acknowledge the supplementary support<br />

provided to the overall programme by other international and bilateral

donor agencies. Chief among these are the International Atomic Energy<br />

Agency (IAEA) in ~ienna, the Australian Centre for International<br />

Agr~cultural Research (ACIAR), the Overseas Development<br />

Administration (ODA) of the UK and the Government of the<br />

Netherlands.<br />

The Reg~oaal Symposium which we are here to inaugurate today<br />

has several objectives. It will critically review the work done under the<br />

second phase afthe SARECINARESA buffalo research and development<br />

programme, and share these experiences with eminent scientists in other<br />

Asian countries. It will also draw on their experiences in the application<br />

and dissermnation of technical knowledge to rural farmers in their own<br />

countries, and discuss strategies for wider application of selected<br />

technologies. Finally, it will identify potential areas for further study and<br />

technology transfer. Clearly, an important challenge for dI of us in the<br />

future is to develop innovative management packages, utilizing locally<br />

available resources, which will be sustainable under the more intensive<br />

land use systems that are evolving in most parts of the Asian continent.<br />

Ladies and Gentlemen, Thank you for your attention.

Address by Prof. Priyani E. Soysa<br />

(Director General, NARESA)<br />

Honourable Minister, Charge d Maires for Sweden, Dr. fial<br />

Sher, Dr. Abeygunawardena, Dr. Oswin Perera, researchers, guests and<br />

visitors. This seminar marks the termination of phase II of the SAREC<br />

Buffalo Research Programme and experts from the Asian region have<br />

been invited to review the research results and share their experiences.<br />

Research on the water b&do has been generously supported by SAREC<br />

since 1983. This aid which was channelled through NARESA, has<br />

amounted to nearly 75 million rupees over the past 12 years. SAREC has<br />

also provided assistance to the National Aquatic Resources Authority<br />

(NARA) and the Ruhunu University; the grand total being nearly a<br />

hundred million rupees. Sri Lanka is indeed grateful to Sweden for its<br />

interest in research in this country. The research programme had the<br />

support of a group of senior scientists from the University, the<br />

Department of Animal Production and Health and other agencies.<br />

Honourable Minister Bernard Soysa on assumption of duties questioned<br />

me on the progress of this research programme and also expressed his<br />

wish to share the results of research and the implications to the farmer<br />

with his colleague, the, Honourable Mr. Thondaman, Minister of<br />

Livestock Development and Rural Industries. The latter in turn was<br />

excited about the need of buffaloes for draught and now, in the<br />

development of milk production. Sri Lanka imports millions of rupees<br />

worth of milk food and I myself am concerned about this vast<br />

expenditure. How could the buffaloes help in this situation? Work has<br />

been done to improve the potential of the local buffalo breed by better<br />

efforts in reproduction, nutrition, reducing calf mortality and also<br />

morbidity among the adults of thls species.<br />

The research has produced a better understanding of viral,<br />

parasitic and other disease conditions that can be prevented and treated.<br />

Two research farms in Peradeniya and Narangalla have been developed<br />

to support research. These activities must now be taken over by either<br />

the W or the Department of Ammal Production and Health. Several<br />

young scientists have visited collaborating research institutes in Sweden<br />

thus helping Sri Lanka to build research capabilities and develop human

esources. The Project supported research training and the output fiom<br />

this exchange training programme was 8 PhD's and 17 Master's qualified<br />

scientists. The funding for research has now ceased and final reports<br />

were expected by end of September. SAREC is now funding Phase III of<br />

the project which amplifies the us~ess ofthe research and the need for<br />

dissemination of the research results. A buffalo infiation centre has<br />

been established for this putpose and recently we engaged the services of<br />

a consultant fiom Thailand to advice on setting up of tlus centre. The<br />

duration of third phase is two years. NARESA hopes that the<br />

Department of Animal Production & Health will maintain this centre<br />

thereafk. The exercise ofproducing information in the form of books for<br />

scientists and the handbooks and ledets for fatmer is in progress. The<br />

proceedings of thls workshop should be available in a few months,<br />

perhaps also incorporating the proceedings of a previous workshop held<br />

in 1988189. The farmers have to be appraised of useful scientific<br />

progress, brealang some ineffective traditional practices. The urea<br />

molasses mineral brick has been made available in the project areas, its<br />

usefulness has been demonstrated along with other intensive farming<br />

strategies to increase lactation. We have to learn lessons fiom India<br />

where milk is cheap and consumption is popular. In Sri Lanka milk is<br />

expensive and is becoming more and more expensive.<br />

We need to commercialize the production of the urea molasses<br />

nutrient brick. However, I understand that farmers outside the project<br />

area are also enthusiastically purchasing this brick. NARESA is now<br />

working with the National E n ~ Research ~ g Division (NERD)<br />

hopefilly to stimulate the commercial production of this brick.<br />

At this seminar participants should discuss whether the research<br />

has sigdicance for wider practical application and planned intervention<br />

for the greater good of our rural people. Perhaps the gaps in the local<br />

scientXc knowledge and research wil be filled by the exchange of ideas<br />

at this regional seminar. You have my best wishes for a lively exchange<br />

of views and I thank you for your patient hearing.

Address by Dr. Aha1 Sher<br />

(Representative, SAREC1Sida)<br />

Honourable Minister, Bernard Soysa, Director General<br />

NARESA, Professor Priyani Soysa, Charge d' Maires for Sweden, Dr.<br />

Perera, Dr. Abeygunawardena, distinguished scientists, ladies and<br />

gentlemen. I feel very honoured to be invited to address such a<br />

distinguished gathering at the opening ceremony of the regional<br />

Symposium on "the Role of Buffalo in Rural Development in Asia" a<br />

topic on which, I must confess, I am no expert. The Symposium<br />

programme reveals that some of the most eminent foreign scientists on<br />

the water buffalo will be sharing their experiences with the Sri Lankan<br />

counterparts.<br />

In the history of mankind, civilization has risen and fallen,<br />

cultures of great sophisbcation have developed in all continents.<br />

Societies offering great promise at one time have failed to sustain<br />

progress and turned into decay leaving behind only fragments of past<br />

glories. We marvel at the intricacy and the precision of the asterisk<br />

calendar and the wisdom of confucion. They represent cultural<br />

achievements of a society once at the forefront but now long since left<br />

behmd. Man has always been striving towards a better life but progress<br />

has been uneven to say the least. In many instances, changes for the<br />

better come to a halt or even regress. What are the driving forces behind<br />

progress and why some cultures are unable to sustain forces of progress<br />

remains to be a question. There are many theories. Some authors<br />

associate strong religious and ideological influences associated with<br />

stagnation and decay, while others would rather interpret the fall of<br />

mighty powers as a consequence of expressive exploitation of scarce<br />

resources, human or material as the case may be. I would like to argue<br />

that science in general and basic sciences in particular have been and<br />

must c&dy continue be the decisive factor for achieving development.<br />

This is in no way an original idea but it has often been forgotten in the<br />

context of aid for developing countries. Before proceeding on to matters<br />

of th~s Symposium, let me say a few words regarding this SIDA-SAREC<br />

confusion. SAREC was an independent research financing agency of<br />

Sweden created in 1975 under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As of 1 st

July 1995, the Swedish government decided to merge all the five Swedish<br />

aid agencies into one agency. SIDA that is familiar to you is written in<br />

capital letters, but the new agency is also called Sida, with only the first<br />

letter in capital. More importantly, it represents a completely different<br />

agency. The earlier SIDA was the Swedish International Development<br />

Authority, but the new agency created by merging all aid agencies is<br />

referred to as the Swedish International Development Cooperation<br />

Agency.<br />

Most of you are aware that SAREC has supported the buffalo<br />

research programme since 1982. In 1994, when I participated in a<br />

discussion with the water buffalo research and advisory committee, it was<br />

mentioned that dumg the 10 years of research, some 90 research projects<br />

on different aspects of the water buffalo were approved. Apart from<br />

creating a conducive research environment and establishing the necessary<br />

inikastructure the project has trained a good number of researchers. There<br />

has been 8 PhD and 17 MSc programmes completed and some 100<br />

scientific papers published. Thus it was suggested that the programme<br />

should now enter into a phase of dissetllination of information. The water<br />

bufMo research committee thus proposed to SAREC that a final two year<br />

grant be awarded to the programme with the main aim of (a) halising<br />

the ongoing research projects, and (b) translating the results and<br />

knowledge gained into practical recommendations and guidelines which<br />

shall be transferred to implementing agencies and fanners through<br />

workshops, publications and comprehensive programme reports. This<br />

Symposium is a link in the chain of activities to achieve the aim, I just<br />

mentioned. I hope the result of this programme can be implemented for<br />

the development and prosperity of the Sri Lankan people. I would also<br />

take this opportunity to congratulate the Water Buffalo Research Team,<br />

NARESA, Mr. Asoka de Silva, the former Deputy Director General of<br />

NARESA who was attached to this programme right from its inception,<br />

my predecessor Carl Guvtsson Thormstorm and all those people who<br />

have worked very hard to make this programme a success. As I am<br />

aware that you have a tough schedule ahead of you, I would not like to<br />

take more of your valuable time. I wish you all the best in your<br />

Symposium and may God bless you.

Address by Mr. Bernard Soysa<br />

(Hon. Minister for Science, Technology and Human<br />

Resources Development)<br />

Madam chairperson, professors, research workers distinguished<br />

visitors, ladies and gentlemen, as mentioned by the Director General of<br />

NARESA, this particular project with regard to the buffalo was one that<br />

was pointed out to me as of great importance when I assumed duties as<br />

minister one year ago. It is true that the importance of the buffalo in the<br />

rural economy of this country has not been appreciated over the years.<br />

Even farmers fail to appreciate the role of this animal in their own lives<br />

in sdlicient measure. The replacement of the buffalo with the tractor was<br />

resisted by the farmer not due to any set of causes but due to the normal<br />

conservatism of the rural people. I remember when the late Mr. Philip<br />

Gunawardena was Minister of Agriculture, in his attempts to reorganise<br />

paddy cultivation in this country, he brought forward the paddy lands bill<br />

that required the participation of the cultivating peasants in managing<br />

rural committees. There was some dificulty in getting fanners to a<br />

operate and accept this new structure. As you are aware, this was an<br />

attempt to cut across the semi-feudal relationships which existed with<br />

regard to land holdings and cultivation under the "Ande' System". It was<br />

difficult to persuade the cultivators. I remember a very enthusiastic fiend<br />

of mine and I attempted to convert the rural people in Tissamaharama to<br />

accept this new structure and participate in the committees. We told<br />

them that they could pool their resources to buy a tractor, but the<br />

response was "why do we need a tractor, we have the buffalo". My fiend<br />

argued for half an hour to try to prove to them the superiority ofthe<br />

tractor. The peasants were unconvinced and one of them said he would<br />

think about it and come back the next day with h~s answer. When we<br />

met him the next day his face was alight and he said he had the answer<br />

to all the arguments, which was that the tractor cannot be bred, and<br />

therefore the buffalo was superior. While rice fanners were prepared to<br />

defend the bdMo not much has been done to preserve the buffalo in the<br />

economy. The use ofthe buflFalo is known to them but not the care of the<br />

buffalo in the same way. I was discussing this matter with a person fiom<br />

the AMUL Project in India which has been so very successful in<br />

increasing milk production. He admitted that the availability of

traditional grazing land for the .buffalo in India too is diminishing.<br />

~rtificid feeding and other innovations had to be devised. He said that<br />

if that is the problem facing India, it is bound to be a prpblem in Sri<br />

Lanka too. If we are to face such a problem then what are the answers?<br />

A research output of the SAREC/NARESA Project is the use of the urea<br />

molasses mineral brick. We have been trpg to persuade the Minister of<br />

Livestock Development to by to sponsor its commercial production<br />

through involvement of the private sector. There are many other aspects<br />

for which the biotechnologist must find solutions. The whole question<br />

of upgrading the local buffalo with imported buffalo breeds have been<br />

tried several times. I do not know how far the experiments have<br />

succeeded. I am told that in order to increase the productivity of the<br />

buffalo, attempts have been made to use artificial insemination and that<br />

so far it has not proved to be successful. Therefore the whole question of<br />

how to save the buffalo is still a bang problem. We need to share our<br />

experiences in Asia because Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Burma, India<br />

and Palastan have the buffalo as a very important element in the economy<br />

of those countries, particularly to the agricultural economy and therefore<br />

if we pool the research done in all these countries, I am sure we can<br />

benefit by one another's experiences.<br />

- ~<br />

The problems may not be the same in each country but while<br />

variations exists, these can be understood and appropriate measures<br />

adopted. The important work that you have t do is to share the<br />

experiences during the course of this Symposium. % do.not want to say<br />

much more because my bowledge on the buffdo is ext&mely limited.<br />

My acquaintance with the buffalo has not always been a very pleasant<br />

one. When I have attempted to cross fields and go up mountain sides,<br />

even up Piduruthalagala, I have had most hostile encounters with the<br />

buffalo. However, I do not bear a grudge against the animal on that<br />

account but the fact remains that I am not competent to speak about its<br />

welfare or what is required for the development of the buffalo here. I<br />

leave that to the scientists who have been working in +e field; I wish<br />

your cooperative efforts in sharing knowledge will prove beneficial not<br />

only to Sri Lanka and the rural population of this country but also to<br />

neighbowing countries as well. I am happy that as a minister I was asked<br />

to come to the inauguration of deliberations today, to see what can be<br />

done at the Ministerial level' to help you to get the necessary collaboration

with other people and to see that where there is any lack of resources that<br />

might be rectified. On that score as far as the ministry is concerned, I am<br />

very happy to see that organisations such as NERD and NARESA which<br />

are under my ministry have stepped into the programme and are prepared<br />

and anxious to ceoperate in getting this project going. I wish your<br />

deliberations every success and tmst that at the end of the deliberations<br />

we will have a situation where everydung has not gone up in hot air and<br />

discussion, but implementation may be possible through some<br />

collaborative mechanism which can bring the cultivating peasants into<br />

the programme, without whom all such discussions would be futile.<br />

The dichotomy between research and implementation is a very<br />

dangerous one; we can have a lot of valuable research whlch remains<br />

barren because it is not implemented. Therefore the question of how to<br />

translate the valuable results of research into practical implementahon<br />

mechanisms at the grass roots level is a problem. However, I think it is<br />

necessary for SAREC and NARESA to give their minds along with<br />

scientists to the problem of bridging this gap and allowing the peasant to<br />

come on to the information highway of today. This is all I have to say to<br />

you, I wish your deliberations all success and I want to thank NARESA<br />

and SAREC for inviting me to come here today and may your<br />

deliberations bring fnutful results for all countries concerned. Thank you<br />

very much.

Vote of Thanks by Dr. H. Abeygunawardena.<br />

Distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, it is my pleasure to'<br />

propose a vote of thanks on behalf of the Organizing Committee of this<br />

Regional Symposium. Mr. Bernard Soysa, the Honourable Minister for<br />

Science, Technology and Human Resources Development, we are most<br />

gratefid to you Sir, for accepting our invitation to grace this occasion,<br />

amidst a very busy schedule. Your Excellency, Charge dl Maires for<br />

Sweden, thank you very much for being with us at the opening of this<br />

Regional Symposium. Professor Priyani E. Soysa, the Director General<br />

of NARESA, we wish to thank you madam, for the constant<br />

encouragement and stimulation extended towards the staEof the buffalo<br />

research programme in organizing this symposium.<br />

I wish to thank you all for accepting our invitation and being<br />

present with us this morning. Your presence is indeed a great source of<br />

encouragement and inspiration. Despite the importance of the water<br />

buffalo in rural farming communities, this species had not received<br />

indepth scientific investigations in Sri Lanka until SAREC sponsored a<br />

comprehensive research programme which commenced in the early<br />

1980's. We wish to acknowledge the generous contribution of SAREC<br />

and it is a pleasure to have with us today, Dr. A hl Sher and Dr. Ronnie<br />

Duel, the representatives of SAREC. We are also pleased to have in our<br />

midst Professor Ingemar Settergren from Sweden who has been<br />

associated with this programme as a reviewer and promoter from its<br />

inception.<br />

On behalf of the organizing committee, I wish to express our<br />

gratitude to all the eminent scientists from the Region and the<br />

representatives of international agencies for accepting our invitation and<br />

being present here with us. We are certain that you will inspire our<br />

researchers by sharing your experiences and play an important role<br />

during the discussio& and in the formulation of future research<br />

drections.<br />

I wish to acknowledge the cooperation extended by the<br />

Department of Animal Production & Health, National Livestock

Development Board, the Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka, University of<br />

Peradeniya, Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training<br />

Institute and the Coconut Triangle Milk Producers Union, to the buffalo<br />

research programme and in organizing this symposium. I also wish to<br />

express our gratitude to the commercial organizations who have<br />

contributed in various ways towards the symposium. A special word of<br />

thanks to the Difector of the Plant Genetic Resources Centre (PGRC) and<br />

his stsfor providing this excellent facility for the symposium.<br />

The current phase of the BuflFalo Research Programme, as<br />

mentioned earlier is pnmanly aimed at disseminating information and we<br />

are indebted to the participating scientists, fanners, extension workers,<br />

research and technical assistants for their cooperation. We are optimistic<br />

that our untiring efforts will succeed in delivering the new knowledge to<br />

the end-user, the rural fanner.

BUFFALO PRODUCTION SYSTEMS IN SOUTH EAST<br />

ASIA AND POSSIBILITIES FOR TRA<strong>NSF</strong>ER OF<br />

APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGIES TO IMPROVE<br />

PRODUCTIVITY: AN OVERVIEW<br />

V.. G. Momongan<br />

Institute of Animal Science, College of Agriculture<br />

University of the Philippines at Los Bailos<br />

College Laguna 4031<br />

THE PHILIPPINES<br />

Abstract: Swamp buffaloes which are predominant in Southeast (SE) Asia are<br />

raised by smallholder farmers primarily for draught. Buffalo production in SE<br />

Asia has always been an integral component of crop production. While 96.5%<br />

of the world buffalo population are in Asia, only 12% are in SE Asia.<br />

Decreasing trends in buffalo populations are occurring in Brunei, Malaysia,<br />

Philippines and Thailand. Increasing trends in the use of tractors to replace or<br />

combine with buffalo draught power are occurring throughout SE Asia.<br />

Thailand and Indonesia had 337% and 279% increase in the number of tractors,<br />

respectively, in 1993 compared to that in 1979-8 1. Inspite ofthe increasing use<br />

of the tractor for tillage, buffalo is predicted to remain with smallholder farmers<br />

in SE Asia because of distinct advantages appreciated by farmers.<br />

The different buffdo produdion systems are briefly discussed. Buffalo<br />

beef production had increased substantially in 1994 compared to that during<br />

1979-81, contributing 26% of the total beef production in Asia and SE Asia.<br />

However, the contribution of buffalo beef to total meat production was very<br />

small, indicating a tremendous potential for the buffalo meat to take a greater<br />

share of the market for meat products. The contribution of buffalo milk to total<br />

milk production was 40% in Asia and only 11% in SE Asia, supporting the<br />

observation that swamp buffaloes are not primarily used for millcing.<br />

Appropriate technologies to improve the productivity of swamp buffaloes are<br />

also discussed.<br />

Keywords: Buffalo, production systems, SE Asia, appropriate techuologies,<br />

productivity.

Buffalo production systems in South East Asia<br />

The predominant water buffalo in Southeast Asia is the swamp type,<br />

of which 95 to 99% are raised by smallholder farmers as an integral part<br />

of their farming system. In Thailand, the smallholder farmer usually has<br />

1 - 3 b&oes per household (Konanta and Intaramongkol, 1994); in Lao<br />

PDR, 2 - 4 buffaloes (Bouahom, 1994); in the Philippines, 1 - 2<br />

carabaos; and in Indonesia, it ranges fiom 2 (Central Java) to 14 (South<br />

Sulawesi), with a mean of 6 buffaloes per family (Toelihere, 1980). In<br />

Vietnam, 1 - 2 buffaloes are kept per family in the delta areas and 5 - 7 in<br />

the central highlands (Cuong and Hien, 1989). Farmers regard the<br />

baa as a fm of security which can be sold when there is a dire need<br />

for cash.<br />

Most of the swamp buffaloes are raised primarily for draught, and<br />

secondly, for meat and milk. In the Philippines, 99% are raised by<br />

smallholder farmers mainly for draught purposes. In Vietnam, 97% are<br />

kept by smallholder farmers (Nguyen et al., 1994), and 65 to 68% of the<br />

total buffalo population are draught animals (Cuong and Hien, 1 989). In<br />

Lao PDR, about 95% of the traction power for land preparation in rice<br />

cultivation comes from bdhlo (Ebuahom, 1994). Buffaloes are also used<br />

for transport in pulling carts, sledges, bamboos or logs; for riding or as<br />

pack animals; aad in extracting juice fiom sugar cane, or in lifting watef<br />

for irrigation.<br />

Ofthe 148.8 million buffaloes in the world, 96.5% a 143.6 million<br />

are in Asia. However, only about 12% a 17.9 million are in Southeast<br />

(SE) Asia (Table 1). The buffalo populations in Bmei, Malaysia,<br />

Philippines and Thailand have decreased compared to their respective<br />

populatians in 1979-81. Those in the rest of the SE Asian countries<br />

showed an increase, with Cambodia and Lao PDR registering 120% and<br />

57% increases respectively, over the last 15 years. Also, the least number

V. G. Momongan<br />

of people sharing a b&alo is in Lao PDR, Cambodia and Thailand with<br />

about 4, 12 and 14 peoplehuffalo, respectively. Although the buffalo<br />

population in Indonesia had increased by 42.8% in 1994 and ranks<br />

second in SE Asia, yet the number of people sharing per buffalo<br />

(55.4huffalo) is even greater than that in Brunei (28huffalo). Malaysia<br />

had the greatest number of people per buffalo, at 106 personslb&alo.<br />

Table 1. World, Asian and Southeast Asian human and buffalo<br />

populations.<br />

Geographical 1994 Popln. No. of % Change in<br />

locations (x 1,000) people per buffalo popln.<br />

buffalo 1994 over '79-'8 1<br />

Human Buffalo<br />

World 5,630,240<br />

Asia 3,333,188<br />

SE Asia 474,978<br />

Brunei 280<br />

Cambodia 9,868<br />

Indonesia 194,6 15<br />

Lao PDR 4,742<br />

Malaysia 19,695<br />

Myanmar 45,555<br />

Philippines 66,188<br />

Singapore 2,821<br />

Thailand 58,183<br />

Vietnam 72,93 1 3,009 24.2 +30.20<br />

Adapted from: 1994 Production Yearbook (FAO, 1995)<br />

BUFFALO PRODUCTION SYSTEMS<br />

In general, buffalo raising in SE Asian countries is not<br />

considered a distinct enterprise, but has always been an integral part of<br />

the crop production system in smallholder farms. Buffaloes provide<br />

&au&t power and manure for maintaining soil fertility and utilize crop

Buffalo production systems in South Emt Asia<br />

residues and farm by-products as feeds. Only in few areas can you find<br />

buffdoes being raised for milk or meat production as the primary<br />

concern. In most cases, buffalo meat is considered a by-product of the<br />

draught or milking animal. Milk is obtained mainly for consumption in<br />

the locality.<br />

Draught Buffalo Production<br />

Production of draught buffalo is mostly associated with rice<br />

farming systems, especially in rain-fed rice paddies, although they are<br />

utilized also in other types of farming systems, such as sugar cane,<br />

coconut, cnl palm and other upland crops or a combination thereof. In the<br />

Philippines, a carabao is used for 84 working days annually, although in<br />

rice-based farming systems carabaos work for 98 days yearly (Alviar,<br />

1986). Thai buffaloes work 20 - 146 days yearly (Chantalakhana and<br />

Bunyavejchewin, 1989). In Vietnam, buffaloes work for 3 - 4 months<br />

yearly in mountainous areas and 5 - 6 months in the delta region (Cuong<br />

and Hien, 1989).<br />

In recent years in SE Asia, there has been a slow increase in farm<br />

mechariization replacing the draught buffalo. There was an increase of<br />

138% in the number of tractors in 1993 .compared to that in the 1979-81<br />

period, although, the increase in areas cultivated with rice was only about<br />

12% over the same period oftime (Table 2). hdonesia and Myanmar had<br />

the highest increase in land area under rice while Philippines, Lao PDR<br />

and ~ala~sia showed a decrease in land area under rice in 1993<br />

compared to that in 1 979-81.<br />

Thailand had the highest increase in the number of tractors<br />

(336.7%) in 1993, followed by Indonesia (278.7%), compared to those<br />

in the 1979-81 period. Bunyavejchewin et al. (1 994) reported that some<br />

of the farmer's primary reasons for purchasing tractors to replace or<br />

combine with buffalo draught power were: (1) speed in tillage, (2)<br />

suitability for pl-g clay sod, (3) shortage of family labour due to the<br />

migration of working age members of the family to industrial cities, and

Table 2. Changes in the hectarage planted with rice in relation to the changes in the number of tractors and buffalo<br />

population in the World, Asia and Southeast Asia.<br />

Geographioal Changes in area planted with Changes in the number of tractors and buffaloes in 1993<br />

locations rice in 1993 over 1979-81 over 1979-81<br />

Tractor Buffalo<br />

Area (1 000ha) % No. % (1 000 head) %<br />

World<br />

Asia<br />

SE Asia<br />

Brunei<br />

Cambodia<br />

Indonesia<br />

Lao PDR<br />

Malaysia<br />

Myanmar<br />

Philippines<br />

Singapore<br />

Thailand<br />

Vietnam +92 1 +16.5 +14,172 +62.1 +646 +28.0<br />

Adapted from: 1994 Production Yearbook (FAO, 1995)<br />

U<br />

f<br />

P

Buffah production systems in South East Asia<br />

(4) as a means for quick transportation. However, buEalo raising will<br />

still remain an integral part of the farming systems of the smallholder<br />

fmers because of some of the advantages the farmer derives in keeping<br />

buflFaloes. A mature buffalo may void 5-7 MT of fresh manure per annum<br />

which could fkhlize the soil. Raising buffaloes will not entail extra<br />

expense to the fanner but may even help to utihze excess family labour<br />

and farm waste products more efficiently. Moreover, even with the use<br />

of a hand tractor for tillage, the buffalo is still used to plough the rice<br />

paddy close to the dike. Management of buffaloes under rice-based<br />

fkmhg systems is considered a very simple, less strenuous task and it is<br />

usually assigned t o w members like children, women or old folks who<br />

cannot do hard work. The buffaloes are tethered and allowed to graze<br />

along roadsides, vacant lots or communal grazing lands and in paddy<br />

fields after the harvest of primary or secondary crops, to utilize rice straw,<br />

corn stover, groundnut hay, soybean hay and other fodder or grasses as<br />

feed.<br />

In coconut, oil palm or sugar canebased farming systems,<br />

buffaloes are used to transport coconuts, bunches of fiesh hit, oil palm<br />

nuts or sugar cane stalks to loading areas. Castrated bulls are usually<br />

preferred for such tasks because of their size, strength and docility. In<br />

Thailand, buffalo bulls are usually castrated at the age of 2.5 to 3.0 years<br />

(Chantalakhana and Bunyavejchewin, 1989); and in the Philippines, at<br />

amean age of 3.3 years with a range of 1.8 - 4.8 years (De Guzman and<br />

Pereq 1981 cited by Momongan, 1992). When not used for work,<br />

buffaloes are tethered or allowed to graze under coconut or oil palm trees.<br />

Under sugar cane-based farming systems, buffaloes are tethered under<br />

trees or under shelter and fed with sugar cane tops or young sugar cane<br />

plants or other crop residues.<br />

Mating occurs in communal grazing areas, usually after the crop<br />

harvest. As a result the farmer may not know which buffalo bull mated<br />

the cow. With the onset of the rainy season when the paddy fields are<br />

prepared and planted for the next cropping season, the buffaloes are tied<br />

near or under the house of the farmer and fed rice straw or freshly-cut<br />

grasses. Concentrate supplements are not normally given, except table

V.G. Momongan<br />

or mineral salts. Occasionally, rice bran or other farm by-product<br />

concentrates may be given especially to the nursing or milking dam.<br />

The health care for buffaloes is minimal. Farmers do not buy<br />

vaccine to vaccinate their buffaloes, especially against haemorrhagic<br />

septicemia and foot and mouth disease. They depend on the free<br />

vaccination program of the government which is not conducted regularly.<br />

Dew&g of bufFalaes is not normally performed by farmers, resulting<br />

in high calf mortality which may range from 10 to 40%. Weaning of<br />

calves is not usually done and it is not uncommon to see a one year old<br />

calf by the side of its dam.<br />

Buffalo Meat Production<br />

Traditionally, when the buffalo is no longer fit for draught or for<br />

milk production, the animal is slaughtered for meat. The meat fiom such<br />

carcasses is tough and fibrous, and the dressing percentage varies fiom<br />

40 - 50%. This is the reason why some consumers consider buffalo beef<br />

inferior to bovine beef However, if the buffalo is slaughtered at a young<br />

age similar to that of cattle, the quality of buffalo meat is just as good as<br />

beef (Calub et al., 1971; Joshi, 1988; Ibarra, 1988; Zava, 1991; Oliveira<br />

et al., 1991).<br />

In general, the total buffalo beef production increased<br />

substantially in 1994 compared to that during the 1979-81 period by<br />

67.2% in Asia and 22.4% in SE Asia. However, in terms of buffalo beef<br />

per caput, the figure in SE Asia decreased (-7.5%), while that in Asia<br />

increased by 3 1.5% (Table 3). Ifwe examine the trend in consumption<br />

in various SE Asian countries, buffalo beef per caput in 1994 increased<br />

in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Philippines and Vietnam; and decreased in<br />

Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand as compared to their<br />

respective figures in 1979-81.<br />

Table 4 shows the percentage of buffalo'beef production to the<br />

total beef production in 1 994.

Table 3. World, Asia and Southeast Asia buffalo beef production and human population in 1994 in relation to<br />

production and human population in 1979-81.<br />

Geographical Human popln. Total buffalo Buffalo beef Human poph. Total buffalo beef Buffalo<br />

looations in 1980 beef prodn. in availability in 1994 prodn. in 1994 beef<br />

(x 1000) 79-81 per caput (x 1000) (x 10OOMT)<br />

per caput<br />

World<br />

Asia<br />

SE Ash<br />

Bmei<br />

Cambodia<br />

Indonesia<br />

Lao PDR<br />

Malaysia<br />

Myanmar<br />

Philippines<br />

Singapore<br />

Thailand<br />

Vietnam<br />

Adapted from: 1994 Production Yearbook (FAO, 1995)

Table 4. World, Asia and Southeast Asia buffalo beef and bovine beef<br />

production in 1994.<br />

Geographicai . Beef production<br />

looations<br />

Buffalo Cattle Total beef Percentage of<br />

( l0fJOM-p ---------------<br />

----------- X buffalo beef<br />

World<br />

Asia<br />

SE Asia<br />

Brunei<br />

Cambodia<br />

Indonesia<br />

Lao PDR<br />

Malaysia<br />

Myanmar<br />

Philippines<br />

Singapore<br />

Thailand<br />

Vietnam 94 79. 173 54.3<br />

Adapted ftom: 1994 Produotion Yearbook (FAO, 1995)<br />

WMe buffao beefacmmted fix only 4.8% ofthe total beef production in the<br />

world, in Asia and SE Asia, the figure was 26%. Tn Lao PDR and Vietnam,<br />

buffalo meat accounted for more than 50% of the total beef production in<br />

1994 and about one-third of the beef production in the Philippines and<br />

Cambodia However, the percentage of buffalo beef to the total meat<br />

production is very small (Table 5), indicating a tremendous potential for the<br />

buffalo meat to increase its share of the market fix meat products. With<br />

increasing use of tra&ns in place of draught buffaloes, more animals may be<br />

available for buffalo meat production.<br />

In SE Asian countries, there are isolated cases where buffaloes are<br />

raised pnrmmly for meat. In Indonesia, this occurs mainly in the marshland<br />

of Kalimantan where. they multiply naturally. The animals are caught only

~<br />

Table 5. World, Asia and Southeast Asia buffalo beef production in relation to total meat production and human<br />

population in 1994. 9 F<br />

Geographical Human popln. Total meat pro& Total buff. beef prodn. Total meat per caput % buffalo beef b<br />

locations (x 1000) (x 1000 h4T) (X 1mM'n ('kg) to total meat 8 4<br />

s<br />

World<br />

Asia<br />

SE Asia<br />

Brunei<br />

Cambodia<br />

Indonesia<br />

Lao PDR<br />

Malaysia<br />

Myanmar<br />

Mppines<br />

Singapore<br />

Thailand<br />

Vietnam 72,93 1 1,256 94 17.22 7.49<br />

Adapted fiom: 1994 Production Yearbook (FAO, 1995)

V.G. Momongan<br />

when they are ready to be marketed for meat. Also, in Tana Toraja, Central<br />

South Sulawesi, the piebald or black and white buffalo is kept only for meat<br />

production and slaughtered at traditional burial ceremonies (Satari et al.,<br />

1994). Tn Brunei, the swamp buffalo is mainly used for meat and in limited ,<br />

cases, for work (Cho, 1981). The average liveweight of the mature Brunei<br />

buffalo is 401.2 2 49.9 kg (range: 259-450 kg). Most of these buffaloes are<br />

to be found in the districts of BruneiMuara (62%) and Tutong (30%) .<br />

Buffalo Milk Production<br />

More than 40% ofthe miJk in Asia comes fiom water buffalo (Table<br />

6). However, in SE Asia, buffalo contributes only about 11% to the total<br />

milk production, supporting the observation that swamp buffalo is not<br />

normally milked but primarily raised as a draught animal. Most of the milk<br />

obtained in SE Asia comes fiom river type buffaloes. In Malaysia, the entire<br />

river type buffalo population is dned to Perak and Selangor, the animals<br />

are mostly owned by Indian fanners and the, average herd size being 5-25<br />

animals (Jainudeen, 1989). In the Philippines, buffalo milk production is<br />

mainly hm Murrah and river-swamp crossbreds which are dned in the<br />

provinces of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Rizal, Pampanga and Laguna, and<br />

contributed about 52% ufthe 29,000 MT of milk produced in 1994. Buffalo<br />

milk contributed more than 40% to the total milk production in Vietnam<br />

while Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDR do not produce substantial<br />

amounts of buffalo milk.<br />

Studies showed that Murrah-swamp crossbreds produce<br />

significantly more milk than the swamp type buffalo (Yongzuo and<br />

Weiming, 1991 ; Momongan et al., 1994; Ly, 1994; Shrestha and Parker,<br />

1 994).<br />

TECHNOLOGIES TO IMPROVE PRODUCI'IWIY<br />

It has been the common observation that the swamp type buffalo has<br />

low productivity, particularly in its reproductive efficiency. It is known to

Buflalo production systems in South East Asia

V. G. Momongan<br />

be late maturing, with a low pregnancy rate and calf crop, long service<br />

period and calving interval, and low milk production. Many of these<br />

productivity traits are iduenced by the management systems. Research<br />

has shown that proper selection of breeding animals, nutrition, and care<br />

and management can improve rate of growth, attainment of sexual<br />

maturity, conception rate, postpartum ovarian activity and milk<br />

production.<br />

Nutrition<br />

Pt'iany of the buffaloes under the care of smallholder farmers are<br />

fed with low quality roughages and farm by-products (rice straw, corn<br />

stover, sugarcane tcrps, etc.) without supplementation except table andlor<br />

mineral salts in some instances. With thls kind of feeding system,<br />

animals cannot be expected to perform well. However, many studies<br />

have shown that supplementation of feed with concentrates, andlor even<br />

urea-molasses-mineral block (UMMB) can improve the productivity of<br />

the buffalo (Leng, 1984; Leng, 1994; Neric et al., 1984; Abelilla and<br />

Oliveros, 1995).<br />

Genetic Improvement<br />

It has been demonstrated in Thailand that strict selection of<br />

breeding swamp buffalo bulls through performance testing greatly<br />

irnprwed their reproductive jmibmmce at the Surin Livestock Breeding<br />

Station. Konanta and Intaramongkol(1 W4) reported that the age of first<br />

calving of Thai bu&loes was reduced fim 5.26 + 0.94 years in 1976-77<br />

to 3.61 + 0.26 years in 1991, and calving interval, from 587.6 + 108.9<br />

days in 1981 to 493.7 + 100.1 days in 1991. Conception rate was<br />

inaeased fim 67.5% in 1 976-81 to 72.7% in 1 984-89, and calving rate<br />

from 66.6% in 1976 to 69.2% in 1989.<br />

Studies on crossbreeding of Murrah and swamp buffaloes<br />

showed sigdicant improvement in body weight and milk production as

Buffalo production systems in South East Asia<br />

well as the reproductive performance of the I?, crossbreds over those of<br />

the swamp buffalo (Jainudeen, 1989; Yongzuo and Weirning, 1991 ;<br />

Sitamorang and Sitepu, 1991 ; Ly, 1994; Momongan et al., 1994). The<br />

use of oestrus synchronization as a tool for the application of artificial<br />

insemination (AI) under village conditions has made possible the rapid<br />

production of Murrah-swamp crossbreds in the Philippines.<br />

The development ufbiotechnology is a potential tool for the rapid<br />

genetic improvement in water buffalo. Superovulation of genetically<br />

superior heifersldams and transferring the recovered embryos to<br />

synchronized recipients may hasten genetic improvement through<br />

efficient progeny testing and shorten the generation interval. In vitro<br />

oocyte maturation (IVMJ and fertilization (TVF) could be utilized to<br />

mprimize the genetic potential of a high-prized female buffalo. After the<br />

anunal has passed its usefulness and has been slaughtered, its ovaries can<br />

be recovered and the oocytes collected for IVM, NF and in vitro culture<br />

(NC) until ready far transfer to recipients or can be cryopreserved for<br />

fhture transfers. Cloning of fertilized cells would fiuther increase beyond<br />

imagination, the multiplication of genetic materials.<br />

Care and Management<br />

The majority ofsmallholder fanners allow the calf to be with the<br />

dam until milk secretion has dried up, thus prolonging the recurrence of<br />

postpartum oestrus, resulting in extended service periods. Studies have<br />

shown that early weaaing or restricted suckling induced the dam to return<br />

to early postpartum oestrus (Jainudeen and Shdddin, 1984;<br />

Wongsrikeao et al., 1990; Nordln and Jainudeen, 1991). Data at the<br />

Philippine Carabao Research and Development Center (PCRDC,<br />

1981-92) indicated that calfmortality under village conditions was about<br />

25% in areas where regular deworming of calves was not practised and<br />

only 10% in areas where PCRDC administered regular deworming of<br />

calves every three months. El-Garhy et a1. (1991) observed that calf<br />

mortality is an indicator afthe level of management under which the herd<br />

is reared.

V. G. Momongan<br />

Very often, the low conception rate and poor calf crop could be<br />

traced to the lack of breeding bulls andlor AT services in the community.<br />

The situation is fiuther aggravated by the common practice of castrating<br />

the big and strong bulls used for draught purposes. A responsive<br />

extension network which may include education of the farmers on<br />

appropriate buffalo management practices and extensive health care and<br />

bull dispersaVAI services which should be anchored to farmers' organized<br />

groups or cooperatives have been shown to be effective in advanced<br />

countties.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

The author extends his profound gratitude to Dr. Annabelle S.<br />

Sarabia for the assistance in the preparation of this manuscript and to the<br />

Organizing Committee for the invitation given to him to participate in the<br />

1995 SARECMARESA Regional Symposium.<br />

References<br />

Abelilla, N.C. and Oliveros, B.A (1995) Performance of growing crossbred<br />

carabaos fed nce straw supplemented with concentrate and/or<br />

urea-molasses-mineral-block. Proceedings of 32nd PSAS Annual<br />

Convention, 26-27 October 1995, PICC, Metro Manila, Philippines. Vol.<br />

1, pp 261-272.<br />

Alviar, N.G. (1986) Socioeoonomics of swamp buffalo raising in the<br />

Phhppines. h. International Seminar on Prospects and Problems of Asian<br />

Buffalo Development, 10-11 Apd 1986, PCARRD, Los Bsflos, Laguna,<br />

Philippines.<br />

Bouahom, B. (1994) Buffalo improvement in Lao PDR In: Long-renn Generic<br />

Improvement of the Buffalo. Bunyavejchewin, P., Chantalakhma, C. and<br />

Sangdid, S., Eds. Buffalo and Beef Production Research and Development<br />

Center, Bangkok, Thailand. pp 85-88.

Buffalo production systems in South East Asia<br />

Bunyavejchewin, P., Sangdid, S. and Chantalakhana, C. (1 994) Socio-economic<br />

conditions eecting the use of draught buffalo versus two-wheeled tractor<br />

in some villages of Surin province. In: Long-term Genetic Improvement of<br />

the Buffalo. Bunyavejchewin, P., Chantalakhana, C. and Sangdid, S., Eds.<br />

Buffalo and Beef Production Research and Development Center, Bangkok,<br />

Thailand pp 28-41.<br />

Calub, AD., CastiUo, L.S., Madamba, J.C. and Palo, L.P. (1971) The carcass<br />

quality of carabaos and cattle fattened in feedlot. Phil. J. Anim. Sci. 89,<br />

69-78.<br />

Chantalakhana, C. and Bunyavejchewin, P. (1989) Buffalo production<br />

research and development in Thailand In: Seminar on Buffalo Genorypes<br />

for Small Farms in Asia. Viadaran, M.K., Anni, T.I. & Basrur, P.K., Eds.<br />

Center for Tropical Animal Production and Disease Studies: Serdang,<br />

Malaysir pp 1 17-125.<br />

Cho, T.L.K. (1981) Buffalo production and development in Brunei. In: Recent .<br />

Advances in BufJalo Research and Development. FFTC Book Series No.<br />

22. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center. Taipei, Taiwan. pp 46.56.<br />

Cuong, L.X and Hien, N.X. (1989) Buffalo production in Vietnam. . In:<br />

Seminar on Bufnlo Geno* for Small Farms in Asia. Vidyadaran, M.K.,<br />

APni, T.I. and Basrur, P.K., Eds. Center for Tropical Animal Production<br />

and Disease Studies, Serdang, Malaysia. pp 153-1 58.<br />

De Guzman, Jr., M.R and Perez, Jr., C.B. (1981) Feeding and management<br />

practices, physical characteristics and uses of carabaos (swamp bufffaloes)<br />

in the Philippines. In: Recent Advances in Buflalo Research and<br />

Development. FFTC Book Series No. 22. Food and Fertilizer Technology<br />

Center. Taipei, Taiwan. pp 104- 1 15.<br />

El-Garhy, M.M., Metias, K.M., El-Rashidy, kk, Kholeaf, Z.M. and Tawfik,<br />

MS. (1991) A study on losses among newly born buffalo calves in a large<br />

dairy herd in Egypt. Thind World Buflab Congress, 13-18 May 1991,<br />

Varna, Bulgaria VoL IV, pp 1049-1054.<br />

Iban-a, P.I. (1988) Buffalo meat: Quantitative and qualitative aspects. Second<br />

World Buflalo Congress, 12- 16 December 1988, New Delhi, India. Vol. 11,<br />

Part 11, pp 514-523.<br />

Jainudeen, M.R (1 989) Buffalo fanning in Malaysia: A country report. In:<br />

Seminar on Buflalo Genorvpes for Small Farms in Asia. Vidyadaran, UK.,<br />

Azmi, T.I. and Basrur, P.K., Eds. Center for Tropical Animal Production<br />

and Disease Studies, Serdang, Malaysia. pp 145- 15 1.

V.G. Momongan<br />

Jainudeen, MR and Sharifuddin, W. (1984) Postpartum anoestrus in the<br />

suckled swamp buffalo. In: The Use of Nuclear Techniques to Improve<br />

Domestic Buflalo Production in Asia. International Atomic Energy Agency,<br />

Vienna pp 29-41.<br />

Joshi, D.C. (1988) Meat production in buffaloes. Second World BufSalo<br />

Congress, 12-16 December 1988, New Delhi, India Vol. 11, Part 11, pp<br />

491-498.<br />

Konanta, S. and Intaramongkol J. (1994) Buffalo selection schemes in<br />

Thailand. In: Long-term Genetic Improvement of the BufSalo.<br />

Bunyavejchewin, P., Chantalakhana, C. and Sangdid, S., Eds. Buffalo and<br />

Beef Produdon Research and Development Center, Bangkok, Thailand. pp<br />

71-84.<br />

Leng, R (1984) The potential of solidified molasses-based blocks for the<br />

cmmction of multinutritional deficiencies in buffaloes and other ruminants<br />

fed low-quality ago-industrial byproducts. In: The Use of Nuclear<br />

Techniques to Imp- Domestic Buflalo Production in Asia. International<br />

Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna pp 135- 150.<br />

Leng, R (1994) Nutritional strategies applicable in small farm enterprises to<br />

increase buffalo production. Proceedings of the First Asian BufSalo<br />

Association Congress, 17-21 January 1994, Khon Kaen, Thailand. pp<br />

29-38.<br />

Ly, L.V. (1994) Buffalo research and production development in Vietnam.<br />

Proceedings of the First Asian Buffalo Association Congress, 17-21<br />

January 1994, Khon Kaen, Thailand. pp 90-97.<br />

Momongan, V.G. (1992) Carabao draught power. In: Carabao Production in<br />

the Philippines. Ranjhan, S.K. and Faylon, P.S., Eds. PHY861005 Field<br />

Document No. 13. Book Series No. 12611992. Los Bailos, Laguna. pp<br />

165-182.<br />

Momongan, V.G., Parker, B.k and Sarabia, AS. (1994) Crossbreeding of<br />

buffaloes in the Philippines. In: Long-tenn Genetic Improvement of the<br />

Buffalo. Bunyavejchewin, P., Chantalakhana, C. and Sangdid, S., Eds.<br />

Buffalo and Beef Produotion Research and Development Centex, Bangkok,<br />

Thailand. pp 57-67.<br />

Neric, S.P., Aquino, D.L., Dela Cruz, P.C. and Ranjhan, S.K. (1984) Effect of<br />

urea-molasses-mineral block lick on the growth performance of caracows<br />

kept on themeda pasture of central Luzon during the wet season. In: The<br />

Use of Nuclear Techniques to Improve Damestic BufSalo Production in<br />

Asia. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna pp 127-133.

BufJh.10 production systems in South East Asia<br />

Nguyen, B.X, Ty, L.V., Duc., N.H. and Uoc, N.T. (1994) Biotechnology for<br />

buffalo genetic improvement in Vietnam. In. Long-term Genetic<br />

Improvement of the Buflalo. Bunyavejchepvin, P., Chantalakhana, C. and<br />

Smgdid, S., Eds. Buffalo and Beef Production Research and Development<br />

Center, Bangkok, Thailand pp 89-95.<br />

Nordin, Y. and Jainudeen, M.R (1991) Effect of suckling frequencies on<br />

postparhun reproductive performance of swamp buffaloes. Third World<br />

Buflalo Conps, 13-18 May 1991, Varna, Bulgaria. Vol. 111, pp 737-743.<br />

Oliveira, A de L., Veloso, L, and Schalch, E. (1991) Carcass characteristics<br />

and yield of zebu steers compared with buffalo. Third World BuSfalo<br />

Congress, 13- 18 May 199 1, Varna, Bulgaria. Vol IV, pp 10 19- 1026.<br />

Satan, G., Suradisastra, K., Lubis, A. and Nasir, C. (1994) The role of buffalo<br />

in Indonesia: Myth and reality. Proceedings of the First Asian Buflalo<br />

Association Congress, 17-21 January 1994, Khon Kaen, Thailand. pp<br />

285-293.<br />

Shrestha, N.P. and Parker, B.k (1994) Heterosis for growth and milk<br />

production in Phil-Murrah F, hybrids. Phil. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 20,26-32.<br />

Siturnorang, P. and Sitepu, P. (1991) Comparative growth performance, semen<br />

quality and draught capacity of the Indonesian swamp buffalo and its<br />

crosses In: Buffalo and Goats in Asia: Genehc Diversity and Its<br />

Application, 1@14 February 199 1. Tulloh, N.M., Ed. ACIAR Proceedings<br />

No. 34, pp 102-1 12.<br />

Toelihere, MR (1980) Buffalo production and development in Indonesia. In:<br />

BuffaIo Production for Small Fanns. Tetangco, M.H., Ed. FFTC Book<br />

Series No. 15. ASPAC Food and Fertilizer Technology Center: Taipei,<br />

Taiwan. pp 39-53.<br />

Wongmkeao, W., Boon-ek, L., Wanapat, M. and Taesakul, S. (1990) Influence<br />

of nutrition and sudhg patterns on the postpartum cyclic activity of swamp<br />

bu6kloes. In: Domestic BufSalo Production in Asia. International Atomic<br />

Energy Agency, Vienna pp 121-13 1.<br />

Yongzuo, X and Weiming, 2. (1991) Swamp buffaloes and their improving<br />

objectives in Sichuan of China. Third World Buffalo Congress, 13-18 May<br />

199 1, Varna, Bulgaria. Vol. 11, pp 355-366.<br />

Zava, M. (1991) Buffalo's meat production evaluation. Thld World BufSalo<br />

Cotzgress, 13-18May 1991,Varna,Bulgaria Vol. IV,pp 1011-1018.

SAREC/NARESA PROJECT ON DISSEMINATION OF<br />

INFORMATION ON IMPROVED B~WF'ALO<br />

PRODUCTION SYSTEMS TO SMALL FARMERS<br />

J. A de S. Siriwardene<br />

Project Coordinator<br />

SARECNARESA BufJaIo Information Dissemination Project<br />

Getambe, Peradeniya<br />

SRI LANK4<br />

The SARECJNARESA Buffalo Research and Development<br />

Programme initiated in 1983 was originally conceived as a research<br />

oriented project, based on the recommendations of the National<br />

Workshop held in 1980. However, at the end of the first two phases, the<br />

emphasis was changed fiom research to information dissemination.<br />

SAREC funding was provided initially for a period of five years fiom<br />

1 983 to 1989. The objectives of Phase I were to generate the baseline<br />

information on production systems and uses, and to identify the<br />

constraints to buffalo production in Sri Lanka. A Symposium was held<br />

at the end of 1989 to review the outcome of the research studies, and<br />

SAREC agreed to fund the research programme for a further 5 year<br />

period. During Phase I[, an interdisciplinary approach was introduced<br />

and studies were carried out on a wide range of subjects which included<br />

physiology and biochemistry, management and production, disease,<br />

reproduction and nutrition. In addition, it was also expected that the<br />

researchers would identify the major constraints that limited buffalo<br />

production and work towards the development of measures to overcome<br />

some of these constraints. It was also evident &om the surveys conducted<br />

that the buffalo still remained an important source of f m<br />

power<br />

associated with rice cultivation and that the animal was increasingly<br />

being used as a source of milk and meat. It was also evident that despite<br />

its low productivity, the animal will continue to play a vital role in the<br />

rural agricultural economy in the future.<br />

The research programme made outstanding contributions to<br />

knowledge, bringing about a greater understanding of the physiology,<br />